A Based Deal: The Chagos Agreement Is a Fourfold Win

On May 22, Mauritius and the U.K. signed an agreement that resolves their long-running dispute over sovereignty, rights, and security in the Chagos Archipelago. The agreement stipulates that the U.K. will recognize Mauritian sovereignty over the Indian Ocean island chain, and Mauritius will lease Diego Garcia—the archipelago’s largest island and home to a U.S. military base—back to the U.K, allowing the U.K. and the U.S. to continue operating their joint base there for at least another 99 years.

The agreement makes good on London’s promise that the deal would not undermine the long-term viability of the base on Diego Garcia. More than that, the treaty represents a just and pragmatic solution that lays the foundation for long-term U.S. basing with Mauritian assent. Once both sides ratify the agreement, possibly as soon as July when a British review period ends, the U.K. and the U.S. have an opportunity to build on the treaty’s momentum to deepen security and economic ties with Mauritius.

Background

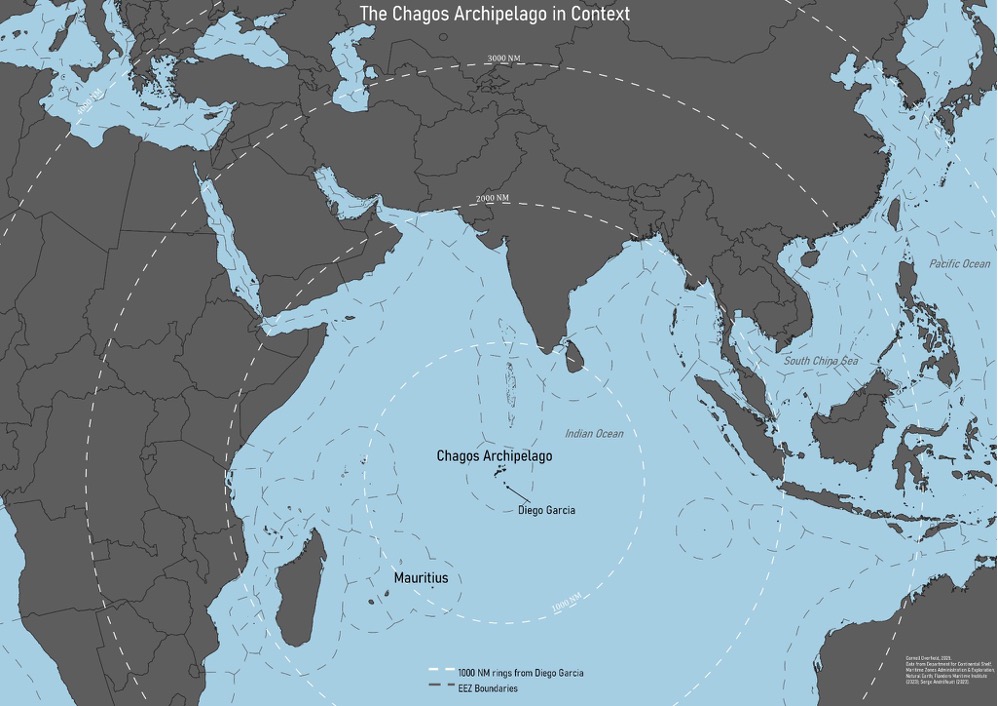

The Chagos Archipelago sits in the middle of the Indian Ocean, 1,000 miles southwest of Sri Lanka and 1,300 miles northeast of Mauritius (Figure 1). For the past 60 years, it has also sat at the heart of both U.K.-U.S. military posture in the Indian Ocean and a U.K.-Mauritius dispute over sovereignty. The U.K. conquered Mauritius from France during the Napoleonic Wars. For the next 150 years, from 1814 to 1965, the British government and the colonial administration consistently described the Chagos Archipelago as a dependency of Mauritius. In the early 1960s, the U.S. approached the U.K. about establishing military bases in the Chagos Archipelago. With Mauritius simultaneously pushing for independence, the U.K. decided that a secure U.S. base would require detaching the islands from Mauritius.

Figure 1. The Chagos Archipelago in Context. Prepared by Cornell Overfield.

Ahead of negotiations in 1965 with Mauritius’s premier (and future prime minister), Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson was briefed to “threaten [Ramgoolam] with hope”: the hope of independence and the threat that independence would be delayed if Mauritius clung to the Chagos Archipelago. Ramgoolam, later saying that “we had no choice,” bowed to the pressure and signed the Lancaster House Agreement. This detached the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius, paid Mauritius 3 million pounds in compensation, and declared that the islands “should be returned to Mauritius” [emphasis added] if they were not needed for defense needs in future. (In the 1970s, the U.K. returned several islands similarly detached from the Seychelles to that country when it realized they were not needed for defense needs.) With the Chagos Archipelago now part of the new British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), the U.K. prepared the territory for a U.S. base by clearing the islands of their inhabitants. By 1973, it had evicted all 1,500 Chagossians living on the islands, who tried to rebuild their lives in Mauritius, the Seychelles, or the U.K.

Since then, the joint U.K.-U.S. base on Diego Garcia has been strategically invaluable for military operations, logistical support, and intelligence collection throughout the Indian Ocean region. Starting in the 1980s, Mauritius mounted an escalating campaign in courts and international institutions to reassert sovereignty over the islands. Mauritius argued that the U.K. had violated international legal standards for decolonization forbidding pre-independence redrawing of colonial borders absent the “free and genuine expression” of popular will. Pressure for the U.K. to return Chagos increased sharply in 2019 after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) found in an advisory opinion that the U.K. violated international law by splitting the islands from Mauritius and had an obligation to complete decolonization. Around this time, Mauritius announced that it would offer the U.K. and the U.S. a 99-year lease to continue operating the base.

This solution, of U.K. recognition of Mauritian sovereignty and a long-term lease back to the U.K., raised several major security questions. Over 99 years, Mauritius, despite its strong security alignment with India, could end up developing closer ties to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). If so, might it authorize competing Chinese bases, allow PRC activity in or around the islands that enabled intelligence collection, or even rip up the lease? Even thornier questions remained: Would military operations be subject to Mauritian approval? And how would the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone apply to the U.K.-U.S. base?

At the same time, the status quo was increasingly untenable for American and British interests. For example, what if Mauritius simply approved Indian or PRC bases elsewhere in the archipelago on the basis of its widely-recognized sovereignty and dared the U.K. to stop them?

In 2022, Rishi Sunak’s Conservative government recognized that the U.K.’s position was eroding and entered into negotiations with the Mauritian government. Keir Starmer’s subsequent Labour government closed the initial deal in October 2024. President Trump’s election, however, and his administration’s hawkishness on China and suspicion of international law fueled fears (among deal advocates) and hope (among Conservative Party critics) that Trump would block the deal if given the chance. Still, instead of rushing ratification to present Trump with a fait accompli, Starmer offered the new administration a chance to review the deal already endorsed by the Biden team.

The Treaty Secures the Base

With the treaty in hand, it is easy to see why the Trump administration bought into the agreement. Its terms are explicit and detailed, and they put the base’s long-term future on clear and solid legal foundations.

On the island of Diego Garcia itself, the U.K. will be all but sovereign on defense and security issues for at least 99 years. Mauritius grants the U.K. a broad right to exercise all rights and authorities “required for effective long-term, secure, and effective operation of the Base” and recognizes its right to operate the base jointly with the United States (Article 2). U.K. and U.S. assets will enjoy unrestricted access, basing, and overflight (ABO), and the U.K. will have unrestricted ability to manage armed operations, access to the island, the electromagnetic spectrum, and non-U.K./U.S. military access to the base (Annex 1, Articles 1-3). These provisions legitimize and empower U.K. and U.S. military activities on the island. In another critical measure, the U.K. must merely “expeditiously inform” Mauritius when launching attacks on other states from Diego Garcia (Annex 1, Article 2). This preserves the U.K.’s and U.S.’s ability to plan, stage, and execute military operations from the atoll throughout the Indian Ocean region without Mauritian interference, influence, or veto.

Nuclear weapons are one point of partial ambiguity. The Treaty of Pelindaba establishing the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone prohibits deployment or basing of nuclear weapons in the zone but permits port visits at members’ discretion. Unrestricted ABO means that any temporary port calls by U.S. or U.K. vessels possibly carrying nuclear weapons should be acceptable under the treaty. The right to base nuclear weapons on the island is more ambiguous. On the one hand, the U.K. has an unrestricted right to manage “all goods, including … weapons” (Annex 1, Article 1(b)(ii)). On the other hand,the treaty defines “unrestricted” with a caveat that the U.K. and Mauritius may limit this with separate agreements “to meet the requirements of international or domestic Mauritian law” (Annex 1, Article 11). London, Port Louis, and Washington may already have an understanding on this, or it may be a matter for the Joint Commission, the U.K.-Mauritian arrangement’s management and dispute body, to hammer out if it becomes necessary.

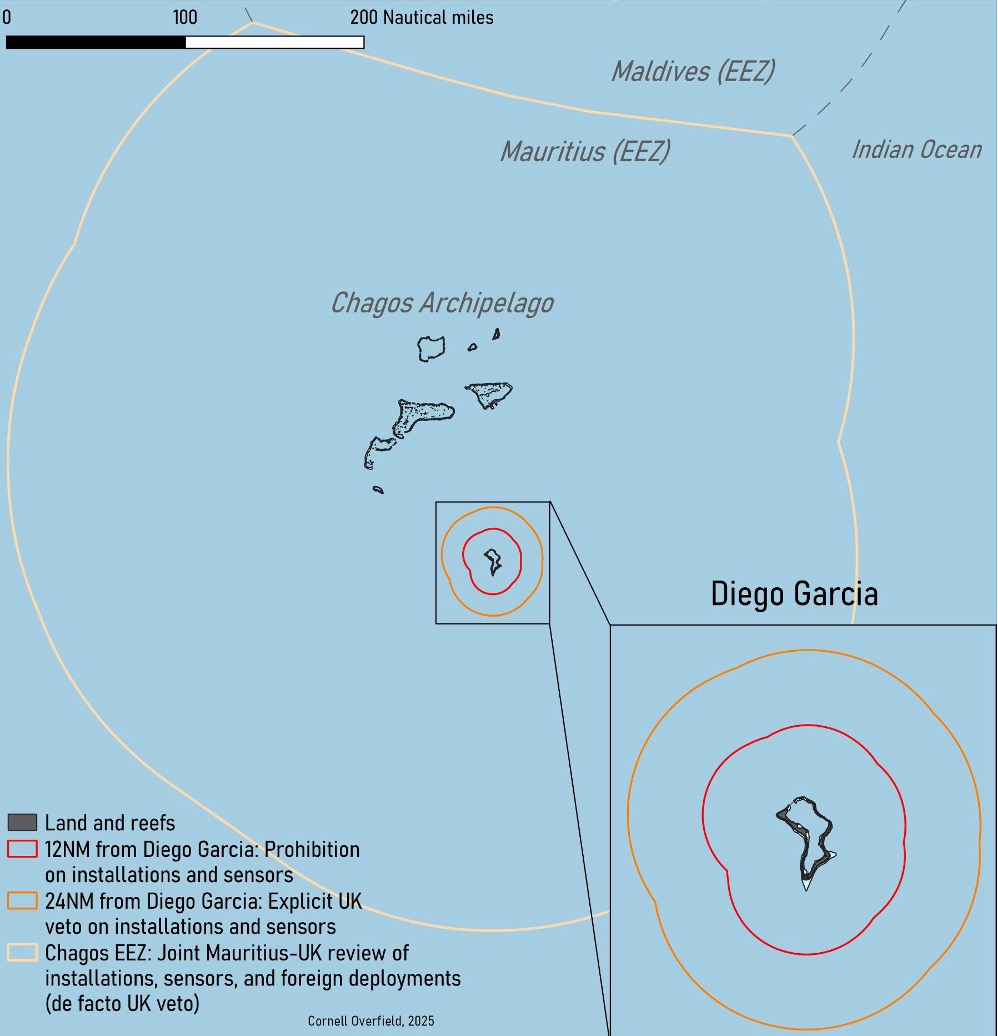

The treaty effectively provides the U.K. with a veto over any development on sea or land in the rest of the Chagos Archipelago. This generous veto power should ease concerns that Mauritius will simply allow the PRC to build an overt or covert presence to spy on the base. The U.K. can veto any maritime sensors or structure in the seas 12 to 24 nautical miles off Diego Garcia (Annex 1, Article 3(f)). Elsewhere in the archipelago, any maritime installations, sensors, structures, or artificial islands, and any development on land (including military bases), triggers a “security review.” The treaty spells out a process that starts with good-faith cooperation to mitigate possible security risks to Mauritian proposals but ultimately grants the U.K. an effective veto on physical infrastructure that it deems unacceptable (Annex 1, Articles 4-6). Mauritius can override U.K. objections only with a decision of the Joint Commission, where the two states have equal representation and all decisions require unanimity—the U.K. representative would simply not assent. The U.K. possesses a further veto on the presence of any non-Mauritian security forces, civilian or military, in the rest of the islands. Figure 2 depicts the geographic scope of these powers.

Figure 2. U.K. controls on developments in the Chagos Archipelago under the 2025 Chagos Agreement. Prepared by Cornell Overfield.

Skeptics of international law will worry that a future Mauritius working actively with China against U.K.-U.S. interests may simply ignore these provisions, but leaving the sovereignty dispute alive puts the U.S. and U.K. in a worse spot. Without a deal, the U.S. and U.K. would lack Mauritius’s public, legal commitment to joint decision-making with the U.K.. They would miss the opportunity to work collaboratively with Port Louis to head off a drift toward Beijing. Instead, they would leave an active sore in the relationship that could make Mauritius more willing to approve development and foreign basing that pose security risks to Diego Garcia. This approach might be more attractive to Port Louis if they believed that these approvals would reduce the base’s utility enough to drive out the U.K. and the U.S. It is far better for the U.S. and U.K. to take legal commitments and cooperative approaches than to insist on the uncertainties of contested sovereignty.

For critics worried about Mauritian treaty abrogation, the treaty provides the U.K. and the U.S. with significant protection from risks that future Mauritian governments could cancel the lease early. Under Article 15, Mauritius can terminate the treaty under only two conditions: the U.K. failing to pay its lease, or direct armed attack on Mauritius by the U.K. or forces stationed on Diego Garcia. If the U.K. does not accept the Mauritian termination, it can institute arbitration in front of an ad-hoc, balanced five-member tribunal that would issue a binding decision based on a majority vote.

Principal Critiques

Since the deal was announced, criticism has consolidated around three perceived flaws in the agreement: its surrender of British “sovereignty,” its financial cost, and its failure to achieve full justice for Chagossians. Of the three, only the last is a true flaw, but whether it is fatal is hard to assess as an outsider. The Conservative Party in particular is, as of June 2025, using all three critiques in a final effort to derail the deal in the British legislative branch. However, Conservative complaints that the deal is “bad for British taxpayers and bad for the Chagossian people” gloss over the inconvenient bind that a better deal for the Chagossian people would involve greater financial or security costs for Britain, while a “better” deal for British taxpayers or sovereignty would erase gains for Chagossians.

The enduring British critique of any negotiation over Chagos has been that Britain, as a sovereign state, need not surrender territory based on a mere advisory opinion. Doing so would conjure international law where none existed, and would encourage Spanish and Argentinian challenges to British sovereignty over Gibraltar and the Falklands. (Governments in Gibraltar, the Falklands, and the U.K. have consistently rejected that slippery slope parallel since 2019.) Still, it was the Conservative Sunak government that acknowledged the U.K.’s collapsing Chagos claim and opened negotiations with Mauritius over sovereignty. That history makes the current Conservative indignation that Labour would deal away “sovereign” soil seem more political than principled. Given its legal wins, Mauritius was unlikely to ever accept a negotiated settlement that did not end with the U.K. recognizing Mauritian sovereignty. Instead of soft sell-outs, Labour’s agreements on Chagos and Gibraltar’s border regime should be seen as pragmatic solutions to long-running problems to put British strategic needs and livelihoods, respectively, on clear and stable legal footing.

Conservative politicians and British defense analysts have also questioned the financial cost to taxpayers. The argument tends to be that the U.K. is unnecessarily trading free sovereign control for a hefty annual lease that will eat at domestic or defense investment. Average annual payments of 101 million pounds (at 2025-2026 prices) are hefty, totalling a face value of over 9 billion pounds over 99 years. Labour and the Tories have offered different approaches to the “real” cost: Labour applies the U.K. government’s standard net present value methodology to reach a total expected cost of 3 billion pounds, while Tories recently have pegged costs at around 30 billion pounds due to inflation.

At least from a security standpoint, 100 million pounds per year for a strong guarantee of unrestricted access to Diego Garcia seems a bargain. Imagine a world where the U.K. clings to Chagos but Mauritius green-lights a foreign base that dramatically reduces the base’s utility and drives the U.K. and the U.S. out. What could the U.K. buy for 100 million pounds per year, or even 9 billion pounds, if it had the full deal’s face value on hand, to compensate for Diego Garcia’s immense value for logistics, force staging, and power projection. From a force projection standpoint alone, if they had the total lifetime payments in hand as a lump sum, the U.K. could buy another two Queen Elizabeth-class carriers and their air wings (about 7 billion pounds in 2019, or about 9.5 billion pounds at current prices). But those are not a perfect substitute for Diego Garcia. Carriers would be retired after roughly 40 years, would launch only relatively short-range fighter aircraft, and would require further expenditure to sustain a suitable escort fleet. By contrast, Diego Garcia promises a base for a range of long-range heavy bombers and support assets capable of reaching a wide arc of Eurasia, and 99 years of utility (assuming the U.S. and the U.K. can mitigate sea level rise).

Some Chagossians, particularly those in the U.K., and international human rights experts have also condemned the deal for sidelining Chagossians and failing to ensure their right to return to Diego Garcia. U.K.-based Chagossians have been particularly critical of the deal, arguing that they did not have a seat at negotiations and want to remain part of the United Kingdom. In late May 2025, these groups filed an unsuccessful last-ditch legal challenge at the British High Court. Since October 2024, four independent experts affiliated with the United Nations have urged the U.K. and Mauritius to negotiate a new deal that better respects Chagossians and guarantees their right to return to all islands in the archipelago by closing the U.K.-U.S. base.

However, Mauritian sources point out that interests have diverged sharply between U.K. Chagossians, who focus on resettlement to Chagos, and their compatriots in Mauritius and the Seychelles concerned with both sovereignty and resettlement. Mauritian government representatives argue that sovereignty negotiations are rightfully a state-to-state matter but that they have always consulted Chagossians. Philippe Sands, Mauritius’s lawyer in the ICJ case, reports that Chagossians from Mauritius and Seychelles were “deeply involved” through consultations with the Mauritian government and that most, including leading Chagossian advocates such as Olivier Bancoult, support the deal.

The Diego Garcia exception to Chagossians’ right of return is a major gap in the agreement’s justice but one that some Chagossians are willing to accept and build from. This critique is ultimately one that is impossible to evaluate as a non-Chagossian: Is it better to hold out for a perfect agreement in the name of justice or accept a good-enough solution today that achieves most of the Chagossian movement’s goals?

If Mauritius and the U.K. push ahead with this “good-enough” agreement, the U.K. and the U.S. could continue to make amends to Chagossians by allowing them some access to Diego Garcia via contracts to Chagossian-Mauritian providers for base services. Mauritian Chagossians have already highlighted this possibility.

The Future of the Chagos Agreement

Ratification seems a sure thing in Mauritius. In the U.K., the Starmer government has agreed to ratify the agreement only after Parliament passes any required legislation. While the U.K.’s Conservative Party continues to decry the deal, Labour’s substantial majority should ensure smooth sailing. .

The treaty provides the U.K. and the U.S. with significant insulation from Mauritian political winds, but London and Washington would be mistaken to ignore Port Louis after the deal comes into effect. Mauritius’s approach to Chagos over the past decade indicates its good-faith willingness to partner with the U.K. and the U.S. on security issues. Ratification should not be the end of this cooperative approach, but a springboard for deepening relations in support of comprehensive security.

A closer economic and security relationship with Mauritius will make for a stronger deal and advance U.K. and U.S. security interests in the Indian Ocean. The deal’s economic windfall, which Mauritius is translating into debt payments and tax breaks, should entrench long-term Mauritian political support for the deal. Contracting with Mauritian (ideally Chagossian) providers for base services will further buttress Mauritian buy-in to the base and could provide an avenue to further justice for Chagossians. Finally, targeted security cooperation, particularly in the maritime domain, could allow Mauritius to contribute to securing the broader Chagos Archipelago. The Mauritian Coast Guard will likely require additional assets, training, and infrastructure to adequately patrol the Chagos Archipelago. This cooperative relationship with Mauritius should smooth U.K. and U.S. efforts to scrutinize and block developments in Chagos that threaten the base’s future security.

Mauritian and British negotiators delivered a treaty that is a win for Mauritius, a win for Chagossians, a win for the U.K. and the U.S., and a win for international law. Mauritius accomplishes its long-held objective of undisputed sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago and puts a price tag on Diego Garcia’s extreme strategic value. Chagossians will be able to return to most of the archipelago, and the U.K. and the U.S. could allow limited return to Diego Garcia as well. The U.K. remains all but sovereign over Diego Garcia itself, can continue allowing U.S. operations there, has a veto over developments or projects in the rest of the archipelago, and control the objective criteria that would allow Mauritius to terminate the agreement early. International law gets a much needed double boost given the role international law and institutions played in driving the U.K. to the table and the fact that the dispute was solved through negotiations and a robust, long-term treaty rather than force. This and future U.S. administrations can best make good the deal’s long-term promise by promoting international law (such as this treaty) as the basis for international relations and approaching Mauritius as a partner in regional security.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d27bd863_5)