Assessing Impacts of AI on Human Rights: It’s Not Solely About Privacy and Nondiscrimination

Artificial intelligence can significantly impact human rights—both positively and negatively. Human rights impact assessments conceived specifically for AI are needed to prevent potential harms and reap the benefits of the technology.

That artificial intelligence (AI) systems impact privacy rights has become a kind of truism, often met with a subtle eye roll or a repressed sigh.

The similar concerns about AI and discrimination have not quite become a truism just yet, but they are well on the way. Before long, these risks will have been hammered home often enough that they too will be commonplace.

Privacy and discrimination concerns have become key, almost reflexive, considerations for players in the AI field. But these accomplishments in addressing privacy and discrimination concerns are not the end goal. They are, rather, mere milestones on the road to the end goal, which is a broader consideration of AI systems’ impacts on human rights more generally.

The right to privacy and the freedom from discrimination are, after all, not the only fundamental rights potentially affected by algorithmic systems. AI systems also raise issues regarding the freedom of expression and the freedom of association, for example.

The most striking examples of this probably come from China, where the regime uses AI to censor speech related to anti-lockdown protests, among other things. But to be clear, infringements on privacy and discrimination also occur here in the Western world.

In order to move forward with AI and truly take advantage of its benefits, policymakers need to consider the impacts of these technologies on the whole range of fundamental rights and freedoms protected by human rights instruments such as:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- The International Covenants

- The U.S Bill of Rights

- The European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights

On Oct. 4, 2022, the White House took a step in the right direction, with its announcement of the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights (AIBoR). The AIBoR is not binding; it does not create any legal right for anyone. Rather, it’s a white paper that lays down President Biden’s vision of what the American approach to AI should be. It shows that the White House is interested in tackling a broader set of issues than just privacy and anti-discrimination.

The AIBoR also addresses two other human rights principles: the right to be protected from unsafe or ineffective AI systems and the right to receive notice and explanation of algorithmic decisions impacting individuals’ lives.

The “unsafe or ineffective systems” principle aims to protect people from AI systems that pose a risk to their security. For example, AI systems used to predict the onset of sepsis have caused trouble in health care systems by generating a concerning number of false positives. AI devices can also be used to help stalkers engage in harassment and abuse. Notably, this principle is closely related to the right to life and the right to security of the person guaranteed by Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The goal of the “notice and explanation principle” is to ensure that people affected by automated decisions receive clear and valid explanations so that they might understand exactly how they were impacted and whether to contest the automated decisions via an appeal process. This principle is closely related to the right to due process protected by the U.S. Constitution.

Abroad, the European Union is also moving forward with legislation that recognizes the importance of human rights in the context of AI. The proposed AI Act, for instance, promises to “enhance and promote the protection” of nine rights guaranteed by the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights. And the Digital Services Act introduces safeguards that also enhance the protection of a number of fundamental rights, including freedom of expression and information, freedom to conduct a business, and the right to nondiscrimination.

While it is good that AI regulators are beginning to broaden their horizons and starting to consider rights beyond privacy and anti-discrimination principles, these commitments are unlikely to make a difference without standardized processes to meaningfully assess how AI impacts individuals’ human rights and how to mitigate these impacts when they pose harm.

How Does AI impact Human Rights?

It is not always easy to imagine all angles of how AI impacts human rights. People often focus on privacy and anti-discrimination because potential issues that may arise in this regard are relatively easy to imagine. When it comes to other rights, however, the specific manner in which infringements materialize can be harder to conceptualize.

Freedom of opinion and freedom of expression are protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In the United States, these rights are protected by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Freedom of expression and accompanying freedoms associated with information protect people’s right to think and express what they want, and also protect the right to listen to the ideas and opinions of others.

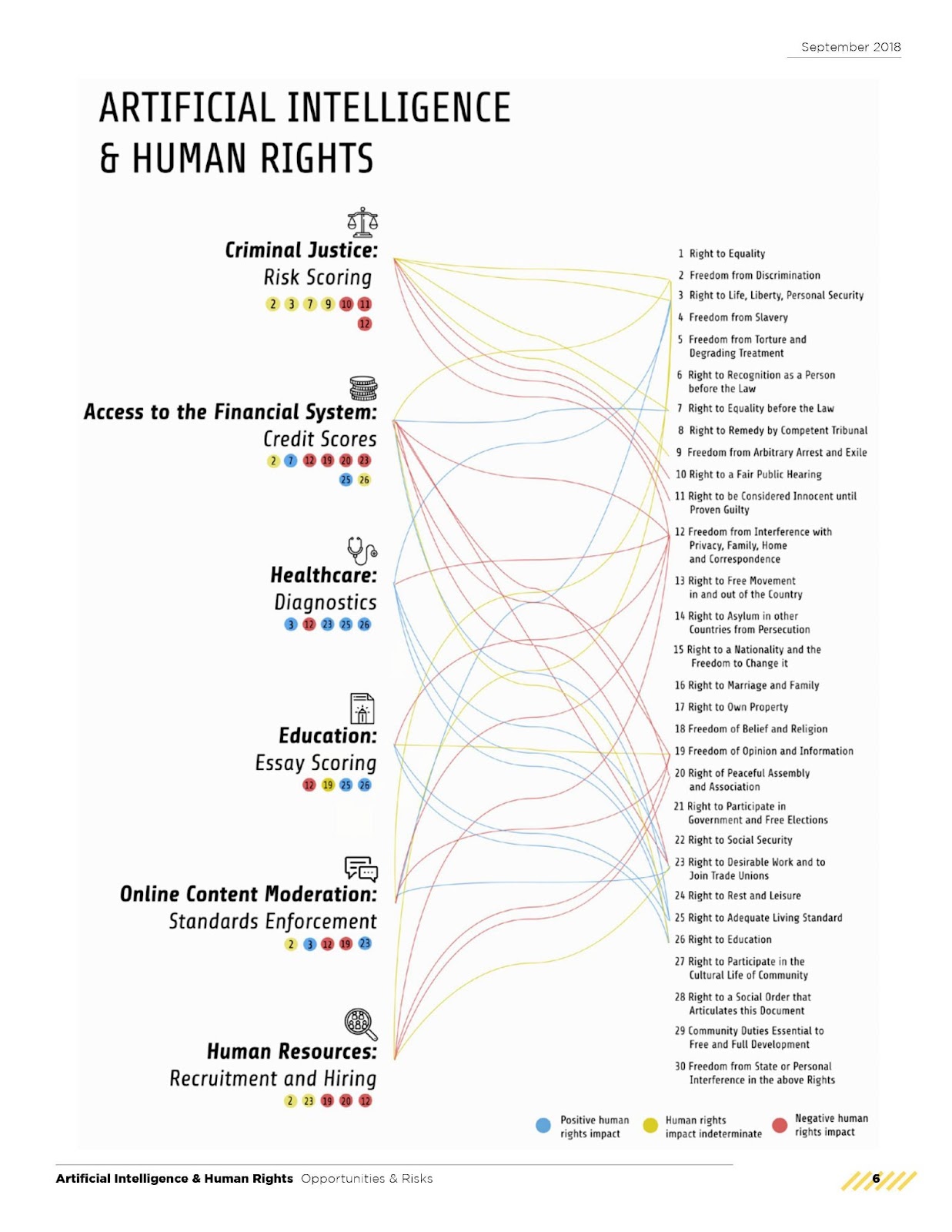

These fundamental freedoms are among those on which AI is likely to have the most significant impact. In the figure below, produced by the Berkman Klein Center, many red lines—which designate a negative impact on human rights—lead toward Article 19, which guarantees freedom of expression and freedom of opinion.

One of these red lines comes from content moderation algorithms—AI systems that go through content shared on social media and determine which publications should be taken down. These systems are likely to have a negative impact on freedom of expression because they may erroneously take down certain forms of legal and legitimate expression more frequently than human content moderators might.

And the difference is not insignificant.

During the coronavirus pandemic, for example, YouTube replaced many of its human content moderators with AI algorithms that were tasked with spotting and removing videos containing misinformation and hate speech. The platform’s content moderation experiment failed. AI systems over-censored users, doubling the rate of incorrect content takedowns. After a few months, YouTube rehired some of its human moderators.

Hiring algorithms—algorithms used by employers to screen candidates—offer another example of AI systems that might have a negative impact on freedom of expression.

These algorithms—for which “all data is hiring data”—are likely to encourage people on the job market to censor themselves to polish their online identity so that they are more appealing to potential employers. The amount of data that is taken into account by the hiring algorithms gives a new dimension to the self-censorship phenomenon. For example, a few ill-advised “likes” on Facebook can hurt a candidate’s chances of getting a job.

Good Egg’s AI system illustrates this strikingly. Good Egg is a company that sells AI solutions aimed at human resources managers. These solutions are marketed as social media background checks that analyze candidates’ online activities to determine if they might be troublesome employees. Good Egg searches for “risk factors” associated with a candidate, including slurs, obscene language, racy images, content that relates to drugs, and content that discusses self-harm. While the company doesn’t provide specific examples of what it considers to be obscene language or racy pictures, one can imagine that someone cursing on Twitter or posting flirtatious photos on Instagram would likely be penalized by the algorithm.

But don’t worry. The company assures its users that it is on the lookout for any potential infringement on the right to privacy, writing, “[W]e keep the concept of ‘Big Brother’ in check so you (and your future and/or current employees) can rest easy.” We rest assured.

Actually, we don’t.

This use of sarcasm is another expression that artificial intelligence systems struggle to grasp. Most often, AI systems experience difficulty capturing and understanding humor and irony, which exacerbates the negative impacts AI systems have on freedom of expression in terms of content moderation as well as in the hiring process.

For example, Kate Klonick, a leading expert on content moderation, was once banned from Twitter for posting a tweet containing the phrase “I will kill you”—which was considered an incitement to violence by Twitter’s algorithm. But Klonick wasn’t inciting violence at all. She was simply quoting a comical interaction between Molly Jong-Fast and her husband, who was about to take food away from her.

In another instance of algorithmic failure to understand humor, an AI system similar to that of Good Egg flagged an employee for sexism and bigotry because she “liked” a publication containing the colloquial expression “big dick energy,” a term used to describe people who are self-confident without being arrogant. Supreme Court Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, or Angela Merkel, for instance, have all been described as wielding “big dick energy.”

In addition to freedom of expression, at least two other fundamental freedoms risk being significantly affected by AI. Referring back to the Berkman Klein Center’s diagram, there are several red lines that point toward Article 20 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This provision protects the freedom of peaceful assembly and association—that is, the freedom to choose to associate with a group, or to disassociate from the group, as well as the freedom to participate in a peaceful demonstration.

Infringements on these freedoms—which are also protected by the U.S. Constitution and the EU Charter of Human Rights—may present in similar fashion as those relating to freedom of expression.

Indeed, not only can hiring algorithms encourage workers to refrain from expressing themselves online so that they do not potentially harm their job prospects, but they may also encourage workers to refrain from associating with certain groups out of fear of harming their careers. Many young people, for example, don’t feel comfortable sharing pictures that they may have taken during protests on Instagram, because they worry that it might affect future job opportunities. Even if a person refrains from sharing photos online, their mere presence—among others with phones and cameras—at the protest could pose a threat to potential job opportunities. What if these same students appeared in a picture somebody else posted online of the protest? Can a hiring algorithm still trace it back to them? Attending protests and associating with specific groups, regardless of personal behavior online, might still pose a threat to obtaining potential job opportunities. Because of this possibility, these young people are forced to think: “Maybe it’s safer to stay at home, far away from cameras.”

This is how AI can subtly erode freedom of association.

Navigate360 (formerly known as Sentinel) is another striking example of the potential impact of AI on freedom of association. It’s an AI system that scans social media and geolocation data to produce reports on topics such as potential threats of violence or suicide to help U.S. colleges keep their campuses safe. Although Navigate360 denies it, an investigation conducted by the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network revealed that the company boasted in promotional materials and emails that its technology is used by several university administrations to “forestall potential volatile protests/demonstrations.”

Additionally, reports generated by Navigate360 enabled university administrations to put surveillance measures in place to regulate protests about abortion and the “Muslim ban,” for example. On a more local level, students who had spoken critically of the University of North Carolina A&T’s administration were subjected to surveillance, also thanks to Navigate360.

What About Positive Impacts?

With all these possible AI-powered infringements on human rights, one might be tempted to adopt a general anti-AI posture. But that would be a mistake. These technologies have enormous potential, including potential to expand human rights.

Health Care

AI could, for example, have positive impacts on the right to life and personal security protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as on the right to health guaranteed by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. AI skeptics tend to skip over the numerous examples of how AI can help promote these rights. But when assessing the impact of a technology on human rights, observers cannot ignore the benefits the technology offers. And it’s not all just chatting with ChatGPT or creating doodles with Dall-E.

For instance, AI promises to provide the “gift of time” to overwhelmed health care practitioners—freeing them from certain time-consuming tasks such as resource allocation, appointment scheduling, and notetaking to allow them to spend more time with patients and provide better care overall. With AI’s assistance, physicians could spend more time listening to their patients and creating genuine connections.

AI systems could also contribute to a reduction in medical errors—a real issue in many health care systems—and improve medical diagnostics performance as well as resource allocation in health care institutions like hospitals. For example, AI could be used to optimize antimicrobial prescriptions—in other words, to provide the right dose at the right time for the right amount of time—or to identify patients at risk of nosocomial infections in real time in order to manage the infection quickly and prevent further contamination.

AI could also speed up the drug development process. As established with vaccine development and manufacturing during the coronavirus pandemic, a quick drug development process is critical in times of crises. But speedy drug development can also be life saving in non-pandemic times. For instance, AI systems are used to find treatments for cancer, diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, among other life-threatening illnesses.

Education

AI could have positive impacts on the right to education. Translation tools powered by AI systems, for example, could allow students to benefit from content they would otherwise not have had access to because of language barriers.

However, one must be cautious when pondering the hypothetical gains of AI. In a recent report, the Council of Europe pointed out that general discourse about the use of AI in education is most often enthusiastic but is notably marked by a tendency to inflate beneficial effects.

This phenomenon, of course, is true of the discourse about risks too. The digital environment is not some sort of technological utopia, but society is not on the verge of an AI apocalypse either.

Content Moderation

Some of the AI systems discussed previously for their negative impacts could also have positive impacts on human rights.

Consider content moderation algorithms once again.

Working as a content moderator is an extremely taxing position. It is common for content moderators to develop anxiety problems or post-traumatic stress disorder because their jobs require viewing images of murders or sexual abuse of children, among other horrifying events. The use of content moderation algorithms to limit moderators’' interactions with particularly traumatic content could have positive impacts on the right to fair and reasonable working conditions that respect the health, safety, and physical integrity of the worker—a right guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Approaches to the Human Rights Impact Assessment

Currently, there is no standardized process for measuring the impact of AI systems on human rights. A promising approach to address these issues is the use of AI human rights impact assessments (HRIAs). Notably, a number of prominent voices are already encouraging the development of such tools, including the Carr Center, Access Now, and Data & Society, as well as the ad hoc committee on artificial intelligence (CAHAI) of the Council of Europe.

An HRIA is similar to an environmental impact statement. It’s a process that examines the implications of certain projects while it’s still possible to modify—or even abandon—them. In the same way that environmental impact statements help policymakers gauge the impact of potential projects on the environment, an HRIA could help AI developers and deployers (such as government agencies or businesses) anticipate and mitigate the impacts of AI systems on human rights before and after the systems are available to the general public.

Unlike environmental impact statements, HRIAs are still fairly new. Interest in them first arose around 2011 when the U.N. Human Rights Council endorsed the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which required that businesses carry out due diligence to ensure that they are not infringing on human rights. In response, HRIAs became a way to operationalize this new obligation. But assessing human rights impacts of AI systems is quite different from assessing the human rights impacts of, say, a fast fashion company. Thus traditional HRIAs are ill suited for the tech industry.

In 2018, for example, Facebook commissioned a consulting firm to carry out an HRIA about the alleged human rights harms it caused in Myanmar. The results were disappointing. While it did look into content moderation policies, the HRIA failed to assess the impacts of Facebook’s news feed algorithm on the wave of violence faced by Rohingya Muslims, a minority group that faced murderous repression in the country. The firm’s failure to examine technical factors’ role in human rights violations is one of the main reasons why Facebook’s HRIA was considered a failure among the academic community.

Learning from this example, those who advocate for HRIAs on algorithms now argue that processes that are designed specifically for the field of AI are needed for the HRIA to be effective. HRIAs for AI must examine the inner workings of algorithms—in other words, they have to scrutinize their specific technical components. HRIAs for algorithms also must be conducted throughout the whole life cycle of an AI system—beginning from the early days of its conception, to key moments during the development of the system, as well as punctually after its implementation. They shouldn’t be merely ex ante or ex post endeavors. Newly emerged HRIAs that fit these criteria include the Fundamental Rights and Algorithm Impact Assessment—which was developed by the government of the Netherlands—as well as the Human Rights, Ethical and Social Impact Assessment in AI—which was developed by Alessandro Manterelo at the University of Turin. Both HRIAs provide guidance to help AI developers identify their systems’ impacts on a wide array of fundamental rights. They also offer several examples of potential mitigating measures to avoid negative impacts. All of this reduces the risks of unjustified infringements on human rights.

Supporting HRIAs Through Regulatory Means

American and European governments currently support the development of standardized algorithmic impact assessments. Overall, this is a good thing. Indeed, impact assessment processes work best when they are backed by global policy or legislation—think of the environmental impact assessments, for instance, for which success is intimately related to the enactment of the American National Environmental Policy Act.

The catch, though, is that these standards are unlikely to meaningfully address the broad range of human rights that the AIBoR, the AI Act, and the Digital Services Act all purport to tackle.

For example, take the Algorithmic Impact Assessment (AIA) released by the American federal chief information officer (CIO) in April 2022. The AIA aims to help “federal government agencies begin to assess risk associated with using automated decision systems.” But notably, no strong regulatory powers such as a law or an executive order mandate it.

Therefore, it’s not clear if any agency has actually used the AIA. At least, if one has used it, it didn’t publicly release the results.

Moreover, the way the AIA addresses human rights issues lacks sophistication. One of the (few) questions it includes regarding human rights reads as follows:

Please outline potential impacts or risks you are currently anticipating in regard to this project. (For example, privacy, civil rights, civil liberties.)

This kind of question doesn’t provide any helpful guidance to technologists who want to identify a system’s impacts on human rights and may lead to a performative assessment. As has been pointed out, though in another context, free-text questions like that can easily be answered with something akin to “my system has no possible negative impacts.”

This may be the reason why the CIO’s AIA has been described as a “useful start,” at best—because it’s “fairly basic.” But it’s only an alpha version. It can still be improved.

A good way to accomplish this goal would be to take inspiration from the Netherlands.

The Netherlands doesn’t have an impeccable track record when it comes to AI and human rights; the country is infamous for its use of a discriminatory algorithm that considered low-income families and parents with dual nationality more likely to commit tax fraud. As a result, several families—often immigrants—were falsely accused of child care benefits fraud. Following these false accusations, victims were left to suffer from mental health issues and children were wrongfully taken away from their families.

The Netherlands is now taking concrete steps to avoid other scandals like this.

In April 2022, the Dutch Parliament adopted a motion to mandate HRIAs for public institutions that use AI. The motion followed the release of a comprehensive HRIA that four scholars from the University of Utrecht developed for the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations.

The framework of the comprehensive HRIA considers how AI systems impact more than a hundred fundamental rights and sub-rights—freedom of expression is subdivided into many sub-rights, such as freedom of the press, academic freedom, and whistleblowing, for instance—and it also proposes a significant list of preventive and mitigating measures to limit infringements on these rights.

In addition, guidelines as to how to conduct an interdisciplinary dialogue and engage with affected communities are also included in the framework.

Taking inspiration from the Netherlands, the CIO could beef up the AIA to make it more comprehensive and more focused on human rights. For example, in line with the “unsafe or ineffective systems” principle from the AIBoR, questions about the accuracy of the algorithm could be added: how often is the AI system wrong, for instance. Additional questions regarding explainability would also be an improvement to the current AIA. Developers could be asked to justify why a black-box algorithm is needed instead of a less sophisticated algorithm that is more explainable.

Then, in compliance with Executive Order 13960 concerning the government’s use of trustworthy AI, federal agencies could be required to conduct this new impact assessment before developing, procuring, or implementing the use of any AI system, or at least any high-risk AI systems like algorithmic tools used in the judicial system to predict the likelihood of recidivism, for example. Such a requirement wouldn’t be unprecedented in the United States. The E-Government Act of 2002 already requires that agencies conduct a privacy impact assessment before:

(i) developing or procuring information technology that collects, maintains, or disseminates information that is in an identifiable form; or

(ii) initiating a new collection of information that—

(I) will be collected, maintained, or disseminated using information technology;

and

(II) includes any information in an identifiable form permitting the physical or online contacting of a specific individual, if identical questions have been posed to, or identical reporting requirements

This solution would be consistent with a proposal by the Electronic Privacy Information Center regarding potential ways to move forward with the AIBoR, and it would also address the concern highlighted by Brookings scholar Alex Engler regarding the White House’s failure to play a “central coordinating role” to help agencies move forward with the regulations.

As for the European Union, Brussels regulators could also also take inspiration from their Dutch neighbors (and constituents).

On Dec. 5, 2022, the European Commission released a draft standardization request asking that the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) and the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC) produce a series of 10 standards intended to support the development of safe and trustworthy AI in Europe. None of these 10 standards is specifically focused on human rights—and human rights probably won’t prove to be an underlying theme uniting them all either.

One key reason for this is that human rights experts will likely play only a secondary role in the development of these standards. The standards organizations tasked with their production are specialists of product safety regulation—not human rights. Despite not being well versed in human rights matters, they are not required to develop significant expertise in the domain. The standardization request merely requires that they “gather relevant expertise in the area of fundamental rights” while it sets a more onerous requirement for the implication of businesses: “effective participation of EU small and medium enterprises” must be ensured.

But the request released on Dec. 5 is only a draft. It can still be updated to include an additional impact assessment focused on human rights. This hypothetical HRIA might look like the Dutch one. Or it could look like Mantelero’s Human Rights, Ethical and Social Impact Assessment, described above, which is informed by the case law of various European data protection authorities.

To make HRIAs mandatory under the AI Act and the Digital Services Act, no major changes would be necessary. Brandie Nonnecke and Philip Dawson proposed concrete ways to accomplish this, including a revision of Article 9 of the AI Act “to make the assessment of AI systems’ human rights risks an explicit feature of high-risk providers’ risk management systems.”

This idea has been echoed by members of the European Parliament. Indeed, European Parliament co-rapporteurs Brando Benifei and Dragoş Tudorache circulated a new batch of amendments on Jan. 9. Under these new amendments, a fundamental rights impact assessment would be required for all users of high-risk AI systems. This would show that when it comes to AI, Europe takes its commitment to human rights seriously.

As for the Digital Services Act, Nonnecke and Dawson recommend that its Article 26—which requires that very large online platforms conduct risk assessments—be interpreted as connected to the obligation to conduct organization-wide human rights due diligence processes under international law. This is not a substantial change, merely a clarification. Indeed, Article 26 already requires that very large online providers assess their platforms’ impacts on many enumerated fundamental rights. All that would be needed is to unambiguously affirm that this provision flows from the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which is the document that gave rise to HRIAs’ popularity after being endorsed by the U.N. Human Rights Council.

Now, of course, all of this is easier said than done. A fair amount of work is still needed before HRIAs for AI are ready for prime time. Collaboration with academia, civil society, standardization bodies, and tech companies will be needed to define what HRIAs for AI should look like.

But this is the path forward.

This inclusion of human rights considerations in the AI Bill of Rights, the AI Act, and the Digital Services Act marks a significant milestone. Now, in order for it to be truly impactful, these commitments toward human rights must also reflect on the operational mechanisms that legislators are promoting. As for the next step? Policymakers and stakeholders must build a strong culture of human rights impact assessment for AI with government-supported processes that account for human rights—all of them, not only privacy and anti-discrimination.