Behind the Scenes of the Nixon Pardon

A review of Jeffrey Toobin, “The Pardon: The Politics of Presidential Mercy” (Simon & Schuster 2025)

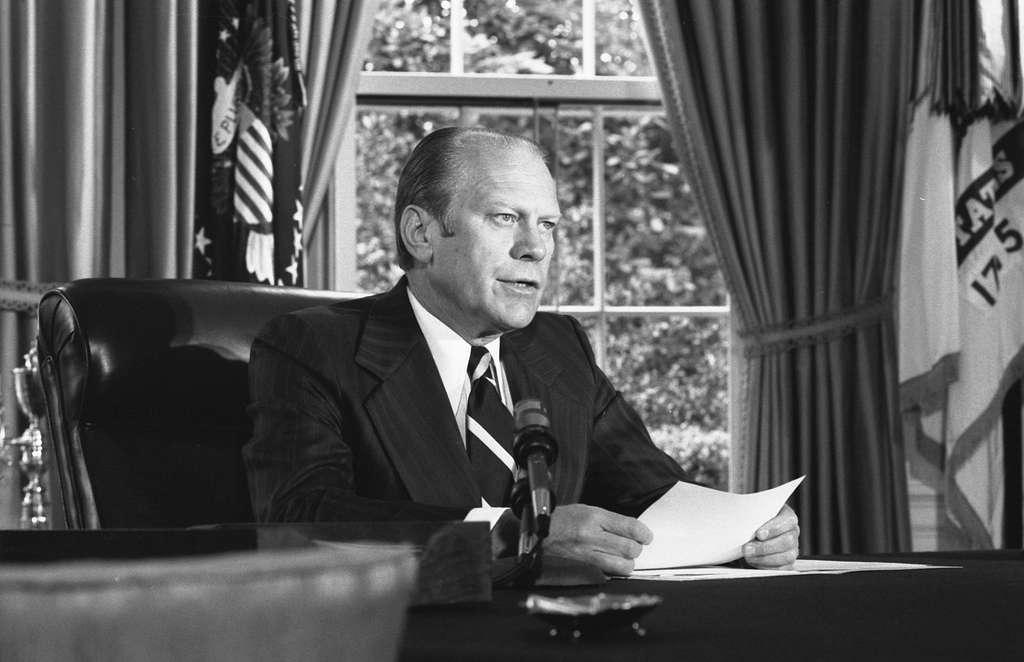

Jeffrey Toobin’s new book, “The Pardon: The Politics of Presidential Mercy,” offers a detailed look into the machinations preceding the most famous presidential pardon in U.S. history (unless President Trump’s recent mass pardons of Jan. 6 convicts eclipse it): President Gerald Ford’s pardoning of the disgraced Richard Nixon for crimes relating to the Watergate scandal. By Toobin’s reckoning, Ford’s decision to pardon Nixon was both contemptible and foolish, converting Ford into an unwitting “villain in the story” of the spectacular downfall of his former boss, who, by resigning the presidency on Aug. 8, 1974, catapulted Ford to power without Ford’s ever having appeared on a nationwide ballot. Ford had nothing to do with the Watergate break-in or the White House cover-up, yet the pardon defined his legacy. While Nixon got “a free pass, a total gift, a complete exoneration,” as Toobin sees it, Ford’s four years as president began—and ended—with the plague of Watergate, which many believe cost him a second term. (Toobin isn’t so sure.)

Toobin conducted dozens of interviews for the book, which opens with a narrative of how Ford got both top White House jobs. Nixon had chosen his first vice president, Spiro Agnew, as an “insurance policy” against impeachment and removal. After Agnew resigned on tax evasion charges, Nixon tapped the unassuming Ford to replace him, believing that he too was “a light-weight whom one could envision as President.” In an Oval Office conversation with Nelson Rockefeller (who was then the governor of New York and a contender for vice president), Toobin writes, “Nixon put his hands on the arms of his chair and said with contempt: ‘Can you imagine Jerry Ford sitting in this chair?’”

The book paints a picture of Ford as politically naive, despite his having served 24 years in Congress. Ford assumed the vice presidency in the midst of the Watergate investigations, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee while seeking confirmation for the vice presidency just days after the so-called Saturday Night Massacre—a series of resignations by Justice Department officials who refused to carry out Nixon’s order to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox.

Cox had drawn Nixon’s ire for refusing to drop a subpoena for the Oval Office tape recordings that wound up documenting the president’s involvement in the Watergate cover-up, including what was later deemed the “smoking gun” tape. On June 23, 1972, a week after five burglars broke into Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate Hotel complex in Washington, D.C., that tape recorded Nixon conspiring with his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, about a plan to use the CIA to get the FBI’s Watergate investigation shut down. Nixon directed Haldeman to say to the CIA: “You open the scab there’s a hell of a lot of things, and that we feel that it should be very detrimental to let this thing go any further.” “Play it tough,” he added. “That’s the way they play it, and that’s the way we are going to play it.”

In Toobin’s account, Vice President Ford insulated himself from anything related to Watergate on the misguided notion that it was politically prudent to stay out of it. Although Nixon was eventually impeached for obstructing justice and abusing his office, he was never tried by the Senate or criminally indicted by the special prosecutor’s office. Cox’s successor, Leon Jaworski, had no appetite for prosecuting a former president, although others on his team thought it imperative to hold Nixon accountable for what they believed were serious crimes.

Toobin describes the political and legal jousting—both within and outside the White House—around the public release of the tapes, which ended in a 9-0 Supreme Court ruling against Nixon, who resigned 16 days later. The opinion held that presidents do enjoy something called “executive privilege,” which can be invoked to withhold documents from the public in certain circumstances. The Court largely created the doctrine of executive privilege—or what has come to be known as the presidential communications privilege—based on the rationale that presidents must feel free to engage in confidential deliberations with advisers if they are to lead the nation effectively. But in Nixon’s case, it concluded, that privilege had to give way to the “fundamental demands of due process of law in the fair administration of criminal justice.”

Chastened by that ruling, and facing the possibility of indictment, Nixon wanted a pardon—and badly. He also endeavored to retain exclusive ownership of his presidential records, which at that point in history were considered the personal property of outgoing presidents. Nixon and his close advisers, including White House Counsel Fred Buzhardt and Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, toyed with various scenarios, including the idea of a self-pardon (which Nixon rejected), pardons for the cover-up defendants, and even a “presidency-for-pardon trade” with Ford. Nixon wanted no fingerprints on any negotiations, however. On Aug. 1, 1974, he sent Haig to tell Ford that he had “made up his mind to resign.” Toobin reports that Ford later told veteran journalist Bob Woodward that Haig actually “offered a straight-up trade,” which Ford refused.

Toobin describes the pre-pardon process as “a peculiar three-way negotiation between Jaworski, Ford’s lawyers, and Nixon’s lawyers that was, at its core, barely a negotiation at all. All three sides wanted the same thing—for Ford to pardon Nixon. The only question was how to get there in politically acceptable ways for all three parties.”

Ford ultimately pardoned Nixon because he believed, as Toobin puts it, that a pardon would offer “no free ride” for Nixon. He relied on the reasoning of a 1915 Supreme Court decision, Burdick v. United States, in which Justice Joseph McKenna had written for the Court that a pardon “carries an imputation of guilt; acceptance a confession of it.” These assertions have never carried the force of law, however, and, as a practical matter, are overstated. Presidents have pardoned people who were wrongly convicted after their deaths; posthumous pardons operate to declare the deceased innocent—not guilty. Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, which grants the presidential pardon power, says nothing about the matter.

Ford later dispatched a 36-year-old volunteer lawyer, Benton Becker, to broker the delicate pardon negotiations with Nixon, who by then was living in California. Toobin characterizes Benton as “someone whom history has largely forgotten.” He was a former trial attorney at the Department of Justice but held no official government role under Ford. Becker had been part of a prosecutorial team that investigated New York congressman Adam Clayton Powell for taking kickbacks from staff. Ford was on a congressional committee in connection with the probe, and the two “hit it off.” Writes Toobin: “Even after Ford became president, when the two men were alone, Becker called him ‘Jerry,’ not ‘Mr. President.’”

By the time Ford pulled him in as “one person whose loyalty was to Ford alone,” he had only recently been cleared of criminal charges involving one of his private clients. Toobin’s description of how Becker found Nixon (apparently based on Ford’s memoir, “A Time to Heal”) is jarring: “The former president was just sixty-one years old, but Becker thought he looked eighty-five. His head seemed huge, disproportionate to his body, and the famous jowls hung low from his face. His fingernails were yellowed, not because Nixon was a smoker—which he wasn’t—but as a symptom of general decline.”

Becker made sure that Nixon “heard the words about Burdick,” and left convinced that “Nixon’s acceptance of the pardon, plus his acknowledgment that ‘he had not acted ‘forthrightly,’ amounted to a confession to obstruction of justice.” Becker’s read on things turned out to be wrong. Nixon never accepted responsibility. Ford nonetheless pardoned him prematurely and awkwardly, asserting in his public statement that the story of “‘Richard Nixon, and his loyal wife and family ... is an American tragedy in which we have all played a part.’” Toobin calls this “an outrageous thing to say. Americans did not play a part in it.” Nixon was no victim.

For his part, Ford was “astonished, and horrified” by the negative backlash, going so far as to do “something extraordinary, even unprecedented” by agreeing to testify under oath before a congressional subcommittee about his decision to pardon Nixon. Toobin writes that “for the rest of his presidency, and indeed for the rest of his life, he sought to explain why he pardoned Nixon.”

According to Toobin, Ford justified his decision this way: “‘I wanted to do all I could to shift our attentions from the pursuit of a fallen President to the pursuit of the urgent needs of a rising nation.’” In other words, he didn’t want his presidency bogged down by the distractions of a former president’s prosecution. What he missed, Toobin points out, was that Jaworski would probably have declined to indict anyway. By pardoning Nixon, Ford achieved exactly what he was seeking to avoid.

For Gen X-ers and their parents, the Nixon presidency stands out as one of the most corrupt in modern history. In fluid and accessible prose, Toobin’s narratives, which were drawn from extensive new interviews, add flavor and nuance to the historical record of this momentous time in American history. But for younger generations who weren’t even born in 1972, and may have little memory of American politics before Donald Trump, the tale of the Nixon pardon may seem both obtuse and benign.

The real strength of the book does not lie in its somewhat familiar account of the Watergate era. It’s instead in the harsh ironies Toobin deftly outlines, the “thens” versus the “nows.” Back then, the beleaguered president understood that he could be held accountable for crimes in office and at least attempted to cover up his participation in unseemly activity. Back then, members of the Republican Party, cognizant of the public’s likely intolerance of Nixon’s abuses of his office, pushed him to resign. And back then, the Supreme Court unanimously held that the most closely held musings of a president—those that take place within the confines of the Oval Office itself—are not immune from criminal oversight. With the passage of the Presidential Records Act in 1978, a bipartisan Congress also made presidential records the property of the people as a matter of law, something that would be unthinkable in today’s polarized climate. (Toobin adds the little-known fact that in 2000, the federal government paid Nixon’s estate $18 million to reclaim his records for posterity.)

All of that was washed away with the Supreme Court’s 2024 ruling in Trump v. United States, in which the far-right majority greenlighted presidential crimes as above legal reproach so long as they are done using the massive official powers of the presidency. The majority’s suggestion that abuses of unofficial power are the real problem is, of course, preposterous. It is the abuse of official power that does serious damage to individual liberties and the constitutional order, not the unofficial stuff. Toobin thus aptly observes: “If that Supreme Court ruling had been in effect in 1974, Richard Nixon would not have needed a pardon. His conduct in supervising the Watergate cover-up would likely not only have been off-limits for prosecution.” Indeed, “[i]t would have been unlawful even for federal prosecutors to investigate it in the first place” because the Trump majority further held that prosecutors cannot “‘admit testimony or private records of the President or his advisors probing the official act itself.’”

Checkmate. Presidents thus became kings.

As Toobin repeatedly notes throughout the book, pardons are essentially political acts, not legal ones. “For better and worse,” he quips, “pardons operate like X-rays into the souls of presidents.” Pardons have an ancient lineage, predating even the New Testament account of Pontius Pilate’s refusal to grant one to Jesus. In common law England, from which the Constitution’s pardon power is derived, a primary purpose underlying the monarch’s granting of pardons was mercy. In England, criminal jury trials did not appear until the 12th century, and criminal punishments were harsh. Kings also used pardons to foster reconciliation after a national disturbance, which today is known as “amnesty.” And they used them as well for patronage and self-dealing.

To this day, pardons can be both compassionate and corrupt. Either way, the Constitution doesn’t seem to care—or at least that’s how the modern Supreme Court sees things, as made clear in its criminal immunity ruling, calling the pardon power “core” and thus above reproach, even if used to commit a crime.

Toobin’s book is part history, part biography, part law, and part editorial—offering important insights into the last time gross corruption infected the White House. By connecting the dots to the “now,” Toobin quietly plants Trump behind every page of this book. At its core, it seems, whether a pardon is good or bad comes down to the integrity of the president who wields it. (Toobin ticks through other modern presidents’ notable pardons, from Carter to Biden, noting that only Barack Obama seems to have had an impeccable record.) And although he does not come out and say it, Toobin’s book implies that integrity still should matter for presidents. “Gerald Ford revealed himself to be earnest, impatient, and overmatched by the dark genius of his predecessor,” Toobin concludes, while Trump’s [first term] pardons and commutations “were all, at their core, about Trump himself—deposits and withdrawals in his favor bank. They were tokens of gratitude, expressions of vengeance, payments for future consideration, and acts of political provocation.”

Billed as a general study of the politics of presidential mercy, “The Pardon” exudes nostalgia for a bygone era when presidential wrongdoing actually mattered, when at least some politicians put voters over party, and when Supreme Court justices cared about their oaths to uphold the Constitution. Because it comes on the heels of Joe Biden’s controversial “pre-pardons” of family members, and Trump’s mass endorsement via pardons of political violence at his behest, the book is at the same time outdated and tragically current. One is left to wonder how a retrospective like Toobin’s would unpack today’s unfettered conception of the presidential pardon power 50 years hence.