Bill Barr’s Very Strange Memo on Obstruction of Justice

The memo on obstruction of justice by Bill Barr, the once and future attorney general, is a bizarre document—particularly so for a man who would supervise the investigation it criticizes.

The memo on obstruction of justice by Bill Barr, the once and future attorney general, is a bizarre document—particularly so for a man who would supervise the investigation it criticizes.

As the Wall Street Journal first reported, Barr, whom the president has nominated to succeed Jeff Sessions as attorney general, sent the unsolicited memo—dated June 8, 2018—to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein to offer his view of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into possible obstruction of justice by the president. The document elicited questions over whether Barr would need to recuse himself from overseeing the investigation as attorney general, along with outrage from congressional Democrats: both Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sen. Mark Warner, the ranking member on the Senate intelligence committee, have demanded that Trump withdraw Barr’s nomination. Sen. Dianne Feinstein of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary described the memo as “troubling.”

But the legal quality of the memo itself is a different question. Over at Just Security, Marty Lederman has what he describes as a “first take” on Barr’s memo, which is to say a detailed critique of it on both constitutional and statutory grounds. On National Review’s website, by contrast, Andrew McCarthy declares the memo a “commendable piece of lawyering” and “exactly what we need and should want in an attorney general of the United States.”

Whatever Barr’s memo is, it is not that. Because whether one agrees with his view of the law (as does McCarthy) or recoils at it (as does Lederman), one thing attorneys general of the United States should certainly not do is make up facts. And ironically for a memo laying out the argument that Bob Mueller has made up a crime to investigate, the document is based entirely on made-up facts. Lederman mentions this point at the outset of his analysis:

the first huge and striking problem with Barr’s memo is that he unjustifiably makes countless assumptions about what Mueller is doing; about Mueller’s purported “theory” of presidential criminal culpability; about Mueller’s “sweeping” and “all-encompassing” “interpretation” of the statute and Constitution; about “Mueller’s core premise[s]”; . . . about “unprecedented” steps Mueller is proposing to take; about “Mueller’s proposed regime”; about “Mueller’s immediate target”; about Mueller’s presumed failure to “provide a standard” for what constitutes “corruptly” trying to impede proceedings; about Mueller’s “demands” that the President submit to interrogation; etc.

To read this memo, you’d think Barr were replying to a legal brief that Mueller had submitted in support of a prosecution of the President for obstruction of a federal proceeding. Yet as Barr concedes at the outset, he was “in the dark about many facts.” Indeed, he presumably was “in the dark” about virtually everything he wrote about. From all that appears, Barr was simply conjuring from whole cloth a preposterously long set of assumptions about how Special Counsel Mueller was adopting extreme and unprecedented-within-DOJ views about every pertinent question and investigatory decision—and that Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein was allowing him to do so, despite the fact that Mueller is required to “comply with the rules, regulations, procedures, practices and policies of the Department of Justice” and to “consult with appropriate offices within the Department for guidance with respect to established practices, policies and procedures of the Department.”

Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that Barr’s entire memo is predicated on two broad assumptions: first, that he knows Mueller’s legal theory, and second, that he understands the fact pattern Mueller is investigating. “It appears Mueller’s team is investigating a possible case of ‘obstruction’ by the President predicated substantially on his expression of hope that the Comey [sic] could eventually ‘let ... go’ of its investigation of Flynn and his action in firing Comey,” Barr writes in his second paragraph.

Neither assumption is, in our judgment, warranted. Unlike Barr, we don’t purport to know what Mueller’s obstruction theory is. It’s a subject about which one of us has been puzzling over a long period of time and in a number of articles. We also don’t purport to know what fact patterns Mueller is focusing on. But here’s a limb onto which we are prepared to venture: the reality is more complicated than the facts Barr has “assumed” for purposes of predicating nearly 20 pages of legal analysis. In fact, it’s a lot more complicated.

Barr assumes for the purpose of his memo that Mueller is only interested in presidential conduct sanctioned by Article II, specifically that his investigation revolves around Trump’s actions toward Comey. “As I understand the theory,” he writes, Mueller’s team has built their case on a novel and, in his view, unsupported interpretation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c)(2), the “residual clause” of § 1512, which prohibits witness tampering. § 1512(c)(2) holds that, “Whoever corruptly … otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so [is guilty of the crime of obstruction”—and Barr is concerned that Mueller is interpreting it to sanction an overly broad range of behavior.

Moreover, Barr takes the view that a facially lawful action taken by the president under his Article II authority cannot constitute obstruction as a matter of constitutional law. He expresses concern that allowing this interpretation to proceed could have “disastrous implications” for the executive branch and the presidency, potentially opening the door to criminal investigations of “all exercises of prosecutorial discretion.” He also writes, “if a [Justice Department] investigation is going to take down a democratically-elected president it is imperative… that any claim of wrongdoing is solidly based on a real crime—not a debatable one.” (All emphases in original).

It’s not clear why Barr adopts such a simplistic understanding of Mueller’s operating theory, but the sequence of events leading up to his submitting the memo in early June may offer some insight. At some point, probably in March or April of this year, the president’s legal team received a list of subjects that the special counsel’s office wanted to discuss with Trump in an interview. In late April 2018, the New York Times published a condensed list of those questions.

Several weeks later, on June 2, the Times published a letter from Trump’s then-lawyer, John Dowd, to Mueller, in which Dowd responded to Mueller’s request to question the president regarding 16 areas of interest—which essentially mirrored the reported list of questions. In that letter, Dowd explained to the special counsel why he is advising against the president granting the interview, including that he does not believe there is a cognizable offense for an obstruction investigation under 18 U.S.C. § 1505, which prohibits tampering with evidence and impeding legal “proceedings.” Dowd argued both that the president’s actions were authorized by Article II of the Constitution and that an FBI investigation does not count as a “proceeding.” His letter was mocked by a number of commentators on this latter point; Charlie Savage at the Times pointed out that by citing § 1505, instead of § 1512, Dowd was making things easy for himself. § 1512, unlike the statute Dowd cited, does not require that a proceeding be pending.

The Dowd letter, despite its flaws, sparked a certain amount of speculation in conservative media that Mueller lacked an actual crime to investigate—at least as to the obstruction cone of his investigation. A few days after the Times published the Dowd letter, for example, the National Review stated in an editorial that “The letter implies that these two events [the request to Comey regarding Flynn and his subsequent firing] remain the gravamen of the special counsel’s obstruction probe. If that is so, there is no obstruction case.” The editorial goes on to say that, “a prosecutor may not charge obstruction based on the president’s exercise of his constitutional prerogatives.” And it asserts that, in both instances, the president was acting within his constitutional authority:

In short, unless there is a smoking gun against the president that is lurking unseen even in the private jousting between Trump’s team and Mueller, the special prosecutor should be wrapping up the obstruction aspect of his probe rather than extending it via a court fight over the president’s testimony.

In was against this backdrop, on June 8, that Barr sent his memo to Rosenstein and Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel Steven Engel, a memo that shifts the discussion from § 1505 to § 1512 but also adopts the working understanding of the obstruction theory from Dowd’s letter.

The problem is that the facts are almost certainly more complicated than that.

Looking back at the New York Times list of subjects Mueller sought to discuss with Trump, many of those topics go well beyond core Article II-authorized management of the executive branch. For example, Mueller wanted to ask about what Trump knew “about phone calls that Mr. Flynn made with the Russian ambassador, Sergey I. Kislyak, in late December 2016.” Why Flynn lied about his communications with Kislyak is one of the key questions at issue in the case. And Barr himself makes clear that if a president induces someone to lie, that’s not an act protected by Article II.

Analysis of Trump’s inducing Flynn to lie would, of course, involve facts not in evidence, and it would almost certainly involve a different statute. But that’s precisely the point. How does Barr know what conduct Mueller is focused on or under what law?

There are other such examples—a number of them, in fact. Mueller wants to discuss “efforts . . . made to reach out to Mr. Flynn about seeking immunity or possible pardon.” That sounds more like a witness tampering investigation than a broad theory of obstruction under § 1512(c)(2). Mueller appears to want to discuss Trump’s efforts to get intelligence community leaders to lean on Comey to drop the Flynn matter and his “reaction to the news that [Mueller] was speaking to” those leaders. He’s also interested in the public bullying of Sessions and FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, both fired. Again, why is Barr so sure this is all a broad “residual” § 1512 theory of obstruction?

It may well be that Mueller’s theory of the case involves a narrower conception of what Article II permits the president to do than that which Barr holds. But our suspicion is that Mueller is looking not narrowly at the specific acts on which Dowd and Barr focused, but on a broader pattern of activity, some but not all of which involves facially valid exercises of Article II powers.

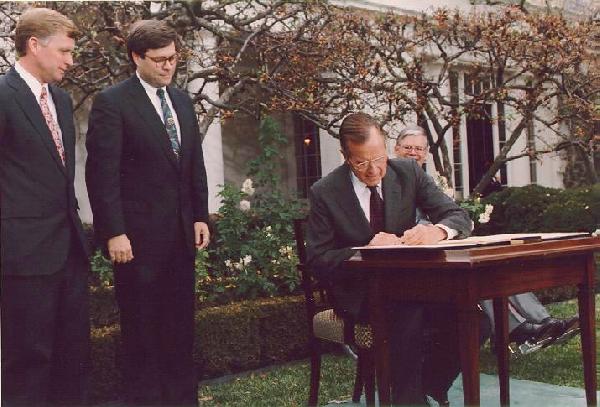

At a press conference today, Rosenstein declared that the Mueller investigation “is being handled appropriately.” When asked to weigh in on the memo, Rosenstein said that, “Bill Barr was an excellent attorney general during the approximately 14 months that he served in 1991 to 1993” and he predicted that he “will be an outstanding attorney general when he is confirmed next year.” But he added that the department’s handling of the obstruction matter has been “informed by our knowledge of the actual facts of the case, which Mr. Barr didn’t have.”

We suspect those “actual facts” will complicate the Article II analysis—both the facts under investigative scrutiny and the facts as to the range of statutes against which that evidence is being considered.

Editor's note: This piece has been edited to clarify the description of Barr's argument.