Challenging the Machine: Contestability in Government AI Systems

As government agencies move to adopt AI across a range of programs, choices made in system design can ensure individuals’ ability to effectively challenge decisions made about them.

In an October 2023 executive order, President Biden drew a highly detailed but largely aspirational road map for the safe and responsible development and use of artificial intelligence (AI). The executive order’s premise that AI “holds extraordinary potential for both promise and peril” is perhaps nowhere more clearly manifested than in efforts currently well underway to adopt AI and other advanced technologies in the administration of government programs.

When AI or other automated processes are used to make decisions about individuals—to grant or deny veterans’ benefits, to calculate a disabled person’s medical needs, or to target enforcement efforts—they directly implicate the principles of fairness and accountability called for in the executive order. But contestability—a person’s right to know why a government decision is being made and the opportunity to challenge the decision, tailored to the capacities and circumstances of those who are to be heard—is not merely a best practice.

Across a wide range of government decision-making, contestability is required under the Due Process Clause of the Constitution. Especially pertinent, given the complexity of many AI systems and the inscrutability of some, is the Supreme Court’s insistence on understandable notice: “An elementary and fundamental requirement of due process … is notice reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and afford them an opportunity to present their objections.” Additionally, federal laws establishing many programs require specific notice and right-to-be-heard procedures. Contestability can also serve other public interests: Challenging a specific decision can uncover systemic errors, contributing to ongoing improvements and saving money in the long run.

But what is meaningful contestability in practice? Especially when the current wave of AI development is driven by machine learning (ML) and, in particular, deep learning, with sometimes inconsistent or inexplicable results, how can government harness the power and reap the benefits of AI while enabling the contestability required by law and public obligation?

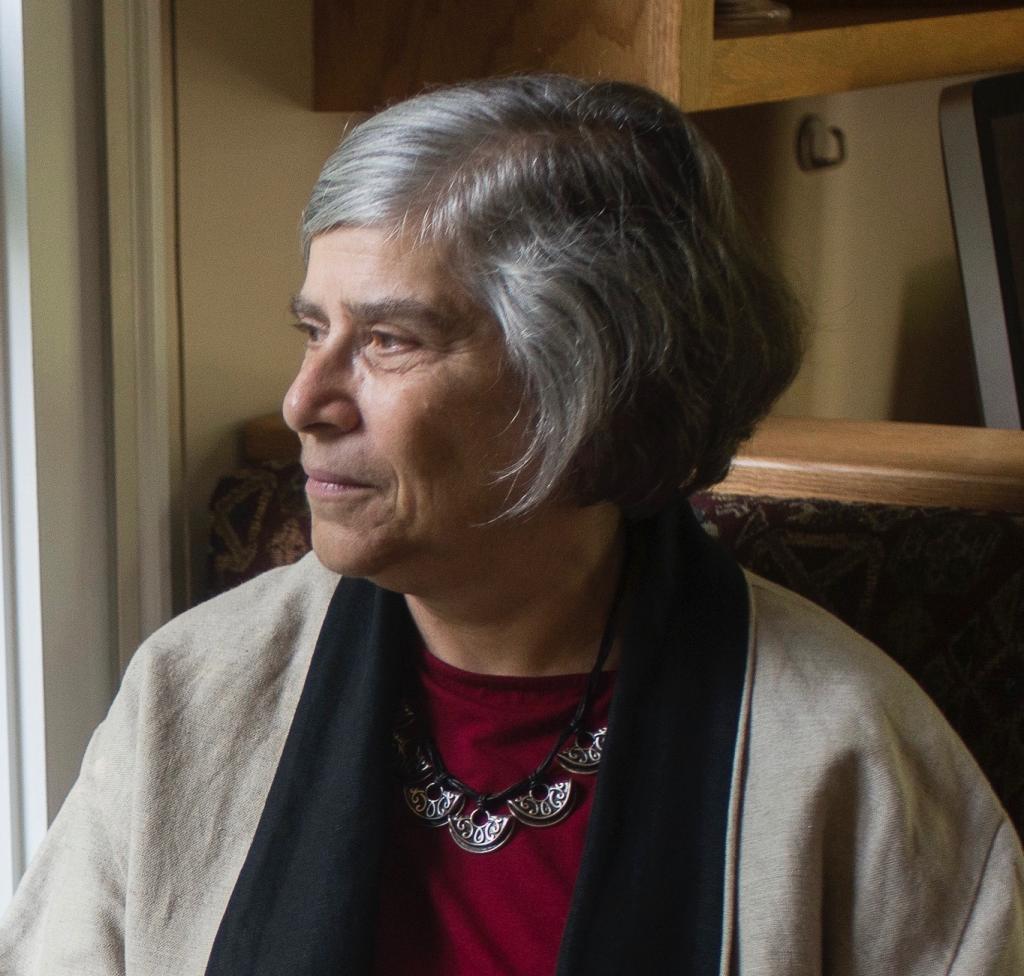

In January, working with Ece Kamar of Microsoft and Steven M. Bellovin of Columbia University, and with support from the National Science Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, we convened a workshop intended to address these questions and put some flesh on the bones of the Biden executive order. We brought together for two days a diverse group of government officials, representatives of leading technology companies, technology and policy experts from academia and the nonprofit sector, advocates, and stakeholders for a workshop on advanced automated decision-making, contestability, and the law. Some of the most compelling contributions to the dialogue at the workshop came from attorneys who struggle daily with government agencies that are using automated systems to make life-altering decisions about the lawyers’ clients. One participant in the workshop with severe physical disabilities, who requires intensive assistance in her daily activities, spoke about the difficulty of challenging the decisions of the Idaho agency that administers Medicaid after it adopted a new automated process for assessing need. Her presence gave reality to the human challenges of dealing with tech-driven government.

A person’s ability to challenge a decision made in whole or part by an automated system, even if constitutionally or statutorily required, can be limited when letters announcing a decision are opaque, if the internal mechanisms of a system are treated as trade secrets, or simply because of the resource imbalance between citizen and government. As automated systems become more advanced with the incorporation of ML and other AI technologies, contestability may become even more difficult to achieve.

This need not happen. Perhaps the most important finding to emerge from our workshop is that contestability of advanced systems, while difficult to achieve, is not impossible. Conscious choices made in system design can ensure that automated systems enable meaningful contestability, perhaps even better than current systems. When it comes to contestability, not all AI and ML techniques or capabilities are equal. Some may be incompatible with contestability, and those simply should not be used in systems making decisions about individuals.

Based on the input from our workshop participants, and drawing on earlier research, we developed 17 recommendations. Among them,

- Notice is a prerequisite of contestability. This means that notice to individuals that their case has been decided based in whole or in part on an automated process must be understandable and actionable. It also means there must be notice to the public before the decision is made to adopt AI or other advanced techniques for a system and then consultation as the system is being developed.

- Contestability must be incorporated into the system design, beginning with the decision whether to use an automated system in a decision-making or decision-supporting role at all. More detailed recommendations address how to achieve this objective, notably by involving those who will be directly affected by an automated system in design consultations and testing.

- The automated features of a system should never be allowed to supplant or displace the criteria specified in law for any given program or function. For example, if the legal standard for a disability benefit is “medical necessity,” the factors or criteria considered by the automated process should not be presumed to be the only way for an applicant to demonstrate medical necessity. Contestability design must include the right to present to the reviewing authority factors or criteria relevant to the legal standard that were not included in the automated process.

- Contestability features of a system must be stress tested with real-world examples and scenarios before field deployment (ensuring, of course, that individuals do not end up in a worse situation than under the previously fielded system).

- Integrating contestability considerations into the procurement process—the nuts and bolts of government contracting—is critical because many automated decision-making systems will be designed and built (and may be managed as a service) for the government by contractors. Solicitations and contracts must clearly require contractors to deliver contestability as a core system feature. Contractors should not be allowed to use assertions of trade secrecy or other intellectual property claims to frustrate contestation.

- Federal officials should ensure that contestability is required of the states implementing federal programs and of private companies whose systems, such as credit scoring, are used by the government in contexts affecting individuals.

- To ensure contestability, government officials overseeing the development and implementation of automated systems need to understand the technology and what can go wrong. The executive order recognizes that the government faces a talent gap and will have to undertake training itself, but it leaves that training to each agency head. That’s the wrong approach. The technology and its risks are cross-cutting. Officials of one agency need to learn from experiences at other agencies. Therefore, we recommend that the federal government establish a centralized AI governance institute, much the way it has established centralized training facilities for other skills, such as foreign languages.

In a matter of weeks, we will issue a full summary of the workshop with even more detail on how to provide contestability in practice. But given the haste with which AI and ML systems are being deployed, we did not want to delay offering our recommendations now. They should be directly relevant to efforts by the Office of Management and Budget to define minimum practices for government procurement and use of AI as well as to agency-specific initiatives to adopt AI.

As a major provider of services, a major purchaser of information technology, and a regulator of numerous private-sector functions that may include AI and ML, the federal government has a special responsibility to ensure that automated systems involving decision-making about individuals genuinely guarantee fairness, accountability, and transparency—including contestability.

Our recommendations should also guide the private sector. As federal regulators have noted, the development and use of advanced automated systems by the private sector is also subject to existing legal requirements intended to protect individuals. Designing for contestability could help satisfy these legal obligations, while also fulfilling industry commitments to the development of fair and just systems.