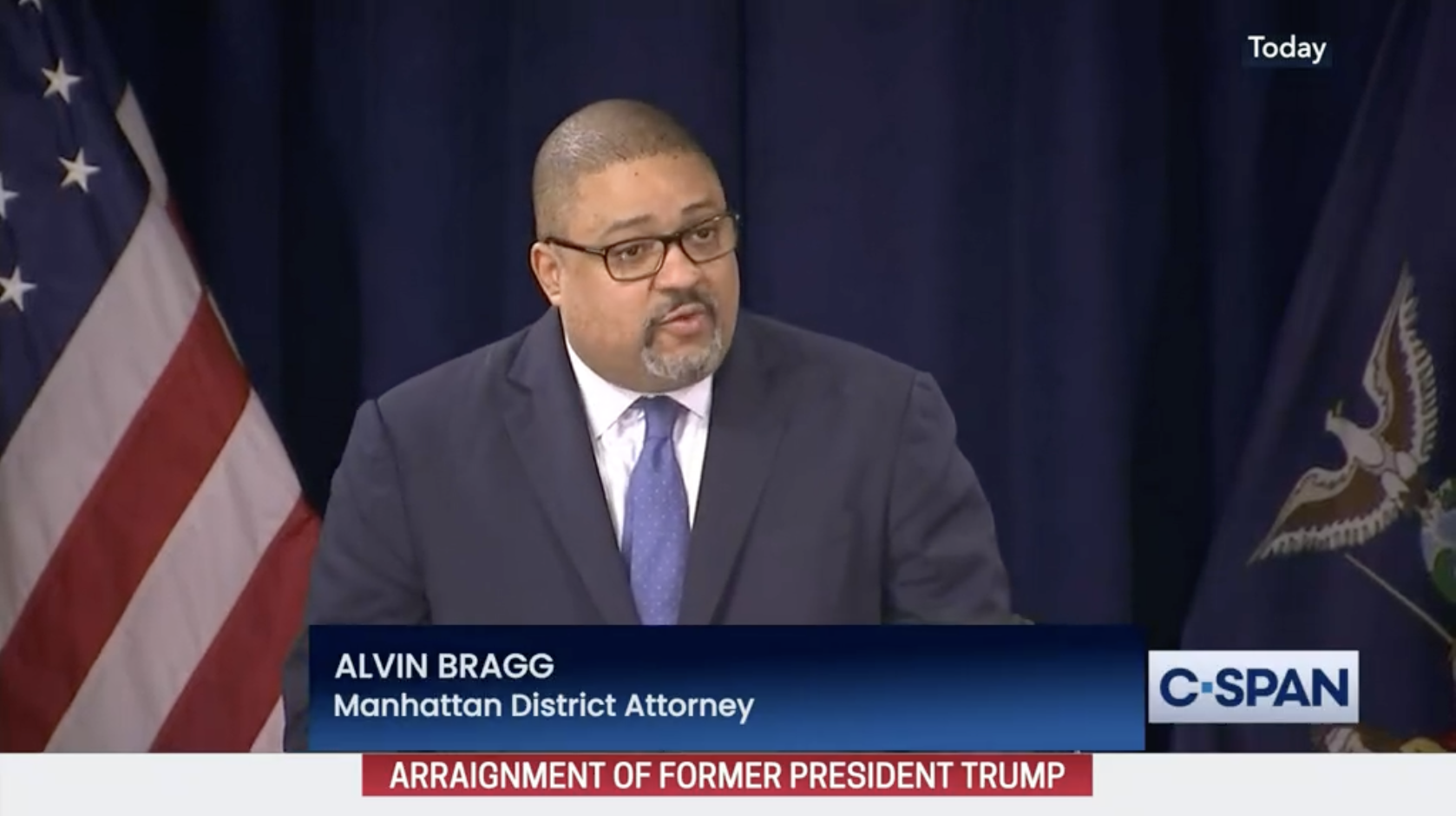

Charting the Legal Theory Behind People v. Trump

The mechanics of the case as District Attorney Alvin Bragg is prosecuting it.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

When Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg first brought charges against Donald Trump in March 2023, the legal theory behind the indictment remained remarkably unclear. Bragg had charged Trump under New York Penal Law § 175.10, falsifying business records in the first degree. The falsification of business records alone is a misdemeanor under § 175.05—but Bragg had boosted the charge to a felony by alleging that Trump fudged the records with the “intent to commit another crime and aid and conceal the commission thereof.” But what other crime? The indictment didn’t say.

Now, a year later, with the trial finally underway, Bragg’s legal theory has come into focus—if you know where to look. The charges against Trump still have an oddly inchoate quality, thanks to Bragg’s decision to charge § 175.10 without also charging alongside it the offense that elevated the alleged business records violation to a felony. But in court filings, opening statements, and one particularly informative conversation with Justice Juan Merchan, the district attorney’s office has made its thinking a great deal clearer. As the press corps straps in for what could be a long few weeks in New York Supreme Court, it’s worth taking a closer look at the legal mechanics underlying the allegations that Bragg’s office must now prove beyond a reasonable doubt.

Perhaps the charges against Trump are difficult to follow in part because the underlying facts are so byzantine. The 34 counts against Trump—all under § 175.10—each correspond to a business record allegedly falsified in service of covering up Trump’s link to the hush money payment provided to Stormy Daniels, an adult film actor and director, in October 2016. That month—at Trump’s instruction, Bragg argues—Trump’s fixer Michael Cohen paid Daniels $130,000 to remain silent about a past sexual encounter with Trump. The Trump Organization then paid Cohen back in increments from February through December 2017, with Cohen submitting invoices fraudulently labeled as charges for legal services under a retainer. The “business records” at issue in the indictment comprise Cohen’s invoices, the checks cut to repay him, and the internal records kept by the Trump Organization of these transactions—all of which were mislabeled, Bragg argues, to conceal the nature of the repayments.

So those are the business records. What about the “object crime”—that is, the crime that Trump allegedly intended to commit or conceal in such a way as to transform the underlying misdemeanor offense into a felony?

If you’re looking for the clearest statement of Bragg’s legal theory, you can find it in a November 2023 court filing opposing Trump’s motion to dismiss the case, along with Merchan’s ruling on that motion. Notably, in that ruling, Merchan clarified that § 175.10 “does not require that the ‘other crime’ actually be committed”—“all that is required is that defendant … acted with a conscious aim and objective to commit another crime.”

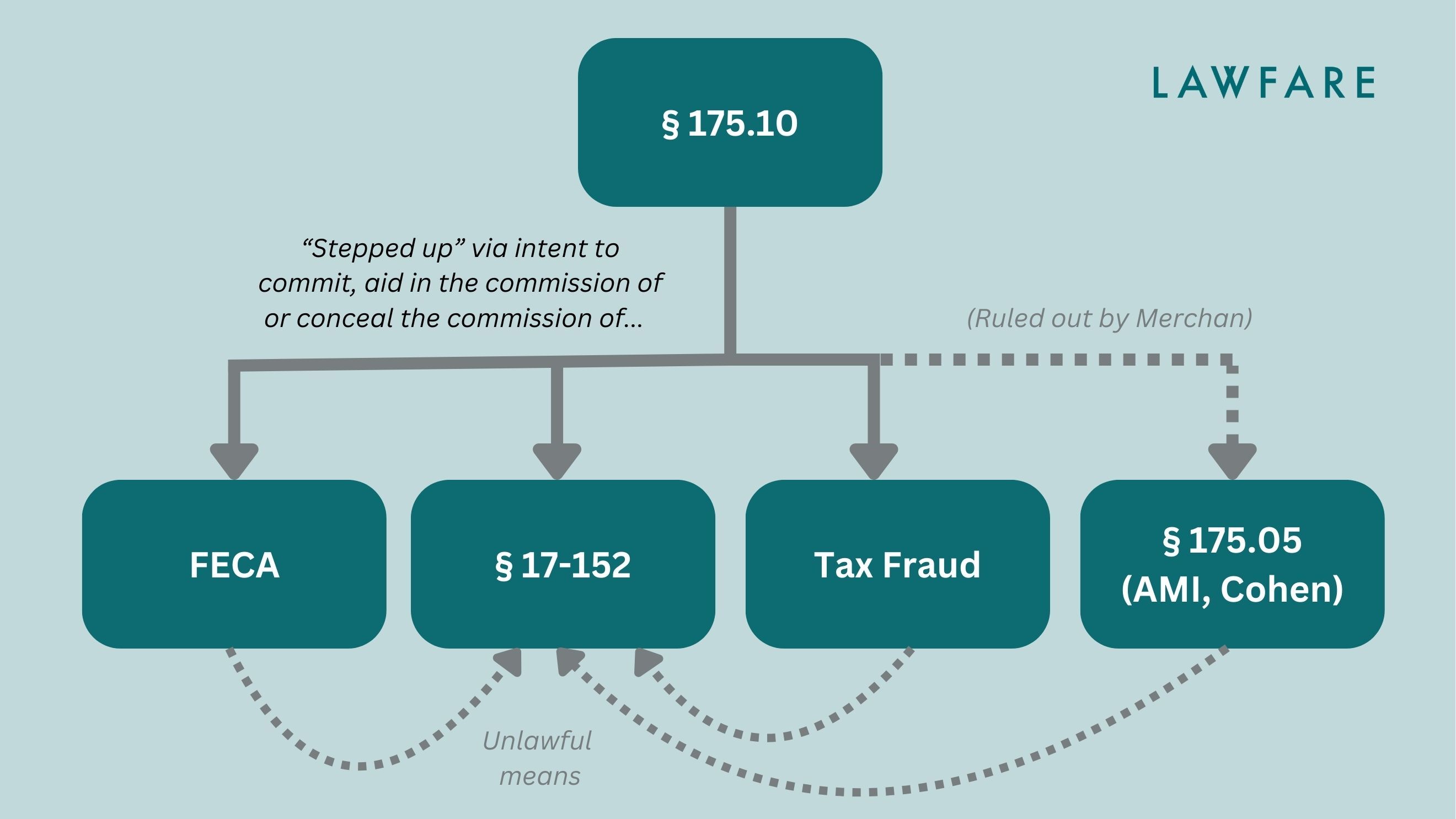

In his filing, Bragg sets out four potential object offenses: violations of federal campaign finance law under the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA); violations of New York Election Law § 17-152; violations of federal, local, and state tax law; and additional falsifications of business records outside the Trump Organization. Merchan allowed Bragg to move forward with the first three theories but tossed out the last one.

Before we begin, here’s a helpful chart to sketch things out.

.jpg?sfvrsn=6128ab6d_3)

The explanation below is not meant as an endorsement of Bragg’s legal theory, which has faced a wide array of criticism—some of it more careful than others. Trump has raised various challenges to the charges against him, all of which have failed so far but which he will likely raise on appeal if he is convicted. My goal here is just to set out the mechanics of the case as Bragg is prosecuting it.

The Potential Object Offenses: § 175.05

Let’s begin with that last offense. The underlying conduct here concerns records generated not just in the Stormy Daniels payment but also in the course of two additional efforts to squelch stories that might have harmed Trump—in both instances, with the central involvement of American Media Inc. (AMI), the parent company of the National Enquirer tabloid. The first story, which turned out not to be true, concerned an allegation by a Trump Tower doorman that Trump had fathered a child out of wedlock; the second was to Karen McDougal, a former Playboy model who says she had an affair with Trump. Trump, Bragg alleges, coordinated these payoffs with David Pecker, who purchased the rights to these stories with no intention of ever publishing them—a so-called “catch and kill.”

In the course of these purchases, according to Bragg, AMI fudged its own internal records—that’s the § 175.05 violation. Bragg also points to another § 175.05 violation in the form of false records generated by Michael Cohen when setting up the company, Essential Consultants LLC, through which he paid off Daniels. In Bragg’s telling, Cohen misrepresented the LLC’s purpose to the bank, presumably because he didn’t want to acknowledge that he was setting up a shell company to make a hush money payment.

Merchan tossed out this theory in his ruling on Trump’s motion to dismiss, writing somewhat tersely that “the Court is not convinced that this particular theory fits into the ‘other crime’ element of PL §.175.10.” He did, however, write that the § 175.05 theory appears to be “intertwined” with and “advances the other three theories discussed.” His ruling suggests that he will allow introduction of evidence of these other falsifications of business records for the purpose of proving the other three object crime theories.

The Potential Object Offenses: Tax Fraud

The potential tax fraud arises from the particular method by which the Trump Organization reimbursed Cohen for his payments to Daniels. Bragg alleges that “defendant reimbursed Cohen twice the amount he was owed for the payoff so Cohen could characterize the payments as income on his tax returns and still be left whole after paying approximately 50% in income taxes.” Here, Bragg points to federal, state, and local prohibitions on providing knowingly incorrect tax information.

The twist here is that because Cohen reported his income as greater than it actually was, he paid more in taxes, rather than less—which is probably not what most people have in mind when they think of tax fraud. On this point, Bragg argues that “[u]nder New York law, criminal tax fraud in the fifth degree does not require financial injury to the state” and that “[f]ederal tax law also imposes criminal liability in instances that do not involve underpayment of taxes.” Merchan seems to have been convinced, rejecting Trump’s argument “that the alleged New York State tax violation is of no consequence because the State of New York did not suffer any financial harm.” He does not explain further, simply writing, “This argument does not require further analysis.”

The Potential Object Offenses: Federal Election Law

More central to Bragg’s legal theory are violations of federal election law under FECA. Here, it’s useful to rewind a bit and recall the lay of the land before the Trump prosecution took place.

In 2018, Michael Cohen pleaded guilty in the Southern District of New York to federal charges including—among other things—campaign finance violations. Specifically, the statement of facts in Cohen’s case states that his payments to Daniels constituted a contribution to Trump’s campaign, well over the $2,700 limit in place in 2016 for individual contributions to a campaign during a single election. Additionally, Cohen admitted to helping AMI coordinate its payments to McDougal, which the Justice Department frames as unlawful corporate contributions to Trump’s campaign. AMI would soon reach a non-prosecution agreement with the Justice Department, in which the company admitted to knowingly making an unlawful contribution. A 2021 ruling by the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) also found that AMI “knowingly and willfully violated 52 U.S.C. §§ 30118(a) by making and consenting to prohibited corporate in-kind contributions with regard to payments related to Karen McDougal”—although this was not a finding of a criminal violation. (Under a conciliation agreement with the FEC, AMI paid $187,500 in fines.) What’s more, the government has said, Cohen and AMI further violated the law by failing to report their contributions.

For the purposes of his case against Trump, then, Bragg is arguing that Trump falsified the Trump Organization’s business records with the intent to criminally violate FECA. Ruling on Trump’s motion in limine, Merchan held that Bragg may not point to Cohen’s guilty plea or the Justice Department or FEC agreements with AMI as themselves evidence of Trump’s guilt, but that the district attorney may offer “testimony about the underlying facts … provided the proper foundation is laid.”

Trump has leveled multiple legal challenges against Bragg’s use of FECA as an object offense, arguing in his motion to dismiss that a violation of federal law can’t serve as the “other crime” under § 175.10. Merchan, however, held it could. Trump also argued that FECA preempts state law and thus rules out prosecution under § 175.10 with FECA as the object offense. Merchan rejected this argument as well, relying on a ruling last July to that effect by Judge Alvin Hellerstein of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in the context of rejecting Trump’s attempt to remove this case to federal court.

The Potential Object Offenses: New York Election Law

This brings us to the final potential object offense, and the one that seems to bear the most weight in Bragg’s presentation of the case so far: New York Election Law § 17-152, a misdemeanor offense that prohibits “conspir[ing] to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means.” Trump has sought to challenge Bragg’s use of this statute as well, arguing that it applies only to state and local elections, rather than presidential elections—which Merchan rejected. The former president likewise argued in federal court that FECA preempts § 17-152 in federal elections, but Judge Hellerstein held this to be “without merit.”

During opening statements on April 22, prosecutor Matthew Colangelo emphasized the role of § 17-152 in the district attorney’s case, declaring, “This was a planned, coordinated long-running conspiracy to influence the 2016 election, to help Donald Trump get elected.” Senior Trial Counsel Joshua Steinglass further underlined the importance of the statute the following day, describing § 17-152 as “the primary crime that we have alleged” as an object offense. “The entire case is predicated on the idea that there was a conspiracy to influence the election in 2016,” Steinglass said.

But § 17-152 requires that a conspiracy be carried out by “unlawful means”—so what “unlawful means” is Bragg alleging? Here, the legal theory loops back around to point to the other three potential object offenses: FECA violations, tax fraud, and AMI’s and Cohen’s misdemeanor falsifications of business records under § 175.05. (Note that while Merchan ruled out these third-party § 175.05 violations as object offenses for Trump’s violation of § 175.10, they’re still available to Bragg as a means by which to get to § 17-152.) Again, Bragg sets this out in his opposition to Trump’s motion to dismiss. Colangelo also gestured at this during his opening statement, describing the conspiracy as carried out “through illegal expenditures … using doctored corporate records and bank forms to conceal those payments along the way.”

Understanding this emphasizes the importance of the underlying FECA violations to Bragg’s case. The wrongdoing under federal campaign finance law supports two out of three remaining object offenses. Seen in a certain light, that makes it all the stranger that the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York itself never brought federal charges against Trump under FECA—a decision for which there has never been a public explanation.

Summing It All Up

Let’s return to our chart for a moment. Once we incorporate the “unlawful means” needed to reach the § 17-152 object offense, it looks like this:

Clear as mud?

In all seriousness, what this deep dive has hopefully shown is that Bragg’s legal theory is genuinely tangled—though the district attorney’s office is doing its best to clarify matters. The next few weeks will show whether he’s able to walk the jury through it.

.jpg?sfvrsn=8253205e_5)