Fireworks and Waterworks: Davidson and Hicks on the Stand

Previously on Trump New York Trial Dispatch: "Cornered By the 'Estrogen Mafia': Keith Davidson on the Stand"

May 2, 2024

It’s a foggy, misty morning at 100 Centre St., as a gaggle of press line up to enter Justice Juan Merchan’s courtroom for Day 10 of Trump’s criminal trial on 34 felony counts for falsification of business records.

It’s also a quiet morning, with nary a protester in sight. Collect Pond Park, just opposite the courthouse, is totally empty.

A lone protester arrives, ringing a replica of the Liberty Bell and waving a wooden Eastern Orthodox cross aloft. The back of his shirt reads: “THE 3 GREATEST U.S.A. PRESIDENTS: GEORGE WASHINGTON, JOHN F. KENNEDY, DONALD TRUMP,” but it’s unclear whether he is here chiefly to protest the trial or chiefly to bless us all. He is a momentary spectacle, in any event, gone in the time it takes to compose a tweet.

To pass the time, a German reporter teaches his American counterpart how to say “hush money”—Schweigegeld—but laments that it sounds better in English.

“My god,” she replies with interest. “So how do you say pornstar?”

Pornostar. Or, the reporter thinks for a second, perhaps Sexfilm für Erwachsene, which directly translates to “sexfilm for adults.”

The language lessons don’t stop there. In the courtroom, while waiting for the proceedings to begin, a French reporter also translates key trial vocabulary: hush money is pots-de-vin, literally “pot of wine.” How very French, the American reporters all agree.

Later, one of the witnesses, former lawyer to Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal Keith Davidson, will offer a few English language lessons of his own, revealing his own interpretation of what such terms as “hush money,” “romantic,” “sexual,” “relationship,” and “extraction” mean. But that will come later.

* * *

First, we have to have a second hearing to determine whether to hold the defendant, Donald Trump, in criminal contempt of court for violating Justice Merchan’s gag order. Two days ago, the judge found Trump in criminal contempt for violating his gag order nine times (out of 10 allegations), fining him $1,000 for each count. (The order is available here; our coverage is available here.) Today, we will hear argument regarding four additional alleged violations.

At 9:20 a.m., Trump sits with his defense counsel—Todd Blanche to his right, Emil Bove to his left, and Susan Necheles to Bove's left. Pool photographers snap away at Trump in gold tie and dark navy suit.

The prosecution is here too, as Assistant District Attorneys Susan Hoffinger, Matthew Colangelo, and Christopher Conroy unload a few documents as their co-counsel, Assistant District Attorney Joshua Steinglass, chats collegially with Blanche.

Also in the courtroom is Boris Epshteyn, who was recently indicted alongside Rudy Giuliani, Mark Meadows, and other Trump affiliates in Arizona on charges related to the 2020 election.

At 9:30 a.m., the ever-punctual Justice Juan Merchan strolls in—resplendent in his robes, the fluorescent light glinting off of his salt-and-pepper hair, judicial authority, as always, radiating from his very presence and being.

Our regular cast of characters makes the pro forma introductions, as Justice Merchan greets them.

“Good morning, Mr. Trump,” the judge says, mentioning that he asked the jury to arrive a little late today in order to have the contempt hearing.

The prosecution has provided the court four exhibits, one for each of the alleged violations, and the defense has also distributed its own exhibits, whose pages numbered close to 500.

“People, why don't we begin with you going through each of the violations, and explain to me why you believe that it constitutes a violation,” suggests Justice Merchan.

Conroy takes the lectern for the prosecution and mentions that he will not play the videos but will instead quote the language used. The prosecutor begins by addressing Trump’s complaint that the gag order is allowing his political opponents to attack him while forbidding him to respond. Instead, Conroy says, the gag order was issued because of Trump’s “persistent and escalating rhetoric aimed” at witnesses and jurors, noting also the nine previous violations in this case.

We start with Exhibit F from the prosecution’s second supplemental affirmation, an April 22 phone interview with “Real America’s Voice,” in which Trump said just hours before the last contempt hearing: “[T]his Judge said that I can't get away from the trial. You know, he is rushing the trial like crazy. Nobody has ever seen a thing like this. That jury was picked so fast, 95 percent Democrats.” Conroy argues that the statement was not aimed at “any jurors,” but rather “these jurors, in this case, sitting right in this room in a few minutes.”

The second alleged violation, Exhibit H, is from the morning of April 25. At a press event, in response to a question about witness David Pecker’s testimony thus far, Trump responded, “He's been very nice. I mean, he's been — David's been very nice. A nice guy.” Conroy calls this a “classic carrot stick” and elaborates that Trump seems to be saying: “Pecker, be nice ... I have a platform, and I will talk about you, so be nice.”

Exhibit G, the third statement, is a transcript from an interview Trump gave to a Pennsylvania TV station interview on April 23, during which he called forthcoming witness Michael Cohen “a convicted liar” and “a convicted lawyer” with “no credibility whatsoever.” Conroy says there's no question that this is related to the trial, and that it’s “clearly willful, clearly knowing.”

“The Defendant thinks the rules should be different for him,” Conroy says. Then, as if anticipating the defense’s argument regarding this particular witness, he continues, “I talked a bit about the impact of comments about a testifying witness, perhaps not on that witness”—meaning Cohen—“but on other witnesses, it is an insidious thing.”

His point is that while Cohen might not need protection from the court, what Trump is doing to Cohen might deter other witnesses from testifying and bring his wrath down on them.

Trump keeps his eyes closed as we move to the last alleged violation, Exhibit E, a statement also about Cohen from April 22 “made right outside of these doors, the doors of this courtroom in the little pen that's set up where he speaks to the gathered media everyday,” Conroy says.

“This is the most critical time—the time the proceeding needs to be protected,” Conroy says, as he closes by addressing Trump’s comments about Cohen. “Michael Cohen is not a political opponent,” he says, pushing back against Trump’s argument that his comments relate to issues at the heart of this proceeding and Cohen’s participation in it, rather than Trump’s “political policies or goals.”

The prosecution again seeks a maximum penalty of $1,000 per count, but does not—yet—seek jail time.

Blanche stands to replace Conroy at the podium. He starts his rebuttal by acknowledging that the purpose of the gag order is to “protect the integrity of these proceedings” and not to “allow unfettered attacks on President Trump, recognizing he is running for President, doing a campaign, every day.” There’s also no dispute, Blanche says, “that political attacks and responses to political attacks” do not violate the gag order.

With that, Blanche starts his narrative in November 2022, when Trump announced his candidacy for reelection, and the “multiple and repeated attacks” from Cohen and people on Cohen’s podcast that have occurred since.

“If I can make a suggestion, Mr. Blanche,” Justice Merchan cuts in. “My main concern is the conduct that took place after the gag order was implemented.” Blanche promises the judge that he does not plan to go through all 500 pages of exhibits, and Justice Merchan puts a finer point on his earlier suggestion: “It’s not going to weigh very heavily on my decision if you refer to exhibits [from] a year ago or two years ago before the gag order was in place.”

Blanche says he just wants to keep things in perspective “beyond just the gag order.”

“You can do that. I'm telling you what I'm going to consider,” Merchan replies quickly.

Blanche starts again with a reference to President Biden’s comment at the April 27 White House Correspondents’ Dinner, in which he quipped, “Donald has had a few tough days lately. You might call it Stormy weather”—an obvious reference to witness Stormy Daniels, says Blanche.

Blanche suggests that the gag order prevents Trump from responding to statements like that, but Justice Merchan is skeptical. “No, he is not allowed to refer to a foreseeable witness in the case,” the judge reiterates, but nothing in the gag order prevents Trump from responding to Biden.

We move on, and Blanche refers to a number of exhibits (including posts by Cohen, transcripts from Cohen’s podcast, and video transcripts), and he hands up a thumb drive of additional exhibits.

We’ll get to Cohen soon, but Blanche wants to talk about Pecker first. Blanche defends Trump’s comments on Pecker, which he depicts as “a very factual, truthful answer,” neither a “warning” nor a “willful violation.”

“It’s not just about Mr. Pecker,” Justice Merchan pushes back. “It's about what all the other witnesses who may come here see.”

Blanche changes tack, calling attention to the unfairness of the gag order because of “what's happening behind us”—a reference to the 24/7 media coverage of everything that’s happening and everything witnesses are saying. In the press room, there’s an unsettling feeling as Blanche breaks the fourth wall, and not for the first time in this trial.

Justice Merchan appears skeptical of this tack as well. “What's happening in this trial is no surprise to anyone,” he says. “The former president of the United States is on trial ... It’s not surprising that we have press here. We have press in the overflow room.” The fourth wall lies in ruins. “So, I don't see how it would press on Mr. Trump if ten outlets are talking about Mr. Pecker,” he finishes.

Blanche may be feeling déjà-vu, because this contempt hearing is going about as well as the last one—which is to say that it is not going well at all. But he can’t be remotely surprised by that, given what his client has done. And he’s a gamer, in any case, which a lawyer has to be if he is to manage the relationship between this client and a trial judge.

So he shifts gears a bit and complains that the witnesses and press can say whatever they want. This does not impress Justice Merchan, who points out that they’re not subject to the gag order; this scores a few chuckles from the press. “That's a very significant issue you're overlooking,” Justice Merchan continues. “I don't have authority over the press. I don't have authority over most of the people that are saying things.”

Justice Merchan here is politely not pointing out that the reason he lacks authority over the press corps and the witnesses is that they have not been indicted on 34 felony counts and are thus not facing trial in his courtroom.

We set aside this rather inconvenient, and as yet unspoken, truth as Blanche homes in on one aspect of the gag order: whether Trump willfully violated it. Justice Merchan cuts in again, pointing out that in the first exhibit, Trump went to the press. The press didn’t go to Trump. In fact, he quite literally could have gone out a different door, one set aside for his own use, to avoid reporters.

“Nobody forced your client to go stand where he did that day,” says Justice Merchan.

“Judge …,” Blanche begins, faltering. “I agree with that,” he says defeatedly, winning a big laugh from the press room. But in the courtroom itself a different audience seems unamused. Trump demonstratively wheels around to his right to face Blanche. He looks stricken, as though Blanche’s even tactically conceding a rhetorical point to the judge for purposes of an argument constitutes a huge betrayal. He then reaches for a note pad and appears to write something on it.

Blanche now mentions that he wants to address the statements about Cohen, but he turns first to Trump’s comments about Pecker and the nature of Pecker’s testimony. After a minute or so, Justice Merchan waves him off. “Just to save you time, I am not terribly concerned with that one,” he says. “I think that there are situations where comments like that could be of much greater concern.”

Taking what appears to be a small win in stride, Blanche moves breezily back to Trump’s comments regarding Cohen.

“Very quickly, please,” Justice Merchan urges Blanche, as the lawyer puts a few exhibits on the screen. Cohen, Blanche argues, “has been inviting and almost daring President Trump to respond to everything he has been saying,” including “mocking him for being on trial and also his candidacy.”

He produces evidence of that mockery, including one of Cohen’s posts with a caption directed at Trump that, “I won't send any money to your commissary,” and another with an AI-generated photo of Trump in an orange cape with the caption “SUPER VICTIM.” Still another, Cohen’s “Von ShitzInPantz” post, gets an especially hearty laugh from the press, while the French- and German-language reporters face the challenge of translating the phrase in real time to their readers.

As he attempts to move through more exhibits designed to show that Trump is just responding to taunting by the witness, Justice Merchan steps in: “You made your point.” Blanche relents, but he makes an additional point that Cohen has repeatedly attacked Trump on his podcast, Mea Culpa, on which, according to Blanche, “multiple” members of the press present in this very room have joined. (Note: No one employed by Lawfare has ever appeared on Michael Cohen’s podcast. Cohen invited Benjamin Wittes on the show at one point, but Wittes declined.)

Blanche has more points yet to make. As is reported, “because it's true,” Blanche adds, Cohen has been taking to TikTok nightly, “literally making money” by criticizing Trump. “This is not a man who needs protection from the gag order,” Blanche says of Cohen, echoing Conroy’s earlier argument.

Justice Merchan wants to move on to comments made about the jury, and something in his voice betrays the feeling that this is his biggest concern.

“We very much believe that this is a political persecution, and this is a political trial,” Blanche offers. “And part of that belief and part of President Trump's belief is the location of this trial.”

He continues, but Justice Merchan now heads him off: “Did he violate the gag order? That's all I want to know.” After a brief back and forth, he tells Blanche flat out that he’s not accepting his arguments on the larger point of the legitimacy of the trial or its presence in the Manhattan.

“Okay, it’s ten after ten,” says Justice Merchan—ten minutes past when he told the jury to be ready. “Is there anything you would like to say just to wrap it up?” Blanche halfheartedly rehashes a few of his previous arguments, until the judge ends the hearing.

“I understand your argument, thank you,” Justice Merchan says conclusively, breaking for five minutes to bring in the jury and witness.

* * *

At 10:18 a.m., Keith Davidson, Tuesday’s witness, is back on the stand.

We resume the direct examination with email exchanges between Davidson and Cohen. Steinglass asks Davidson to read an Oct. 26, 2016, email from Dylan Howard to himself and Cohen, confirming an agreement on “Keith’s client.”

Steinglass inquires what this email was about, and Davidson takes a long, careful pause, as if easing back into another long day of testimony. The email followed a conference call between the three men, Davidson says, because there was “difficulty in communications” with Cohen, in whom Davidson had lost trust, necessitating Howard’s role as “mediator.”

Why the loss of trust? “I believed he was not telling me the truth,” says Davidson, regarding “delays in funding” the Stormy Daniels deal.

Steinglass asks Davidson to read through more correspondence between him and Cohen, beginning with an Oct. 27, 2016, email with the subject line: “Re: wire on behalf of Essential Consultants LLC.” In the email chain, Davidson confirms to Cohen that he had received a wire transfer.

Now Steinglass throws onto the screen a string of texts between Davidson and Howard, also from Oct. 27, 2016.

“Money wired I am told,” Howard texted Davidson, who took that to mean Cohen told Howard about the wire. Then:

Davidson: “Funds received.”

Howard: “Unbelievable.”

Davidson: “Was never really sure…”

As Davidson reads transcripts of his words and others, and replies monosyllabically to Steinglass’s questions, he does so carefully, pausing frequently to get things right, betraying few emotions. He plays the consummate professional.

He confirms that Daniels re-signed the original settlement agreement and side letter agreement and that the name of the funder had been changed from Resolution Consultants to Essential Consultants.

The contract between Daniels (using the pseudonym PEGGY PETERSON) and Trump (under the pseudonym DAVID DENNISON, named after a hockey teammate of Davidson’s) appears on the screen, and Steinglass homes in on page 3, paragraph D, which Davidson says is “essentially part of the nondisclosure aspect of the agreement.”

Steinglass moves on to the liquidated damages provision of contract—one million dollars per breach—added at Cohen’s request. It’s an unusually large sum, given that the amount is dramatically in excess of the original payment under the NDA; Davidson, in all his lawyerly scrutiny, says he believed the paragraph was unenforceable. Why? “Because the Liquidated Damages Provision would have no relation to the damages caused if there was a breach,” Davidson explains in an almost bored tone.

We skip to the end and see that Daniels and Cohen signed the agreement on Oct. 28, 2016, and Davidson signed a few days later, on Halloween.

The line for DAVID DENNISON, aka Donald Trump, is left blank.

“So, Mr. Davidson, how much money did you personally make for this deal?” Steinglass asks. Davidson says that he made $10,000, but when Steinglass asks approximately how much money he disbursed to Daniels, after having received the wire transfer from Cohen, Davidson puts a wall up.

“I fear that invades attorney-client privilege,” Davidson says. Steinglass asks another way, to which Davidson vaguely responds, “I disbursed everything pursuant to my client's directives.”

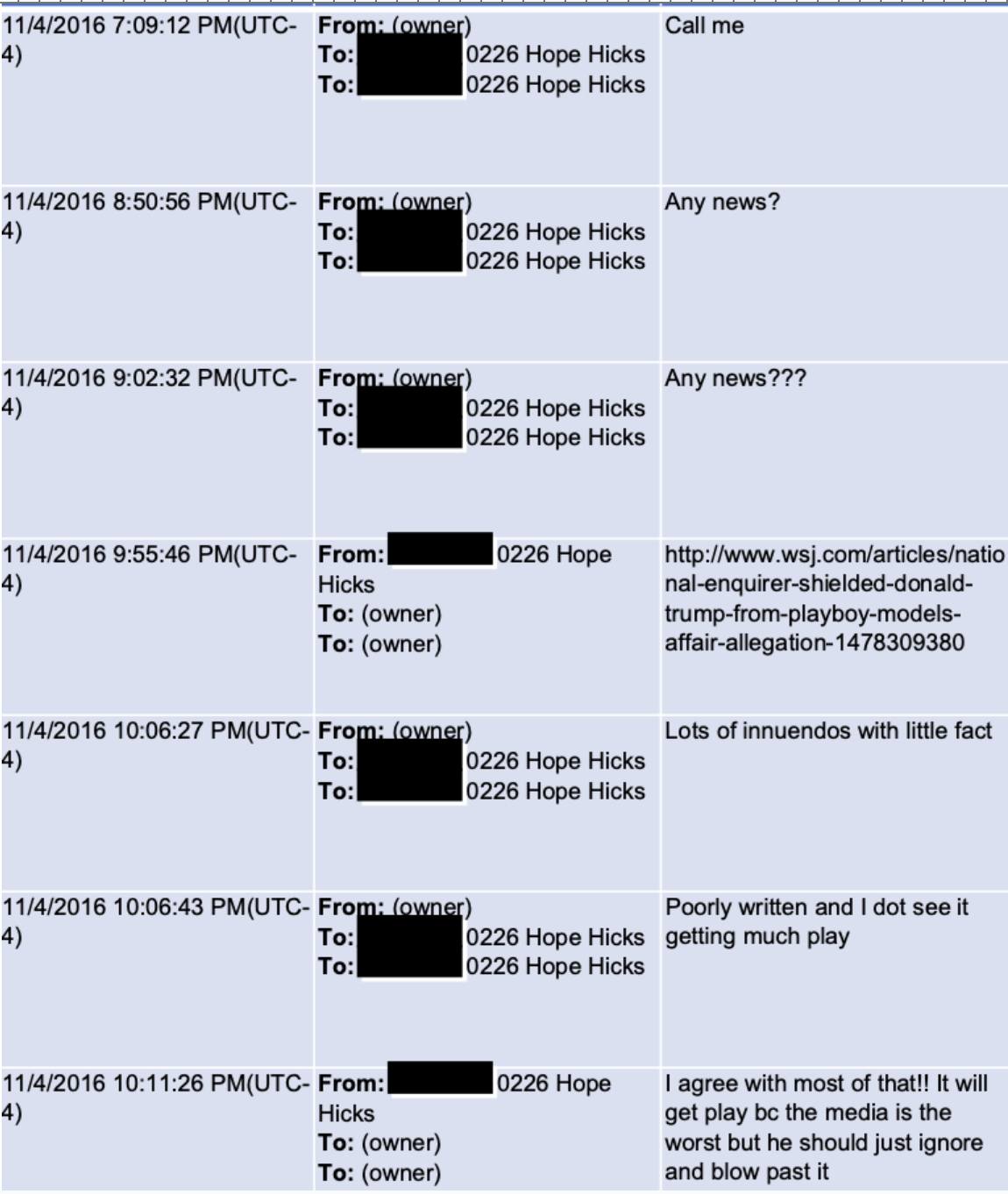

Steinglass moves on from the agreement and a Wall Street Journal article from Nov. 4, 2016, flashes on screen. The headline reads: “National Enquirer Shielded Donald Trump From Playboy Model’s Affair Allegation.”

Davidson recalls that Cohen and “his boss” were “very upset” that the article had been published, especially at the timing of it, and Cohen wanted to know who the source was. Cohen also threatened to sue McDougal, whose whereabouts at the time of publication Davidson can’t recall.

We move forward in time a few days to election night—Nov. 8, 2016—with more texts between Davidson and Howard.

“What have we done?” Davidson texted Howard. The witness explains that this was “sort of gallows humor,” which was apparently not lost on a few members of the press who giggled when the text appeared on screen. Davidson elaborates that he sent this text as the results were coming in, and broadcasters had begun to call the election for Trump, to the surprise of many.

“This is a text between Dylan Howard and I, and that there was an understanding that our efforts may have in some way—” Davidson says, but stops himself. “I should strike that.” He begins again: “This was an understanding that our activities may have in some way assisted the presidential campaign of Donald Trump.”

“Oh my God,” Howard responded in a text of his own.

After the election, Davidson says Cohen called “fairly frequently.” One of those calls looms large in Davidson’s memory because of the setting. It was Dec. 9, 2016, and he was shopping in a “a department store—which is kind of a whole nother story because it was sort of strangely decorated,” Davidson says in a rare digression.

On the call, a “depressed and despondent” Cohen told Davidson something to the effect of: “Jesus Christ. Can you fucking believe I'm not going to Washington. After everything I've done for that fucking guy. I can't believe I'm not going to Washington. I've saved that guy's ass so many times, you don't even know. That fucking guy is not even paying me the $130,000 back.”

“I'm almost afraid to ask this question, but how was the store decorated?” Steinglass asks, much to the delight of members of the press—every last one of whom is thinking the exact same question.

“It was decorated like Alice In Wonderland, and so you felt very small in it,” Davidson says with genuine horror. Confused laughter ripples through the press room as Davidson takes everyone down the rabbit hole. “And there were these huge rabbits and a cat in the hat on the ceiling and things like that. It was just a very odd feeling.”

A chilling scene, to be sure.

Davidson regains his composure as Steinglass, undeterred by the psychedelic interlude, fast forwards to January 2018.

During that time, Davidson says he received a request for comment from the Wall Street Journal, which led him to believe the paper was getting ready to publish another article, this time about the payment of Daniels to the benefit of Trump.

“Nothing about the present day regurgitation of these rumors causes us to rethink our prior denial issued in 2011,” Davidson had responded, referencing the cease-and-desist demand letter that he had sent to TheDirty.com back in 2011. He forwarded this response to Cohen, in light of their “mutuality of interest” and pursuant to their agreement.

Trump sits low in his chair, eyes closed, head moving side-to-side occasionally. He opens his eyes to say something to Blanche, who leans in close.

More texts between Davidson and Cohen now appear on the screen.

“Write a strong denial comment for [Daniels] like you did before,” Cohen instructed Davidson via text on Jan. 10, 2018.

“A denial of what?” Steinglass asks.

“Everything,” says Davidson.

“Including a sexual encounter with Trump?” Steinglass asks.

“Yes,” Davidson answers.

Steinglass displays the aforementioned “strong denial comment” dated Jan. 10, 2018, and signed by Daniels. It reads:

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

I recently became aware that certain news outlets are alleging that I had a sexual and/or romantic affair with Donald Trump many, many, many years ago. I am stating with complete clarity that this is absolutely false. My involvement with Donald Trump was limited to a few public appearances and nothing more. When I met Donald Trump, he was gracious, professional and a complete gentleman to me and EVERYONE in my presence.

Rumors that I have received hush money from Donald Trump are completely false. If indeed I did have a relationship with Donald Trump, trust me, you wouldn't be reading about it in the news, you would be reading about it in my book. But the fact of the matter is, these stories are not true.

Stormy Daniels

“How would you characterize, Mr. Davidson, the truthfulness of this statement?” Steinglass asks, as the press chuckles.

To everyone’s surprise, Davidson does not treat this as a rhetorical question designed to elicit his testimony that the statement was a bald-faced lie on all points.

Rather, in the first indication that Davidson is going to morph before our eyes into something very different from the professional lawyer-with-some-oddball-LA-clients he has presented himself as so far, Davidson describes the statement as a “tactic” in the “cat and mouse interactions between publicists and attorneys and the press.” He says that an “extremely strict reading of this denial would technically be true.”

He proceeds with his close reading, akin to a high school English class dissecting a sonnet. The truthfulness, as it turns out, turns on the “definition of romantic, sexual, and affair.” It’s like when Bill Clinton declared before a federal grand jury that it “depends what the meaning of ‘is’ is”—only if he had said, “it depends what the meaning of romantic, sexual, and affair” is.

How can this statement possibly be read to be true?

Davidson begins his exegesis.

“Well, I don't think that anyone had ever alleged that any interaction between she and Mr. Trump was romantic,” Davidson says with a sheepish look. The press cracks up. This is really good content.

Did you understand this statement to be cleverly misleading?” Steinglass wonders.

“I don’t understand the question,” Davidson responds with lawyerly temerity.

But what about “sexual”? Well, it says “sexual and/or romantic,” Davidson replies. There was nothing romantic about this encounter, he seems to be suggesting.

He doesn’t appear to be joking. Or if he is, Davidson is completely committed to the bit.

Steinglass moves on to the line “Rumors that I received hush money from Donald Trump are completely false,” but Davidson once again defends the truth of the statement. “It wasn't a payoff and it wasn't hush money,” he says. “It was consideration in a civil settlement agreement.”

Unable to hack his way through Davidson’s wordplay, Steinglass moves on to more texts from January 2018 between the witness and Cohen, during one of Cohen’s “pants on fire stages,” in which he was “frantically trying to address the fact that Stormy's story had percolated into public consumption,” as Davidson puts it.

“Keith, the wise men all believe the story is dying and don't think it's smart for her to do any interviews,” Cohen texted Davidson. “Let her do her thing but no interviews at all with anyone.” Davidson agreed.

Steinglass now displays more texts between Cohen and Davidson, who reads through the transcript slowly, punctuating each word in a staccato rhythm. When it became clear that Daniels would appear on the Jimmy Kimmel show, Cohen requested another denial statement from her to be released prior to her appearance. Davidson had prepared the statement at the Marilyn Monroe suite at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, California, where the Jimmy Kimmel show had put Daniels up.

We see the statement on screen. It reads:

To Whom It May Concern:

Over the past few weeks I have been asked countless times to comment on reports of an alleged sexual relationship I had with Donald Trump many, many, many years ago.

The fact of the matter is that each party to this alleged affair denied its existence in 2006, 2011, 2016, 2017 and now again in 2018. I am not denying this affair because I was paid "hush money" as has been reported in overseas owned tabloids. I am denying this affair because it never happened.

I will have no further comment on this matter. Please feel free to check me out on Instagram at @thestormydaniels.

Thank you,

Stormy Daniels

Once the press room laughter dies down at the last line, Steinglass asks Davidson once again about the truthfulness of this statement. And once again, the lawyer-witness calls it “technically true.” Why? No one has ever alleged Daniels and Trump had a “relationship,” Davidson explains, because a “relationship” requires “ongoing interaction.”

But later that night, Daniels appeared on Kimmel and discussed her affair with Trump, much to the chagrin of both Cohen and Davidson. Text messages now on screen chronicle the two men’s reaction to the interview in real time.

Cohen: “She just denied the letter.”

Cohen: “Claiming it's not her signature.”

Cohen: “You said she did it in front of you.”

Davidson: “She did. Impossible—she posted it on her own twitter page.”

Cohen: “They showed her signature and she claimed it was not hers on Kimmel.”

Davidson: “WTF.”

“It's sort of an—it's a signal of exasperation of: What the fuck,” Davidson explains, getting quite the laugh from the press.

Davidson explains that he was in a tough spot after Daniels's appearance on Kimmel. He was “trying to thread the needle and hold off allegations of breach and all the penalties that would come with that.” He testifies that he was “trying to placate [Cohen] while also trying to meet Stormy's desires.”

Davidson, it seems, did not manage to placate Cohen, who repeatedly threatened to sue Daniels. Cohen could be a “very aggressive guy,” Davidson says, one who would “make legal threats, say that he would bankrupt [Daniels] and, ‘Rain legal hell down upon her,’” and say things like “Don't fuck with us. You don't know who you're fucking with.”

Davidson reviews yet more texts in which he explains that Cohen was under some fire and wanted validation or corroboration that the $130,000 was, in fact, paid by Cohen and not somebody else. He asked Davidson to write something to that effect to send to Chris Cuomo.

Though Davidson had said yesterday that he believed the ultimate source of the funds was Trump, he maintains that at the time, he believed that Cohen had used his own funds.

Steinglass asks Justice Merchan permission to step away from the lectern for a moment to consult with fellow counsel.

When he returns, he asks one final question: “Mr. Davidson do you have any stake in the outcome of this trial?”

“None whatsoever,” Davidson responds.

With no further questions, we take a brief recess.

* * *

At 11:56 a.m., Justice Merchan is back on the bench, Davidson is back on the stand, and the jurors are back in the box.

Emil Bove for the defense begins the cross. A fierce battle ensues between him and Davidson, who transforms before the jury’s, and our, eyes into a kind of monster. Nothing about the direct examination prepares us for what emerges on cross-examination. Anyone who tells you with confidence how the jury will react to this exchange is blowing smoke. It is a completely astonishing fireworks display.

Under questioning from Bove, Davidson confirms he has never met nor spoken to Trump, and that he has no firsthand knowledge of the Trump Organization. Bove asks him, therefore, whether everything Davidson knows about Trump “came from either TV or Michael Cohen.”

“I have had no personal interactions with Donald Trump,” Davidson replies. “And either it came from my clients, Michael Cohen, and from some other source, but certainly not from him.”

Bove now asks Davidson about his close relationship with Dylan Howard, whom he had known for more than a decade. Davidson says it was close, though he can't recall the starting point or how they came to know one another.

Would it surprise you to learn, Bove asks, that Howard considered you to be a major source of info for himself? Yes, Davidson responds, that would surprise me.

Bove asks Davidson whether it’s really true that Karen McDougal didn't want to go public with the claims discussed here. Davidson reconfirms to Bove that she didn’t.

In response to a series of questions, Bove elicits from him once again that she had three goals. One was to rejuvenate her career. She had a "real career," he affirms. She had been on magazine covers, Bove encourages.

“More than that. Yeah,” Davidson responds, apparently referring to her Playboy centerfold days. “She had a very healthy career.”

Bove pushes: But not just nude modeling, right? She also had a fitness modeling career right? Davidson agrees.

Bove: “There was ongoing value in her image and likeness, right?”

Davidson: “Yes.”

Another goal was to make money? Yes.

A third goal was to avoid telling her story, something that McDougal herself said in an interview with Anderson Cooper. Davidson assents here, too.

Bove now turns the focus to Cohen, eliciting from Davidson that he first dealt with Cohen back in 2011, when a publication called TheDirty.com published an article about the Daniels-Trump liaison and Daniels’s manager, Gina Rodriguez, hired Davidson to get the post taken down. Davidson allows that he and Rodriguez had what Bove termed a "reciprocal referral relationship":

Q: She sends you some business?

A: Yes.

Q: Some clients?

A: Yes.

Q: And vice-versa; you send her some clients; right?

A: I think less so, but perhaps.

Q: Reciprocal, but a little bit one-sided?

A: I don't know.

In the first indication that this cross-examination is going to some strange places, Bove now precipitates the following exchange:

Q: You're still fairly close with Ms. Rodriguez; right?

A: Somewhat.

Q: I mean, you actually tried to represent her in connection with this investigation; right?

A: Well, I didn't try to. She was contacted by the District Attorney's Office. They wanted her to come in and give a statement. And I returned the call on her behalf as my client.

You are not misreading that. Davidson, the witness on the stand, also purports to represent another witness in the case. Bove goes on:

Q: The reason I used the word "try" is that you were instructed by the District Attorney's Office that they viewed that as a conflict because of your status as a witness; right?

A: Well, I took issue with that, but yes.

Q: You didn't necessarily agree, but that was the instruction?

A: I don't agree with the word "instruction." That was their --

Q: Position?

A: Position. That was their position.

Q: My point here was, the relationship with Rodriguez and you was close enough in 2023 that she still looked at you as someone that she still trusted to be her counsel?

A: True.

But things are only starting to get weird. And they still have a long way to go. Remember that cease-and-desist letter Davidson sent to TheDirty.com, the gossip blog that had an article from 2011 about the Daniels-Trump assignation? Bove elicits that Davidson did this work for Daniels without a retainer agreement and that he did some subsequent work on containing the spillage to other media outlets—also without a retainer agreement.

Was there ever an engagement agreement with Daniels? Yes, Davidson says, in 2016.

Hold on. Mega multi-front weirdness coming. Promise.

Bove now turns to the side letter to the deal in 2016. The word "decoded" was used, says Bove, with regard to the Peggy Peterson and David Dennison pseudonyms. These types of pseudonyms, the witness testifies, are "widely used with these types of agreements.”

Bove now asks about the Cohen call at the department store in which Cohen seemed "disheartened."

"I thought he was gonna kill himself," Davidson says with some concern. Cohen had thought he was going to be White House counsel or attorney general or something, and he was getting nothing.

And then, like that, Bove flips a switch and the weirdness begins.

“Now, I would like to take a step back and talk about, sort of, how you've interacted with law enforcement during the course of this investigation. Okay?”

“Fair,” Davidson responds.

How many times did Davidson meet with federal prosecutors in 2018? Three. Yet while Davidson’s meetings with McDougal and Daniels came up in those meetings, Bove suggests, Davidson didn’t seem as concerned with the attorney-client privilege as he is on the stand at trial now. Davidson does not bite. He doesn’t know how to answer this question, he says. Does Davidson recall invoking attorney-client privilege with federal prosecutors during three meetings in 2018? Yes.

Bove asks whether a few years later, Davidson met with the District Attorney’s Office. He did. Do you recall meeting with then-prosecutor Mark Pomerantz remotely by Zoom? He does.

And do you recall him saying that you’re obviously concerned with making a statement that someone is going to say—

Steinglass objects, and after a brief sidebar, Justice Merchan sustains the objection. The sidebar, we later learn, contains the following exchange:

THE COURT: What were you going to ask?

MR. BOVE: I was going to ask -- I'm summarizing whether he recalled Mr. Pomerantz saying he was choosing his words carefully because there was extortion inferred.

Extortion.

Oh.

STEINGLASS: So, let me see if I understand this correctly. What Mr. Bove is trying to elicit, one prosecutor expressed a view that seemed to suggest that that prosecutor believed that Mr. Davidson's conduct approached extortion, but then a subsequent person said, We're not looking at you for extortion, so the internal --

MR. BOVE: The same prosecutor.

THE COURT: Objection sustained.

Front Number 1 in the weirdness is now open, though the jury doesn’t know about it yet. That’s about to change.

You said that Cohen can be an “aggressive guy,” Bove says to Davidson, one aggressive guy to another. You can be an aggressive guy too, right? Davidson says he doesn’t know.

“What does the word ‘extortion’ mean to you?”

The audience is shocked. Davidson is not. “Extortion is the -- it's the obtaining of property by threat of fear or force,” he says.

It can be a state or federal crime, right? Yes.

Q: As you sit here today, is it your belief that any exposure that you have to State or Federal extortion crimes is excluded by the statute of limitations?”

A: I have no opinion.

Q: You're an attorney, and you have not thought about that prior to your testimony?

A: I have not.

When you were negotiating the McDougal and Daniels deals, didn’t you have to think about how to stay on the right side of extortion law? “Not particularly.”

Q: Well, one of the issues that you had to be sensitive about was not to threaten that the payment needed to be made prior to the election; correct?

A: I don't recall that.

Q: You were concerned about linking those two issues—payment, election—were concerned in written communications; right?

A: That was not my concern.

Q: Do you recall being asked about this issue in meetings in 2023 by the District Attorney's Office?

A: I do not.

Q: Do you recall a meeting where you indicated that you could not recall whether the thought of election as a deadline for getting stuff done had come up?

. . .

A: I remember saying I do not recall.

Q: And it's your testimony that you—even today, you don't remember whether or not you were concerned about linking the election in these payments?

A: Correct.

Bove approaches the matter from a different angle. You did media cases in that period, right? Yes. Those cases involve NDAs, right? Yes. So “in 2016, you were pretty well-versed in getting right up to the line without committing extortion; right?” Davidson says he doesn’t understand the question.

Bove is undeterred. You had “several representations that involved situations where you were making demands on third-parties on behalf of your clients; right?” Yes. You were asking for money and other benefits, right? Yes. “And you knew you had to be careful so as to not violate the law prohibiting extortion; right?”

“True,” responds Davidson.

And so in 2016, you had familiarized yourself with the law of extortion based on some very specific experience, right? No.

Bove drops his next bombshell: “Isn't it a fact that in connection with events in 2012, you were investigated by State and Federal authorities for committing extortion against Terry Bollea, Hulk Hogan?”

“That's true,” the witness acknowledges.

Weirdness Front Number Two is now open: Keith Davidson seems to be admitting that he was involved in the famous Hulk Hogan sex tape incident.

Bove goes on:

Q: And in connection with that investigation, did you or did you not familiarize yourself with the extortion offenses that were applicable in Florida and under Federal Law at the time?

A: That's fair.

Q: And so, getting back to my question, by 2016, you had, in fact, familiarized yourself with where that line was; right?

A: I had familiarized myself with the law. I'm a lawyer.

Q: And you did everything that you could to get as close to that line as possible in these negotiations without crossing it; right?

A: I did everything I could to make sure that my activities were lawful.

Q: And that included not making overt threats connected to the 2016 election; didn't it?

A: Threats to who?

Q: To Michael Cohen.

A: No.

Q: No? You made no threats to Michael Cohen relating to the 2016 election; is that the answer that you give?

A: I made no threats to anyone.

Q: You never linked these negotiations to the 2016 election with anyone; is that your testimony?

A: That's fair.

Weirdness Fronts Numbers Three through Twelve open in rapid succession.

- Bove asks Davidson about his role in getting a woman named Dawn Holland paid $10,000 for leaking confidential patient information from Lindsay Lohan’s drug treatment. Davidson evades the questions and can’t recall.

- Davidson concedes that he “believes” that in 2010 he helped broker the sale of a sex tape involving Tila Tequila. He worked on this deal with a guy named Kevin Black whom Bove describes as a “sex tape broker.” He testifies that he does not recall that his client in this deal was a man named Francis Hall, whom Bove describes as follows: “Do you recall that Mr. Hall, who also goes by Francis Thien, threatened Ms. Tequila that if she didn't pay him $75,000, the tape would be published?”

- Davidson also testifies that he doesn’t recall being on a 90-day bar suspension at the time of this deal.

- He also acknowledges that he represented several people who received money from Charlie Sheen. Bove describes this as “extraction” of money from Sheen, and Davidson resists the word: “There was no extraction.” But he does not resist the point: “We asserted that there was tortious activity committed and valid settlements that were executed.”

- He acknowledges that one of those cases involved a woman named Karen Montgomery, who was referred to him by the sex tape broker, Kevin Black. He testifies, however, that he does not recall that he got a 60 percent contingency fee from her, that—as Bove put it—“she had recently been under the influence of methamphetamine at the time you got her to sign the Engagement Letter,” that “she was barely completing sentences when you got her to sign the letter” or that Sheen paid $2 million to settle the matter. Asked whether his memory is weirdly fuzzy on a $2 million payout, Davidson says he has had more than 1,500 clients over the course of his career and that he doesn’t remember a settlement from 13 years ago.

- He acknowledges that he represented a woman named Capri Anderson but refuses to discuss her settlement with Sheen. Why this settlement is different from all other settlements is unclear. He once again resists the term “extraction” from Bove and says that “assuming arguendo that he did pay and there was a Settlement Agreement, that settlement would be confidential, and I would not discuss it here.” After a brief sidebar with Justice Merchan, Bove he’s not “not asking you to assume anything. I'm just asking for truthful answers. Okay?” "I am giving you truthful answers, SIR," Davidson says, with a noticeable emphasis on the word “sir.” “And if you're not here to play legal games, then don't say ‘extract.’” A reporter in the press room says: "Now this is an exchange!”

- Davidson testifies that he had nothing to do with getting still images from the Hulk Hogan sex tape posted in 2012 on TheDirty.com, the same website that the previous year he had gotten the Daniels material removed from. And while he recalls reaching out to Hogan’s representatives that year, he has no recollection, he testifies, of telling them that the reporting on the sex tape by Gawker was a “shot across the bow.” He has no recollection of telling Hogan’s representatives that he was an expert at this kind of thing. And he has no recollection of telling Cohen about this interaction in 2018—until, that is, Bove shows him text messages that refresh his recollection on this latter point. Even then, he professes to have no recollection of telling Hogan’s representatives: “We got a lot of people, they get caught on tape. They're not all celebrities. We have family men that are gay, and they want to keep their gay identity undercover, so we approach them, too.” He has no recollection of demanding a million dollars from Hogan, though he acknowledges that there was a “monetary demand made” for purchase of the tapes. And he has no recollection—again, until his memory is refreshed—of the National Enquirer publishing information about the tapes in 2015. He denies that Dylan Howard has a byline on the story because, as Bove puts it, “you referred this information to him.”

- He acknowledges that there was an FBI investigation of this matter. He also acknowledges that the FBI ran a sting operation targeting a meeting between Davidson and Hogan's representatives at a hotel. Agents recorded the meeting, while sitting nearby.

- He also acknowledges that the Tampa Police Department investigated the matter and issued a report referencing concerns about extortion. Though Davidson was not ultimately charged, Bove suggests that his experience with the Hogan matter gave him familiarity with extortion law. Perhaps, Davidson allows, I don’t know.

- Finally, Bove “extracts” from Davidson a quick discussion about Gabriel Rueda, who felt he was owed a $100 million finder's fee related to a fight between the boxers Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather. Davidson instead offered him a settlement for considerably less money. Davidson denies, however, that he told Rueda—as Bove puts it—that he was “dealing with powerful people who did not care if Rueda got hurt” and “threatened he would not be able to find work in California if he did not accept” the settlement.

We now turn back to one of the celebrities directly involved in the current case—McDougal—and one of her former friends who, according to Davidson, was attempting to publicize in June 2016 her prior “interactions” with Trump.

As Bove confirms Davidson's fee for representing McDougal (45 percent), we turn to People’s Exhibit 279, which we saw on Tuesday, an email from Davidson to McDougal regarding the retainer agreement, with Jay Grdina bcc’d.

After a truly salacious period of time name-checking a who’s who of mid-2010s tabloid celebrities, the pace—and tension—slows. We’re reviewing documents once again, including agreements, texts, the details of which Davidson often can't recall.

We see texts between Dylan Howard and Davidson dated June 7, 2016, displayed on screen.

“I have a blockbuster Trump story” Davidson texted Howard.

Bove begins a line of questioning to get Davidson to say that in this case and many, his relationship with the National Enquirer benefited his law practice, but Davidson resists. “Maybe, or maybe not,” he says. “Perhaps.”

In any case, the story stalled after Howard could not find enough corroborating information.

“Is this a good time to stop?” Merchan asks, as members of the press yell “YES” silently in their heads.

We break for lunch.

* * *

Our ever-punctual judge is back on the bench at 2:12 p.m., slightly ahead of schedule.

Before the witness retakes the stand, Necheles raises an issue about the gag order, as she hands up a pile of articles by legal commentators. The articles, which Trump wants to post on Truth Social, discuss the case and witnesses who testified, so she wants to run them by the judge first because of “ambiguity in the gag order.”

Steinglass finds it odd that the defense is asking the court for an advanced ruling, adding that the gag order is “very specific.”

Justice Merchan appreciates Necheles bringing these to his attention, but sides with the prosecution here: He’s not going to give an advanced ruling.

“There is no ambiguity in the order,” he says. “At this point, this court and the higher court have found there is nothing wrong with the gag order.” He would advise Trump, “when in doubt, steer clear.” Necheles pushes back, but Merchan cuts in—“I’m not going to argue this with you, Ms. Necheles.”

Necheles persists, but Merchan repeats himself: "When in doubt, steer clear." She relents, and takes a seat.

* * *

The jurors are back, and Davidson is once again at the stand, putting on a brave face. The pre-lunch cross was something fierce.

Bove takes the lectern again, and begins with the 2011 blog post on TheDirty.com, Gina Rodriguez (Daniels’s longtime manager), Rodriguez’s boyfriend Anthony Kotsev, and James Grdina, McDougal's ex-husband.

The weirdness begins anew.

Didn't Kotsev write that blog post? Davidson doesn't know.

And wasn’t TheDirty.com owned by Grdina? Again, Davidson can't recall.

Bove stops abruptly to lean down and collect something that fell. “That drop was catastrophic to my binder,” Bove says, reshuffling the documents before him.

Perhaps he had a heavy lunch. The atmosphere is lethargic, even as the material is once again fabulous. Bove seems to be suggesting that the people around Daniels arranged to have TheDirty.com publish the article and then hired a lawyer (the witness) to force them to take it down.

Bove resumes, asking whether Daniels and McDougal wanted the blog post taken down so that they could negotiate a better deal through Davidson. Not exactly. “They were using my efforts to create an exclusive opportunity with a different publication,” Davidson clarifies, pinching the air. Sounds like a yes, but Bove lives with the answer.

We move to Cohen, with whom Davidson continued to work after the Daniels settlement. Bove asks whether Davidson recalls saying to Cohen on March 7, 2018: “Sometimes people get settler's remorse, you know, and other times people think that, hey, I need to resolve this case before a date certain because this is when I have the most?”

Davidson doesn’t recall, so Bove introduces Defense Exhibit F15-AT, and instructs Davidson to don a set of headphones, which he holds up to one ear at first like a radio DJ. He takes them off and puts them on again upside-down, which would still “technically” work, to borrow a word from Davidson.

Conroy also has headphones on now, as does Necheles. It looks a bit like the lamest silent disco you’ve ever seen, which is saying something.

The audio has refreshed Davidson's memory. He confirms saying the above to Cohen, who had recorded the conversation.

Elsewhere in the transcript, Bove points to Davidson’s phrase “hypothetically speaking” and asks whether that was code. “You were using the word ‘hypothetical,’ so you could sit in a chair like this and say, ‘I'm not sure if I was talking about Stormy Daniels?’” Bove accuses Davidson, his voice rising.

Davidson agrees that this conversation was about Daniels but tells Bove he is “grossly mistaken” about the dates.

But Bove presses on: This is all shorthand for “settler's remorse,” is it not?

That's true, Davidson relents.

Bove asks Davidson his recollection of another conversation with Cohen in which he says Michael Avenatti has really driven a wedge between Daniels and Rodriguez. Davidson can't recall, so he puts the headphones back on, and the lame silent disco resumes. The clunky headphones are connected to dials that resemble a Walkman, so the scene has a real throwback quality to it. Trump’s eyes remain closed. Perhaps his own silent disco is playing in his head.

Bove reads a transcript of a conversation between Cohen and Davidson during which the latter said to the former: “I wouldn't be the least bit surprised if he comes out and says, you know what, Stormy Daniels, she wanted this money more than you could ever imagine. I remember hearing her on the phone saying: You fucking, Keith Davidson, you better settle this God damn story because if he loses this election, and he is going to lose, if he loses this election, we all lose all fucking leverage. This case is worth zero.”

“Nothing further judge,” Bove says at 2:55 p.m.

Steinglass asks for a 5-minute break, which Merchan grants, before redirect.

* * *

At 3:03 p.m., Steinglass is back at the lectern, clarifying that Avenatti was suing Davidson and Cohen at the time Davidson said Avenatti was driving a wedge between Daniels and Rodriguez.

Steinglass clarifies that the comment about leverage after the election, which Davidson had initially attributed to Daniels, were actually things Kotsev was going to say.

Next, Steinglass displays People's Exhibit 267, pages 10 to 11, while he plays People’s 265, from 11m13s to 13m33s. It's the first time today we hear Cohen's actual voice. The recording is crystal clear, at least on Cohen's side, clearer even than the audio from the overflow feed of people speaking in the courtroom.

Cohen: What would you do if you were me?

Davidson: Ugh. I can't even -- I don't even know. (Inaudible) I can't even imagine. So --

Cohen: I mean, would you write a book, would you break away from the entire Trump, you know, we'll call it doctrine, you know, would you go completely rogue, would you join with Bannon, you know. What -- I mean any -- any thoughts? Because it’s not just me that’s now being affected. It is my entire family. It's, you know -- and the -– there’s no -- nobody is thinking about Michael. You understand? And despite what like -- for example, you know, what the earlier conversation, you know, and who else would do that for somebody, who else?

That's it for Steinglass, and Bove steps up to take another bite at the apple.

Davidson isn't sure of the date of the conversation, a fact which Bove uses to call into question his frame of reference for it.

As the day grinds on, Trump continues to sit motionless. At this point, he has almost blended into the furniture.

Bove offers more clips—F15-A, F17-A, F17-C, and F17-E—along with their corresponding transcripts.

The first F15-A, is the conversation between Davidson and Cohen, in which the former says “hypothetically speaking ... sometimes people get settler's remorse.”

In that clip and each successive one, the voice is clearly Davidson’s, but the tone and swagger of Davidson on the phone is a far cry from Davidson on the stand.

At 3:23 p.m., nothing further from Bove, nor Steinglass, and Davidson steps down.

“People, please call your next witness,” Justice Merchan says.

* * *

The People call Douglas Daus. He walks up to the stand wearing a dark suit and dark shirt, with a bright tie.

Daus works for the New York County District Attorney's Office’s High Technology Analysis Unit (HTAU). The unit, at which he has worked for 10 years, processes digital evidence and produces reports from the extractions.

Daus first recounts his CV, including a stint embedded with the U.S. military in Iraq, doing “the same type of work” as he does here.

As a supervising computer forensic analyst with HTAU, which means that when the DA’s office gets a device that is a computer or phone, he processes that device, takes a digital copy of it, preserves it, and then analyzes it.

Daus walks through the process of extracting and analyzing evidence from devices, mostly phones, and estimates that he has analyzed 3,392 devices up to this day.

Conroy: Approximately?

Approximately, answers Daus.

What kinds of data can be extracted from a smartphone? Texts, software, call history, log files, anything that is normally on a phone.

Contact lists? Yes. Pictures? Yes. Calendar entries? Yes. Associated phone number? Yes. Username? Yes. Emails? Yes. Downloaded apps? Yes.

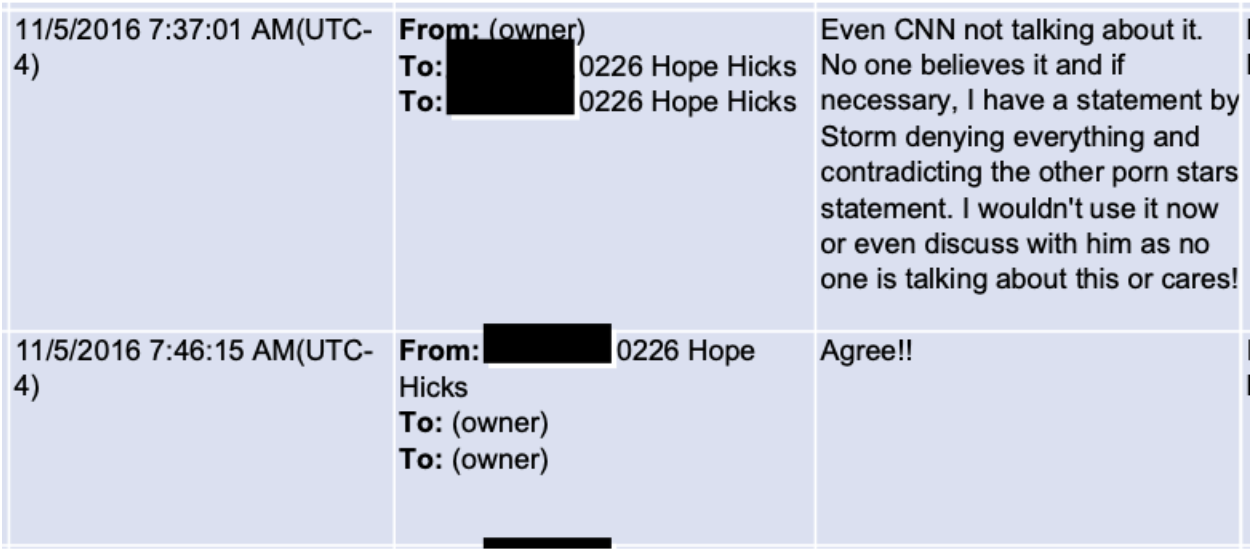

Daus was assigned to the Trump investigation and analyzed two devices belonging to Michael Cohen—an iPhone 6s and iPhone 7. (0114 was the last four digits of the phone number for the iPhone 6s, and 6866 for the iPhone 7, if you must know.) Daus says that Cohen consented at the time to the data extraction, granting HTAU entry to his phones by giving them his passwords.

We will spare you some of the gory details here, like whether Cohen’s phones were powered on or powered off when they arrived for forensic analysis. With no fault to Mr. Daus, his testimony could not exactly be called riveting so far.

Conroy introduces a slew of exhibits into evidence, without objection: People's 246, 247, 249-254, 256-264, and 266. They’re text messages that include Cohen.

The first text is from Cohen to Hope Hicks: “Call me”—perhaps a clue as to the prosecution’s next substantive witness.

We now hear the full number of contacts in one of Cohen's phones: 39,745.

“Is that unusual?” asks Conroy.

“That is unusual,” says Daus, who usually sees phones with contacts in the hundreds.

Unusual perhaps, but probably the appropriate amount of contacts you’d want in a fixer. At an impressive near 40,000, Cohen was quite the man about town.

We see some of those contacts (with sensitive information redacted): three pages of contacts for David Pecker; two for Hope Hicks; 12 for Allen Weisselberg; and 10 for Donald Trump. Dylan Howard is also there. So is Keith Davidson. Keith Schiller, Melania Trump, Rhona Graff, Jay Sekulow, Larry Rosen, Daniel Rotstein, and Gary Farro.

Cohen’s other phone boasts a more “normal” 382 contacts.

The next evidence on screen is a photo of Cohen, pulled off of his own phone, beaming at a podium with the White House seal behind him. Daus doesn’t know Cohen but says he recognizes him in the photo because, “I watch a lotta news.”

The metadata suggests the beaming Cohen photo at the White House was created on Feb. 8, 2017, at approximately 5:39 p.m. Another piece of evidence shows a calendar entry from Cohen's phone called "Meeting with POTUS" for the same date.

After a bit more voyeuristic snooping through Cohen’s phone, we’re done for the day.

Someone once described warfare as long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror. This day in court had elements of that: long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of outrage and hilarity.

May 3, 2024

When we left off yesterday, Doug Daus—a forensics expert with the Manhattan District Attorney's Office—was on the stand, testifying about evidence recovered from Michael Cohen's phones. His direct examination had seemed straightforward enough: He received two phones, which Cohen had shared voluntarily. He processed the phones. He recovered a bunch of stuff, most particularly an audio recording of Trump discussing the payoff of Karen McDougal with Cohen.

On cross-examination, however, Trump defense attorney Emil Bove seemed intent on making the matter of the exploitation of these phones more complicated. He questioned Daus about the chain of custody of Cohen’s phones, for example. He seemed to be implying that the data on the phones might have been altered or compromised. It was unclear where he was going with this.

We’re going to find out today.

Justice Merchan, our silver-haired and always-timely presiding judge, sweeps into the room at 9:30 a.m. on the dot—resplendent in his robes and all that jazz.

He begins with a clarification, prompted by Trump’s statements to reporters outside of court yesterday, in which he said that the court’s gag order meant that he’s “not allowed to testify” at trial.

That’s why Justice Merchan starts by explaining that there seems to be some confusion as to whether the gag order limits Trump’s right to testify in his own defense. Mr. Trump, he says—addressing the defendant directly—you have an absolute right to testify at trial. A right to testify, and a right not to testify. The gag order does not restrict that right to testify, Justice Merchan explains.

Merchan explains that the gag order only applies to extrajudicial statements—meaning statements made outside the courtroom.

Please let your attorney know if you have any lingering doubts, he instructs the former president turned criminal defendant.

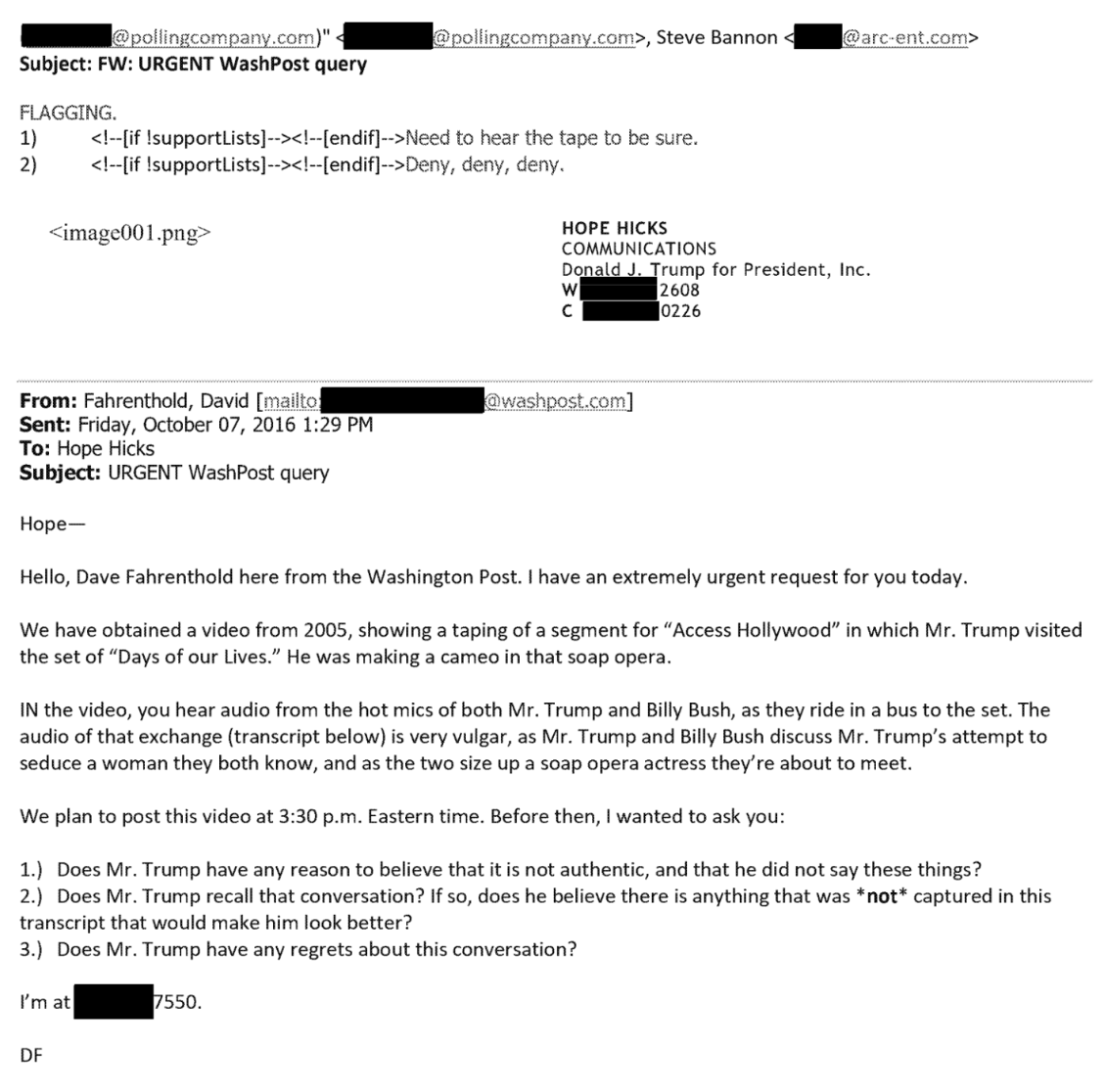

With that behind him, the parties discuss some lingering evidentiary issues: Can the prosecution admit a Washington Post article and tweet about the "Access Hollywood" tape? Justice Merchan has previously ruled that the Hollywood tape couldn't come in but that the text of it could.

But prosecutors now want to introduce the Washington Post story’s about the tape as evidence in order to establish the date and time on which the tape was published. The trouble is that at least one exhibit includes a picture of Trump. And Justice Merchan thinks that should be verboten under the same logic as his earlier ruling.

I don’t want the words spoken on that tape to be associated with his face or voice, Justice Merchan explains. It’s powerful evidence, he says.

Prosecutors say that they'd be happy to stipulate to the date and time of publication—if the defense counsel would agree to that stipulation.

Alternatively, the prosecution suggests blotting out the picture on the exhibit.

Merchan, anxious not to keep jurors waiting, says he'll let the parties work it out.

Now the witness, followed soon after by the jurors, file into the room.

* * *

The witness, Daus, is wearing a tan suit and glasses.

Bove, on behalf of Trump, rises to resume his cross-examination.

Bove picks up with a line of questioning he ended on yesterday: The chain of custody for Cohen's phones.

The cross-examination is long and tedious and involves a series of highly technical inquiries about metadata and laptop syncing and forensic data extraction. But it is all geared toward showing that the data extracted from the phone could have been manipulated by Cohen. And as Bove reaches the end of his cross-examination, he brings it home effectively.

He gets Daus over the course of the cross-examination to concede the following. Cohen’s two phones were turned over voluntarily, not seized, so there was no element of surprise. Four days then pass until the person who had them turned them over for processing.

So there’s a gap there, Bove suggests, and Daus does not disagree. And from a forensic perspective, the lawyer goes on, that’s not ideal, because we don’t know what happened to the data during that period. Daus assents.

And then when it’s turned over again, there’s only one signature, not two, Bove notes. Daus agrees. That’s not standard either, Bove asks, is it? Sometimes, Daus says blandly, as though he’s seen a lot of variability in his day in how these things are done.

Bove pushes. The reason is to avoid a situation in which there’s a dispute between the recipient and the person who turned over the phone. You want to have a third-party witness, right? Ideally, Daus concedes.

And we don’t have that here? We don’t.

We don’t know if the phone was powered on or off, during that time, or whether it was in a Faraday bag, or whether it was hooked up to the internet, right? Daus seems less impressed by these facts than Bove, but he has no dispute on the facts.

This goes on for a while and Bove extracts—pun very much intended—some additional concessions:

- Cohen was using several apps that delete his messages quickly.

- One of the phones had undergone a factory reset at one point, raising questions about the date of the audio file.

- One of the phones had been synced with computers more than once.

- The audio file cuts off before the file is over.

In other words, Bove suggests, you would have to take Cohen’s word about the reliability of the evidence contained on his phone, right? Daus cheerfully concedes the point.

You would have to take Cohen’s word about the phone’s syncing history, right? It seems so.

The phone has some oddity about the audio file, and you’d have to take Cohen’s word about that right? Yes.

There’s a syncing history you’d have to take Cohen’s word about too, right? Yes.

The phone was powered on and off and actually used at one point while it was in the DA’s custody? Yes.

And there’s missing stuff from the audio file? Yes.

All of this is far from ideal if you’re trying to figure out what this phone was doing in 2016, Bove suggests. This phone has been synced multiple times, turned on and off, and this raises questions from your perspective? This is far from ideal in a forensic sense if you’re trying to figure out what happened? Daus readily assents.

The things I’ve showed you this morning raise some questions about how this phone was handled? Yes, Daus replies.

And in any case, we’re going to have to take Cohen’s word for it, right? Yes.

Bove has had a very good cross-examination, though a lot of the press corps died of boredom during it. He has successfully gotten the government’s technical expert to admit that if the jury doesn’t trust Cohen, they shouldn’t trust implicitly what was pulled from his phone either.

On redirect, Conroy controls the damage.

You’re not a friend of Cohen’s, are you? No.

Is it unusual for a phone to be turned off and on? No.

Is it unusual for a phone to be used to make recordings? No.

There are other recordings made on that phone, but those not at issue here, right? Correct.

And to the extent there are call records not reflected on the phone, those can be verified by cross-referencing them to the toll records from the service provider, right? That’s the best source.

Conroy asks about the difference between voluntary production and operating under a search warrant. They are quite different forensically, Daus says, because when you do it by consent, you do the extraction with the code or password given by the user, so you can generally do a full forensic extraction. With a search warrant, you may not have the code, and you thus have to forcibly extract the data.

Were able to do full forensic extraction? Yes.

And that’s the gold standard, right? Yes.

Did you detect any evidence of tampering or manipulation on any of the data that you pulled related to any of these exhibits? I did not.

Conroy is done, and Bove is back up. You observed no evidence of tampering, he notes, but my questions are more about the unknowns. They are about whether you saw gaps in the handling of the data that created risks of tampering. Daus concedes that he did.

Can we agree that the recording cuts off mid-conversation? Yes.

And that we don’t know what happened after the cutoff? Yes.

And that someone has told you about a phone call that caused the cutoff in the recording? Yes.

And that there’s no record of that call on the device itself? Yes.

And they say get the toll record to verify the call? Yes.

And why is this toll data not reflected on the phone? We don’t know, right? Yes.

Bove is done. Again, his only point here is to leave in the jury’s mind that there were opportunities for Cohen to manipulate the data. He will presumably take up with Cohen whether he actually did so later.

Conroy offers only the briefest of redirects. If I made a call seven years ago, he asks, would you expect to see a record of that on my phone today? No.

We are done with Mr. Daus.

* * *

With that, the People call the next prosecution witness, and it’s one of their own. Georgia Longstreet is a paralegal who works for the Manhattan District Attorney's Office and who has worked on the People of New York v. Donald J. Trump case. She is by far the witness so far more likely to work for Lawfare as a student contributor than to be mixed up with Donald Trump, David Pecker, Dylan Howard, and Michael Cohen.

Longstreet is a young woman—she appears to be in her 20s—with light brown hair. She’s wearing a navy suit. She’s here to get stuff related to Hope Hicks into the record, again providing strong indication that Hicks is going to be our next major witness.

On direct examination by the prosecution, Longstreet discusses her work on the Trump case.

In brief, Longstreet is the Trump social media monitor-in-chief for the Manhattan District Attorney's Office. In that capacity, she locates public records relevant to the case. She has been assigned to the Trump case for about a year and a half. She saves social media posts and news articles relevant to case. Her process for doing so is, in effect, to screenshot the relevant material and then save to a folder with a few words about what the document is. Then she hashes the screenshot, which is to say cryptologically time-stamps it, so that she can verify reliably when she collected and logged it.

As a part of her work on the case, she reviews Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Truth Social posts from accounts related to the case multiple times a day. In some instances related to her instant testimony, she used the Wayback Machine to recover old posts.

As Longstreet discusses her work reviewing thousands of social media posts by Donald Trump and his associates every single day, we all think what a weird job that is!

Then we realize that she is actually describing our jobs. The argument for her coming to work for Lawfare gets better and better.

Rebecca Mangold, on behalf of the prosecution, wraps up her direct examination by moving to admit some exhibits of material that Longstreet has collected.

Blanche objects to admitting the exhibits, citing hearsay.

Justice Merchan instructs the jurors to take their morning break. He wants the parties to take a few minutes to discuss Blanche's objections and try to work out a stipulation.

The parties confer. When they return, the prosecution says that it will withdraw its motion to admit the article about the "Access Hollywood" tape. The defense has agreed to stipulate to the date and time of the tape’s publication.

As for the other exhibits—many of which seem to be social media posts by Trump or others—Justice Merchan overrules Blanche's hearsay objections. He explains that he finds Longstreet’s process of monitoring, screenshotting, and hashing the relevant content to be reliable.

The jurors return.

Mangold, for the prosecution, reads the stipulation into the record: “The parties have stipulated that the Access Hollywood tape referred to during this trial was publicly released by The Washington Post on October 7, 21 2016, at 4:01 p.m., Eastern Standard Time. The article was authored by David Fahrenthold.”

With the exhibits now admitted into evidence, Mangold instructs the witness to read the content of the exhibits.

The exhibit is an apology video posted by Trump following the publication of the "Access Hollywood" tape.

"Anyone who knows me knows this doesn't reflect who I am," Trump says in the video.

"I said it, I was wrong, and I apologize."

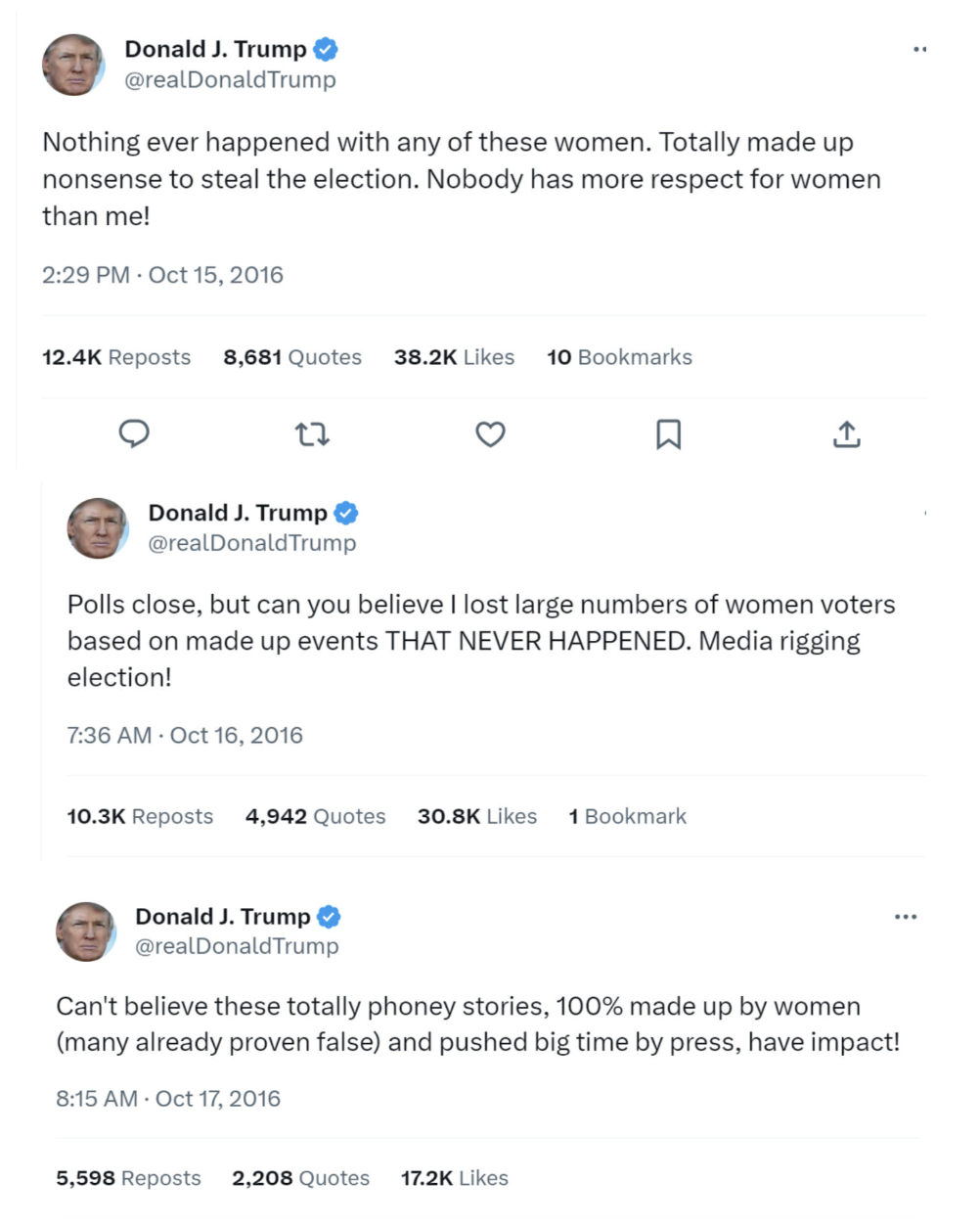

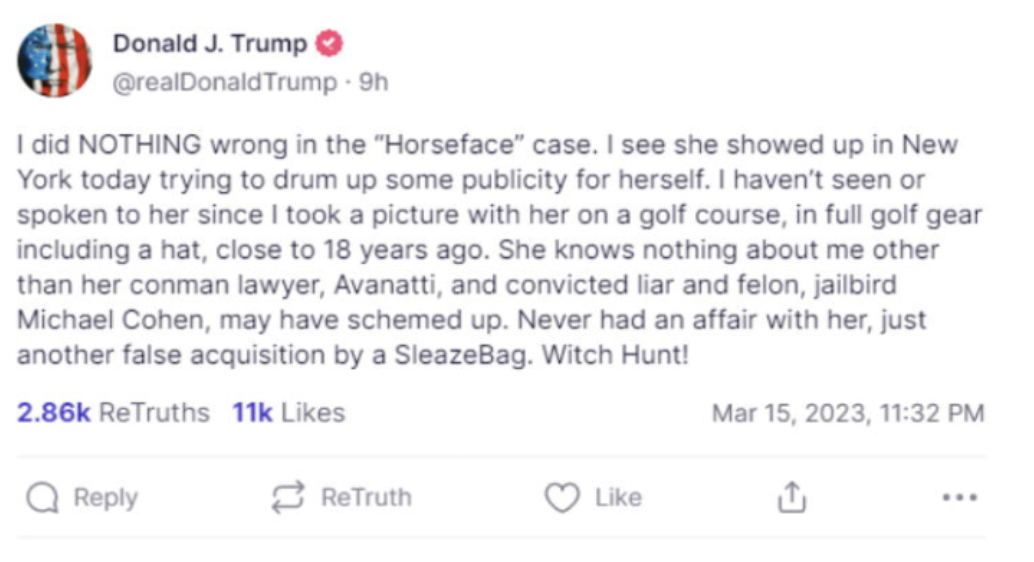

Other social media posts admitted into evidence involve Trump denying certain allegations about his conduct with women:

The final exhibit admitted into evidence is Trump's now-infamous post on Truth Social in which he declares "IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I'M COMING AFTER YOU."

Blanche pops up for a brief cross examination. He clarifies that Longstreet reviews accounts as instructed by prosecutors, not as a result of her own research instincts.

Was one of the accounts she tracked Michael Cohen’s Twitter account? Yes. What about his podcast, Mea Culpa? Yes, she followed that too.

Have you listened to all of them? “Absolutely not,” she says with emphasis.

Laughter from the press.

How did you determine which ones to listen to? Some were more obviously relevant than others, and some were by instruction from the lawyers.

How many thousands or tens of thousands of social media posts did you review? I couldn’t give an exact answer between 5,000 and 10,000 since December 2022.

And of all the thousands of social media posts and podcasts you reviewed, Bove asks, did you decide which seven to share today? Longstreet grins. “I’m just a paralegal. I apologize.”

So the prosecutors did that? Yes.

You have no independent knowledge, he asks, of who wrote a given ”truth” or tweet, right? Correct, Longstreet says. She only knows whose account it was posted to.

And you have no independent knowledge about why a post was made? Right, Longstreet agrees.

That’s it. Longstreet is dismissed and rejoins her colleagues on the prosecution side of the courtroom. At the end of the day, she will be responsible for wheeling out the giant cart full of binders the lawyers use.

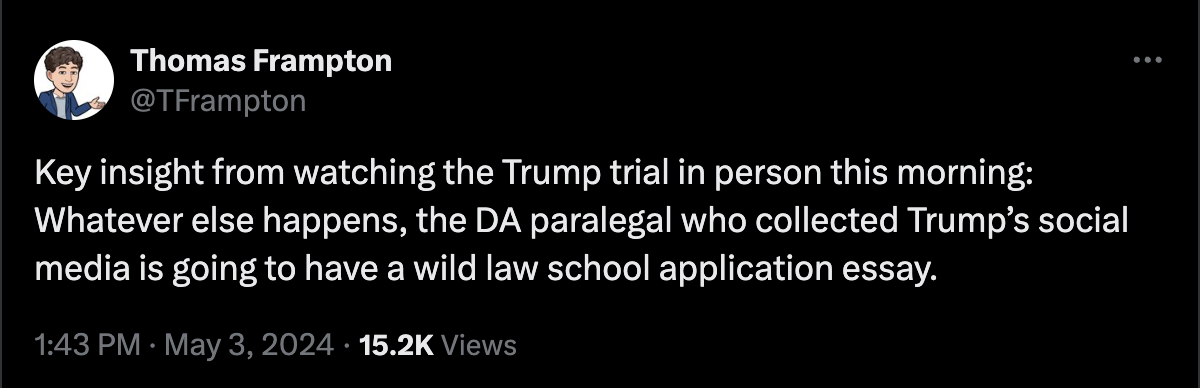

As one wag wrote on Twitter, she’s going to have a mighty-fine law school admissions essay:

* * *

Longstreet is done, and the People call their next witness: Hope Hicks, the former White House communications director.

Hicks is sworn in. At first, it's hard to hear her responses to basic biographical questions. She has to adjust the microphone.

She's apologetic. "I'm nervous," she explains.

She has reason to be. Hicks has built herself a respectable career after leaving the White House. She is one of the few Trump loyalists who is not persona non grata in polite society. She has also never betrayed Trump, across from whom she is now sitting and about whose conduct she is now answering questions. Whatever one thinks of her choices in life, she’s in a tough spot—an emotionally wrenching one. And unlike Pecker, she is not a cold-blooded reptile who collects and dishes dirt on celebrities for a living.

Hicks says she's here under subpoena, and she is represented by counsel. She's paying for her legal representation herself.

Ouch.

Trump is not a current client for the crisis communications firm where she now works, she says. They have no current relationship.

Her last communications with Trump were in the summer or fall of 2022.

Left unsaid, her entire career is a function of her work for Trump, and she’s clearly fond of him.

Hicks began working for the Trump Organization in 2014, she says. As director of communications for the Trump Organization, she worked on public relations and marketing. Eventually her work transitioned to political work for Trump as he shifted over into serious contemplation of a presidential run in 2015.

At the Trump Organization, Hicks spoke regularly with Trump. She ultimately started talking to him every day, as she became more essential and as his profile increased in politics.

She reported directly to Trump, she says. Everyone who works there reported to Trump, she explains. It's a big and successful business, but it runs like a small family business. So people reported to the family members, including Don Jr., Eric, and Ivanka.

Matthew Colangelo, handling the direct for the prosecution, now asks her about other key personnel—presumably witnesses we are going to hear from—in the Trump Organization.

Keith Schiller, she says, was Trump’s bodyguard. He would attend events with us and served as a security liaison at big public events. There was a “close relationship” between Schiller and Trump, she says.

Rhona Graff, who testified earlier, was Trump’s executive assistant. She was crucial to how everything ran on the 26th floor of Trump Tower. She had a lot of knowledge about Trump’s likes and dislikes, the business, his contacts, and that sort of thing. She helped facilitate media relationships. Her relationship with Trump? It was “one of mutual respect.”

What about Allen Weisselberg? He was the chief financial officer of the Trump Organization. Hicks worked with him during her time there, she says. He was involved in anything that had to do with money. During the time when Trump began his campaign, for example, Weisselberg was helpful with things like Trump’s personal finance disclosure document. He was also helpful on things like loans to the campaign for what was supposed to be a self-financed campaign.

His relationship with Trump? “Also one of mutual respect.” Weisselberg had been a long-time employee of the Trump Organization. “He had a lot of institutional knowledge.” And he, too, reported directly to Trump.

Colangelo now comes to Cohen. Hicks says that Cohen worked there when she started, but that she believes they met before that. She says he was an attorney but that she was not specifically clear on what precise type of work he did. She knows, however, that he was involved in the company’s entertainment deals—things like the Miss Universe pageant.

Hicks eventually began to work for Trump's campaign for president. One day, Trump said, "We're going to Iowa."

"I didn't really know why," Hicks says with a laugh.

But after Iowa, it became clear that Trump had his sights set on political office. And then, in June 2015, Trump announced his run for the presidency.

"Eventually, I just started spending so much time working on the campaign [that] I became a member of the campaign, and I was the press secretary."

During the campaign, Hicks spoke to Trump every day, often multiple times a day.

Trump was "very involved" in media strategy, she testifies. He was responsible for overall messaging. "We were all just following his lead. He deserves the credit for the different messages that the campaign focused on."

Hicks says that she would check with Trump before making statements on behalf of the campaign.

During the campaign, Hicks traveled with Trump frequently. Keith Schiller, Trump's bodyguard, also traveled with Trump. If someone wanted to reach Trump during the campaign, Schiller could be useful in facilitating access to Trump.

Hicks testifies that she knows David Pecker, the former publisher of the National Enquirer who testified last week.

She was introduced to him in a previous job, before she joined the Trump Organization. She reconnected with him at some point as he was a "friend" of Trump.

Were you ever present for phone calls between Pecker and Trump during campaign? Yes, Hicks says.

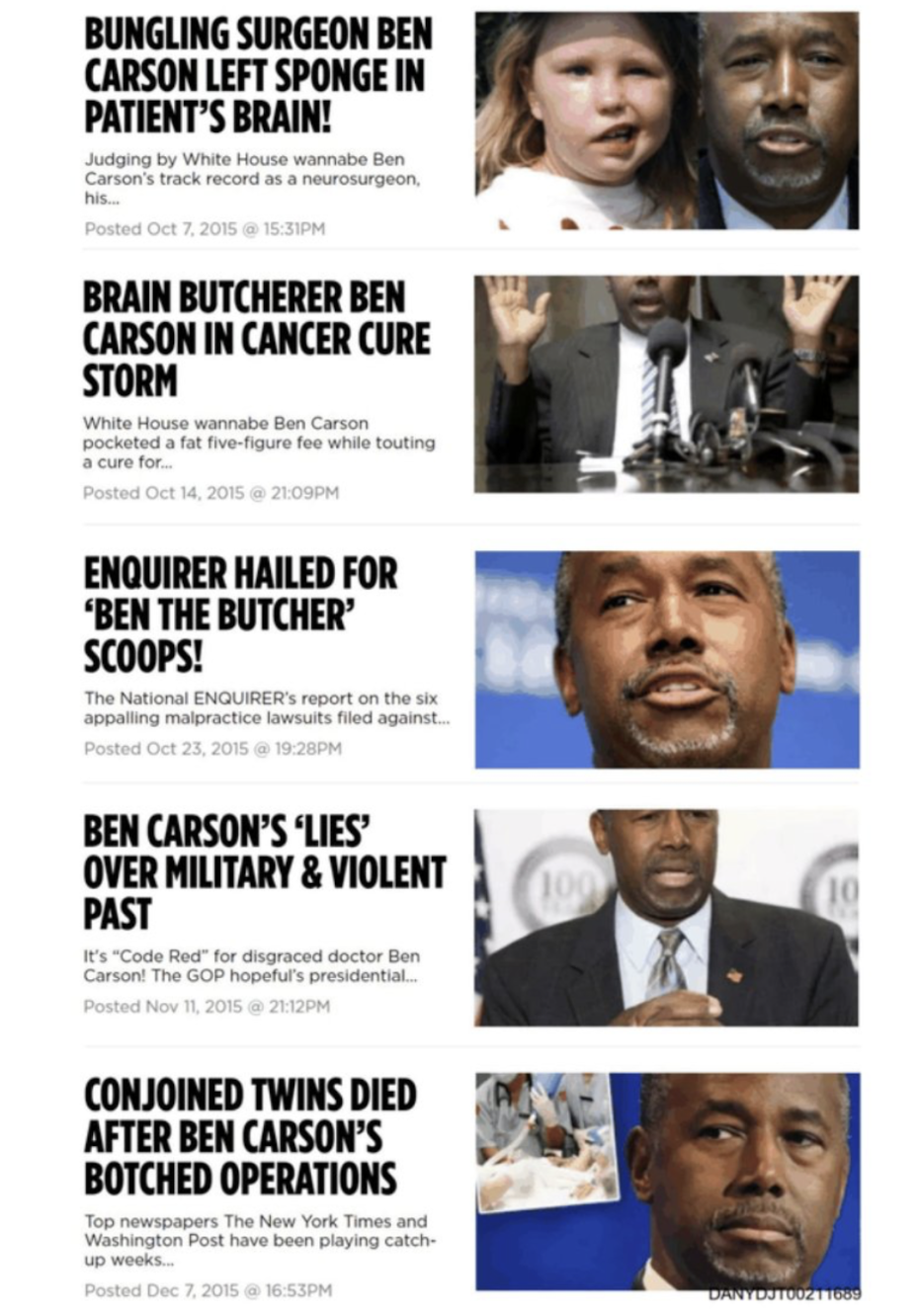

Specifically, Hicks overheard a conversation between Pecker and Trump about an article the National Enquirer published about Ben Carson related to medical malpractice.

"He was congratulating David about a great investigative piece," Hicks says.

She vaguely recalls him saying to Pecker: "This is Pulitzer worthy."

Big laughs in the press room.

A sample of the Enquirer's Pulitzer Prize-worthy Ben Carson coverage:

Colangelo asks Hicks if she recalls ever being present for a meeting between Pecker and Trump at Trump Tower.

Hicks says she does not have a specific recollection of that.

Now Colangelo, on behalf of the prosecution, moves on to the events surrounding the publication of the "Access Hollywood" tape approximately one month before the 2016 election.