If Facebook and Google Are State Actors, What’s Next for Content Moderation?

The pivotal question, doctrinally, turns out to be what kind of First Amendment forums Google and Facebook operate.

I argued previously that Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, in combination with intense congressional pressure, has turned internet mega-platforms like YouTube and Facebook into state actors when they censor content they deem objectionable. But this is only the beginning of the constitutional analysis. Figuring out what the right constitutional rules are is much harder.

The rise of online social media—disseminating information, entertainment and opinion at levels unprecedented in all of history and massively dominated by a few big-tech giants—is constitutionally unknown terrain. Legal solutions arrived at for other media probably won’t translate well, and new constitutional doctrine will eventually be required. But I’m not going to propose new theories or new constitutional frameworks here. The question I address is what courts should do under current doctrine.

Under existing law, some categories of speech are said to enjoy no constitutional protection: perjury, for example, or libel, obscenity, incitement to riot, and offers to sell illegal goods. People can go to jail for these speech acts notwithstanding the First Amendment. Outside the limited unprotected categories, however, all other speech is considered protected. So if Google and Facebook are state actors when blocking content they deem objectionable, a first thought one might have is that they can continue to filter out unprotected speech but must stop censoring protected speech. In other words, they can exclude unlawful content but must allow everything else.

Things aren’t so simple. In reality, even under existing law, so-called unprotected speech is protected in important ways—for example, by the bar on prior restraints—while state actors can, in a variety of contexts, regulate or even prohibit protected speech. The pivotal question, doctrinally, turns out to be what kind of First Amendment forums Google and Facebook operate.

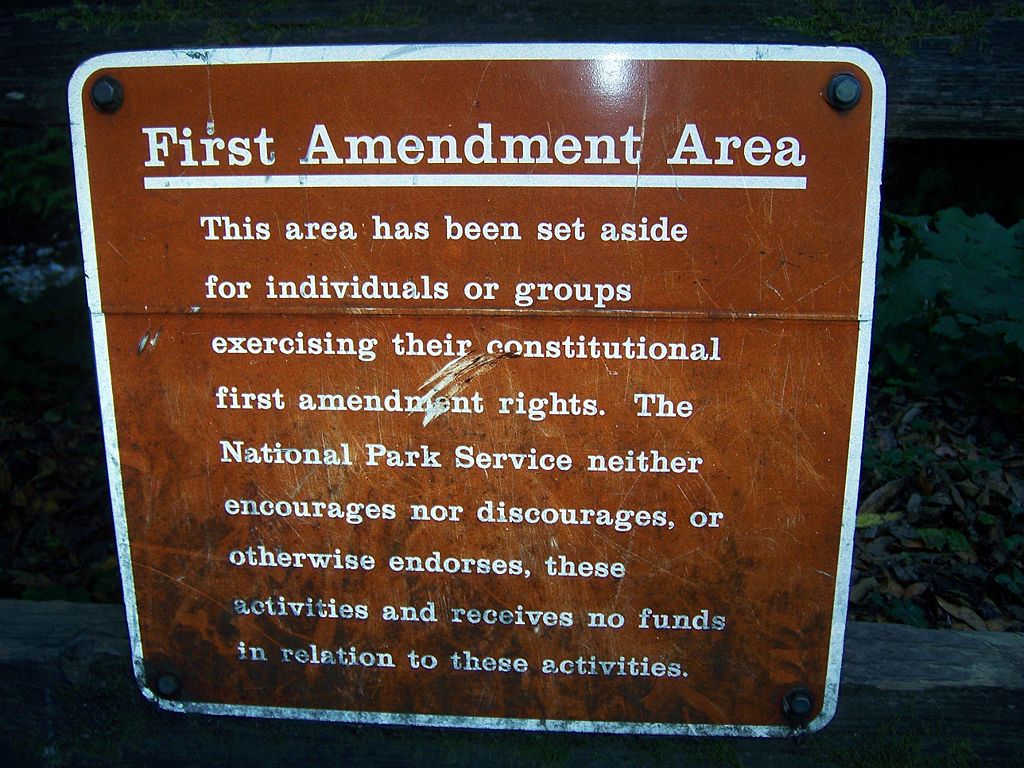

The freedom of speech has never meant that you can say whatever you want wherever you want; different rules apply in different places. Current doctrine deals with this problem through the so-called “public forum” doctrine. In places like streets or parks, free speech rights operate at full strength. Such spaces are called “public forums,” defined as government-owned areas that have been open “from time out of mind,” or deliberately opened up, to everyone to express their opinions as they choose. In public forums, while unprotected speech can be criminalized, the accepted rule is that for all other speech, any effort by state actors to restrict what people can say on the basis of its content—that is, on the basis of what the speaker is saying—triggers strict judicial scrutiny and will ordinarily be struck down.

Very different rules obtain, however, when state actors impose regulations in spaces—such as courtrooms or military bases—they own or control that have not been opened up to everyone to say whatever they choose. These places are “nonpublic forums” (or “limited public forums).” Here, state actors have much freer rein to regulate speech; they are allowed to impose content-based restrictions even on protected speech. A military base, for example, does not have to allow political marches. In nonpublic forums, restrictions on speech generally need only be “reasonable”—a very lenient First Amendment standard. But there’s one exception. Even in a nonpublic forum, viewpoint-based regulations—that is, restrictions based not only on the content of what speakers are saying but also on the viewpoint or opinion they’re expressing—are categorically barred. A military base couldn’t, for example, ban only pro-Democratic political marches.

All this is well-established doctrine, and in many ways the doctrine makes good sense. The core principle of the American freedom of speech is simple: no censorship on the basis of opinion. In the United States, no one can be penalized for expressing an opinion governmental actors deem too offensive or dangerous.

Few other countries honor this principle. You can go to jail for wearing a swastika or distributing Nazi literature not only in Germany but also in Canada and many other countries in Europe. In those nations, “hate speech” is a criminal offense. But the category of “hate speech” has almost no purchase in American law, because a lot of what’s called hate speech is in fact the expression of opinion, and U.S. law has always deemed it better to let people express their opinions, no matter how repugnant, than to let governmental actors dictate which opinions are permitted. Given the current climate, hate speech prosecutions will probably become more common in the United States soon. Connecticut recently arrested two men for uttering a racial slur, and New York City issued a statement in September 2019 declaring that using the term “illegal alien” with intent to “demean” or “offend” can violate the city’s human rights law (punishable by up to $250,000 in fines). But letting the government dictate what opinions are too offensive to be uttered is a fool’s game and is clearly unconstitutional under existing law. “If there is one fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” as Justice Robert Jackson famously wrote, “it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”

So the ban on viewpoint discrimination, by all state actors in all forums, is true to the fundamental principles of the American freedom of speech. At the same time, in nonpublic forums, content-based speech restrictions must often be upheld in order for the forum to function as intended. A courtroom, for example, couldn’t operate without myriad content-based restrictions on speech. In these basic respects, the First Amendment’s “forum doctrine” is sound.

Hence, if, for the reasons I described previously, Facebook and Google are state actors when they block objectionable content, a great deal depends on what kind of forums these platforms operate. Are they public or nonpublic?

It may be tempting to think of Facebook and YouTube as public forums. They’re both open to billions of people to engage in wide-ranging expressive activity. A recent appellate court decision found Donald Trump’s Twitter account to be a public forum. Surely Facebook and YouTube, it might be thought, are more like public forums than is a single Twitter account, even the president’s.

This view would have extraordinary implications. If Facebook and Google preside over public forums, almost all curating or moderating of content—including even arranging content by relevance or directing particular content to particular individuals based on interests—might be unconstitutional, because it is content based. Even plainly criminal content might have to be carried. In public forums, “prior restraints” are almost categorically prohibited. A prior restraint prevents material from being published in the first place, as opposed to allowing publication but subjecting the speaker to punishment after the fact if the speech turns out to be unlawful. Under present doctrine, if Facebook and Google are operating public forums, then all their blocking technologies directed at unlawful content begin to look like a gigantic prior restraint.

This means that Facebook and YouTube would seemingly have to allow, for example, child sex trafficking, offers to sell illegal narcotics, and even offers to sell nuclear weapons to be posted. (If this result is constitutionally required, the platform could not be prosecuted for carrying unlawful content.) To be sure, the individuals posting such criminal content could in theory be prosecuted, but given the realities of online anonymity (a problem that would worsen if Facebook were a public forum, because its restrictions on anonymous posting might themselves be unconstitutional), Facebook and YouTube could end up as new Silk Roads on a scale never seen before.

These mega-platforms need not, however, be viewed as public forums. Despite their billions of users, neither Facebook nor YouTube has ever thrown itself open indiscriminately to everyone to post whatever content they choose. On the contrary, both have always required users accept content-based terms of service before they can post. For this reason, both can and perhaps should be viewed as nonpublic (or limited public) forums.

If so, the rules of the road are very different. The categorical ban on prior restraints does not apply in nonpublic forums, so Facebook and Google could continue to block unlawful content. They would also be free to impose real-name policies and engage in content-based curating even of material consisting wholly of protected speech. But there is one line they couldn’t cross. They could not exclude material on the basis of viewpoint or opinion.

To give concrete examples, this would mean that Facebook and Google could continue blocking obscenity (which is not protected speech under the First Amendment) as well as pornography (which is), because these restrictions are content based but not viewpoint based. They could certainly block child sex-trafficking advertisements or offers to sell contraband. By contrast, political advertisements—which Facebook and Twitter have been struggling with in recent weeks—would pose a thornier problem.

Under existing law, paid political ads are clearly constitutionally protected. Even when such ads contain provably false factual statements, courts look at restrictions skeptically, in order to protect robust political debate; one of the most famous First Amendment cases of the 20th century, New York Times v. Sullivan, involved an advertisement of this kind.

What follows? A wholesale ban on all paid political advertisements, like the one that Twitter announced recently, would probably be constitutional as a content-based restriction—provided that no viewpoint discrimination is hidden in the definition of “political” or “advertisement.” But the opposite policy—allowing all political ads without screening for falsity—would be equally constitutional. It’s the intermediate policy, in which attempts are made to weed out “false news,” that would create the most problems. In a public forum, a policy of this kind would trigger strict scrutiny and very likely be prohibited. In a nonpublic forum, however, the result could well be different. In recent litigation, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld a ban on “false or misleading” advertisements on Seattle’s buses because those buses were nonpublic forums. Courts might well adopt similar reasoning for Facebook and YouTube.

One rule, however, would be clear. If Facebook and Google are state actors when censoring speech they deem objectionable, they could no longer block so-called hate speech.

Many observers on the right believe that Facebook and Google apply their hate speech policies unfairly, targeting conservative speakers arbitrarily or disproportionately. If so, that’s viewpoint discrimination in an obvious sense. But the problem is deeper. Hate speech regulations are invariably based on—and typically defined by reference to—the opinion or viewpoint the speaker is expressing, regardless of whether the regulations purport to treat all groups equally. Ordinarily, hate speech regulations prohibit speech communicating something derogatory (as opposed to commendatory) about certain people or groups; and distinguishing between utterances depending on whether they criticize or praise is precisely what “viewpoint-based” means. That’s why even proponents of hate speech laws have acknowledged that “rules against hate speech are not viewpoint-neutral.”

Consider Facebook’s “Community Standards.” Under Facebook’s hate speech policies, positive generalizations about minority groups are fine, but “negative” “generalizations” about a racial or religious or sexually defined group are forbidden. Declarations of the equality of all mankind or races or groups are permitted, but statements asserting or implying group “inferiority” are prohibited. However well-intentioned, these standards are clearly based on the opinion being expressed, which the Constitution doesn’t allow.

That doesn’t mean that every Facebook user’s account would be flooded with hate speech. Opt-in filtering can solve that problem. Facebook could continue to employ “Community Standards” filters, but instead of blocking material unilaterally, it could make those filters available to its users, who would decide for themselves whether to receive the content that Facebook deems objectionable.

I should emphasize that the constitutional rules I’m describing would apply only within the United States. Facebook and YouTube have the technological capacity to block material in one country that they permit in others. Thus other nations, not bound by the U.S. Constitution, would remain free to apply their hate speech laws to Google’s and Facebook’s operations within those countries. But just as the U.S. should not impose America’s understanding of the freedom of speech on the rest of the world, so too other nations’ hate speech laws should not dictate what can and can’t be uttered in the United States.

I’m not minimizing the problem of violent acts committed by those who see hateful content online. Some extremist internet speech undoubtedly leads to violence . But speech has been leading to violence for a very long time. The answer to dangerous speech can’t be censorship. The Bible and the Koran have led to killings and deaths on an order of magnitude far exceeding any internet-disseminated speech. That doesn’t mean those books can be suppressed.

For better or worse, as long as the First Amendment survives, hateful opinions will be as constitutionally protected in the United States as loving opinions. If someone in America wants to use Facebook to say that “White people are racist,” they have every right to, hateful though that opinion might be.

The astonishing power to censor public discourse now in the hands of a few private corporations exceeds any such power ever exercised in this country by any governmental actor. The threat it poses to democracy is not yet fully understood, but this much should be clear: The law should be doing something to counter that oligopolistic power over public discourse. But instead of countering it, Congress is using the mega-platforms’ censorship power to suppress speech that the government cannot constitutionally suppress itself. The courts should not stand idly by.