The International Law of Anticipatory Self-Defense and U.S. Options in North Korea

North Korea tested a Hwasong-14 intercontinental ballistic missile on July 4, rushing closer to posing a major nuclear threat to the United States. Just a few weeks later, on July 28, the Kim Jong Un regime tested another ICBM, this time with a range that may include major cities in the continental U.S.

North Korea tested a Hwasong-14 intercontinental ballistic missile on July 4, rushing closer to posing a major nuclear threat to the United States. Just a few weeks later, on July 28, the Kim Jong Un regime tested another ICBM, this time with a range that may include major cities in the continental U.S. To make matters more concerning, the Defense Intelligence Agency has said that North Korea might successfully arm an ICBM with a nuclear warhead as early as next year. And according to The Washington Post, U.S. analysts have concluded that Pyongyang has produced a miniaturized nuclear warhead that can fit inside its missiles.

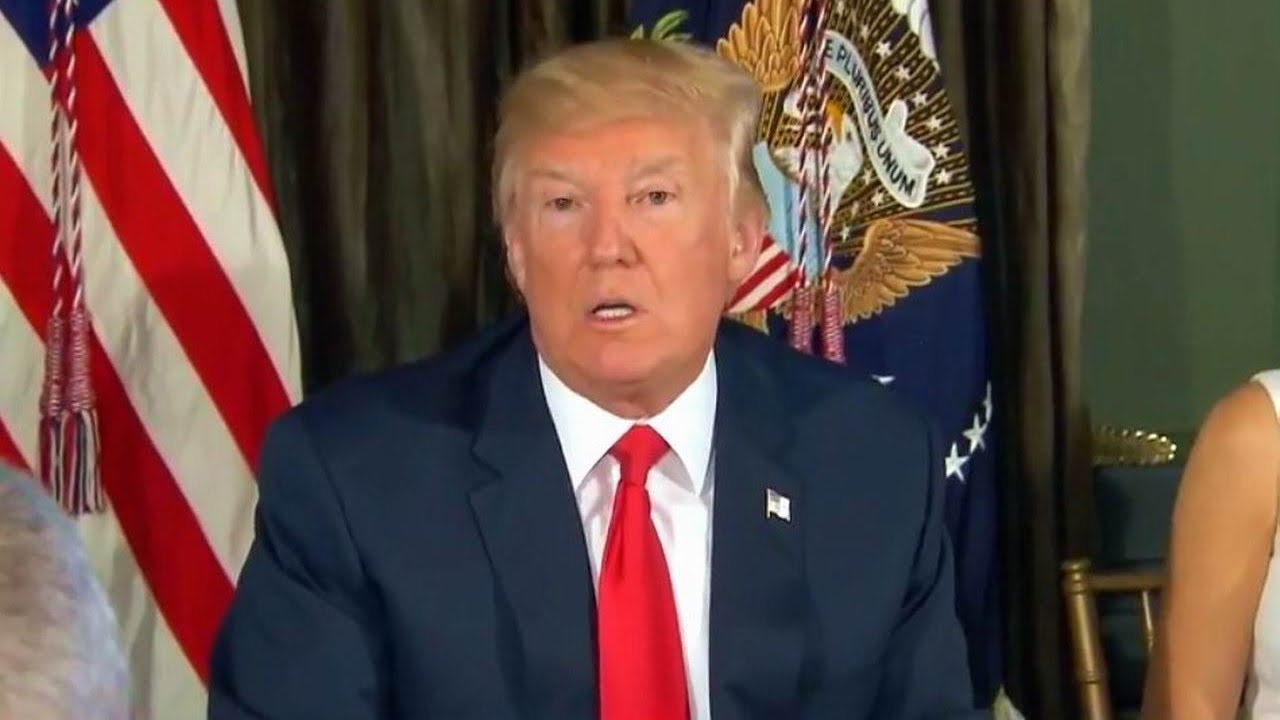

In a recent Atlantic article, Mark Bowden examines U.S. options for responding to the North Korean nuclear threat. While all paths forward present significant challenges, Bowden writes, he strongly advocates against an anticipatory attack on the North. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has repeatedly said that it is keeping all options, including a military strike, on the table—a path that could potentially result in the greatest loss of life in conflict since World War II.

Suspending consideration of the strategic questions that would factor into the decision, how would the U.S. justify a pre-attack strike on North Korea under international law? And how would the rest of the world react?

History offers a relatively small sample of cases to provide guidance on these questions; states simply don’t strike their peers in the name of self-defense all that often. When they do, experts and politicians often debate the asserted justifications for years.

This post reviews several examples of pre-attack strikes taken by a variety of states asserting self-defense; examining the context, rationale and international response. These cases might offer insights into an impending decision on the North Korean question.

What kinds of strikes qualify as self-defense?

In her book chapter "Taming the Doctrine of Preemption" (contained in the "Oxford Handbook on the Use of Force in International Law"), University of Virginia Law scholar and Lawfare contributor Ashley Deeks provides helpful definitions of the three terms primarily used by scholars to discuss types of pre-attack self-defense: anticipatory, preemptive and preventive. Her definitions are adapted below.

- Anticipatory self-defense often corresponds with the standard established in the famous 1837 Caroline case, in which British soldiers in Canada crossed the Niagara River to attack and send over Niagara Falls the American steamship Caroline that was assisting Canadian rebels. The British asserted that they attacked in self-defense, but then-Secretary of State Daniel Webster wrote in correspondence with the British government in 1842 that the use of force prior to suffering an attack qualifies as legitimate self-defense only when the need to act is “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”

- Preemptive self-defense tends to have a longer time horizon. In this case, a state often views an opponent’s particular, tangible actions as almost certainly developing into an armed attack against it. While there may be some time before the opponent can launch the attack, the opponent’s actions indicate an attack is likely should developments continue.

- Preventive self-defense seeks to halt the development of a future threat, often without having precise information about where or when the attack might occur. States sometimes invoke preventive self-defense even without specific evidence of the opponent’s capacity or intent to attack. Many states often consider actions falling within this category as illegitimate. However, some nations, including the U.S., have supported an understanding of self-defense that could include prevention under certain conditions.

Why does it matter?

How a state legally accounts for its actions, both in the public record and in the context of international organizations such as the United Nations, affects the legitimacy that fellow nations afford to the state generally and to its action in particular. A state that consistently acts in ways deemed illegitimate may experience damage to its global relationships or censure under international law.

What standards does the international community rely on when determining legitimacy?

When determining the legitimacy of a pre-strike action, both historical practice and statutory interpretation can influence the analysis. Clashes of interpretation can result in controversy over what types of pre-strike attacks states should consider lawful.

One major source of variation in nations’ legal analyses stems from differing views on the interplay between Article 2 and Article 51 of the U.N. Charter.

Article 2(4) forbids states from engaging in the threat or use of force against each other. Yet Article 51 says that the charter does not prohibit the “inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.”

As Georgetown professor Anthony Clark Arend explains, the restrictive school of interpretation believes that the language requires an attack to occur before one state can legitimately use force against another. But less restrictive arguments hold that a state need not wait until an armed attack has occurred to launch a legitimate pre-attack strike. This view leans on the weight of the “inherent right” of self-defense to argue that a state should be permitted to act to defend its citizens when it believes an attack is impending. Some taking the less restrictive approach also point to the French translation of the U.N. Charter, which uses the phrase “armed aggression,” as supporting a more flexible temporal approach to self-defense.

The U.N.’s 2004 High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change took a less restrictive view but qualified it, noting that:

according to long established international law, [a threatened State] can take military action as long as the threatened attack is imminent, no other means would deflect it and the action is proportionate. The problem arises where the threat in question is not imminent but still claimed to be real: for example the acquisition, with allegedly hostile intent, of nuclear weapons making capability.

Under the U.N. Charter, the Security Council has the sole ability to authorize the use of force against a state. If a state fails to receive this authorization but makes a pre-strike attack regardless, claims of self-defense will face much closer scrutiny.

When have states cited self-defense to justify a pre-attack strike?

Several brief descriptions of pre-attack strikes that relied on explicit or implied self-defense reasoning follow, each roughly falling into the subcategories described above. Arend provides a helpful overview of several of the below examples, as does Deeks. Their scholarship, along with public reports on the events, inform these descriptions.

- The Cuban Missile Crisis

In 1962, before either the Soviet Union or Cuba used force against it, the U.S. government instituted a “defensive quarantine” against Cuba. Some considered this to constitute a blockade under international law that is regarded as an act of aggression. Thus a blockade would violate restrictions on the use of force under Charter Article 2(4) or would require the U.S. to assert a legal argument claiming self-defense—a shaky proposition. By arguing that the defensive quarantine did not technically qualify as a blockade, the U.S. attempted to dodge the need to provide legal justification for the use of force.

Instead, in deliberations with the international community the U.S. focused its legal rationale on regional organizations’ power to authorize force rather than rely on legitimacy derived solely through self-defense. In Security Council debates over the issue, no clear consensus supporting or rejecting the doctrine of preemption emerged. Some indicated that while self-defense before an attack was legal, the U.S. had not met the strict Caroline standard.

- The Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, one of the most commonly cited examples of a preemptive strike, began on June 5, 1967, when Israel launched a surprise attack against Egyptian forces. In the course of the short conflict, Israel more than tripled its territorial claims while repelling an assault it believed posed an imminent threat.

Several factors went into Israel's decision to strike, particularly Egypt’s expressed hostile position, its decision to expel U.N. forces from the Sinai and its closure of the Straits of Tiran. Ultimately, after significant political negotiation and the failure or rejection of several other courses of action, the Israeli government decided on a military strike to defeat the perceived existential threat posed by Egypt, along with its allies such as Syria and Iraq.

The Israeli position has consistently presented the 1967 war as defensive, legally justified by the actions and positions of its opponents. Many historians take a similar view. Yet other experts and many Arab states have called the conflict a war of Israeli aggression and deemed it unjustified given conditions on the ground.

The Israeli action drew mixed international reaction, and Israel largely avoided criticism within the U.N.

- Operation Opera (Osirak Bombing)

On June 7, 1981, Israel launched an airstrike against the Osirak nuclear reactor in Iraq, close to Baghdad. Although the facility was not yet operational, the Israeli government feared Osirak would become capable of producing material necessary for a nuclear bomb.

In a statement after the attack, the Israeli government said that its intelligence indicated the reactor would have become operational by July or September of that year. Given that Israel could and would not attack a “live” reactor site for fear of nuclear contamination, it claimed to have a small window for action:

We were therefore forced to defend ourselves against the construction of an atomic bomb in Iraq, which itself would not have hesitated to use it against Israel and its population centers. Therefore, the Israeli Government decided to act without further delay to insure the safety of our people.

The rationale behind the decision explicitly employed the future tense: At some point Iraq would have nuclear weapons capability that it would then likely use against Israel, judging by its past statements and the beliefs of Israeli intelligence. Yet Israel lacked clear indication that Iraq had the capability to carry out the attack, shifting the action closer to prevention than preemption.

The U.N. Security Council, including the U.S., unanimously condemned the attack, calling it a violation of the U.N. Charter and international norms.

- Operation Infinite Reach (Al Shifa Bombing)

In 1998, the U.S. conducted its first “unreservedly acknowledged” preemptive strike against a terrorist organization. In a plan codenamed Operation Infinite Reach, the Clinton administration launched a missile attack on a factory in Khartoum, Sudan, that it said produced the VX nerve agent for Osama bin Laden. The factory, however, produced pharmaceuticals for the Sudanese population. Many Arab nations condemned the attack as a violation of Sudanese sovereignty.

As with other claims to self-defense, this classification has come under significant scrutiny. Some argue that the strike is better understood as a post-attack response to the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that had happened shortly earlier that year. Reports in the years after the Sudan attack showed that the intelligence used in the decision contained significant gaps.

- Invasion of Iraq

Although the George W. Bush administration legally justified its decision to send forces into Iraq in 2003 on the basis of Security Council resolutions, the administration relied in part on a claim of self-defense. The Bush administration argued that Saddam Hussein's regime armed with weapons of mass destruction presented a threat to both the region and the United States. In context of the Bush administration’s views and statements on pre-strike attacks in the National Security Strategy of 2002, this justification veered close to a doctrine of preventive self-defense: an allegedly guaranteed threat on a more ambiguous timeline that had to be stopped before it could achieve the capacity to strike. President Bush said in a speech Oct. 7, 2002:

Some ask how urgent this danger is to America and the world. The danger is already significant, and it only grows worse with time. If we know Saddam Hussein has dangerous weapons today—and we do—does it make any sense for the world to wait to confront him as he grows even stronger and develops even more dangerous weapons? … America must not ignore the threat gathering against us. Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof, the smoking gun that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud. …

The ideological framework underlying this policy proposal should not have come as a surprise. The National Security Strategy of 2002 explicitly suggested a more flexible understanding of what constitutes an “imminent” threat (which would legitimate certain military actions in self-defense). In it, the administration made similar arguments, noting that the government could use the likelihood of a future threat to justify immediate action.

- Operation Orchard (Al Kibar Bombing)

In 2007, Israel launched another airstrike, this time against a secret nuclear reactor named Al Kibar that had been constructed by the Syrian government in a remote part of that country. The attack continued the Begin Doctrine, an Israeli policy stemming from the 1981 Osirak strike, which said that Israel would not permit its adversaries in the Middle East to develop nuclear weapons.

The strike succeeded, covertly destroying the reactor. Intriguingly, parties kept virtually silent in the leadup to the strike and its aftermath. Details about the strike emerged only slowly. Deeks contrasts the lack of outcry over Israel's 2007 bombing with the swift international condemnation after the Osirak bombing, even though Al Kibar clearly did not meet the Caroline standards. She notes that WMD in the hands of states deemed unpredictable may affect international responses to strikes taken in asserted self-defense.

What can these events tell us?

The North Korean threat presents a host of challenging strategic questions regarding a pre-attack strike. This piece does not focus on the strategic logic or illogic of such a choice, which have been well addressed here, among other places. It considers instead a different question: What legal justification could the U.S. invoke should it choose to launch a pre-attack strike on North Korea?

First, we should consider which type of justification the decision would fall under. Assuming the U.S. has no immediate indication that North Korea is about to attack (eliminating the standard anticipatory self-defense requirement), the U.S. is likely to find itself somewhere between preemptive and preventive action. The North’s threatening statements and demonstrated technological development seem to indicate a real, rapidly approaching threat. Our knowledge of the weapons Pyongyang possesses and those the regime hopes to develop support the preemption classification. Still, preemption exposes the U.S. to possible legal objections and controversy.

The U.S. would probably argue that the North Koreans’ development of an ICBM and a soon-to-arrive nuclear warhead small enough to arm that missile present an existential threat to Americans' well-being and could destabilize global geopolitics. It could seek the authority of a Security Council resolution, in which case the legal question of an imminent threat would fall to the wayside—preventive force authorized by the U.N. Security Council is legal. But China and Russia have both shown willingness to support the North Korean regime in various ways, and their veto power over a Security Council resolution could prevent such a measure from ever coming to fruition.

In that case, the U.S. would likely assert that North Korea poses an imminent threat as per its understanding of Article 51 of the U.N. Charter and launch a preemptive strike. The examples above, and other instances not covered here, provide precedent.

But the approval of the international community for acts of preemptive self-defense—if it appears—stems from unique, contextual factors. The 2007 Al Kibar bombing faced little condemnation while the 1981 Osirak bombing sparked international outcry. Granted, the former benefited from more secrecy. But it was also a strike against an adversary that had progressed further along its path of obtaining destabilizing weapons and thus posed a more imminent threat. Perhaps in such a case international willingness to accept or ignore actions designed to resolve a major security threat increases. In the Osirak example, claims of self-defense appeared far more dubious as Iraq’s capabilities, and its intentions, were less clear. Although the threat included an alleged WMD component, it did not appear to pose imminent danger to international order, possibly leading to accusations of illegitimacy.

This key difference suggests a broader point: The threat of a rogue state with WMD casts a degree of unpredictability on how states, fearful but constrained, will react. While in some cases they may be more likely to support a pre-attack strike, in others they could worry about the target state’s response and the potential of an illegitimate and poorly timed pre-attack strike to spiral into broader regional or global chaos.

These strategic ramifications and the potential for long-term conflict appear especially concerning when decision makers may base their actions on non-public intelligence that, if one day revealed, could bolster or damage claims to legitimacy. This happened when intelligence—or the lack thereof—was released after the Al Shifa pharmaceutical plant bombing. More recently, the U.S. decision to enter Iraq in 2003, which was supported with questionable intelligence, continues to influence U.S. foreign policy (with, among other things, a Rand Corp. study noting that the experience in Iraq is likely to decrease U.S. willingness to launch preemptive strikes in the future). It is likely to continue to influence international perceptions of future U.S. claims of anticipatory legitimacy.

In short, the limited ground covered in this piece amounts to the following: The U.S. could make a substantial legal argument, based on international law and the precedent of some cases, for a pre-strike attack on North Korea. But the variability of historical examples and the behavior of Security Council members make it unclear what degree of legitimacy the international community would afford the United States’ fateful decision.

.jpg?sfvrsn=3f72484e_5)

.jpg?sfvrsn=104df884_5)