Lawfare Daily: The New U.N. Security Council Resolution on Trump’s Gaza Peace Plan, with Amb. Jeffrey Feltman and Joel Braunold

For today’s episode, Lawfare Senior Editor Scott R. Anderson sits down with Joel Braunold, Managing Director of the S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace and a Lawfare contributing editor, and Ambassador Jeffrey Feltman, the John C. Whitehead Visiting Fellow in International Diplomacy at the Brookings Institution, who previously served as Undersecretary General for Political Affairs at the United Nations as well as the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, among other senior U.S. diplomatic positions.

They discuss Resolution 2803, which the U.N. Security Council adopted earlier this week to endorse and help implement President Trump’s peace plan for Gaza, including how it conforms and departs from usual international practice, what it says about the political positions of the various parties involved in the peace plan, and how it may (or may not) help contribute to an enduring end to the broader conflict—as well as a possible path to Palestinian self-determination.

To receive ad-free podcasts, become a Lawfare Material Supporter at www.patreon.com/lawfare. You can also support Lawfare by making a one-time donation at https://givebutter.com/lawfare-institute.

Click the button below to view a transcript of this podcast. Please note that the transcript was auto-generated and may contain errors.

Transcript

[Intro]

Joel Braunold: Look,

my most likely scenario of what, of what will probably happen in the end is

we'll have ISF on the border, not in the towns. I just, I can't

imagine––whether that's on the yellow border, where is Israel currently is, and

then it slowly moves backwards, or whether that starts on the bigger border,

I'm not sure. I think that probably it depends on if they can get funders to

fund in the Israeli side of Gaza, if there isn't an agreement with Hamas.

Scott R. Anderson:

It's the Lawfare Podcast. I'm Senior Editor Scott R. Anderson,

joined by Joel Braunold, managing director of the S. Daniel Abraham Center for

Middle East Peace, and Ambassador Jeffrey Feltman, currently at the Brookings

Institution, but previously undersecretary general for Political Affairs at the

United Nations as well as an assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern

Affairs.

Jeffrey Feltman: And

it's very hard to imagine that even if there is a political process with some

kind of disarmament, DDR, decommission office, et cetera, that it will be

sufficient to meet the Israeli demands.

The Israelis are going to make the perfect the enemy of the

good. And we don't have good yet, but even if we do.

Scott R. Anderson:

Today we are talking about the new UN Security Council resolution embracing

President Trump's peace plan for Gaza and what it might mean for the broader

conflict.

[Main episode]

Scott R. Anderson: So

Ambassador, I wanted to start with you. We've had a dramatic and notable week

at the UN Security Council, even by UN Security Council standards, which is a

pretty high bar.

We've seen something that maybe some people thought would never

happen: a UN Security Council resolution strongly backed by the Trump

administration, hard fought for, and ultimately won, in some way anointing what

is really a pillar of the Trump administration's foreign policy as also a

pillar of the United Nations system’s foreign policy, at least in regards to

the Gaza conflict, of this particular moment in it.

Talk to us about the process that got to this extraordinary

resolution. This is UN Security Council Resolution 2803, for folks who haven't

been following, that buys into and endorses, more or less, the Trump Gaza Peace

Plan.

Talk to us about how exactly we got to this resolution, which

ended up getting votes from 13 members of the ecurity coCuncil and two

abstentions from Russia and China, letting it move forward.

Jeffrey Feltman:

Well, I mean, first of all, um, I mean, thanks for having me on. It's good to

be here with Joel.

It's a bizarre resolution. It's unlike any resolution that I've

ever seen. I worked for the UN as Undersecretary General for Political Affairs

for six years. I've studied UN––I've been part of the blob as we've been called

in Washington and New York, and I've never seen a resolution like this.

But I will say that the Trump administration, despite what some

of us may think about the Trump administration when they were coming into

office, despite what we may evaluate in terms of other statements, this is not

the first time that they've turned to the UN in this year.

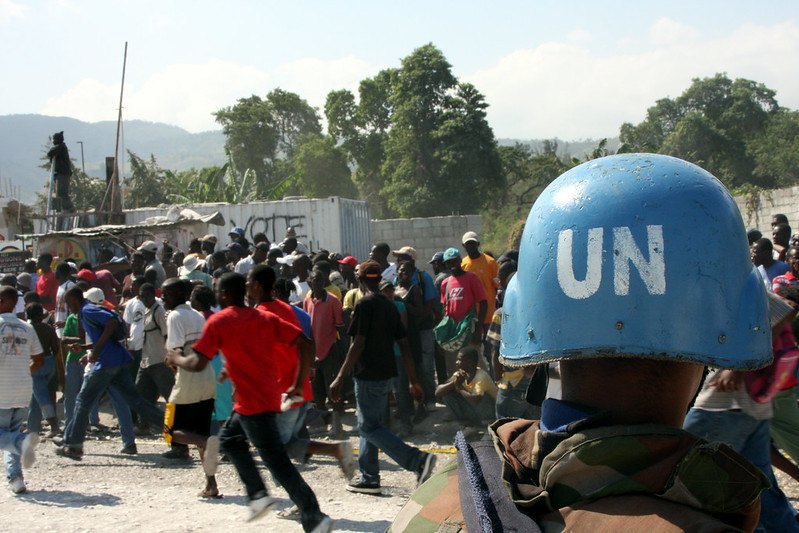

In September, they turned to the UN to create the Haiti gang

suppression force with another resolution. They went to the UN and pushed very

hard to get Ahmed al-Sharaa, the interim president of Syria, and his interior

minister off the sanctions list.

So in fact, there's a pattern now, that we can see where the

Trump administration has seen that there's value in going through the UN.

Now, the value may be because of burden-sharing in terms of

cost. Or the value may be that, that their realization that other member states

expect UN Security Council authorization. The member states that would

participate in the International Stabilization Force for Gaza that's in the

Trump Peace Plan would expect to have some kind of Security Council cover for

their participation.

So the resolution itself is bizarre in how it's worded in that

the Security Council is authorizing a Board of Peace without any clarity about

what the Board of Peace membership will be, the International Stabilization

Force without any idea the size of the ISF or the participation of countries in

the ISF.

So it's strange in that the Security Council seems to be

giving, you could say a blank check to the Trump administration to follow

through on the Trump administration's comprehensive plan, the Trump plan.

But it's not so strange when we see a pattern of the United

States going to the UN in order to get others on board.

Scott R. Anderson: So

it's an interesting note there, because it is kind of at least the most public

step in this process of turning to the UN.

How exactly did we get here for this resolution? We know early

on there were other drafts floated without discussions about Palestinian

rights, and we saw a careful massaging and negotiation around that language.

Can you give us a little bit of background about what the

negotiations looked like behind the scenes to eventually get to where we are

today?

Jeffrey Feltman: My

expectation is that when the Trump administration officials started talking

with people about the ISF, about the participation in reconstruction,

humanitarian assistance, people said ‘we gotta have the UN there, you know, we

need to have authorization.’

Now, there's some things that I expected to see in the

resolution ultimately that weren't there. You know, there's something called

Chapter Seven. Chapter Seven of the Security Coun––of the UN Charter is what's

usually cited for enforcement missions.

And the ISF, while it's not a UN mission, looks like it's

supposed to be an enforcement mission, which would usually require Chapter

Seven authorization authorizing lethal force, the use of lethal force.

That's not there. Although some of the language, Chapter

Seven-like language is there, “use all necessary measures.”

So I was kind of surprised that didn't get added. I would've

thought countries like the UAE would've said, ‘Hey, if you want us there, you

gotta tell us explicitly Chapter Seven.’

But I would imagine that what happened is, as you know,

officials and Trump administration looked at how to take that 20-point plan

from October and implement it.

They came to the realization that member states are going to

expect the UN. That 20-point plan itself is fairly vague. It has you know––each

of those 20 points can have a whole book written under each of those 20 points

to try to fill it out.

So you've got a vague resolution that refers back to a vague

20-point plan with the details still to be worked out.

And the Security Council said, go ahead.

Scott R. Anderson:

So, Joel, let me turn to you on some of that political context. How essential

do we get a sense that UN Security Council imprimatur was to some of the

parties that we expect to participate in this arrangement?

We know the UAE, a couple of the regional governments are

expected to play a major role, Mohammed bin Salman talked about as potential

member of the Board of Peace and the other organizing bodies.

But of course, we've heard other governments might be involved,

particularly in the ISF contingent. I think Indonesia and Pakistan have been

mentioned in the past few weeks. Other countries might be contributing forces

as well.

So talk to us about how, exactly, significant this was. Was

this a necessary precondition to getting this plan moving forward? Or is it

something that's become more of a––it has more symbolic value than actual

operational value?

Joel Braunold: Well,

I would say no UN Security Council resolution is just symbolic, right?

It has legal weight, even if it's weird. Much of the chagrin of

much of the international human rights and accountability community were

outraged by this resolution, given most of the things that Jeffrey just said.

That it's completely bizarre, doesn't reference previous resolutions and other

things.

Let's start this way. I think as Jeff said, the Trump

administration has gone to the UN when it finds utility. And in many ways, and

I think we've spoken about this before, Scott, everything with Trump world and

Trump foreign policy is about utility. What is useful, what is the tool that

gets us there?

I think that as we are now seeing on Russia-Ukraine, this idea

of not having massive peace accords, but having sort of an ideas document that

drives the situation forward is something that they like to do.

And that's what the 20 points was. And once it moved beyond a

hostage ceasefire deal, and then it needs boots on the ground, people need to

ask, well, what's the legal environment in which we're operating? Um, this has

always been a question, you know, according to the Oslo Accords, Gaza is a PA

zone, but of course it's not run by the PA 'cause Hamas took over in a coup.

And so what is the legal context of which you want to have the

World Bank fund things if the PA is not in control? And as one of the

conditions of the ceasefire, the Israelis were not countenancing that the PA

would be back at the table.

And so the UN Security Council resolution is essential if you

want to spend international mechanisms or send people's troops there with any

legal format that people feel secure.

Because as much as the Trump administration and the Israelis

really don't care about, you know, international legal things, it's just not

their, it's not their prime––while their legal systems, of course, work out and

do their different things, it's not their prime motivator. For many other

countries, of course, it's their prime motivator. They want to stay within the

bounds of international law. And this now gives not just the imprimatur, it

gives the mandate for them to now participate in this exercise.

Now we can get into the views from Jerusalem and Ramallah, and

they're very different. But what happened at the UN is fascinating because the

peace plan––and basically on the ground in Gaza, the PA, at this point, they're

not relevant. There's no one on of the PA in Gaza, and they're not a force to

be reckoned with. In Turtle Bay, the PLO has much more power than the state of

Israel, despite them not actually being a recognized state by the UN Security

Council.

So how the, what the dynamics were that led to this are

fascinating, and the spins that are going on in Jerusalem and Ramallah that are

happening in order for this to move forward.

But it is important to say in the text of the resolution, it's

basically the Trump plan. The language and the text around Palestinian

statehood, all the other things that are referencing, are all things that

occurred in the 20-point plan.

So despite these massive, shocking political screams that

sometimes you're hearing from Jerusalem, ‘how could it say a pathway to a

Palestinian state? How could it reference the French-Saudi initiative?’

I mean, that's what the Trump peace plan did. But there is very

big difference, in Jerusalem, from President Trump saying that and the United

Nations Security Council saying that. And that's an important distinguisher for

them as well.

Jeffrey Feltman:

Following up on Joel's good comments, it's worth noting that during the

negotiations for this text, after the initial draft was done and then there

were a couple revisions, Algeria was quite opposed.

Algeria is sort of a revolutionary country, you know, prides

itself on its revolutionary past. And it's also the site where Yasser Arafat in

1988 declared the Palestinian state. Algiers.

And so Algeria was representing the Arab group, was opposed to

this, despite all the other Arab countries that, that Trump mentioned being in

support of it. It was the PLO office in New York coming out and support this

resolution that got Algeria on board.

And as Joel and I were discussing just before you came on, it

also contributed, I think, to the Chinese and Russians deciding to abstain

rather than veto. Once the Arab group and particularly the PLO were on board,

it would've been very hard for China and Russia to––who were trying to enhance

their relationship, particularly with the Gulf countries––to then go against

it.

So the PLO office, as Joel said, was key to the passage of this

resolution in my view.

Joel Braunold: So

let's dig into why. Because it's fascinating that how, but why, right, why

would the Palestinians do this?

Because many of the international legal community, you know, if

they've just been declared a state by France and the UK, why then do you now

have a resolution that puts a pathway to statehood, subject to different

conditionality of something they've already recognized?

Something––that is where Jerusalem is finding solace. So let's

start with Ramallah, with your permission, Scott and Jeff, and then we can go

to Jerusalem.

So the Palestinians, especially in Ramallah, have been

struggling to get the Trump administration to articulate a West Bank policy. On

Gaza, we know that they wanted the ceasefire. But it seems and has been that

their entire perspective towards the West Bank has been in the context of Gaza.

Even when it comes to settler violence––which now Huckabee

today, Ambassador Huckabee said is terrorism. He says it's a minority faction.

That when Marco Rubio was asked about that Secretary of State Rubio, he said,

you know, this could upset the Gaza ceasefire.

So everything about what was going on in the West Bank was

subject to what it was doing in Gaza. So Ramallah was really trying to look just

like at the UN, how could we be relevant to the Trump administration?

And one thing that we've spoken about a lot on this podcast is

prisoner payments. You know, they had a hiccup on their implementation. You

know, it was big, reported two weeks ago, they fired the finance minister of

the PA. They've tried to get back on track to demonstrate they're an investible

property. And that, you know, Riyadh, who has been backing Ramallah pretty

heavily, you know, that there's something to talk about.

But the Trump administration needed Ramallah on this, okay?

They needed Ramallah in order to get the PLO office in New York to bless this,

for this to be able to move forward.

And I think that what Ramallah made the decision of was like,

look, we want to be relevant to the Trump administration. We can't spend

another three years on the outside being smacked around with this Israeli

government.

And for the first time, we've got the whole region dedicated

about putting the Palestinian issue back on the agenda. We can't be the ones

why this doesn't work if the rest of the region's on board.

So I think having the Saudis, the Qatari, the Turks, the

Egyptian, yeah, all of the endorsers of the deal pushing this puts Ramallah in

a difficult position they didn't wanna be in.

And they saw a political advantage. They said, look, if we are

endorsing this and Hamas is opposing it––which they are, okay, Hamas has come

out publicly and opposed it––we look like we are the positive actors and the

region will endorse us, and Hamas are the negative actors.

Now, publicly, it seems that the Witkoff-Hamas meeting that was

supposed to take place in Istanbul was canceled.

Why was it canceled? Rumored Israeli pressure, whatever. I'm

sure the others were like, if Hamas is opposing you publicly and Ramallah is

welcoming you publicly, why would you––Let the mediators deal with Hamas! Why

don't you deal more with Ramallah?

So Ramallah saw a chance to take a march on Hamas––and, a very

rare win for Ramallah, it's publicly popular on the ground, because

Palestinians don't want to see the war continue.

And as much as they don't trust Trump vis-a-vis their interest

versus the Israelis towards what, they see him as a very effective mediator.

And they saw that Trump managed to restrain Israeli action and stop the war. If

it requires them to accept this UN resolution, not only to keep the war being

stopped and not giving an Israeli excuse to sideline their political opponents,

and Hamas, and to build relevancy in DC while also getting wins from the region

by doing so, seems like a win-win-win.

Because otherwise they could have stood on their laurels and

saying, no, this is where, these are our rights and stuff. But the region and

the world would've passed them by.

And I think that they felt like, at this point, that there's no

utility in that. And there actually is a way to try and build branches to Trump

world.

But it is a big change for the PA. The PA's entire traditional

strategy has always been international law, moral authority, legal authority. And

even if that means power politics on the ground, it doesn't matter.

They made the strategic decision––which is controversial,

especially with the international diaspora––to sacrifice some of that by

supporting this in order to get real, on-the-ground victories for themselves.

Now the question will be, will their regional allies and their

own reforms enable them to build a West Bank policy with DC that enables them

to overcome some of the challenges they're having with Jerusalem?

Jeffrey Feltman:

Joel, fascinating and I agree with your analysis, which is much deeper than my

own would've been.

But Scott, it's worth pointing out that the PLO supported this,

that Ramallah supported this, despite the fact that there's even a little

poison pill in the resolution. Where it talks about, you know, the Board of

Peace will oversee basically everything.

The ill-defined board of people will oversee everything. But

there will be a group of technocratic Palestinians that might do the day-to-day

governance, service delivery, things like that.

And it says Palestinians from the Strip. Now, that was, I

think, intentionally put in there as a sought to Netanyahu in his cabinet to

say, ‘it's not Ramallah that's coming in, it's not, we're not, you know, we're

not giving this to the PA right now. We're not giving this to the PLO, because

it's Palestinians from the Strip.’

But it basically, if you follow the letter of the resolution, means

that people who have experience in Europe, in the Gulf, who are Palestinians,

who happen to be from Tulkarm like Salam Fayyad, would not be able to

participate in this because of the wording.

Joel Braunold: So

like counts as from the Strip? Ironically, there are PA ministers from Gaza,

right?

And so the question of the dotted line between the technical

board and the PA still needs to be worked out. But I think that for the Trump

administration, this was––they didn't want to negotiate the particulars at the UN,

right?

They knew that's not a strong place. But they know they needed

this in order to actually have a serious conversation with other countries

about how to move this forward.

So the PA got out of the way as a speed bump for them, a very

big gift that the PA gave the administration. I think that them and their

regional lives will now want to see, you know, that they're taken more

seriously because they were not, the fly in the ointment here, where they could

have been.

And I think that they made a strategic decision not to be, and

to actually get on board, which is interesting. And to steal a march, as I said,

domestically, build relationships with Washington, further their relationships

in the region. And to distance themselves, to––if the ceasefire fails now

because Hamas refuses to move along with this and the mediators can't get them

on board, the PA becomes the obvious address for where to turn to if Hamas

can't be reformed in a way that they will actually move this forward.

Scott R. Anderson: So

I want to come back to the Jerusalem view some of the regional reactions and

implications. Before we do that, I want to spend a little time on the technical

terms of the UNSCR itself and what exactly it means.

Because of course this is taking a U.S. proposal, which did not

expressly implicate the UN system at all, and bringing it into the UN system to

some degree. Although to what degree, I think is a question I want to put to

you, Ambassador.

What does this mean in terms of particularly the Board of Peace

and the ISF? To what extent are these integrated with the UN system or is this

really, as it says for the Board of Peace, a welcoming, a kind of casual

endorsement?

We don't see things that we've seen in prior things, like a

express grant of, like you said, Chapter Seven authorization for the use of

force.

We don't have any here even express grant of privileges and

immunities. It says you'll have authority to negotiate privileges and

immunities, but doesn't actually expressly give any for any involved personnel.

And it's not clear that UN rule, what the UN role is going to be, exactly, in

the Board of Peace, at least by my reading, or whether it's going to have a

substantive role versus more of kind of an observer participatory role.

So talk to us about our sense about how both those two key

elements––the Board of Peace and the International Stabilization Force it’s

supposed to establish––are likely to interact with the UN system moving forward

under this resolution?

Jeffrey Feltman:

Scott, it's worth noting that in the first draft of the resolution, there was

no reporting requirements at all to the Security Council.

The proposal was we authorized this up until December 31st,

2027, which is a long mandate by UN standards. Many mandates are only six

months, but most are every year. And with no reporting requirements to the

security council whatsoever.

So now there are reporting requirements written. The Board of

Peace is supposed to submit every six months a report to the Security Council.

But that's a very tenuous oversight mechanism for the Security Council. It's

not the Board of Peace and the International Stabilization Force do not rely on

UN-assessed contributions. So there's not a, there's not a budgetary oversight

that the UN would have.

There's some passing references to international law, including

international humanitarian law in the resolution, but there's no set

accountability or even specific reporting requirements. Most resolutions that

authorize a UN peacekeeping force, for example, would say, you must report on

blah, blah, blah.

There's none of that in this resolution. These are not UN

entities that were authorized by the Security Council. They're not relying on

UN funding. And all they have to do is give a report every six months.

There are references to the UN in terms of humanitarian

delivery, but it would be under the Board of Peace oversight.

So if you have UN entities that have been delivering

humanitarian assistance or trying to deliver humanitarian assistance throughout

the war, one wonders what their relationship is to the Board of Peace, because

you could read the board, you could read the resolution saying the Board of

Peace now has authority over these, how these humanitarian deliveries that the

UN has been doing will be managed, will be managed in the future.

So it's really a very tenuous relationship with the Security

Council in the United Nations. But I think that the members of the Security

Council ultimately decided that if you don't back this, then the UN––then the Security

Council becomes irrelevant.

It's sort of the same argument about Ramallah. This isn't, you

know, that probably a lot of legal offices in the Security Council capitals

looked at this resolution askance but decided that it's better to support it,

rather than put themselves in the category of being spoilers of possibly

risking the war breaking out again and of getting on the wrong side of Trump.

Joel Braunold: So I want

to pick that up, Scott, and sort of move it to sort of the Jerusalem view.

So I think that building up on what Jeff just said, that you

can see this in two very different veins, okay. And it depends about where you

start. Traditionally, if you look at, Trump won, right? The main point of a lot

of their foreign policy in the region, as evidenced through the Abraham Accords,

was integration of Israel into the region.

Okay. That was the whole aim and that was the driving force.

And you'd argue that continued to Biden, even when you listen to Secretary of

State Blinken or you listen to Jake Sullivan, the former national security

advisor, you know, all of their ceasefire arrangements were trying to restart

normalization with Saudi Arabia.

Okay. That was like part of the cadence of the whole aspiration

of what they were trying to do.

I think we've seen an inversion especially over the past three

months of the Trump administration, even if it's not a public strategy, but how

the region sees it. I think they see this Board of Peace, and the reason I

would say that they were willing to ignore their legal challenges and to move

forward, is they see this as a restraining of Israeli action in the region rather

than its integration.

We've seen Saudi and Turkey and Qatar all get massive

diplomatic and security wins from the US all in some way to sort of just being

like, we don't care about Israel's QME, it's qualified military edge. This is

irrelevant to us. These are allies who are helping us with problems and, you

know, they want to have weapons, that's fine and we'll sell them weapons.

They want to be a major non-NATO ally? You can be that. I think

that especially after the signing of the ceasefire agreement, the speed in

which the CMCC, the Civilian Military Coordination Center, was set up in Kiryat

Gat.

The fact that CENTCOM basically has been restraining Israeli

actions in Gaza, by the Israelis having to ask the Americans before they can do

something.

And yes, I'm aware that there were major bombings in Gaza on

the Hamas side today and what it is, but Netanyahu wanted to take more

percentages of Gaza after one of the, one of the ceasefire breaks, and the

Trump administration prevented it.

And now that we're seeing rumors that the US is going to build

a military base in Syria, and maybe that the model from Kiryat Gat can go there

and maybe even potentially in Lebanon, what you are seeing is a pushback of

what the Israelis have tried to do post October 7th.

Post-October 7th, the Israeli mentality was

international law, international boundaries, these are all irrelevant. The only

language this region understands is force, and we will enforce these things not

through UN Security Council mechanisms but through force of arms.

We've seen that in Lebanon with the ceasefire there, and the

argument was, we'll do the same in Gaza, and we'll do the same in Syria, and

we'll do the same with Iran, if that's what we need to do, and everywhere else.

I think that the region is seeing, and Ramallah, the best way to restrain

Israeli action is to put Trump there. The sort of argument that Trump made to

Ukraine that the best way to protect you against Russia is if I'm invested

there, I think that the Arabs see that very much vis-a-vis the Israelis.

If the Americans are there and that they're interested in

creating peace and they're invested there, then that's probably the best

restraint.

Now for the Palestinians, it's huge gamble. You are basically

believing that the President Trump will protect you against the Israelis. Now,

I'd say not only is there a utility argument that made them that and that the

region argument, but this Israeli government and their visions as they had

just, you know, as we spoke about Scott––four weeks before the ceasefire. We're

talking about annexing the West Bank, we're talking about expulsion of

Palestinians from Gaza.

And we've seen no annexation, no expulsion, no territorial

expansion in terms of the Trump declaring that to the Israelis, that they see

this as a restraining.

And now we get to the view from Jerusalem. When the UN Security

Council thing started, it was, you could hear the squeals coming out of

Jerusalem being like, we don't like the UN, we don't like anything with the

Security Council. We trusted it when it was President Trump, but not when it's

a UN Security Council.

And as this was being negotiated, it was clear that the Israeli

red line was, you know, no Ramallah. And as long as it's the text of the 20

points, that'll be fine.

But at the same time, on the ground in Israel, it's been very

clear in the opposition of said this, that their ability to operate in Gaza has

been restrained by the CMCC.

The CMCC has basically taken over all humanitarian aid work.

And we're seeing from reports that, you know, these aren't experts on Hamas or

Palestinians. This is, you know DOW, I should say now, DOD or Department of War

Pentagon, just can-do, what's the problem, let's solve it.

And sort of COGAT, who are the Israeli normally responsible for

the Palestinian Territories who are very restrained by their own politics or

sort of sitting on the side as CMCC’s moving forward.

I think Israelis understood that, but we've seen over the past

week different very pro-Benjamin Netanyahu media outlets in Israel, Amit Segal,

Channel 14, sort of spin this as this isn't so bad. You know, this is really,

you know, these states who recognize the state of Palestine, now, clearly

they've had to vote on this and they haven't recognized the state of Palestine.

You know, the PA has to go through these reforms. It's going to

take them a millennia to go through these reforms and, you know, it's never going

to happen. So Jerusalem's trying to find a way that it can dictate, saying this

is fine. It's just basically not real, and don't worry about it and don't lose

any sleep about it.

But when you actually take a step back for the first time,

you've got internationals involved in Israeli business in a very significant

way. International troops are going to be involved in some way. Now, as we

said, we don't know, you know, they, the Israelis want them to disarm Hamas.

How is that going to work? What's that going to look like? Are they going to be

in between the IDF and Hamas? What does that look like?

These are things that the Israelis have tried to prevent since

the establishment of the state of Israel. They did not want international

forces on the ground. They now have international forces on the ground.

And I think that from some regional perspectives, the hope is

that what started in Gaza can flow to the West Bank and eventually it can go

there. Now the Israelis will resist that with tooth and nail. The Israelis will

claim that this UN Security Council resolution, for the first time since Oslo,

really splits Gaza and the West Bank into two territorial categories and

doesn't allow them to come back.

And so how this is implemented will dictate whether this is the

Israeli vision or this is sort of the regional international vision.

Scott R. Anderson: So

that's really useful context to bear in mind. It's these two perspectives that

brings us to one of the primary questions we're going to face. Kind of the next

phase of this, which is the composition of this Board of Peace.

We only really know one individual who's on it. That is

President Trump. We know Tony Blair was involved in organizing it. He's ref-,

discussed as, you know, a possible deputy effectively, or some other sort of

day-to-day head. Because presumably the president of the United States cannot

actually be that involved day-to-day in what this will be doing.

Other people involved, you know, Mohammed bin Salman, crown

prince of Saudi Arabia, other prominent regional figures, presumably Turkey,

Qatar. The other guarantees of the peace in Egypt will have representatives as

well.

I'm kind of curious if you have a sense, Joel, first about who

we are expecting to see beyond that kind of list of most likely folks. And for

you, Ambassador, actually maybe I'll start with this.

One thing that UN Security Council resolution does, I think is

interesting is that it actually defines a limited scope of what the Board is

supposed to be doing, or at least that what it is authorizing the board to do.

It's actually one of the few active, affirmative, what in kind of lawyerspeak

we would usually think of operational provisions is that it actually authorizes

member states to participate in the BOP and kind of subordinate bodies it has

to establish for certain enumerated purposes that mainly line up with the

agreement, but nonetheless are constraining to some extent.

Is that an avenue that of influence for the UN Security

Council? That scope of authorization, that it gives it a little bit of a foot

in the door for saying, ‘Hey, BOP, if you go too far beyond your scope, if you

go too far to what you're doing, you, if you run too far beyond what we defined

here, that's space for UN security, UN pushback or criticism.’

Or is this really, it struck me as one of the weirder

provisions and in is otherwise a fairly soft document, to be very specific in

enumerating specific areas of responsibility. I'm just kind of curious what you

think of the operational or political effect of that.

Jeffrey Feltman:

That's kind, I'm trying to play it out in my mind and I'm not, I––you know,

unlike you guys, I'm not a lawyer, so I'm looking at this from the politics of

the Security Council.

Let's say that the Board of Peace does something that, that

goes well beyond the language there. Would the Security Council remove its

authorization? Before the expiration? I can't see that happening. The U.S.

would veto resolution that would remove the, that would remove the

authorization.

As I said, there's no financial stakes for the UN. I suppose

that the UN could, to the extent that the UN is participating with the border

piece on delivering humanitarian assistance, I suppose they could say, as they

did to the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, you know, we're not, we don't want to

work with these people anymore.

That, that could be one aspect. But in general, I don't see the

UN Security Council having the tools to enforce strict application of the

authorization to the Board of Peace.

And you probably saw António Guterres’s warm welcome of the

Resolution. I mean, first of all, there's a relief, there is a resolution on

Gaza that passed. But I think part of it is António Guterres, like the Security

Council, like the PLO in Ramallah, wanted to make sure that he, that the UN

system––not the Security Council, but the system, the Secretary General and the

secretary, all the agencies, funds and programs––were not going to be an

obstacle, were not going to be on the wrong side of this.

Scott R. Anderson:

And so I think that puts really kind of the imprimatur on who exactly is going

to be composing this Bureau of Peace to determine what exactly they're going to

be doing. If there's not that much constraint that can be imposed beyond, you

know, at least before that 2027 expiration of this authorization.

Joel, talk to us a little bit about that. And Ambassador, I

invite you to weigh in as well.

Who do we think is going to compose this body? And you know,

frankly, at what level––you're going to have a body of these technocratic

Palestinians operating beneath it, but frankly, in most bodies, you would have

something between the president and the technocrats executing the day-to-day

policy, keeping things on track. Who is likely to be the functional day-to-day

people with responsibility for manning this enterprise?

Joel Braunold: So two

things. One I am also not a lawyer. Just full disclosure. So-

Jeffrey Feltman: You

sound like one. You sound like a very good one.

Scott R. Anderson: I know

that's not always a compliment, Ambassador. You should be careful.

Joel Braunold: My

mother would be very proud of you saying such things, but no, I'm a philosopher

by training. I'll take that one as it goes.

Okay, so all we have, Scott, are two things. We have President

Trump's statements where he said, I think it was yesterday, lots of world

leaders want to be on this Board of Peace and everything else.

I think we're looking at world leaders. You know, you said

Turkey would be on this board. I think the Israelis would have a heart attack

if President Erdogan was on the Board of Peace.

And yet this is the point. Do they have any control now on

who's on the Board of Peace? Did the Israelis exert any control? I don't know

how they could, they basically, they––both sides have basically said to the

White House, you deal with it. And both sides are hoping that the White House

is on their side.

If you look at the past three weeks, if you're in Jerusalem, is

that really a smart bet? If you are in Ramallah, what else have you got to

lose? So who's on the Board of Peace? It is completely in the hands of

President Donald J. Trump.

And I'll say something else that I said to Jeff beforehand, and

something that I've looked at in my non-legal sense. When I looked at the

resolution, when I looked at the Board of Peace in this peace deal, it did not

say President Donald J.

Trump would be the chair. It said that Donald J. Trump would be

the chair. So is this a post post-presidency as well? I note that the mandate

runs out technically when his term of office runs out. Are they just hoping

that a Democrat does something different?

What happens if JD Vance wins and decide, you know, my former

boss, this is a great way to keep him involved? Is this in, you know, ad

infinitum, in perpetuity? I don't know.

And I think there's massive questions there. Is he financially going

to benefit? Are we going to see Trump properties all over Gaza, like seriously

and legitimately? The other document we have is the Times of Israel leaked the

Blair plan that the President Trump's team were looking at.

And they had an entire org chart about where the Board of Peace

would be. There'd be an executive secretary that would have various different

elements, and then there'd be a technical committee that would sit under them.

So there are org charts that sit under that. I think that what Jared Kushner––and

when Steve Witkoff isn't solving every crisis in the world have been doing over

the past few weeks is running around the region trying to understand who will

get involved, who will fund on what.

I think where we're up to right now, and this goes to the Board

of Peace, is a bit of a deadlock. The UN Council Resolution was essential if

you wanted anyone but Qatari money to be funding anywhere in Gaza. So you've

now created a mechanism that it doesn't just need to be Qatari money, which is

good from the Israelis’ perspective and from the region, who doesn't want to

see Qatar just dominate this space.

The second piece is, will Hamas agree to disarm? And at the

moment they've said no, so the mediators are now going to have to push about

what does disarmament look like now in the Board of Peace Resolution in the ISF

and in the ceasefire, the Israelis got in there.

There needs to be milestones and timetables and everything else.

And the Israeli expectation is that the ISF will do this disarmament. And if

they don't, then the ceasefire’s off and the Israelis go back to war.

I mean, can Hamas get away with some level of symbolic

disarmament? Do they take their offensive weapons out and that's enough for the

Americans? Like who gets to say it's enough?

And it seems it's going to be this Board of Peace. Now again,

if the board of peace is stacked full of guarantors of the agreement and

regional actors who want to see Gaza, just, they want to see this stopped and

do not have the same interest as the state of Israel in terms of their risk

assessment, the level of disarmament necessary, I would argue, would be less

than if this was just the Israelis making the call. The only two countries that

are called out that need to be consulted with Israel and Egypt because they

border these and that whatever happens on the ISF needs to be coordinated with

them.

At the moment, we've got Gaza split into two. I can't imagine,

unless there's one single governance construct, that you are going to see

anyone outside of the Qataris willing to fund in just the American Israeli side

of Gaza if that's being run by the IDF. I just don't, I can't imagine that's going

to happen.

And I don't see us, as taxpayers in the U.S., I don't see

Congress giving the administration the resources to do that. One of the only

places that Congress can actually play a role, because it's something that the

administration want to spend on.

So Hamas now becomes the major question. And I think that as

Kushner ran around the region, there was a question of, what is this going to

look like? Who's going to fund and how are you going to get involved? I think

that Hamas at the same time, has been reconstituting its power on its side of

Gaza. And we've had this whole issue of the 200 Hamas members in the tunnel.

And I'll finish this quote, this answer, off with this, 'cause it's very

indicative of what's going to happen.

You have 200 Hamas, it seems, militants in a tunnel. And they were

on the Israeli side. And so there was a whole negotiation about how could you

get them out or do they have to surrender? Do they have to surrender to the

Israelis? Do they have to give up their weapons? Could they be given third

party transfer? The Turks clearly got involved and got Hadar Goldin's body back

as part of at least the beginning of the opening of the negotiation, which was

a very big deal in Israel.

So now the Americ––like a lot of the guarantors, like, they

gave back the body, the guarantee was that if they give up their arms, they can

go and they have amnesty.

The Israelis are like, no. And that this is now the test case

for the ceasefire. You have 200 people on the Israeli side. What is necessary

if they agree to exile? Which country is going to take the?

And at the moment, there haven't been any takers to who's going

to take them. So these now very practical details that everyone kicked to the

long grass, we'll deal with it as everyone deals with the Board of Peace, now

it comes down to what happens in Khan Younis. Now it comes down to what's

happening in Deir al-Balah.

It's not about palaces in Dubai and in Riyadh and everywhere

else. It's now about the real difficulty of people who have survived an

atrocity, right? And now as they're trying to rebuild their lives, how's that going

to work?

And the last thing I'll say on this, outside of disarmament,

all of this mythology that people are going to move to these megacities and Rafah

when they're originally from Gaza City, I mean, that's not how Gazans work.

Gazans are from particular areas and have particular property

rights, especially those who chose not to leave and decided to stay on their

land. They're not just going to give up their land rights to move somewhere

else. And so now, as the rubber hits the road and how this going to work, it's going

to become extremely complicated.

And again, the Board of Peace is now legally responsible for

that piece of territory. That is not the state of Israel, that is not the state

of Palestine, and that is not Egypt. It's this new entity. And who staffs it,

if it is regional actors, will diminish and dilute the Israeli ability to

affect it and will only have the American chairmanship as the hope that will

hold their equities in that.

Scott R. Anderson: It,

it's a fascinating structure.

And I would note just one oddness that's jumps out here, is

it's actually almost a three-tiered structure of leadership. Because you have

both the Bureau Board of Peace. But in terms of defining the benchmarks for IDF

withdrawal and other key aspects of implement agreement, the BOP actually

doesn't clearly itself actually have a role in that.

That’s actually agreed to by the ISF, the IDF, Israelis, the

United States, and then the guarantors. Which is never actually clearly defined

anywhere, but presumably the four states that are involved in enumerating the

agreement

Joel Braunold: You

tell me how the Turks and the Israelis are going to come to an agreement on

what those milestones look like.

Like I just, it's just an absurdity. But practically the

Americans are going to run the ISF, even if it's not their troops on the

ground. That'll be them in Kevlar.

Jeffrey Feltman:

Because the same ambiguity is on the Palestinian reform package. You know, the

Palestinians is supposed to comprehensively reform, but it's not clear in the

resolution who decides exactly, okay.

The PA's reformed enough that now, and the reconstruction

started that now the PA can go back to Gaza.

Joel Braunold: And

are we taking a reformed new Palestinian society in Gaza and implementing that

in the West Bank? Are we taking West Bank standings and putting that into Gaza?

When you are Israeli, the three things you care about most are

prisoner payments, education, and incitement. Sort of media incitement, right?

But do they really care about health standards? Do they truly

care about building codes that Ramallah has been pushing in their area? No.

So are there places that you could import––and we've already

seen this on Rafah, the agreement said that we are going to use the same

agreement that was in January. The January agreement about Rafah was EU ban

with basically non-identified PA officials on the border stamping passports,

saying that this is still a sovereign ancient entrance into Palestinian

territory. So they're finding ways that they can live with the compromises

politically on both sides.

This entire thing is a fudge. It's a fudge to try and move this

thing forward and allow each side to claim its same victory speeches. I

actually think that's very smart diplomacy, given the intractable nature of

this.

But which way this actually goes depends on who convinced

President Trump they're more useful, which goes back to the beginning of the

conversation of Ramallah. They've, in my view, correctly diagnosed with the

help of regional actors helping them understand this that the critical thing to

understand is if you are useful, you have a seat at the table.

I think the UN's got this. The Israelis are in the difficult

position that they are constantly the squeaky wheel of saying no, we can't deal

with this, no, we can't deal with this, no, we can't deal with this. At what

point does that Israeli ‘no’ become so frustrating to the White House that they

just steamroll over it? We don't know, and maybe it won't.

Ambassador Derm––with Ron Dermer now stepping back in a formal

role, there's a real hole in that U.S.-Israel relationship and Israel's also

going to elections where the populist mentality is not one that is

conciliatory. So how did the Israelis deal with their own internal politics as

this is being set up over the next 12 months while they're going to elections

is incredibly complicated for their own politics.

Scott R. Anderson: So

I want to get to this question of Palestinian reforms and next steps. Before we

do, though, I want to spend just a minute on the ISF itself, Ambassador. We've

already talked about the fact the ISF is not going to be a UN peacekeeping

body. It's not going to get UN peacekeeping funds. Presumably this is going to

be completely independent entity run up by different member states with

contribution, maybe kind of like the MFO in the Sinai, which has been kind of

operating on multilateral, bilateral non-UN grounds for half a century.

Now at this point, give

or take, do we have a sense both who is going to contribute to this and what it

means that there isn't Chapter Seven authorization for what it's doing yet?

It also that this resolution also clearly endorses certain

tasks that it will be responsible for. That will entail presumably, at least

the threat of the use of force, most likely the actual use of force. So from

this document, do we have a different sense about what exactly its scope, it's going

to be who's likely to participate, how its structure might look, or is that

still just a black box that we're all guessing at?

Jeffrey Feltman: I'll

be interested to, to hear what Joel has to say, because I think it's still

pretty much a black box. I think it's a conversation that's going on between,

you know, Washington's envoys Jared Kushner with comp, et cetera, and a lot of

different countries.

It's worth noting, Scott, as you well know, that the Security

Council has authorized other non-UN forces at times. This is not unique in

being a non-UN force that has UN Security Council resolution. You can go back

to Bosnia and the IFOR after the date in Accords, for example, or the, now the

gang suppression force in Haiti. So that's not altogether unique, but I think

that what's unique is that it's so ill-defined when it came to the Security Council

for authorization that it's not clear.

There's not even a, there's usually, in a Security Council

resolution, a discussion about authorized troop levels, even if it's not a UN

peacekeeping force. There's no mention of that in this resolution. And you hear

numbers like 20 to 30,000 being needed an area that's only twice the size of

the District of Columbia, that's now divided into two.

So you would have, you would have IDF on part of it, 20 to

30,000 on the other part. Hamas, who knows? But I would guess that there are a

lot of governments that are saying, you know, we don't want to disappoint

President Trump. We need to find a way to do this, but how are we going to do

it? We don't have the Chapter Seven reference.

Hamas has opposed this. We don't know, as Joel had mentioned

earlier, whether there's going to be renewed IDF conflict. We get stuck between

the IDF and Hamas. I mean, if Israel couldn't demilitarize Hamas with all of

the methods that Israel has used over the past two years, how would the ISF be

able to demilitarize Hamas, decommission all the weapons without some kind of

agreement with Hamas?

You know that I think that you're going to, that the countries

that would be most interested or the most likely countries would be countries

that would believe that they have the type of relationship with Hamas, that

they would be able to come up with a method short of using lethal force to have

some kind of disarmament. And that'd be countries like Turkey and Qatar, which

are going to be anathema to Israel.

Joel Braunold: The

Israelis have already banned the Turks from submitting troops, you know, they

said no. So the Turks’ position's ‘fine, we can't guarantee the agreement.’ You

don't want to, and I think that they've said that to the Americans. And the

Americans are like, that's pretty logical.

And then said to the Israelis, what do you want to do now? I

mean, the Indonesians have publicly pledged 20,000 troops. They said that in

their UNGA speech.

I don't think Indonesians speak Arabic, or if they do, I don't

think it's colloquial or Palestinian Arabic. And you know, the President Trump

keeps talking about the Grand Field Marshal of Pakistan.

So I'm assuming that the Pakistanis have made some level of

commitment, but I don't know what that looks like.

Jeffrey Feltman:

Although Pakistan also said that they thought it should be blue helmets that

they expected to be, you know. Yeah.

Joel Braunold: So I don’t

know what that looks like. Look, my most likely scenario of what will probably

happen in the end right, is you'll have ISF on the border, not in the towns.

I just, I can't imagine––whether that's on the yellow border,

where is Israel currently is, and then it slowly moves backwards, or whether

that starts on the bigger border, I'm not sure. I think that probably it

depends on if they can get funders to fund in the Israeli side of Gaza, if

there isn't an agreement with Hamas.

But I think you are going to have Palestinian-trained security

forces that have significant security backing by the Egyptians and potentially

by the Israelis by not getting in the way of doing a lot of this. And Hamas

having some very symbolic disarmament in terms of the, like very clearly

offensive weapons being put into warehouses in places under lock and key and

under monitoring in some way.

But it, for all of that to happen, Jeffrey, the argument is

that Hamas agreed to this was the 20-point plan they agreed to. Now, President

Trump agreeing, saying that Hamas agreed, even though they had only agreed to

the first seven points of his 20 point plan and not the other 20, is part of

the problem.

And Hamas's rejection of this right now, the mediators are going

to have to get onto them and just be like, you've got to find a way to live

with this and find a way. But to have disarmament absent of a political process

again, seems to be an anathema.

Which is why, added to the UN Security Council resolution, were

the last three points or the last two points of President Trump's plan that

spoke about a pathway to a Palestinian state and also a political process

sponsored by the United States.

Because to have disarmament without that, it's just not going

to happen. Or also like it's not going to be a yes/no question. There's going

to be phased. And is there a role for a reformed different political party that

isn't Hamas to stand in the PLO elections, and then you could have one––and

then is there like a DDR system just like there was after the Second Intifada,

while the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades became part of PASF?

Does Hamas militants, some of them get brooms and some of them

get guns, like we've seen in other conflicts? So there are opportunities, but

all of those require significant involvement. And I don't know if we're there

as parties yet.

Jeffrey Feltman: And

it's very hard to imagine that even if there is a political process with some

kind of disarmament, DDR, decommissioning weapons, et cetera, that it will be

sufficient to meet the Israeli demands.

That the Israelis are going to make the perfect the enemy of

the good. And we're, we don't have good yet. But even if we do.

Joel Braunold: So

that, that's the question, again, to the Board of Peace. And let's look at the

events of today. Israel claims Hamas broke the ceasefire. Clearly they had

America’s permission to go, and they killed 30 people.

And they were going after Hamas commander, which breaks their

commitment not to hunt down Hamas. Because they're like, if you break your

commitment, we'll break our commitment. And from the Israelis, they're like,

look, they said they'll disarm. Where's the disarmament, right?

But then they'll also say back that you––as in we, the Israelis––promised

that there would be, if there are PA reforms––against your PA reform point,

Scott, you've got, again, the two-headed Israeli government coming out, where

you've got Belazel Smotrich, the finance minister, every day.

He took 25% of Sebastia, which is Area B, yesterday through the

civil administration, and just sort of eating away at the West Bank. You've got

massive levels of violence being perpetrated by Jewish terrorists against

Palestinians in the West Bank. Now you've got Palestinians now committing

terrorists attacks against Israelis in the West Bank. That's heating up.

Because you can only keep the stuff quiet for so long.

Ramadan's coming in February. I'm very worried about that. Again, we, it's been

kept quiet for the past two years, but if this is boiling, what does that look

like?

You can't end this without there being some sort of pathway

forward. And so the peace plan transitioned the Israeli pressure on the PA from

collapse to reform. But not the entire Israeli government is there. And most

importantly, I'd argue, the Likud, which makes up the central part of the

Israeli coalition, they're in their primary system right now, and their primary

voters are far closer to Smotrich and Ben-Gvir than they are to Prime Minister

Netanyahu, and especially when it comes to the PA.

And Bibi's now being attacked from the opposition to the right,

saying, you've now agreed to a Palestinian state. You are agreeing to

resuscitate Ramallah. They haven't reformed.

And so it goes back to, the PA has to demonstrate that it can

reform. And that's not just their commitment to the Europeans or to the

Americans; it's to the Gulf and to the Saudis. They have to demonstrate they

can reform.

It starts with prisoner payment reform. They have to complete

it and be able to pass an order that they've gone through and that this system

is done. If they've done that, they then need to move to education, and

demonstrate that there are reforms there and then that they've made a

commitment to the Europeans of elections within a year.

If they can do those, they've resuscitated themselves to the

point that they will become increasingly more relevant. And politically, for a

president in the White House who cares about utility, they were not a sticking

point, but they were helpful. And so can they parlay that into having a policy

that includes them and moves their political issues forward as well as going to

be the open question of the day.

Scott R. Anderson: So

we've only got a few minutes left together. Let me move, ask you a bit of a

concluding question or maybe a ask you to look forward a little bit, Ambassador,

drawing from your long experience with reasonable precedent for this––what is, in

the end, an unprecedented sort of resolution and peace plan, but you've seen

the United States engage with the United Nations system in a lot of different

areas, both Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We of course saw a similar UN imprimatur

following the U.S. invasion of Iraq that helped establish the transition

process there, transition forces. In some ways, positive model, in some ways a

negative model, and cause problems that are hopefully people are learning from.

Where do you think this fits into that trajectory? You know,

what are the lessons that you think people will look back and take away from

the good things about those things it might accomplish, how effective it might

be? What are some of the things that give you concern that people may look back

on and regret, either from the perspective of the United States, the parties to

the conflict, or the broader UN system?

Jeffrey Feltman: I

mean, I would be very surprised if anyone that was involved in drafting this Resolution

2803, looked back at the Peace Implementation Council of Bosnia or the Iraq

example, or Timor-Leste, or Cambodia, you know, that even though there's been

other examples of UN Security Council authorizing, sort of, governing

institutions, transitional governing institutions, be they UN or be they non-UN,

I doubt that this resolution was rooted in any of that experience.

I would be very surprised if anyone looked at any of that

anyway. But what concerns me is. I don't think we have much time for this to

work. The example that Joel gave of what happened today is shows the risk––we

look at what's happening in Lebanon, where the Israelis are the impatient with

the disarmament of Hezbollah and they’re increasing their strikes in Lebanon.

I think that if the Board of Peace and the International Stabilization

Force, whatever we may think of the legal mandate behind them, if they don't

get started on that, what Joel described as restraint, we're going to be back

to war.

I hope that there is more going on in terms of implementation,

in terms of building the structures to make this work than is apparent to me

from the outside.

Scott R. Anderson:

Joel, let me turn to you and put it one more, a little bit different, political

context, and regional context. And that is the broader arc of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict that you know better than just about anyone.

This is a notable document, right? Do you like the peace plan

itself? We have seen, at least the way I posit it, in a piece that I've gotten

a lot of criticism for, for Brookings a couple weeks ago, it kind of brought

the two-state solution back from the dead from a U.S. policy perspective. All

of a sudden in a version of the two-state solution is a bipartisan point of U.S.,

foreign policy of some sort or something like the two-state solution, how

meaningful is that likely to prove?

The Palestinians are making a big bet here saying by getting

what is a, you know, weaker, but nonetheless, you know, bipartisan,

ideologically, departure endorsement from the Trump administration by saying,

having the Trump administration say, yeah, we see and are working towards a

path towards greater Palestinian autonomy and self-determination in statehood

former, otherwise, they see that as a big win.

I'm curious how you feel about that? And how much of that

hinges on the success of this plan, the success of the broader peace in Gaza, what

happens in West Bank? What are the component parts to see that strategy that

the Palestinians need to be leaning into bear fruit that we should be watching

in the weeks to come?

Joel Braunold: Scott,

you know, it's really an answer for a full podcast that I know we sometimes

podcast on. We may do that again sometime soon. We do that again sometime soon.

Look I think that if you are the Palestinians, the first Trump administration

was a heart attack administration for you.

You started off with big hopes. Basically you got deflated. The,

lots of your red lines were breached. A peace plan was put down that destroyed

all of your red lines. You became a party of ‘no.’ The region abandoned you.

The Saudis broke off relationships with you and the region normalized relations

with the state of Israel.

You then went through the Biden administration, where they

couldn't even get the consulate reopened to you in Jerusalem. And despite many

promises and pledges, nothing really happened. You had sort of an [inaudible] process

that on paper was supposed to build some relations between you and the

Israelis, but never was implemented. And I think President Abbas, during that

time, made the decision that there's really no point in dealing with the state

of Israel.

Or at least under this government, there's no, there's nothing

to talk about. And sort of went and said, I'll rebuild my relationships with

the Abraham Accord countries, which he successfully did with Morocco and the

UAE and especially with the Saudis. And what I want in return is irreversible

steps towards statehood.

And in many ways, he cashed that shit out in the Saudi-French

initiative where he convinced the Saudis and the French that the response to

the Gaza War, which––really was a stress test to everyone of what happens if

you ignore this conflict for too long. And it's just impossible given the

peculiarities of this particular conflict.

He cashed that shit out on the Saudi-French initiative where he

received nine recognitions, including two UN Security Council permanent

members, and there was no annexation that was in response despite the fact that

the Israelis promised a response.

There wasn't because, you know, the Americans that were

convinced by their regionalized that wasn't relevant. So now President Abbas

looks at where he's got up to knowing that there's no one really to speak to in

Jerusalem, that the region wants this conflict to move on. The region wants to

move on.

He's got his recognitions that lock in the state of Palestine

within multiple different Western capitals that he's made sure that the

Israelis can't annex them out of existence and now ask himself, now what? Now,

you know, in the twilight of my presidency, what is it that I should be doing?

You know, I'm 90 years old.

I think that whereas the Palestinians have always had this

inverse power dynamic internationally, the, you know, the streets of the West

and in the academy, this and the international legal community and at the ICC

and at the ICJ, these huge amounts of support for their cause.

And really sort of eating the Israelis’ lunch on a power

dynamic when it comes to the actual implementation, there's this feeling like

no one's going to stop the Israelis anyway, and the Israelis will burn down all

international law to prevent it from happening.

Anyway. I think that in Ramallah they basically made the

decision that we've got as far as we can on an internationalization strategy.

We actually did very well. We've got ourselves back on the agenda. There's

nothing left to do. The Israelis proved in Gaza, there's no limit that they'll

stop and they'll go after everyone and they'll destroy until there's nothing

left to destroy.

And in that case, maybe it makes more sense to throw in with

the one world leader who's managed to restrain Israel, which was President

Trump. And what we need to do with that is work with him. Now, you know, they

don't want to be left with the deal of the century. And I think that what they

want to do is to try and demonstrate that they can be reasonable and rational,

and that the Israelis can't be reasonable and rational.

But for them to be able to demonstrate their reasonable and

rationality they need to be able to reform. So in many ways, they have put

their national self-determination in actuality, not in legality, but in

actuality on their ability to reform, which I'm sure will drive their

supporters internationally nuts.

But from them sitting in Ramallah watching settlements grow

every single day, they're like, that strategy hasn't done anything. And maybe

this one will work.

Will it, is the big question, because you are sacrificing

something that you truly controlled, which was your moral authority and legal

authority, in order to get into the role of, can we now trust world powers to

restrain Israeli action and to help us actually get somewhere better than where

our population has been?

And if all of these sort of man on the street––if you are

someone in Ramallah or you're someone in Hebron, or you're someone in, or you

are someone in Gaza. You want to see the Israeli killing stop and for your

dignity and rights to improve, will this now be a pathway for that to actually

move forward?

And it's a big question and it's a huge gamble, but I think

that if we don't want to see a return to just utter violence, we're going to

need to hope that this gamble works and work towards it. And in many ways, President

Trump, through this Board of Peace, takes on this mantle to do it.

Now, do you trust it? I don’t know. I don't. I don't know how

anyone could be certain, and I would argue, I don't know how you could be

certain in one way or the other. President Trump has demonstrated a complete

bucking of all orthodoxies when it comes to U.S. foreign policy and basically

global international policy in terms of what he did at the UN Security Council.

So the Palestinians have decided to change their tactics. Will

it work? I mean, Hamas had been continuing down a path of violent resistance as

we saw on October 7th, and we saw what the conclusion of that was. The Israelis

can be not just systemically but acutely, far more violent than you can be,

right?

And you can scream at the world to make them stop and this is

what they've got. But if you turn back to violence, the Trump administration

will allow the Israelis to do whatever they want. So that pathway has been shut

off. The international legal discourse of reached a point where the U.S.

doesn't care about international law, and the Russians clearly don't care about

international law. And you've lost two members of the UN Security Council.

You can hurt the Israelis internationally, but domestically,

they'll continue to destroy you. So then the question is, what's left? To sort

of throw yourself on the good graces of the Trump administration and hope that

works.

Hope isn't a strategy, but I think it's more than just hope.

I'd say, Scott, if this was just a Ramallah strategy and the rest of the region

wasn't with them, it would be incredibly stupid and very risky because the PA

and the Palestinians, just given their standing in Washington, don't have the

heft to move this themselves.

But if they're standing really with the Saudis, the Qataris,

the Turks, the Emiratis, the region as a whole, and they're like, look, Ramallah

is doing its best and they're not standing in the way and they're trying to

move forward, and you need to make sure that what happens in the West Bank

doesn't upset your signature achievement in Gaza, and that this can actually

lead forward to a political process if the Palestinians are reasonable, I think

it puts the pressure back onto Jerusalem to now come up with a policy towards

the Palestinians.

Because I'd argue that there hasn't been a policy towards the

Palestinians since the Second Intifada, for various different reasons. And now

as the Israelis go to an election, the coalition and the opposition needs to

develop a policy.

The coalition policy at this point is very clear: collapse the

PA.

I mean, it's not the official policy. The actual official

policy of this government is not to collapse the PA, but when you look at the Finance

Minister and what he's doing and his open stuff, and the National Security

Minister and the primaries, that seems to be where they're moving towards.

The opposition––of course, it's not popular to campaign on this––is

going to need to have a policy towards the Palestinians. And I'd say as my last

piece of a very long answer––I warned you this was a whole podcast––I'd argue

that for the Israelis, it actually takes on huge additional weight. Not just on

their relationship with the region, which, you know, they'll claim the Saudis

don't actually care. The Emiratis don't care.

I'd actually claim it takes on huge weight with their now

bilateral relationship with the United States. I think that we know that the

Democrats are going through a complete revolution vis-a-vis their relationship

with the state of Israel. And I'd claim that post-Trump MAGA world is also

going through an equal revolution.

We don’t know where it's going to, where it's going to land, okay.

As this relationship moves from a values relationship to an interest

relationship, what interest did the Israelis share with America that they could

offer vis-a-vis the region? And how long can they continue to maybe just be an

irritant if they're trying to dominate the region at the expense of other U.S.

allies like Saudi and Turkey? Can they find a way to coexist and co-do that?

And that requires them to have a policy towards the

Palestinians, so they can say what they are for when they speak to Democrats

and when they speak to whether it's America First or whatever, becomes the new

Republican ideology. What are they for when it comes to the Palestinians?

Because again, something we spoke about before President Trump

was inaugurated, but after he was elected, the Israeli right has misread the

American very badly. I think that they have assumed that they were anti-Palestinian,

they were fine with expulsion and everything else.

I think that the American right were no lovers of the PA or

like Palestinian nationalism, but were not Israeli supremacists, they weren't

Jewish supremacists.

You know, the nativist right is not Jewish supremacists. It's

white supremacists. And so I think that's been a big misreading, not just in

America, but also in, in Italy where you've got a right-wing prime minister who

is increasingly becoming more pro-Palestinian by the day and elsewhere.

So I think that as the Israelis reconstitute their analysis,

the need for them to have a policy towards the Palestinians becomes important

not just for their regional relationships, but for their most important

relationship vis-a-vis the United States. Because as every other country in the

world has tried to lessen their level of dependency on the U.S. when President

Trump came in knowing that everything is tradable, the Israelis up their level

of dependency, as we've seen with the Board of Peace and everything else.

So they're now stuck with significant more American

intervention in literally their backyard. And now they need to be able to

articulate a policy that they can sell to their population because without

that, they're adrift. And them being adrift by themselves can very quickly

transform into a real position of weakness in the region, where the region

chooses to move on with U.S. support and the Israelis are stuck where they are.

And I think that's really the challenge moving forward.

Scott R. Anderson: