Nathan Myhrvold on "Strategic Terrorism: A Call to Action" (Lawfare Research Paper Series)

A few weeks ago, I found myself at dinner in Seattle with a man named Nathan Myhrvold. Myhrvold, for readers who have never heard of him, is the founder and CEO of a company called Intellectual Ventures.

A few weeks ago, I found myself at dinner in Seattle with a man named Nathan Myhrvold. Myhrvold, for readers who have never heard of him, is the founder and CEO of a company called Intellectual Ventures.

A few weeks ago, I found myself at dinner in Seattle with a man named Nathan Myhrvold. Myhrvold, for readers who have never heard of him, is the founder and CEO of a company called Intellectual Ventures. He used to be the chief technology officer at Microsoft, and he's legendary as a polymathic mind---his serious interests include everything from academic paleontology to writing a multi-volume treatise on "Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking."

One of Myhrvold's interests is national security. The agenda item at dinner was a paper he had written some time earlier arguing, broadly speaking, that the United States is insufficiently focused on terrorism of a strategically-important magnitude---that is to say, nuclear and biological attacks. The paper had landed on my desk a couple of years ago, when David Kris---the former assistant attorney general for the National Security Division who is now general counsel at Intellectual Ventures---had sent it my way wondering whether as much of it rang true to me as rang true to him. It had never been published. And when I read it, that struck me as a shame---because a lot of it rings true, terrifyingly true.

Myhrvold is a highly-opinionated guy, and there's lots in this paper that people will disagree with. But there's also a core that strikes me both as undeniably correct and very important. I may be biased here; the paper has some pretty deep intellectual threads in common with work I have done on new technologies, violence, and security---a subject on which Gabriella Blum and I are currently finishing up a book. But I don't think anyone who looks squarely at the issues Myhrvold raises can reasonably emerge without real fear and without anxiety that our counterterrorism priorities are badly misaligned with the threats of greatest magnitude.

Over dinner, I suggested that Myhrvold let Lawfare publish the paper, entitled "Strategic Terrorism: A Call to Action," and he agreed.

I strongly recommend it.

Myhrvold's basic argument is that the United States is focused on stopping what he calls tactical terrorism---things like bombings---which can kill a bunch of people but which don't fundamentally threaten humanity. The trouble, he writes, is that "For the first time in human history, the curve of cost versus lethality has turned rapidly downward, falling many orders of magnitude in just a generation." The result, as I have also argued, is that someone truly devoted to maximizing lethality can today have impacts of a strategic magnitude: "[Theodore] Kaczynski [better known as the Unabomber] certainly had enough brains to use sophisticated methods, but because he opposed advanced technology, he made untraceable low-tech bombs that killed only three people. A future Kaczynski with training in microbiology and genetics and an eagerness to use the destructive power of that science could be a threat to the entire human race.”

Yet strangely, while officials are certainly aware of this problem, our counterterrorism efforts are not focused around it. “[W]ho is the most senior government official whose full-time job is defending the United States against strategic terrorism?" he asks:

A few weeks ago, I found myself at dinner in Seattle with a man named Nathan Myhrvold. Myhrvold, for readers who have never heard of him, is the founder and CEO of a company called Intellectual Ventures. He used to be the chief technology officer at Microsoft, and he's legendary as a polymathic mind---his serious interests include everything from academic paleontology to writing a multi-volume treatise on "Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking."

One of Myhrvold's interests is national security. The agenda item at dinner was a paper he had written some time earlier arguing, broadly speaking, that the United States is insufficiently focused on terrorism of a strategically-important magnitude---that is to say, nuclear and biological attacks. The paper had landed on my desk a couple of years ago, when David Kris---the former assistant attorney general for the National Security Division who is now general counsel at Intellectual Ventures---had sent it my way wondering whether as much of it rang true to me as rang true to him. It had never been published. And when I read it, that struck me as a shame---because a lot of it rings true, terrifyingly true.

Myhrvold is a highly-opinionated guy, and there's lots in this paper that people will disagree with. But there's also a core that strikes me both as undeniably correct and very important. I may be biased here; the paper has some pretty deep intellectual threads in common with work I have done on new technologies, violence, and security---a subject on which Gabriella Blum and I are currently finishing up a book. But I don't think anyone who looks squarely at the issues Myhrvold raises can reasonably emerge without real fear and without anxiety that our counterterrorism priorities are badly misaligned with the threats of greatest magnitude.

Over dinner, I suggested that Myhrvold let Lawfare publish the paper, entitled "Strategic Terrorism: A Call to Action," and he agreed.

I strongly recommend it.

Myhrvold's basic argument is that the United States is focused on stopping what he calls tactical terrorism---things like bombings---which can kill a bunch of people but which don't fundamentally threaten humanity. The trouble, he writes, is that "For the first time in human history, the curve of cost versus lethality has turned rapidly downward, falling many orders of magnitude in just a generation." The result, as I have also argued, is that someone truly devoted to maximizing lethality can today have impacts of a strategic magnitude: "[Theodore] Kaczynski [better known as the Unabomber] certainly had enough brains to use sophisticated methods, but because he opposed advanced technology, he made untraceable low-tech bombs that killed only three people. A future Kaczynski with training in microbiology and genetics and an eagerness to use the destructive power of that science could be a threat to the entire human race.”

Yet strangely, while officials are certainly aware of this problem, our counterterrorism efforts are not focused around it. “[W]ho is the most senior government official whose full-time job is defending the United States against strategic terrorism?" he asks:

The steps necessary to prevent nuclear and biological terrorism are qualitatively different from those needed to plug the holes that allowed 9/11 to happen. Yet our military forces and government agencies seem not to recognize this difference. Nearly all of their personnel and resources are focused on the immediate problems posed by tactical issues in Afghanistan and by low-level terrorism directed at the United States.Myhrvold proposes a comprehensive reordering of security priorities:

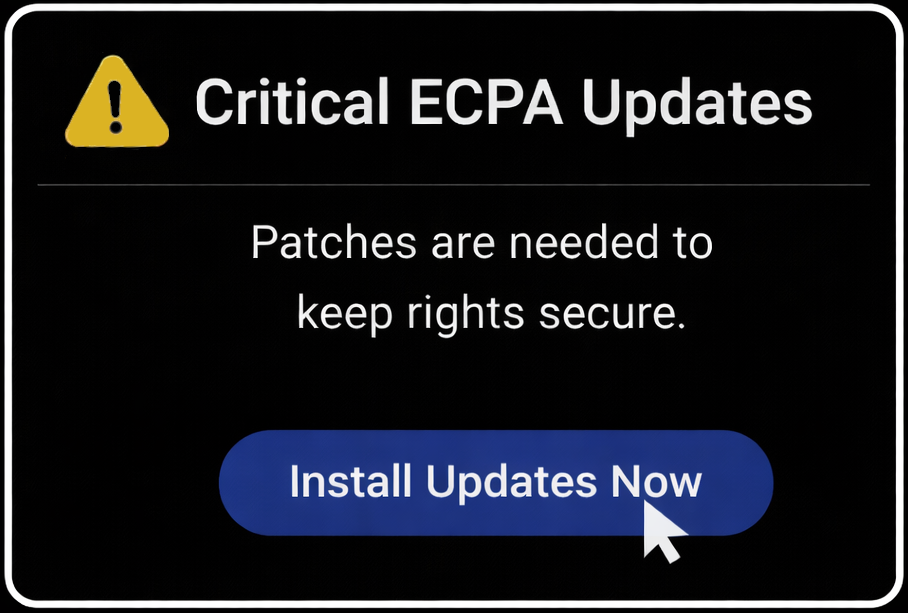

The only way to change this situation is to forge a comprehensive plan for research, development, and deployment of technologies to detect, to cure, or to prevent a biological attack. (Similar plans need to address nuclear and other possible varieties of strategic terrorism, although we will most likely be able to draw on existing work more directly to thwart those threats.)And part of that, he argues---in a section of the paper sure to raise eyebrows---is facing squarely and in a non-romantic way civil liberties questions to which we do not normally apply cold-blooded cost-benefit analysis:

Is the cost to society in lives really worth more than the cost of constraints on civil liberties? . . . . These are very serious issues that need to be weighed carefully and rationally, but Americans tend to overreact from emotion and lurch from one extreme to another. During peacetime, we expand rights steadily. Yet when the chips are down, we have routinely violated those rights in ways that were not simply unconstitutional but also ineffective and most likely unnecessary.It's a deeply challenging read---written in layman's terms that anyone can understand yet with enormous technical sophistication, a deep sense of the history of American security efforts, and a savvy about the way government operates that makes Myhrvold's bureaucratic arguments depressingly cogent. Here's the introduction:

Technology contains no inherent moral directive—it empowers people whatever their intent, good or evil. This fact, of course, has always been true: when bronze implements supplanted those made of stone, the ancient world got swords and battle-axes as well as scythes and awls. Every technology has violent applications because that is one of the first things we humans ask of our tools. The novelty of our present situation is that modern technology can provide small groups of people much greater lethality than ever before. We now have to worry that private parties might gain access to weapons that are as destructive as—or possibly even more destructive than—those held by any nation-state. A handful of people, perhaps even a single individual, now has the ability to kill millions or even billions. Indeed, it is perfectly feasible from a technical standpoint to kill every man, woman, and child on Earth. The gravity of the situation is so extreme that getting the concept across without seeming silly or alarmist is challenging. Just thinking about the subject with any degree of seriousness numbs the mind. Worries about the future of the human race are hardly novel. Indeed, the notion that terrorists or others might use weapons of mass destruction is so commonplace as to be almost passé. Spy novels, movies, and television dramas explore this plot frequently. We have become desensitized to this entire genre, in part because James Bond always manages to save the world in the end. Reality may be different. In my estimation, the U.S. government, although well-meaning, is unable to protect us from the greatest threats we face. The other nations of the world are also utterly unprepared. Even obvious and simple steps are not being taken. The gap between what is necessary and what is being contemplated, much less being done, is staggering. My appraisal of the present situation does not discount the enormous efforts of many brave men and women in law enforcement, intelligence services, and the military. These people are doing what they can, but the resources that we commit to defense and the gathering of intelligence are mostly squandered on problems that are far less dangerous to the American public than the ones we are ignoring. Addressing the issue in a meaningful way will ultimately require large structural changes in many parts of the government. So far, however, our political leaders have had neither the vision to see the enormity of the problem nor the will to combat it. These weaknesses are not surprising: bureaucracies change only under extreme duress. And despite what some may say, the shocking attacks of September 11th, 2001, have not served as a wake-up call to get serious. Given the meager response to that assault, every reason exists to believe that sometime in the next few decades America will be attacked on a scale that will make 9/11 look trivial by comparison. The goal of this essay is to present the case for making the needed changes before such a catastrophe occurs. The issues described here are too important to ignore.

Benjamin Wittes is editor in chief of Lawfare and a Senior Fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution. He is the author of several books.