The Situation: No, Don’t Release the Epstein Files

I have a better idea.

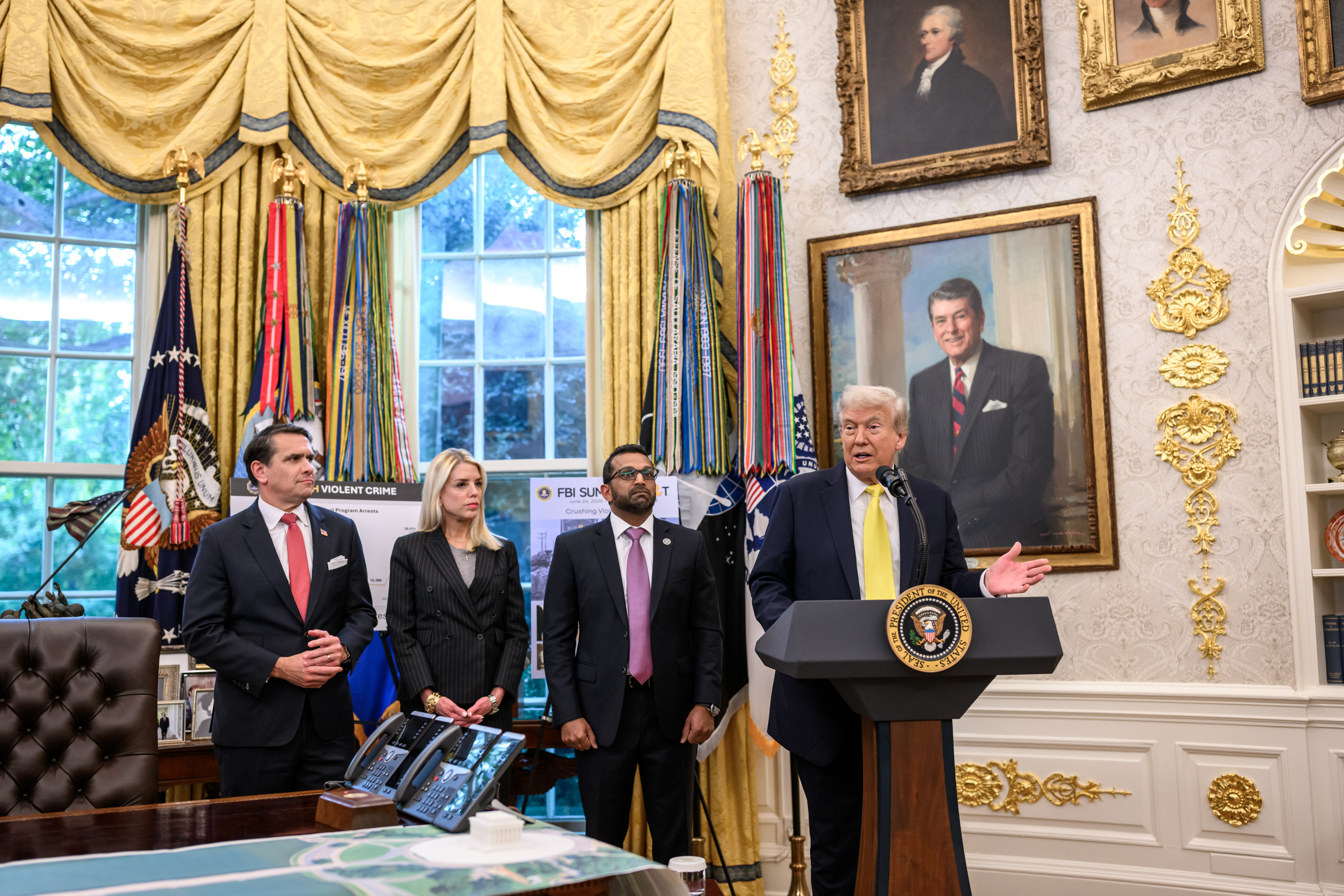

The Situation on Monday mocked the Real Housewives of the Department of Justice.

All of a sudden, it seems like everyone is calling for the release of the Epstein files. The MAGA movement is angry at President Trump and Attorney General Pam Bondi for not coming through for them and delivering the cabal of rich pedophiles who benefited from relationships with Epstein.

Democrats and other Trump opponents, smelling blood in the water, have joined the calls for transparency on the theory that they might hoist Trump and his attorney general on their own conspiracy-packed petard.

Allow me a moment’s dissent: Have you all lost your minds?

Should the FBI and the Justice Department release willy-nilly their investigative files into a major child-exploitation and human trafficking case involving a large number of victims—given that truly vile conduct directed at them, and an untold number of witnesses who may be wholly innocent of wrongdoing, is likely to be unleashed?

The question answers itself.

For one thing, at least some of the information in the so-called Epstein files is likely grand jury information—that is, information protected by Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure—or otherwise protected by court seals. It is illegal to release this material. It’s not a choice the attorney general gets to make: Should I dump all this information into the public domain? She can’t. She shouldn’t. And if she does, she should go to jail.

Attorney General Bondi should resign if she was lying when she declared that she had Epstein’s client list on her desk—something the FBI now says does not exist. If she simply misspoke, she did so recklessly and stupidly and should probably resign anyway. But the solution is not a data dump of material, much of which is properly protected by federal law.

Even among the materials that are not protected by court seals, the Epstein files necessarily contain a wide range of information about victims. Are people seriously calling for this material to be dumped into the public’s hands?

And what about material collected from and about innocent people? All major investigations do this. Are people really suggesting that people giving evidence against Epstein should have their lives turned upside down by being effectively doxxed by the FBI?

There are good reasons, a lot of them, why federal law enforcement doesn’t do investigations in public and why it doesn’t release the fruits of its investigative efforts as a matter of course. The case of a serial predator whose misconduct touched a thousand victims and hundreds of other people is no time to throw away rules and civil liberties protections that are designed to prevent law enforcement from being an instrument of indiscriminate shaming and public exposure.

Even the so-called Epstein client list, which Bondi now says does not exist, would be a dicey thing to make public if it did. Imagine a list, in a little black book, labeled “Clients” that is somewhere in the Epstein files and has a list of names in it. Imagine that this list contains all the people you would want to be on it—that is, from whatever political persuasion you come from, it is the list that would vindicate you maximally were it to become public.

Sure, you might imagine such a list to represent the list of powerful men to whom Epstein was providing underage or trafficked women for sexual exploitation. But Epstein was also a financier who had clients. How would you know, absent someone’s testimony, that it wasn’t just a list of financial clients? How would you know that it wasn’t a list of people he aspired to have as clients?

I know what you’re thinking: But how are we going to tamp down all of these conspiracy theories without more disclosure?

The answer is that we’re not. No amount of disclosure will tamp down the conspiracy theories. For all of the reasons mentioned above, any document dump would be rife with redactions. Documents would be withheld. Names would be blacked out. Indeed, even the proponents of greater transparency in Congress leave room for such things in the name of protecting victims.

But the conspiracy theories will immediately reassemble themselves around any redactions or withheld materials. You cannot sate the conspiracy beast with disclosure. Its appetite is totally unquenchable.

It just will not do to insist that this case is different. Yes, this case is different because it involves a serial predator who mingled among the political and other elites. The Jan. 6 case is different because it involved an insurrection inspired by the president. And the 9/11 case is different because it involved planes flying into buildings. Every case is unique, and we have rules so that we don’t do things differently when we really want to screw the friends of a defendant or we really want to make a loud statement about how heinous a crime may have been.

So, no, don’t release the Epstein files. Not even if you’re sure they’ll humiliate the right person or people and class or cabal. It’s not the way our system works. And that’s a good thing.

Having said that, let me say that there are, by my count anyway, four discrete areas in which the public might benefit from greater disclosure on the Epstein case. And there are at least two lawful and appropriate ways to effectuate this disclosure:

First, to the extent that there is undisclosed information about the circumstances of Epstein’s death, a death in custody should always be investigated fully and completely, and the fruits of that investigation should be made public. I have zero reason to believe, to be clear, that Epstein died by any hand other than his own, but we should err on the side of maximum disclosure of this sort of thing. The Justice Department inspector general issued a report on this subject back in 2023. If members of Congress have further questions on the subject, a congressional investigation is a perfectly appropriate means of addressing them and making public any material still under wraps.

Second, if there is evidence of Epstein providing trafficked or minor women for sex to any person, I have no trouble with this evidence becoming public. But it should not simply be released by the Justice Department, for all the reasons described above. It is, however, perfectly appropriate for Congress—which has shown itself adept at conducting major investigations of late for the purposes of telling stories to the public of matters of national import—to look into the matter and seek the department’s cooperation in doing so. How much it would get is unclear, but congressional committees have done admirable work over the past few years on Russian interference in the 2016 election, on the “perfect” phone call, and on the Jan. 6 insurrection. A look back at the Epstein saga that sought to name names of those who exploited young women would be tawdry, but it wouldn’t be inappropriate.

Third, there are certain individuals whose relationship with Epstein demands a degree of explanation. Democrats want clarity on Epstein’s relationship with President Trump. Many Republicans want a probe into his ties to former President Bill Clinton. A congressional probe could be specifically charged with examining Epstein’s relationship with presidents—or major political figures—of both parties.

Finally, fourth, there is a legitimate set of questions remaining about the conduct of the investigation of Epstein, both the original investigation in Florida and the subsequent one after it was revived during the first Trump administration. Some of this subject was covered by an Office of Professional Responsibility report from 2020. But not all of it was. In particular, the question of why the investigation never progressed beyond Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell—particularly in combination with Epstein’s death and the sweetheart deal he received in his earlier prosecution—has helped drive the belief that the man had some sort of protection from on high.

A thorough review of the matter would actually be a helpful thing, less by way of rebutting conspiracy theories than by way of telling a story that really does raise questions about how Epstein avoided accountability for so long and how those who cavorted with him have avoided it to this day. The jurisdictional lines here are complicated, but some combination of an inspector general investigation (covering the investigative side), an OPR investigation (covering the prosecutorial side), and a congressional investigation covering the wide-arch policy questions and history could be constructive here.

What the world doesn’t need is a document dump.

So, no, don’t release the Epstein files. Let’s study the Epstein saga rigorously instead.

The Situation continues tomorrow.