Offensive Cyber Operations and Combat Effectiveness After Ukraine

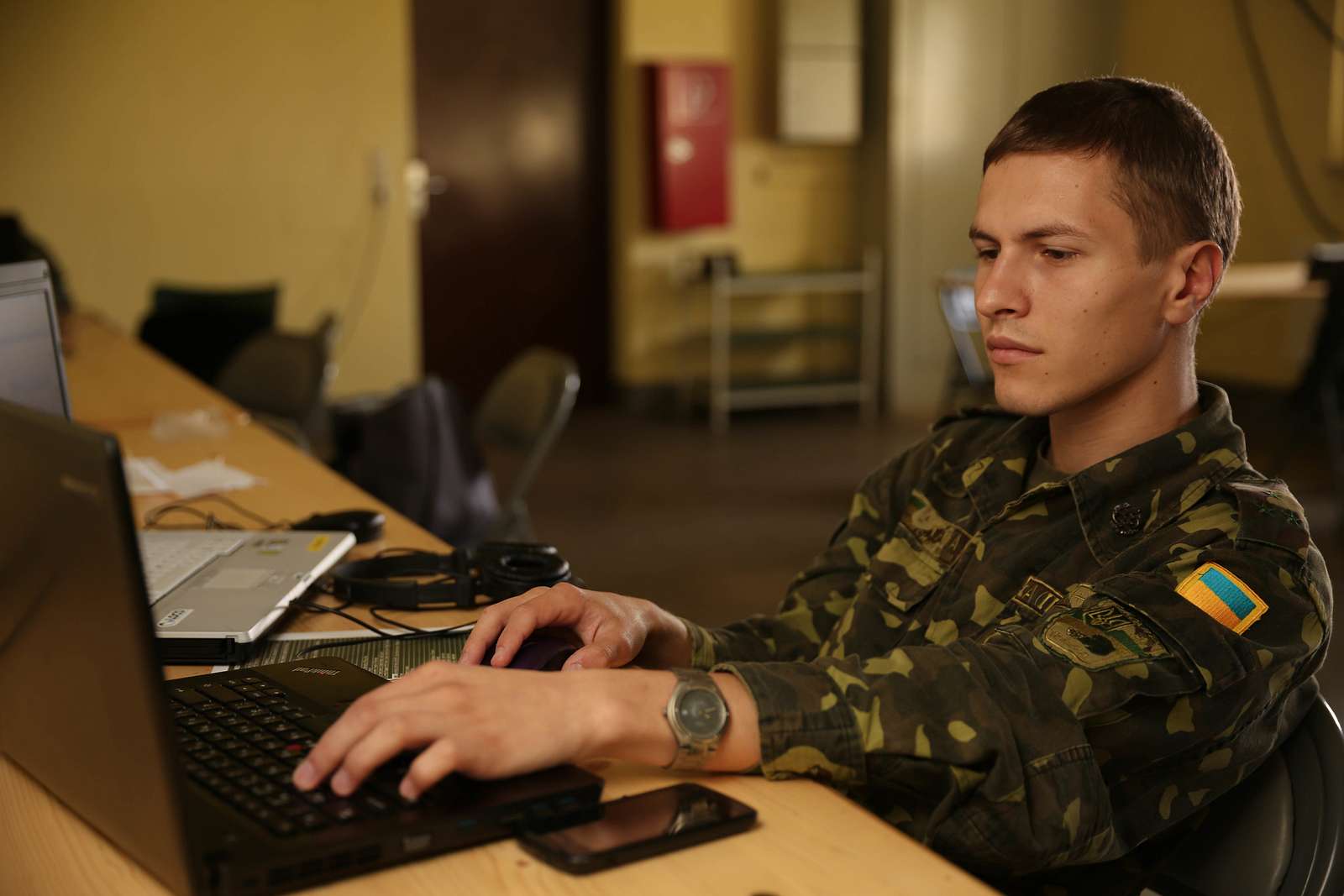

On March 4, one day after President Trump announced the temporary suspension of U.S. military aid to Ukraine, nine young Ukrainian citizens were awarded the Order of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. These Ukrainians were not muscular, battle-scarred veterans—they were civilians. More specifically, they were members of Laska (“weasel” in English), a group of Ukrainian hacktivists, who received the highest military award the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (GUR) has ever given out to civilians for “their skillful actions in [Russia]’s cyberspace [which] significantly reduced the capabilities of the military-industrial complex of the aggressor state of [R]ussia, as well as provided critical information.”

As Western democratic nations have been promoting international law and the development of “responsible” behavior in cyberspace, Ukraine’s use of offensive cyber operations has broken Western taboos and legal limitations. Kyiv’s “quantity over quality” approach in cyberspace is casting a wide net of targets to achieve specific strategic goals. And Ukraine has not shied away from attacking civilian infrastructure and militarizing non-state actors, including domestic hacktivists and international volunteers. Russia has subsequently adapted—not always with success. Ukraine’s achievements in the cyber domain show that, while the enduring moral desire to legally bind states to behave responsibly in cyberspace and adhere to international law is certainly commendable, these ambitions stand in stark contrast to the realities of contemporary digital conflict.

“Responsible” Cyber Operations

Rheinbach is a small town of just 26,000 inhabitants, located roughly 20 kilometers southwest of Bonn, the former capital of West Germany. Yet this sleepy town houses the Cyber Operations Center or ZCO, the offensive cyber wing of the German Armed Forces. It was from here that ZCO’s predecessor organization, the Computer Network Operations Group (CNO), conducted Germany’s first known offensive cyber operation in 2015. Very little is publicly known about the activities of the ZCO. So it was surprising that, on July 8, the Bundeswehr’s official website published a short interview with Capt. Sven Janssen, the commander of the ZCO.

Janssen emphasized that the ZCO is complying with national and international law, adheres to the laws of armed conflict, and conducts operations in a precise and controlled manner. Noting that “every planned measure is carefully examined and documented; the legal assessment is an integral part of the work at the ZCO Cyber Operations Center.” That Janssen felt the need to stress this point reflects a political discourse in Europe that generally views offensive cyber operations as legally suspicious, potentially destabilizing, and morally repugnant given their clandestine and covert nature. Indeed, over the years Europe’s engagement in the UN discussions on responsible behavior in cyberspace, coupled with its continuous calling out of Russian and Chinese malicious cyber campaigns during peacetime, has fostered a normative stance on the continent that regards offensive cyber operations as politically impermissible—potentially even during wartime. Europe’s growing focus on hybrid warfare and the state of “unpeace” has paradoxically reinforced this perception due to persistent escalation fears and the uncertainty over the threshold of armed conflict.

Back in 2019, Elanor Boekholt-O’Sullivan, then-commander of the Dutch Defense Cyber Command, noted in an interview that “lawyers are blocking the cyber experts’ imagination, improvisation, and creativity which are necessary for future cyber scenarios” and that “cyber offensive operations are very difficult to execute in the current political climate.” Writing for Binding Hook in July 2024, an anonymous European intelligence official even warned of an increase in idealistic legalism—i.e. “a one-sided view of the intelligence and cyber domains that sees law as an ideal governance tool in shaping cyberspace capabilities.” The intelligence officer underscored that this development “is increasingly constraining our ability to manoeuvre and contest our adversaries in and through cyberspace.”

Despite these concerns, the U.K. government fully endorsed the term “responsible and democratic cyber power” in 2021 to distinguish its own offensive cyber operations from the behavior of Russia and other so-called “irresponsible” states. Notably, the term “responsible” applies largely to behavior in peacetime—not in wartime—that leans heavily into the idea of promoting a free, open, peaceful, and secure cyberspace. It thus encapsulates existing international law as well as 11 nonbinding norms of responsible state behavior that were endorsed by the UN in 2021. This includes, for example, the norms that states should refrain from conducting cyber activities that damage critical infrastructure (Norm F) and that states should cooperate to combat criminal and terrorist activities online (Norm D).

The U.K.’s National Cyber Force (NCF)—a partnership between the U.K. Ministry of Defense and the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ)—subsequently also published a guidance paper in April 2023 titled “Responsible Cyber Power in Practice.” In the paper, the NCF publicly committed itself to upholding strong legal and ethical frameworks, ensuring rigorous domestic oversight and accountability, and following structured planning processes so that U.K. cyber operations are accountable, precise, and carefully calibrated. Notably, however, the NCF has never conducted an offensive cyber operation in peacetime, perhaps reflecting just how politically sensitive and legally boxed in its mission space remains.

In fact, to date, the only publicly known offensive cyber operations the NCF and ZCO have conducted occurred in a wartime counterterrorism context. In 2015—when German soldiers were still deployed in Afghanistan—the ZCO breached an Afghani telecommunications provider to track the mobile phone of a hostage negotiator. And in June 2017, then-U.K. Defense Secretary Sir Michael Fallon revealed that “we are now using offensive cyber routinely in the war against Daesh, not only in Iraq but also in the campaign to liberate Raqqa and other towns on the Euphrates. Offensive cyber there is already beginning to have a major effect on degrading Daesh’s capabilities.”

Instead of foregrounding responsibility in cyberspace and questioning the use of offensive cyber operations at every turn, Europe must be willing to learn, evolve, and adapt to the new realities of digital conflict—a battlespace that cuts across traditional categories of peace and wartime. And there is no better classroom on how to leverage offensive operations—and become “responsibly irresponsible” in cyberspace—than the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Quantity Over Quality

If there is one cyber warfare lesson Western militaries should take from the three and a half years of cyber warfighting in Ukraine, it is that the effectiveness of individual offensive cyber operations hinges on the ability to maintain a steady operational tempo throughout the entire course of a war. In the long run, quantity matters more than quality in cyberspace.

The reasons for this combat dynamic are rather simple. First, cyber defenders naturally become better over time as they adapt to adversarial tactics, thinking, and mission goals. Second, throughout the course of a war, important digital assets become increasingly hardened, making it more difficult for an adversary to maintain a foothold in them. Third, the more time and resources an adversary must spend on breaching one target, the less time and resources they can spend on breaching others. For the attacker there are three general ways to prevent a slowdown in operational tempo: increase the overall personnel and resources dedicated to a specific cyber mission theater; shift personnel and resources from one theater to another; or widen the pool of targets within a theater to include less important but weaker protected digital assets.

In Ukraine, this combat dynamic has clearly unfolded over time. Moscow is constrained in how much offensive cyber capacities it can dedicate exclusively to the Ukrainian war theater. At the same time, it must maintain a cyber mission footprint in North America, Western Europe, Central Asia, and other regions that are relevant to its long-term national security posture. By contrast, Kyiv can dedicate all of its attention to run operations against Russia’s entire digital infrastructure. As far as open source is concerned, not a single Ukrainian cyber operation has been conducted against assets in Iran, North Korea, or China over the past three years. The Ukrainians have also not emulated the Russian approach of running destructive cyber campaigns against high-value communication infrastructure assets, such as Moscow did when it took out Viasat and Kyivstar in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Instead, Ukraine has cast a much wider net, which—with a few exceptions—deems every civilian and government asset in the .ru domain space a permissible target, whether they are banks, pharmacies, fast food delivery services, or theaters. Europe’s current political discourse and interpretation of the law of armed conflict would paint the targeting of these civilian assets as irresponsible, impermissible, and likely unlawful as they violate the principle of distinction and military necessity.

Kyiv has not wasted time and bureaucratic resources to set up its own military cyber command—and legal department—while fighting for the nation’s survival. Similarly, it has not significantly ramped up the training of offensive cyber operators in-house, due to more pressing capacity demands on the kinetic battlefield. Instead, the Ukrainian armed forces and intelligence services made the distinct choice to outsource and partner with volunteers abroad and hacktivists at home to steer, support, and help conduct offensive cyber operations against Russia’s digital infrastructure.

Militarizing “Non-state” Actors

In April 2024, Michigan-based U.S. hacktivist Kristopher Kortright spoke to the BBC about an award of gratitude he received by the then-commander of Ukraine’s Air Assault Forces. Kortright’s international hacktivist group Team OneFist likely received the award for hacking Russian surveillance cameras and providing intelligence on Russian troop and equipment movements directly to the Ukrainian military. The award was probably the first time that a military commander in an ongoing armed conflict has officially thanked an international hacking group for its activities. Roughly one year later, in March 2025, Ukraine’s military intelligence service would award the Order of Bohdan Khmelnytsky to the Ukrainian hacktivist group Laska, whose exact operations remain opaque.

To this day, it is unknown whether the Ukrainian armed forces or the intelligence services themselves maintain their own offensive cyber units. Western governments and cyber threat intelligence companies have generally refrained from publicly speaking or releasing any reports on Ukrainian cyber threat actors. But it is known that the cooperation between Ukraine’s military intelligence service and hacktivists has been ongoing for several years. In 2024 and 2025, GUR teamed up with the now-125,000 member-strong crowdsourced IT Army of Ukraine to conduct distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against civilian targets including Russian banks, internet service providers, and the digital infrastructure of the COS-project (a Russian community effort to develop customized firmware for drone controllers and screens, and to provide Russian-language support). According to GUR’s official website, the COS-project was targeted because its “software is used by [R]ussians to reflash DJI drones to meet the needs of combat operations.”

Further, in early July, Ukraine’s military intelligence service teamed up with the hacking group Black Owl (BO) and the Ukrainian Cyber Alliance to run a destructive campaign against Russian drone supplier Gaskar. The Ukrainian Cyber Alliance was founded in 2016 and has been working sporadically for the Ukrainian armed forces and intelligence services. The BO Team emerged on Jan. 26, 2024, nearly two years into the war. Interestingly, the BO Team’s first-ever destructive campaign was announced on GUR’s official website—two days before the group established its own Telegram channel. GUR’s relationship with the BO Team is quite special; they might even be part of GUR itself. According to the BO Team’s Telegram Channel, their attack on Gaskar resulted in the deletion and exfiltration of 47 terabytes of data and 10 terabytes of backups. They also disabled Gaskar’s production line by wiping four ESXi platforms, 26 virtual servers, 200 timing stations, and 20 MikroTik routers.

Moscow has recently begun to emulate Kyiv’s approach of militarizing domestic hacktivists and international volunteers. In the beginning of the invasion, Moscow’s war plans did not include Russian hacktivists at all. Russian ransomware groups, for example, have not discernably engaged in the war in Ukraine to this day. This is partly due to the Federal Security Service’s (FSB’s) unprecedented arrest of 14 members of the REvil ransomware group a month prior to the invasion, and the implosion of Conti—the largest ransomware group at the time—shortly after the invasion. Conti’s eventual demise was caused by the infighting of its Russian and Ukrainian members, which resulted in the leak of thousands of chat messages that revealed the group’s inner workings.

Russian hacktivist groups, including KillNet and NoName057(16), participated in the war tangentially by running independent DDoS campaigns against websites in countries that are supporting Ukraine. Since November 2023, NoName057(16) has run 14 DDoS campaigns against more than 250 government and company websites in Germany. Notably, on July 16, a joint international operation coordinated by Europol and Eurojust took down NoName057(16)’s DDoS infrastructure in Europe. The operation led to two arrests, seven arrest warrants, and 24 house searches in Czechia, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain. Five Russia-based NoName057(16) members were subsequently included in Europol’s Most Wanted list. German law enforcement is estimating that NoName057(16)’s support network consists of more than 4,000 users and hundreds of servers around the globe.

Besides these cases, however, Russian intelligence services have largely refused to integrate hacktivists in their operations. Instead, the services have created their own fake hacktivist cyber personas, including XakNet, Solntsepek, and the Cyber Army of Russia Reborn, to cloak their cyber operations behind the veil of hacktivism. It remains unclear why Russian intelligence opted to go this cumbersome route. The decision might have stemmed from a combination of factors, including recognizing the strategic value of hacktivism in shaping the war’s online narrative; creating an experimental space to sow confusion among defenders; and a sense of professional pride and reluctance to collaborate with hacktivists, low-level cybercriminals, and amateurs in times of war.

Matters changed significantly in 2025. For most of the war in Ukraine, KillNet has been known for conducting noisy DDoS campaigns and being intermittently banned from Telegram. The group’s DDoS campaigns never achieved any discernable impact on the kinetic battlefield, which puts them squarely into the hacktivist category. However, on May 22, KillNet allegedly gained access to a Finnish-made Sensofusion platform used by the Ukrainian armed forces. KillNet allegedly extracted the location data of tens of thousands of Ukrainian drones, including their GPS coordinates, model, and drone-ID. The group then forwarded the location data to Russia’s 88th Reconnaissance Assault Brigade “Española,” which in turn conducted drone strikes against the Ukrainian assets.

Since May 2025, KillNet has allegedly conducted other battlefield-relevant operations, including breaching Ukraine’s unified situational awareness platform DELTA and breaching an online platform belonging to U.S. satellite imagery company Maxar. It is highly likely that the Maxar breach was a false flag and never occurred. As of this writing, it is still unknown whether the Sensofusion breach and the DELTA breach occurred. Neither Sensofusion nor the Ukrainian armed forces has commented publicly on the matter.

The Success of the Ukrainian Model

Over the years, Russia’s way of fighting in cyberspace has undergone several strategic shifts due to Moscow’s changing intelligence needs and Kyiv’s evolving defensive posture. In 2022, Ukraine’s State Service for Special Communications and Information Protection (SSSCIP) recorded a combined 997 critical and high-severity incidents. By the end of 2023, that number dropped to 367. For the first half of 2024, the number of high-severity incidents stands at a mere 48—which is a 95 percent decrease compared to 2022. The shifting tide was notably felt in the media coverage about Ukraine as well. The last reported destructive Russian cyber operation that successfully took down a major Ukrainian company was Sandworm’s month-long infiltration of Kyivstar in December 2023. As far as statistics go, the numbers seem to indicate that Ukraine’s cybersecurity and defense posture has successfully adapted to the Russian threat over time.

Ukraine’s success has likely forced the Russians to adjust their overall strategy. According to the SSSCIP, in 2023 Russia shifted “from the destruction of infrastructure of ISPs, ministries, and government bodies to securing footholds and covertly extracting information, using cyber elements to gather feedback on the outcomes of their kinetic strikes. […] In 2024, [SSSCIP] observe[d] a pivot in their focus toward anything directly connected to the theater of war and attacks on service providers.”

What the SSSCIP’s data also reveals is that the overall number of cyber incidents increased from 1,079 in the first half of 2023, to 1,463 in the second half of 2023, to 1,729 in the first half of 2024. That is a 60 percent growth over 12 months. This expansion likely indicates that Russian cyber actors are going after a much broader set of targets to extract battlefield-relevant intelligence. As the SSSCIP notes, “in 2022 […] enemy hackers targeted organizations with evident flaws in cybersecurity, vulnerabilities, and opportunities they could easily exploit. […] In 2024 […] hackers are no longer just exploiting vulnerabilities wherever they are but are now targeting areas critical to the success and support of their military operations.” Despite the overall increase and changes in tactics, Moscow still must contend with a capacity ceiling that will naturally limit the quantity of operations they can run in cyberspace at any given point in time. Where exactly that ceiling is remains to be seen; Moscow’s cooperation with hacktivists can push the ceiling further up.

Responsibly Irresponsible

It is unknown how exactly Western militaries plan to fight against peer-competitors in cyberspace. It is equally unknown whether there have been any discussions within NATO or the individual member states on how to maintain cyber operational tempo during a year-long kinetic war. Curiously, the way NATO would likely choose to fight in cyberspace seems much more aligned with how the Russians had been operating until early 2025. NATO member states will highly likely go after adversarial communication infrastructure bottlenecks in the run-up to a kinetic campaign—the same way Russia did when it took out 30,000 Viasat modems on Feb. 24, 2022. NATO member states will likewise shift from the initial destruction of internet service providers and government networks to running operations that are supporting its kinetic campaigns. All of these operations will be in line with the law of armed conflict. That being said, NATO members will likely refrain from outsourcing offensive cyber operations and intelligence collection efforts to hacktivists and volunteers around the globe, as this would create legal and organizational friction.

However, given the difficulties that Russian offensive cyber operations have been facing, it may be wise for Western governments to learn from Kyiv and reconsider their ongoing emphasis on the laws of armed conflict, moving away from the idea of “responsibility.” To some degree, this policy shift has already occurred, as Western governments have remained silent on Ukrainian offensive cyber operations—and might even be tacitly supporting them.

But Democratic governments—particularly those in Europe—will have a hard time emulating Kyiv’s approach due to persistent political beliefs: that Western governments will naturally fight from a position of dominance where there is no need to exploit every possible advantage in cyberspace to hurt an adversary; that offensive cyber operations will adhere to strict domestic oversight, accountability, and international legal frameworks, even when adversarial campaigns do not; and that Western governments will be able to maintain a steady tempo in cyberspace throughout the entire war.

Over the past three years, Kyiv has shown the world a different way forward as it has mastered the art of being “responsibly irresponsible” in cyberspace by militarizing hacktivists, university students, and the IT community abroad and at home. Western governments may want to reflect on Ukraine’s lessons now, because they will likely be on the receiving end of this new warfighting style in the future.

First—whether it is banks, internet service providers, supermarkets, or online retail stores—adversarial civilian infrastructure is too irresistible not to target in cyberspace. Even minimal disruptions can assist in the economic fight against an adversary. Second, whether governments want it or not, hacktivists and volunteers will conduct their own cyber operations during wartime. Democratic governments can choose to ignore them, or they can actively support, incorporate, and direct them to fill capacity gaps and intelligence needs. Third, the volume of offensive cyber operations cloaks the tempo and effectiveness of individual operations. In other words, not every offensive cyber operation has to be executed quickly, reliably, and effectively if the overall volume pressures defenders to begin with. Fourth, not everything in cyberspace must be real. Wrongful self-attribution or claims that a cyber operation occurred—even though it has not—can help shape the news cycle, seed doubts internationally, and create morale-boosting effects at home. And fifth, ethics and international law are not static nor absolute in cyberspace, requiring constant reevaluation and reframing by governments.

Democratic governments, particularly those in Europe, would do well to remember that becoming a “responsible cyber power,” and strengthening norms and international law in cyberspace, are means to an end—global stability—and not goals in and of themselves. Militaries must continually adapt to enhance their combat effectiveness to win wars whenever they come knocking. In an era of great power conflict, being “responsibly irresponsible” could be the necessary ingredient to accelerating operational tempo, fostering innovation, and strengthening cooperation in cyberspace. Everything else might just be politics from a bygone age.