Recent African Court Ruling Spells Trouble for Rusesabagina and Rwanda

A recent African Court decision suggests trouble for human rights icon Paul Rusesabagina and the rule of law in Rwanda and the rest of Africa.

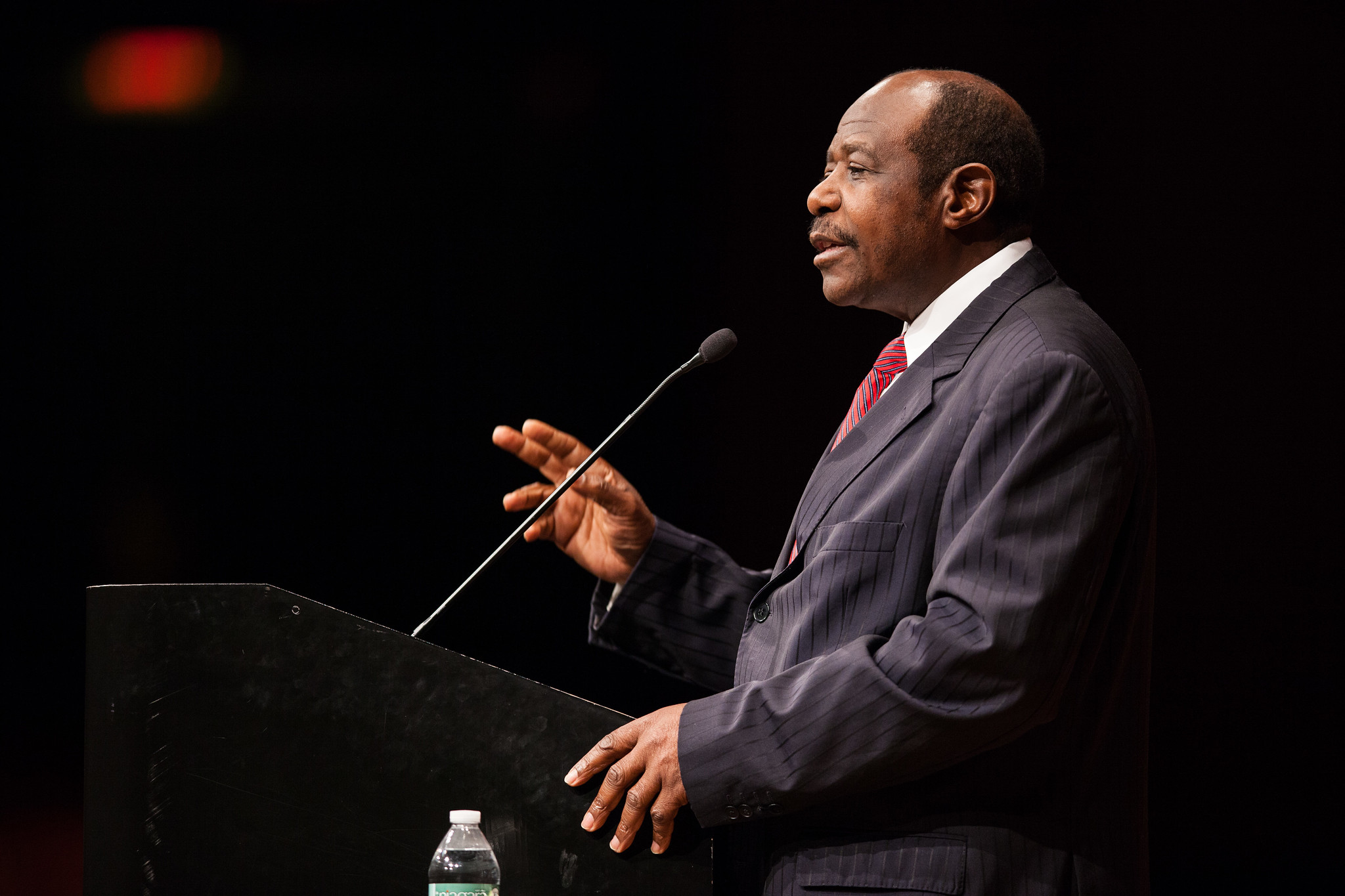

Portrayed as a hero in the 2004 Oscar-nominated film Hotel Rwanda, Paul Rusesabagina has recently been charged with terrorism in Rwanda, sparking international outrage. Rwandan authorities arrested Rusesabagina in August 2020 after he fell victim to an elaborate ruse organized by the country’s spy chief. The European Union and various human rights organizations have condemned the operation as a forced disappearance and accused Rwanda of committing numerous fair trial rights violations since his trial began in February. A bipartisan group of more than three dozen members of Congress pleaded for the humanitarian release of Rusesabagina, a 66-year-old cancer survivor who also suffers from a heart condition and hypertension. President Biden’s State Department has also announced that it is engaging with Rwandan leaders to ensure a fair judicial process.

Yet even as the ongoing trial of Rusesabagina has attracted substantial attention, a consequential decision by the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights has received scant focus in the Western media. Léon Mugesera v. Republic of Rwanda concerns a convicted génocidaire who alleged various violations of his right to a fair trial as well as his physical and mental integrity. An analysis of the African Court’s decision in Mugesera can provide additional insight on the implications of Mugesera not only for the Rusesabagina trial but also for the status of human rights and the stability of the rule of law in both Rwanda and on the African continent as a whole.

The Origins and Operations of the African Court

The African Court is the judicial arm of the African Union and was established under Article 1 of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. It entered into force on Jan. 25, 2004, after it was ratified by more than 15 countries. In December 2020, the Democratic Republic of Congo became the most recent country to ratify the protocol, bringing the total number of countries having ratified it up to 31. The court’s overall mission is to strengthen human rights protection systems in Africa.

The court’s jurisdiction extends to all cases concerning the African Charter, the protocol or any other human rights instruments ratified by the states involved. Cases may be referred by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, states parties and African intergovernmental organizations. Countries may also choose to permit individuals as well as nongovernmental organizations to directly access the court, but only six countries have currently taken this step.

Under the protocol, the court comprises 11 judges elected by the African Union from “among jurists of high moral character and of recognized practical, judicial or academic competence and experience in the field of human and peoples’ rights.” They must be nationals of countries within the African Union, and there may not be two judges from the same country at any one time. These judges serve six-year terms and may be reelected only once. Importantly, the court is permitted to formulate its own rules and procedures. Judgments are made by a majority of judges, and the majority is required to provide reasoning for its decisions. States parties then commit to comply with the judgments as stipulated by the court.

Background, Analysis and Holding of Mugesera

Léon Mugesera was convicted of incitement to commit genocide and sentenced to life in prison in April 2016, largely on the basis of a major public speech in which he called for the extermination of the Tutsis. In the book “We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families,” an important early work on the Rwandan genocide, Philip Gourevitch argued that this speech was a crucial foundation for the genocide. Mugesera has sought relief in Rwandan courts in addition to the African Court.

Mugesera claimed that Rwanda violated his rights to a fair trial, specifically his rights to defense and legal assistance as well as his right to be heard by an independent and impartial court. Additionally, Mugesera alleged that Rwanda had subjected him to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; violated his physical and mental integrity; and violated his right to family and information. Mugesera urged the African Court to order his release, appoint a doctor to evaluate his health, instruct Rwanda to establish an impartial procedure to ensure the protection of his human rights, grant reparations and institute other appropriate remedial measures.

Rwanda refused to participate in the proceedings in any capacity. In a letter dated March 1, 2016, it withdrew from the declaration that allows individuals to file cases directly with the African Court on the basis that such power was being abused by genocide convicts and fugitives, according to Minister of Justice Johnston Busingye. In Ingabire Victoire Umuhoza v. Republic of Rwanda, the African Court ruled that such withdrawal would be effective only after a notice period of one year. Because Mugesera submitted his case on Feb. 28, 2017, before the withdrawal was effective, the court ruled that personal jurisdiction was established. The court also concluded that it had material, temporal, and territorial jurisdiction, respectively, on the basis that the violations alleged by Mugesera were related to the African Charter, ongoing and committed by and on the territory of Rwanda, a party to the protocol.

The court then turned to the question of admissibility, focusing particularly on whether Mugesera had exhausted domestic remedies—as required by both the African Charter and the rules of the court. Because Mugesera alleged that the Supreme Court had rendered a decision on his case that was not subject to further appeal and Rwanda submitted no evidence to the contrary, the court found the case to be admissible.

Turning to the merits, the court first addressed the allegation that Rwanda had violated Mugesera’s right to defense by refusing to hear his arguments and witnesses, trying him in Kinyarwanda, a language he did not speak, and failing to provide him with the information necessary for the preparation of his defense. Noting that one of the members of his legal team was a Rwandan national, the court dismissed the language claim. Although the court was more sympathetic to the remaining claims, and even appeared at one point in its opinion to conclude that Rwanda had violated the right to defense, the court confusingly—and with little analysis—ultimately held that this right had not been violated.

The court then addressed the allegation that Rwanda had violated Mugesera’s right to legal assistance. The court noted that while Mugesera claimed to be indigent, he was represented by a lawyer from Rwanda as well as two foreign lawyers, suggesting that Mugesera did not lack the resources to obtain a lawyer of his choice. Mugesera also argued that because his lawyer had been fined and subsequently not permitted to appear in court, Rwanda had violated his right to legal assistance. The court rejected this claim, however, on the ground that Rwanda was permitted to impose sanctions on lawyers who violate professional or ethical obligations, such as unreasonably delaying the trial (as in this instance), and that doing so was not clearly linked to the right of legal assistance. The court also rejected Mugesera’s allegation that Rwanda had violated his right to be heard by an independent and impartial court. Although the court acknowledged that Human Rights Watch and various other organizations had raised concerns regarding the independence and impartiality of Rwandan courts, it argued that these general allegations were insufficient to support his claim.

The court was more receptive to Mugesera’s assertions that Rwanda had subjected him to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; violated his right to physical and mental integrity; and violated his right to family. Related to cruel and inhuman treatment, the court first determined that there was sufficient evidence that Mugesera had received numerous death threats from Rwandan police officers and prison officials, and then argued that such death threats were incompatible with the right to dignity. Combined with the fact that Mugesera had been deprived of adequate food as well as an orthopedic pillow (which produced poor sleeping conditions) and granted only limited access to a doctor and medication, the court determined that Rwanda had subjected Mugesera to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. The court relied on these same established facts to conclude that Rwanda had disrespected Mugesera’s physical and mental integrity. Finally, the court recognized that Mugesera was repeatedly denied access to a telephone to speak with his family and that even when he was able to receive calls, they were limited to 10 minutes. Although the court conceded that the exercise of the right to family is inherently restricted if a family member is being detained, it concluded that Mugesera had not been given the reasonable ability to receive communication from his family and that this right had therefore been violated as well.

For relief, the court compensated Mugesera on the basis of “moral prejudice” suffered by him and his family as well as reimbursement for the fees paid to his lawyers. It also ordered Rwanda to appoint an independent medical doctor to assess his health. Finally, the court ordered Rwanda to report the measures it took to implement the judgment within six months with additional reports thereafter until compliance with the ruling was achieved.

Possible Insight and Implications of Mugesera

In the most basic sense, the court’s discussion in Mugesera demonstrates that Rwanda is clearly willing to violate the fundamental human rights of those it believes to be guilty of serious crimes. Although it remains to be seen whether Rwanda will engage in identical actions in Rusesabagina’s case, which has attracted significant international scrutiny, its willingness and ability to do so in Mugesera strongly suggests that it will. The fact pattern in Rusesabagina’s case is already matching that of Mugesera. Rusesabagina has reportedly been denied lawyers of his choice, specifically international lawyers, and he has also been unable to make confidential calls to his lawyers. In broadcast excerpts released by Al Jazeera, Minister Busingye even admits to intercepting privileged communications between Rusesabagina and his lawyers. Rusesabagina’s family has further claimed that Rwandan authorities have withheld access to thousands of pages of documents in his case file. Most recently, the court rejected his request to delay the trial by six months to permit him to prepare his defense.

The court’s analysis in Mugesera indirectly outlined and foreshadowed Rusesabagina’s current experience. Indeed, the details of Mugesera’s previous trial are particularly valuable in the midst of a pandemic, when information coming from within Rwanda is more limited. Mugesera’s experience may yield additional insight as to how Rusesabagina’s trial and detainment will continue to play out.

As prominent as the Rusesabagina trial currently is, however, there is an alarming and likely more impactful aspect of the Mugesera decision. As discussed previously, Rwanda deliberately elected not to participate in the proceedings, and much suggests that it will not adhere to the orders of the court in Mugesera. Although a lack of cooperation with the African Court is not a new development, the brazen disregard that Rwanda is displaying toward the court’s decisions suggests that such regional human rights bodies on the continent will face increasing challenges in the years ahead. It is notable that since 2016, three additional countries—Tanzania in 2019 and Côte d’Ivoire and Benin in 2020—have followed Rwanda’s lead. In Benin’s case, the country specifically cited the earlier withdrawal of Rwanda as justification for its decision. To the extent that Mugesera foreshadows the continued weakening of mechanisms designed to promote justice and accountability for severe human rights violations in Africa, there are potentially steep consequences for security and stability throughout the continent.

.jpg?sfvrsn=31790602_7)