Remembering the Montgomery Ward Seizure: FDR and War Production Powers

On its anniversary, the Montgomery Ward episode is a stark reminder of what unleashing wartime government power over industry has actually looked like.

Every student of national security law knows about Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (the Steel Seizure Case), in which the Supreme Court invalidated President Truman’s seizure of steel mills to forestall a nationwide strike during the Korean War. Less well appreciated is that industrial confiscation was a familiar practice for Americans in 1952. Although the Roosevelt administration disfavored that policy tool, the U.S. government seized companies during labor disputes more than four dozen times during World War II—usually firms producing war materials. No seizure generated as much controversy as those involving Montgomery Ward & Company.

On this date in 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered his secretary of commerce to seize Montgomery Ward’s Chicago-based corporate headquarters. Two days later, soldiers carried the company’s scowling CEO from the building, sparking political outcry.

The affair is little remembered today, probably because it resulted in no judicial precedent. But its story illuminates the enormous breadth of Roosevelt’s asserted wartime emergency powers and the recent executive branch practice that the Truman administration unsuccessfully invoked.

Montgomery Ward and Seizure Statutes in World War II

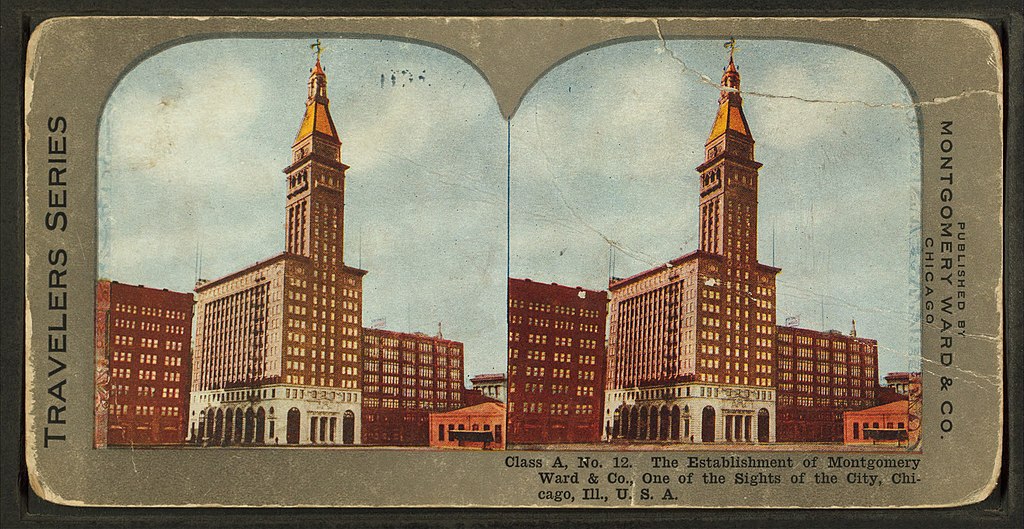

Montgomery Ward once was a behemoth of American business. During the opening decades of the 20th century, it was second only to Sears, Roebuck and Company in net mail-order retail sales. Its domineering chairman and CEO, Sewell L. Avery, detested organized labor and regularly resisted employee unionization. (Workers found it appropriate that deleting the periods after Avery’s initials made his name spell “slavery.”) Arch-capitalist Avery also reviled Roosevelt and the New Deal.

By 1943, Montgomery Ward served 30 million customers not only through mail-order deliveries but also via 600 stores and 78,000 employees in 47 states. Two-fifths of U.S. mail-order business went through Montgomery Ward, as did one-fifth of all manufactured products purchased by American farmers. Notably, the company repeatedly promoted itself as essential to the war effort. It sought and received from the War Production Board tens of thousands of “priority” and “preference” ratings, which gave it special access to scarce resources.

The Two Seizures

The first signs of trouble came in 1942, when Avery insisted that he would not accede to a deal with the union representing workers at Montgomery Ward’s central Chicago warehouse (devised by the National War Labor Board, or NWLB, a federal agency for mediating labor disputes) unless personally ordered to comply by the president. When Roosevelt did so, Avery yielded, albeit under protest. One year later, however, labor negotiations faltered again. This time, Avery refused to renew the contract, obey NWLB orders or recognize the Chicago warehouse union.

Under Section 7 the War Labor Disputes Act of 1943 (the Smith-Connally Act), the NWLB had jurisdiction only over disputes that might “lead to substantial interference with the war effort.” Montgomery Ward’s lawyers took the position that its primary areas of business were not related to the war effort and, as such, the NWLB lacked jurisdiction over it. Likewise, the company’s attorneys contended that Montgomery Ward was beyond the scope of Section 3 of Smith-Connally, which—upon certain fact-finding—authorized the president “to take immediate possession of ... any plant, mine, or facility equipped for the manufacture, production, or mining of any articles or materials which may be required for the war effort or which may be useful in connection therewith.”

After months of back-and-forth, the union struck on April 12, 1944. Unable to cajole both sides to reconcile, Roosevelt had no good options. On April 25, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9438, which authorized and directed the secretary of commerce to seize Montgomery Ward’s Chicago-based plants and facilities and operate them “in any manner that he deems necessary for the successful prosecution of the war[.]” In so doing, Roosevelt justified his actions “by virtue of the power and authority vested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States, as President of the United States and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States[.]”

Roosevelt surely relied on an opinion by Attorney General Francis Biddle dated three days earlier outlining the legal authorities for seizing Montgomery Ward. Biddle began by describing the company’s centrality to the wartime economy. Not only did one of its divisions produce military aircraft components, but more generally, Montgomery Ward was “engaged in making or distributing other goods that are essential to the maintenance of the war economy.” Indeed, the nation’s entire agricultural system depended on the company’s distribution of supplies. Biddle noted that the federal government had “recognized the importance of [Montgomery Ward] to our war economy” by granting its requests for priority and preference ratings; the clear implication was that Avery could not insist that his company was essential to the war when he thought it profitable but deny it when inconvenient. Biddle also described the risk of spillover should the Chicago strike continue for any length of time, with the potential for cascading disruptions nationwide. Accordingly, Biddle—without parsing the language of the statute—concluded that Roosevelt could use Section 3 of Smith-Connally to seize Montgomery Ward.

Yet Biddle—perhaps sensing an opportunity to forge new ground for presidential power—did not confine himself to the statutory basis alone. He proceeded to express a sweeping view of executive power based on the amalgam of authorities conferred by the Executive Vesting, Commander-in-Chief and Take Care Clauses in Article II: “In time of war when the existence of the nation is at stake, this aggregate of powers includes authority to take reasonable steps to prevent nation-wide labor disturbances that threaten to interfere seriously with the conduct of the war.” He continued: “In modern war the maintenance of a healthy, orderly, and stable civilian economy is essential to sucessful [sic] military effort.” Biddle thus concluded that the statutory and constitutional bases, “considered either separately or together, authorize[d]” the seizure.

Early on April 26, Under Secretary of Commerce Wayne Chatfield Taylor accompanied a Justice Department attorney to visit Avery at Montgomery Ward’s Chicago offices. A U.S. marshal, eight deputies and almost four dozen soldiers later joined them. The use of the military to seize Montgomery Ward was a source of friction within the administration. According to Biddle’s 1962 memoir, Secretary of War Henry Stimson had pleaded unsuccessfully: “[E]very man was needed in the war effort; it is a great army, Mr. President, it must not be sent to act as clerks to sell women’s panties over the counter of a store.”

Avery refused to compromise. When Biddle met with Taylor in Avery’s office during the morning of April 27, Avery came in and would not budge from his chair. So, Biddle ordered soldiers to eject Avery from the premises. While being removed from his office, Avery declared “to hell with government” and then turned to Biddle and snarled: “You New Dealer!” An AP photographer captured the fairly ridiculous image of the nearly 70-year-old man, arms crossed and haughty as ever, being carried out of the building by a pair of soldiers. The instantly iconic photograph was soon published on the front pages of newspapers across the country. (See the famous image here).

Less than two weeks later, the government relinquished control of the company. Why so soon? To begin with, the seizure proved unpopular. A Gallup poll released on May 6 found that about 60 percent of Americans thought that it was a mistake. To most people, Avery was not the parsimonious enemy of the common worker; rather, he was the sympathetic victim of government overreach during a time of massive federal expansion and power. The House formed a select committee to conduct hearings and draft a formal report on the seizure (a special Senate judiciary subcommittee later released a scathing report of its own). Although congressional reaction was predictably mixed, some members singled out and attacked Biddle’s written opinion—publicized on the same day as the seizure—for its breathtaking view of executive authority in wartime. Speaking on the Senate floor on April 28, one Democratic senator asked rhetorically: “Does Francis Biddle cherish the ambition to be an American Himmler?” In an election year, these tremors of dissatisfaction could not easily be ignored. Meanwhile, the seizure’s efficacy was limited since Avery could still manage most corporate affairs by telephone.

Once back in control, Avery proved himself to be an unchanged man. So, when a strike broke out at Montgomery Ward’s Detroit facilities in late December 1944, the government seized the company’s operations in nine cities (including, again, the Chicago headquarters).

The Roosevelt administration also initiated high-stakes litigation seeking declaratory and injunctive relief to support its seizure. The district court ruled against the government on both statutory and constitutional grounds (effectively rebuking Biddle’s entire opinion). A divided U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit reversed. The majority ruled in favor of the government on statutory grounds, holding that the word “production” in Smith-Connally included the handling and transporting of goods in which Montgomery Ward was engaged. Without needing to reach the issue, the majority also nodded at Biddle’s constitutional argument with references to prior Supreme Court cases favoring the use of emergency powers.

The government likely would have won on statutory grounds at the Supreme Court, too, but the war’s end precluded a high court resolution. At 11:59 p.m. on Oct. 18, 1945—the day before the government filed its response in the Supreme Court—federal authorities returned Montgomery Ward’s properties. On Nov. 5, the court granted the company’s petition for a writ of certiorari, only to immediately vacate the Seventh Circuit’s judgment and remand the case with directions to dismiss the case as moot.

Montgomery Ward’s Shadow in Youngstown

Fast forward seven years to the height of the Korean War. When the Truman administration seized the nation’s steel mills amid an intractable labor dispute, it lacked the statutory basis that Roosevelt had claimed. After World War II, Congress allowed Smith-Connally to expire and replaced it with the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 (the Taft-Hartley Act). Taft-Hartley did not allow for immediate government seizure of industry; at most, the president could seek a judicial injunction of a strike for up to 80 days while an independent committee prepared a report. Accordingly, Truman had to justify the seizure by invoking his inherent presidential powers.

As the Truman administration rushed to defend its steel company seizure, the Montgomery Ward affair provided a partial road map. Indeed, the government copied almost verbatim most of the discussion of Article II presidential seizure powers from its Montgomery Ward briefs for reuse in front of the district court. Truman faced different statutory terrain than his predecessor, and this was a different type of war, but the constitutional arguments were much the same.

The Supreme Court majority in Youngstown interpreted Taft-Hartley to preclude seizure as a remedy, so we don’t know how it would have treated the constitutional argument inherited from Montgomery Ward if Congress had been silent (that is, in Justice Robert Jackson’s typology, a Category 2 case). However, two justices expressed very different takes on the Montgomery Ward affair and Biddle’s opinion.

In a footnote to his concurrence against the Truman administration, Justice Felix Frankfurter characterized Biddle’s opinion as “rest[ing] the power to seize Montgomery Ward on the statutory authority of the War Labor Disputes Act,” and he noted that the Seventh Circuit had upheld the seizure on that basis alone. That’s technically true, but it breezes past Biddle’s alternative, boldly expansive constitutional argument and the Seventh Circuit’s approving nod in dicta.

By contrast, Chief Justice Fred Vinson—writing for three dissenters—quoted favorably from the Biddle opinion and noted acidly that Biddle’s immediate predecessor and successor—both of whom were now members of the Youngstown majority—had expressed similar views on presidential power while serving as attorneys general. (During the Montgomery Ward affair, Vinson had served as director of the wartime Office of Economic Stabilization and had advised Biddle on the seizures.) Vinson also quoted from the House select committee majority report as supporting inherent presidential power for seizures even in the absence of statutory authorization, before noting that the Seventh Circuit also seemed to support this view. In doing so, however, Vinson read too much into the House report, which actually punted on that constitutional issue.

A decade after Youngstown, Biddle reflected on the case and compared it to the Montgomery Ward episode. He continued to defend his constitutional argument and was skeptical that the court in Youngstown had discredited it; downplaying the Korean conflict situation, he distinguished the steel emergency as “born of the cooler issues of peace” rather than, as he had faced in 1944, “the persuasive heat of war.” After praising Vinson, “who from his experiences as a war administrator knew the necessity of concentrating in the hands of the Commander in Chief all power reasonably calculated to carry on war,” he ominously concluded: “To what extent [Youngstown] will control or curb the actions of Presidents in future wars remains to be seen—if there is a survivor to review his action.”

* * *

Today, President Trump calls himself a “wartime president” in combating COVID-19. He claims to have “unleash[ed] the full power of the federal government,” but he has dithered even in using statutory authorities to control industrial production of critical medical supplies.

The Montgomery Ward episode is a stark reminder of what unleashing wartime government power over industry—including assertions of immense Article II powers—has actually looked like.

Authors' note: Those interested in reading more about this episode, including how it fits in the context of other WWII seizures, should read Chapter 5 of Mark Wilson's Destructive Creation. That chapter also includes references to other detailed histories of these events.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5a43131e_9)