The South China Sea Dispute: A Brief History

A small outcropping of sand occasionally breaks the vast expanse of the South China Sea. These islands are modest, even diminutive, but they form the core of a fierce territorial dispute among six primary claimants: Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. These claimants also clash over their rights and duties in the nearby waters as well as the seabed underneath.

A small outcropping of sand occasionally breaks the vast expanse of the South China Sea. These islands are modest, even diminutive, but they form the core of a fierce territorial dispute among six primary claimants: Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. These claimants also clash over their rights and duties in the nearby waters as well as the seabed underneath.

The disputes in the South China Sea have the potential to ignite a broader regional conflagration. Multiple claimants contend over issues of sovereignty not susceptible to easy legal resolution. Worse, the stakes are high: the Sea is one of the primary routes for international trade, and many claimants believe that the Sea hides bountiful oil reserves in addition to its plentiful fishing stocks. The disputes are further entrenched by rampant nationalism, as each claimant attaches symbolic value to the South China Sea islands that far exceeds their objective material wealth. And, finally, the disputes are also tinged by great power politics as China and the United States begin to jostle each other for control of the international order.

Over the last year, disputes in the South China Sea have dominated headlines, and they seem sure to continue to generate fresh national security issues. Already, too, they have raised a variety of legal questions that will inform the future course of both the conflict and the region.

Accordingly, Lawfare decided to prepare a backgrounder on the South China Sea that proceeds in two parts. First, in this part, I will lay out the history of the disputes and highlight key events necessary to understanding the crises of the day. In the second part (which will run later this week), I will introduce the primary legal issues underlying the disputes.

Centuries of Contested History

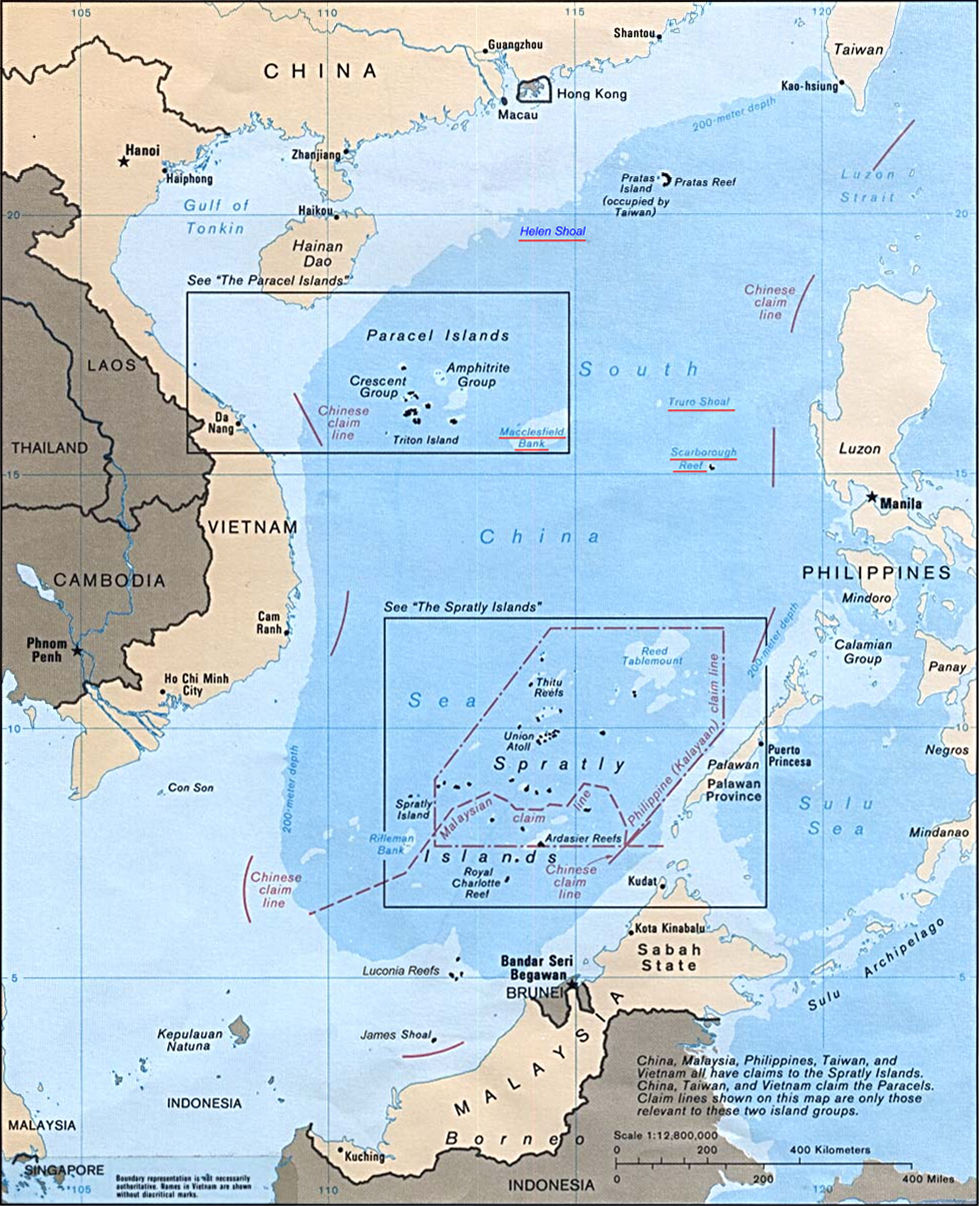

As readers can see in the map above, the islands of the South China Sea can largely be grouped into two island chains. The Paracel Islands are clustered in the northwest corner of the Sea, and the Spratly Islands in the southeast corner.

Reflecting the Rashomon nature of the dispute, the claimants have argued bitterly over the “true” history of these island chains. Some have tried to ground their modern claims by proving a long and unbroken record of national control over claimed features. These states assert that, for example, their nationals fished around the islands of the Sea or used them for shelter from storms. In particular, Beijing has taken an active role in subsidizing archeological digs to find evidence of exclusive Chinese usage of the Sea’s many features since time immemorial.

It is hard—if not impossible—to wade through these partisan claims (many of which constitute pure propaganda). No impartial tribunal has yet taken on that challenge. To the extent that it is possible to draw any conclusions from the morass, though, it seems fair to say that no claimant has conclusively demonstrated a pattern of exclusive historical control over the South China Sea, or even over isolated parts of it.

A Period of Relative Quiet

In any case, the issue was moot for most of the region’s history. Through the first half of the twentieth century, the Sea remained quiet as neighboring states focused their attention on conflicts unfolding elsewhere.

In fact, at the end of World War II, no claimant occupied a single island in the entire South China Sea. Then, in 1946, China established itself on a few features in the Spratlys, and in early 1947, it also snapped up Woody Island, part of the Paracel Islands chain, only two weeks before the French and Vietnamese intended to make landfall. Denied their first pick, the French and Vietnamese settled for the nearby Pattle Island.

But even at this stage, the South China Sea was not seen as a priority by any of the claimants. For that reason, after suffering their cataclysmic defeat at the hands of Mao’s Communists, Chiang Kai-shek’s forces retreated to Taiwan and abandoned their stations in the South China Sea. Even the French and Vietnamese could not be bothered to take advantage of the lapse in Chinese control, as they were preoccupied with the rapidly escalating war in Vietnam.

The Claimants Rush for Control

However, the next half century saw accelerating interest in the South China Sea. In 1955 and 1956, China and Taiwan established permanent presences on several key islands, while a Philippine citizen—Thomas Cloma—claimed much of the Spratly Island chain as his own.

Once again, this phase of frenetic island occupation was cooled off by a longer period of inertia. But by the early 1970s, the claimants were at it once again. This time, though, the scramble was spurred by indications that oil lurked beneath the waters of the South China Sea. The Philippines was the first to move. China followed shortly thereafter with a carefully coordinated seaborne invasion of several islands. In the Battle of the Paracel Islands, it wrested several features out from under South Vietnam’s control, killing several dozen Vietnamese and sinking a corvette in the process. In response, both South and North Vietnam reinforced their remaining garrisons and seized several other unoccupied features.

Another decade of relative inaction was punctuated once again with violence in 1988, when Beijing moved into the Spratlys and set off another round of occupations by the claimants. Tensions crested when Beijing forcibly occupied Johnson Reef, killing several dozen Vietnamese sailors in the process.

Once again, though, tensions deescalated for a few years, only to rise again in 1995, when Beijing built bunkers above Mischief Reef in the wake of a Philippine oil concession.

Diplomatic Developments

The dispute seemed to take a turn for the better in 2002, when ASEAN and China came together to sign the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. The Declaration sought to establish a framework for the eventual negotiation of a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea. The parties promised “to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.”

For a while, the Declaration seemed to keep conflict at bay. Over the next half decade, Beijing launched a charm offensive across Southeast Asia, and the claimants refrained from provoking each other by occupying additional features.

Rather than fighting battles out on the Sea, though, the claimants began to needle each other through demarches and notes verbales. In May 2009, Malaysia and Vietnam sent a joint submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf setting out some of their claims. This initial submission unleashed a flurry of notes verbales from the other claimants, who objected to the two nation’s claims.

In particular, China responded to the joint submission by submitting a map containing the infamous “nine-dash” line. This line snakes around the edges of the South China Sea and encompasses all of the Sea’s territorial features as well as the vast majority of its waters. However, Beijing has never officially clarified what the line is meant to signify. Instead, it has maintained “strategic ambiguity” and said only that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof (see attached map).” This could mean that China claims only the territorial features in the Sea and any “adjacent waters” allowed under maritime law. Or it could mean that China claims all the territorial features and all the waters enclosed by the nine-dash line, even those that exceed what’s permitted under maritime law.

Recent Crises

Since the publication of the nine-dash line, the region has grown increasingly concerned by China’s perceived designs on the South China Sea. In 2012, Beijing bore out some of these concerns when it snatched Scarborough Shoal away from the Philippines. The two states had quarreled over allegations of illegal poaching by Chinese fishermen. After a two-month standoff, the parties agreed to each withdraw from the Shoal. Manila did. Beijing did not. Since then, China has excluded Philippine boats from the Shoal’s waters.

In response to this escalatory move, Manila filed an arbitration case against China on January 22, 2013, under the auspices of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Philippine claims center around maritime law issues, although China asserts that they cannot be resolved without deciding territorial issues first. For that reason, Beijing has largely refused to participate in the proceedings, although it has drafted and publicly released a position paper opposing the tribunal’s jurisdiction. The Philippines has submitted its memorial as well as a response to China’s position paper, and both nations are currently awaiting a decision from the tribunal as to its own jurisdiction.

As the case proceeds in the background, China has adopted an increasingly assertive posture in the region. In early May 2014, a Chinese state-owned oil company moved one of its rigs into waters claimed by Vietnam south of the Paracel Islands. This provocation touched off confrontations between Vietnamese and Chinese vessels around the rig, as well as rioting against foreign-owned businesses in parts of Vietnam. Faced with this pushback, China withdrew the rig in mid-July, a month ahead of schedule.

Additionally, over the last year, Beijing has launched an accelerating land reclamation campaign across the South China Sea. In at least seven locations, Chinese vessels have poured tons of sand to expand the size of features occupied by China. Beijing has also begun construction of infrastructure on much of this reclaimed land, including an airstrip capable of receiving military aircraft. Although other claimants have reclaimed land in the past, China has reclaimed 2,000 acres of new land, more than “all other claimants combined over the history of their claims,” according to the U.S. Department of Defense.

The other claimants have condemned this latest project as counterproductive, and President Obama has urged China to stop “throwing elbows and pushing people out of the way” in pursuit of its interests. Thus far, Beijing has not complied with these entreaties, and it is unclear what the next twist or turn in the story of the South China Sea will be.