Spyware Vendors Target Human Rights + Ukraine Adopts Defend Forward Strategy

The latest edition of the Seriously Risky Business cybersecurity newsletter, now on Lawfare.

Editor’s Note: This newsletter is part of a collaboration between Lawfare and Risky Business. You can find the full version of the Seriously Risky Business newsletter and previous editions on news.risky.biz.

The Spyware Ecosystem That Targets Human Rights

A new report turns a harsh spotlight onto the commercial surveillance industry that markets spyware reportedly used by bad actors to target human rights defenders, dissidents, and other “high risk” users.

Published by Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG), the report and accompanying blog describe what TAG calls a “lucrative industry” that sells governments and “nefarious actors” the ability to exploit vulnerabilities in consumer devices.

The report states that while spyware vendors point to their tools’ “legitimate use in law enforcement and counterterrorism,” analysis from Google and researchers from the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab and Amnesty International uncovers the use of spyware against “high risk users” such as journalists, human rights defenders, dissidents, and opposition party politicians.

TAG separates players in the commercial surveillance industry into four primary categories:(a) vulnerability researchers and exploit developers, (b) exploit brokers and suppliers, (c) what Google calls commercial surveillance vendors (CSVs), and (d) government customers.

The report’s authors describe CSVs as:

private technology companies based all over the world. Rather than operating secretly like ransomware and extortion groups, many operate openly. Like any other software product company, they have websites and marketing materials, sales and engineering teams, job openings listed on their websites, publish press releases, and even attend conferences.

The number of CSVs around the globe is impossible to count, with new companies opening each year and existing ones reincorporating under new names. TAG currently tracks approximately 40 CSVs developing and selling exploits and spyware to government customers.

TAG then provides thumbnail sketches of five of these companies: Cy4Gate and RCS Lab, a company owned by Cy4Gate; Intellexa Alliance; Negg Group; NSO Group; and Variston. These sketches summarize public reports and information that describes how these companies’ products have been used across the world.

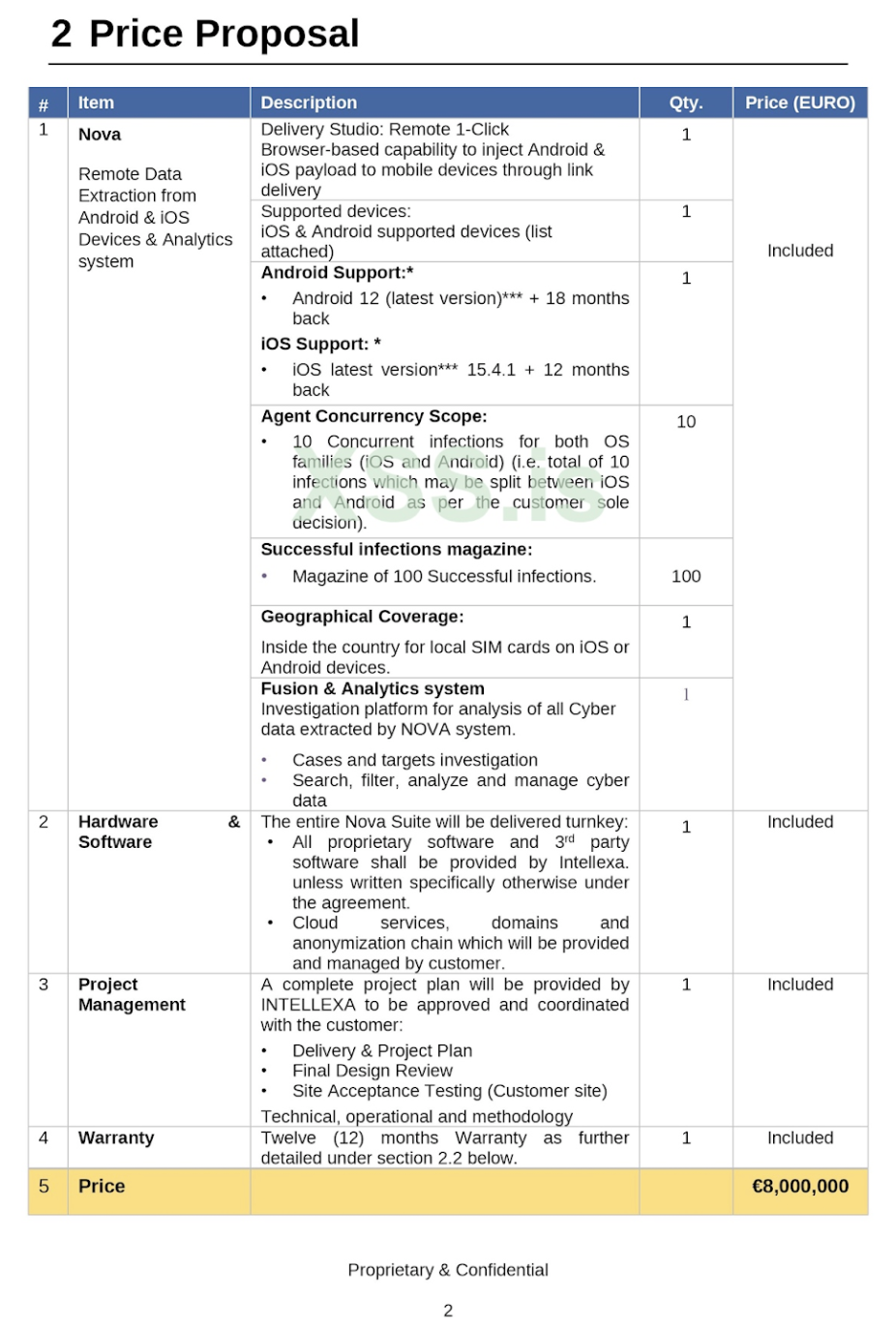

The TAG report also cites an example of how some CSV services are marketed to potential clients, based on a 2021 pitch document for the Intellexa Alliance’s Nova system, reported by the New York Times:

For €8 million the customer receives the capability to use a remote 1-click exploit chain to install spyware implants on Android and iOS devices, with the ability to run 10 concurrent spyware implants at any one time. In this example, while the spyware can only run on 10 different devices concurrently, it can be switched between devices or re-infect the same device for up to 100 infections.

A number of optional features were available at extra cost, according to the pitch document. For example, a base offering limited infections to local SIMs, but targeting phones in another five countries was available for an extra 1.2 million euros. Having implants persist when victims rebooted their phones was available for an additional 3 million euros.

Part of an Intellexa “Nova” pricing proposal, Source: Amnesty International Security Lab

The most impactful part of the TAG report examines the experiences of three people—a human rights advocate and two journalists—who, the report says, were targeted with Pegasus, spyware developed by NSO Group.

These stories are worth reading. Separately, Pegasus has reportedly been linked to harms to civil society all over the world. (NSO Group has pushed back against this reporting.)

More narrowly, the industry plays a significant role in cybersecurity. Google’s report says CSVs are behind nearly half the zero day exploits it has identified from mid-2014 through 2023.

The report also provides a small illustration of the cut and thrust that takes place between CSVs and Google’s product patching:

On April 14, 2023, Chrome released patches for CVE-2023-2033 and CVE-2023-2136, which Intellexa were using in a 0day exploit chain to install their spyware. Following the Chrome security update, TAG saw a dip in activity by Intellexa’s customers for over 40 days, followed by a spike in activity at the end of May when Intellexa released a new 0day exploit for the next version of Chrome. It took Intellexa roughly 45 days to develop and deploy a new 0day exploit for Chrome 113. TAG quickly discovered the new exploit and Chrome released a fix for the new 0day within four days. Intellexa’s customers were only able to use the new exploit for less than a week, as Chrome patched the bug, tracked as CVE-2023-3079, in an update released on June 5.

The report points out that these groups “pivot and persist” despite legal action and public reporting.

NSO Group continues to operate and is lobbying to be removed from a U.S. blacklist. Other companies have changed names multiple times.

So, what to do about commercial spyware then?

Last week, a group of international governments and stakeholders launched the Pall Mall Process, “an ongoing globally inclusive dialogue to address the proliferation and irresponsible use of commercial cyber intrusion tools and services.”

Interestingly, in its declaration, the Pall Mall Process recognizes that “many of these tools and services can be used for legitimate purposes.” That’s right, but it’s something that Google’s report gives short shrift to.

Rather than crushing the industry, the declaration focuses on four “pillars”: accountability, precision, oversight, and transparency. Those are the kinds of things you focus on when tools are dual-use and can be used for good or ill.

A pretty good collection of governments and regional bodies signed up, including, interestingly, both Greece and Poland. These two countries have been accused of abusing commercial spyware for political advantage.

Unfortunately, the declaration announcing the Pall Mall Process made absolutely no commitment to actually do anything, either. Despite that, we are hopeful because there are governments that are genuinely dedicated to tackling the problem.

Ukraine Adopts U.S. “Defend Forward” Strategy

A Ukrainian government official has declared that the country’s cyber forces have gone on the offensive.

At a conference held in Kyiv, Illia Vitiuk, the head of cybersecurity at Ukraine’s security service (the SBU), said that the country had to “act proactively,” according to The Record. Vitiuk likened this offensive strategy to U.S. Cyber Command’s defend forward strategy, which aims to “disrupt malicious cyber activity at its source.”

The first indication of this change in strategy came in October 2023, when an anonymous security service source linked the hack of a Russian bank with the SBU. Since then, the GUR, Ukraine’s military intelligence agency:

Announced in mid-December that Ukrainian defense intelligence cyber units “completely eliminated” Russia’s federal tax service and disrupted the company that serviced its information technology (IT).

Claimed responsibility in late January for destroying “the entire IT infrastructure” of IPL Consulting, a company that provides IT services to the Russian defense-industrial complex.

Said in early February that it had disrupted the system Russian forces use to reprogram DJI drones for military operations.

These operations make sense because they aimed for outcomes that could not be achieved with conventional military force. It is also pretty straightforward to see how disruption in these cases could have significant—but not decisive—impacts on Russian military effectiveness.

However, it is not clear that these operations have, in fact, been effective. The Russian tax office denied that its systems had been disrupted, and there haven’t been widespread reports of tax collection problems, for example.

The SBU and the GUR have also publicized the actions of purported Ukrainian hacktivist groups and said that, for some incidents, they’ve been “involved” or even assisted the operations:

The GUR published documents in November 2023 from the hack of Rosaviatsiya, Russia’s civil aviation authority.

The SBU said in early January that it helped a Ukrainian hacktivist group known as Blackjack in its efforts to breach Russian ISP M9com in response to the destructive Kyivstar attack.

The GUR said in early January that it received about 100 gigabytes of data from the hack of Russia’s Special Technology Center (STC), maker of Russian military equipment including the Orlan unmanned aerial vehicle.

The GUR announced in mid-January Blackjack’s breach of a Russian Ministry of Defense-linked construction enterprise and its theft (and subsequent deletion from Russian servers) of 1.2 terabytes of data relating to Russian military facilities.

The GUR announced in late January a destructive attack by the “BO Team” hacker group against Russia’s State Research Center on Space Hydrometeorology.

Without singling out particular incidents, Vitiuk says intelligence gained by Ukraine’s more proactive cyber efforts had helped ground operations, including attacks on Russian military infrastructure.

The intelligence Ukraine has gathered has also helped prevent cyberattacks. Vitiuk said that about a year ago another telecommunications operator had been the intended target of a Kyivstar-style destructive attack, but the attack was prevented when Ukrainian hackers learned of the operation in advance.

Cyber operations are often kept secret, but in this case the Ukrainian government is actively publicizing them.

One factor here is that once destructive operations are carried out, there is no need for secrecy. If they have been effective, the Russians will already know about them. And Ukraine needs international support, so successful operations are a demonstration that the country is still fighting the good fight.

This shift in strategy by the Ukrainian government illustrates the usefulness of cyber operations in the context of a large-scale conventional war.

Why Banning Ransomware Payments Makes No Sense

Ransomware incident response firm Coveware’s latest quarterly report comes out strongly against banning ransomware payments. This is a must-read for policymakers mulling the pros and cons of a ban.

Coveware assembles an array of arguments against banning payments, including that a ban would not reduce ransomware, but would instead place badly affected firms in an even worse position where they either break the law or potentially fail.

It would also, overnight, create a market of “data recovery companies” that are actually ransomware operators masquerading as legitimate firms.

A ban would also discourage victims from reporting incidents, which would undercut the progress authorities have made fighting ransomware. Coveware instead argues for mandatory reporting of ransomware incidents.

Three Reasons to Be Cheerful This Week:

Secret Rhysida decryptor: For nine months, incident response firm Emsisoft had the ability to recover files encrypted with Rhysida ransomware without a key, taking advantage of a vulnerability in the malware’s random number generator. Unfortunately, South Korean researchers have just published information about the vulnerability, meaning that Rhysida will likely fix its malware. Risky Business News has a good examination of this incident.

Dollars for Rust: Google is providing $1 million to the Rust Foundation to support efforts to improve the ability of Rust code to integrate with legacy C++ codebases. Rust is less vulnerable to memory safety security issues, so this will hopefully avoid security issues in the longer term.

New York City airport taxi dispatch hackers sentenced: Two Queens residents, Daniel Abayev and Peter Leyman, were sentenced, respectively, to four and two years in prison for hacking John F. Kennedy International Airport’s taxi dispatch system. The pair charged taxi drivers $10 to skip the taxi holding queue at JFK that frequently required hours-long waits. The pair collaborated with two Russian hackers who are still at large.

Shorts

For China, Evidence Is Optional

Cybersecurity firm Sentinel One has published a report examining the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) media strategy over the past couple of years to push narratives of irresponsible U.S. hacking.

Chinese allegations of U.S. hacking started in 2021 and were weakly bolstered by technical details that were gathered from leaked intelligence documents. Since mid-2023, however, these allegations have been aired only in state media and are entirely evidence free.

This shift away from providing any evidence goes to show that for the PRC’s purposes, proof is just unnecessary.

The Unintended Consequences of Cyber Regulation

In a parliamentary submission, the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) says it has observed a “decline in the quantity and quality of cyber security reporting to the ASD.”

The ASD says it has observed “a decrease in the frequency and richness of cyber incident reporting from the private sector, particularly critical infrastructure operators.”

Ironically, it thinks this stems in part from increasing regulation. It says that critical infrastructure operators in particular have become more “compliance-based” and look to regulatory rules to assess their reporting requirements.

From the GRU to Cyber Crime Attorney

Krebs on Security has an entertaining examination of an account on the Russian Mazafaka cybercrime forum using the handle “Djamix,” who claimed to be a licensed attorney and offered his legal services to forum members. Krebs links Djamix to an individual called Aleksei Safronov, whose Facebook profile shows him wearing a Spetsnaz GRU (special forces) uniform.

More on Volt Typhoon

Industrial cybersecurity firm Dragos has released its own report on Volt Typhoon, which it calls Voltzite. This group is worrying because it appears to be targeting U.S. critical infrastructure for disruption, and absolutely nothing in this report is reassuring. CyberScoop reported that Dragos founder Robert Lee told a media briefing that Volt Typhoon is “hitting the specific electric and satellite communication providers that would be important for disrupting major portions of the U.S. electric infrastructure.”

Risky Biz Talks

In the latest “Between Two Nerds” discussion, Tom Uren and The Grugq look at why authoritarian regimes seem to love the “cyber magic wand.”

From Risky Biz News:

Ransomware passed $1 billion mark in 2023: Ransomware gangs made out like bandits last year, collecting an estimated $1.1 billion worth of cryptocurrency via ransomware payments, according to blockchain tracking company Chainalysis.

[We covered this briefly last week, but Catalin has more, including about the number of ransoms of more than $1 million and how big game hunting is now the dominant strategy for ransomware operations.]

Authorities take down Warzone RAT gang: An international law enforcement operation has led to the capture of two individuals believed to have created and operated Warzone RAT, a Malware-as-a-Service operation that has been running since at least 2019.

Authorities have detained Daniel Meli, a 27-year-old from Malta, and Prince Onyeoziri Odinakachi, a 33-year-old from Nigeria. Meli allegedly created and sold the Warzone RAT through its official website at warzone.ws. Odinakachi allegedly worked as a customer support, providing help to the malware’s buyers. Officials say Meli has been allegedly involved in the malware underground since at least 2012 and also created and sold Pegasus RAT, a precursor of the Warzone RAT.

[more on Risky Business News]

Surveillance in Tibet: Chinese authorities are forcing Tibet residents to install an app named National Anti-Fraud Centre on their smartphones. The app has the ability to access call and SMS logs, read browser histories, and see what other apps are installed on a device. Pro-Tibet privacy groups say that the app could be used as a surveillance system to spy on China’s Tibetan population. A similar system with government-mandated mobile apps is also used to track the Uyghur minority in China’s Xinjiang province. [additional coverage in Turquoise Roof and Tibet Watch’s joint reports]

.jpg?sfvrsn=92f1ad84_5)