The Legal Profession Reckons With Jan. 6

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

At one point during the Watergate scandal, White House Counsel John Dean put together a list of people whom he thought might face criminal prosecution as a result of the unfolding investigations. Looking over the document, he noticed that a number of the names shared something in common: Many of them were attorneys. Later, testifying before the Senate Watergate Committee, Dean recalled his astonishment at the realization: “How in God’s name could so many lawyers get involved in something like this?”

The same question might be asked of the indictment brought by Special Counsel Jack Smith charging Donald Trump over his role in working to overturn the 2020 election—and, following on its heels, the indictment in Fulton County, Georgia. Of the six unnamed co-conspirators described in the special counsel’s indictment, all five who have been definitively identified are lawyers—and the sixth may be as well. What’s more, of the whopping 19 defendants charged by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, eight are attorneys—and at least two of the unindicted co-conspirators listed in the Fulton County indictment may be lawyers as well. (There’s significant overlap between the co-conspirators identified by Smith and the defendants charged by Willis.) As with Dean’s Watergate-era list, this does not make for a particularly flattering portrait of the legal profession.

Legal disciplinary authorities, apparently, agree. Four of the five identified co-conspirators in the federal indictment are currently facing ethics charges brought by state bars—proceedings separate from the criminal process, but that could end with the attorneys in question censured, suspended from the legal profession, or disbarred. Another defendant charged in the Georgia case has already been censured by the Colorado bar. And the ongoing ethics trials are beginning to face scheduling difficulties because of parallel criminal proceedings and investigations—a pileup of efforts to seek accountability for Trump’s would-be coup.

The alleged conspiracies and acts of racketeering sketched out in both indictments centrally feature alleged misconduct by lawyers. Both documents describe the co-conspirators and defendants filing lawsuits, writing legal memos, and spinning out increasingly frivolous interpretations of the Constitution and the Electoral Count Act. For law, a profession that aspires to a certain civic importance and that prides itself on being self-regulating—that is, setting its own boundaries for what does and doesn’t constitute appropriate behavior by those within the field—this has occasioned somewhat of a moral crisis.

“The Trump case shows lawyers not only failing to make sure their government clients operate within the bounds of our democratic system, but stretching to help those clients craft ways to subvert it,” Deborah Pearlstein of Cardozo Law School argued in the New York Times following the Jan. 6 indictment. Law professor Michael Dorf has suggested that the legal memos crafted by Trump boosters aiming to help the president hold onto power are akin to the “torture memos” drafted by Justice Department officials following 9/11.

As a student at Harvard Law School, Dorf writes, he happened to work alongside Kenneth Chesebro, one of the co-conspirators pointed to in Smith’s indictment and a defendant in the Georgia case as well. The extent to which the lawyers implicated by the indictments were not just members of the profession, but were embedded within elite legal institutions—John Eastman, for example, clerked for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas—is an additional twist to the story of the 2020 election and the legal profession.

Of the five co-conspirators identified from the federal indictment, Chesebro is the only one not currently facing ethics proceedings. But in 2022, two organizations—the 65 Project, whose board includes Lawfare contributing editor Paul Rosenzweig, and the group Lawyers Defending American Democracy—filed complaints against him with disciplinary authorities in New York, where he is barred. In their letters to the New York Supreme Court’s Attorney Grievance Committee, the two groups pointed to conduct by Chesebro substantially similar to that identified in both indictments: namely, his apparent role, as described by the Jan. 6 Committee, in engineering the fake electors scheme.

In contrast, bar proceedings may be furthest along in the case of co-conspirator #1—that is, Rudy Giuliani. His New York law license has been on hold since May 2021, when a New York court ruled that Giuliani’s conduct following the 2020 election “immediately threatens the public interest and warrants interim suspension from the practice of law” while bar authorities in that state continue their investigation of him. That suspension pushed Washington, D.C., courts to temporarily ban him from practicing law in the capital, as well, although his license there had not been active.

Since then, D.C.’s Office of Disciplinary Counsel has pursued ethics charges against Giuliani, focusing more narrowly on his role in litigating a Pennsylvania suit seeking to overturn the state’s counting of its votes. In July 2023, a hearing panel (made up of two lawyers and one civilian member) recommended that Giuliani be disbarred, finding that the Pennsylvania case “had no factual basis, and consequently no legitimate legal grounds” and that Giuliani’s “prosecution of the lawsuit also seriously undermined the administration of justice.” The next step is for the D.C. Board on Professional Responsibility to decide whether and how to act on that recommendation. Oral arguments before the board are currently scheduled for Nov. 2—almost exactly three years since Election Day 2020.

The filings in both the New York and D.C. proceedings against Giuliani emphasize the sense of disciplinary authorities that there’s something uniquely crucial about holding lawyers accountable for the particular efforts to steal the 2020 election. To some extent, this rests on an argument about the responsibilities of lawyers and the legal profession to democracy and the rule of law. Lies about election fraud “damage the proper functioning of a free society,” the New York court wrote in suspending Giuliani’s license—reasoning further, “When those false statements are made by an attorney, it also erodes the public’s confidence in the integrity of attorneys admitted to our bar and damages the profession’s role as a crucial source of reliable information.” Likewise, in recommending Giuliani’s disbarment, the D.C. committee declared that his “utter disregard for facts denigrates the legal profession.” And in doing so, it suggested, Giuliani damaged “public confidence in our courts” and the law as a whole.

Key to the committee’s reasoning was Giuliani’s lack of remorse. “To the contrary,” the recommendation states, “he has declared his indignation … over being subjected to the disciplinary process.” Over the course of that process, he’s pointed to the widely debunked film 2,000 Mules as evidence of potential election fraud; defended his request in the Pennsylvania case that the district court toss out the results of the state’s vote; and said that the initial Pennsylvania filings, which Giuliani characterized in court as describing how Democratic officials “stole an election,” contained “more evidence than you normally have when you bring a complaint.” After the D.C. committee recommended disbarment, a spokesman for Giuliani denounced the proceedings as “part of an effort to deny President Trump effective counsel.”

The other lawyers swept up in criminal proceedings over the 2020 election have displayed a similar defiance. In March 2023, Jenna Ellis—a member of the Trump legal team who does not appear in the federal indictment but was charged in the Georgia proceedings—initially consented to a sanction of public censure by the Colorado Supreme Court and the state’s Office of Attorney Regulatory Counsel, agreeing to a stipulation that described her repetition of election falsehoods as violating professional prohibitions on “dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.” The very next day after the court approved the censure, though, Ellis tweeted a statement claiming that she had not admitted to lying and that she would “NEVER” give in “to the political opposition mob.”

(Ellis is, arguably, splitting hairs here. Though, as she said in her tweet, she did not admit to “INTENTIONALLY making a false statement,” the stipulation states that she made multiple “misrepresentations” of fact, that she did so recklessly, and that her actions violated her duty of candor to the public. Even if her tweet is technically accurate by a narrow definition of lying, it whitewashes just how damning the stipulation’s description of her conduct is. And the instinct to defend yourself on Twitter by drawing narrow distinctions about just what you did and didn’t agree to be censured over, only a day after the censure is handed down, doesn’t exactly speak to an excess of contrition.)

Ellis’s approach may be unusually blatant. But the remaining three identified co-conspirators in the federal indictment—John Eastman, Sidney Powell, and Jeffrey Clark—have likewise appeared less than remorseful. In June, Clark complained of his “demonization” by the D.C. bar, which began proceedings against him last summer for his efforts in December 2020 to take control of the Justice Department and leverage the department’s authority to give credence to conspiracy theories about supposed election irregularities. Powell—who at various times has faced ethics charges in both Texas and Michigan, as well as court-imposed sanctions fining her and her legal team over $150,000—has continued to insist in filings before disciplinary authorities that her lawsuits baselessly claiming election fraud were legally and factually sound.

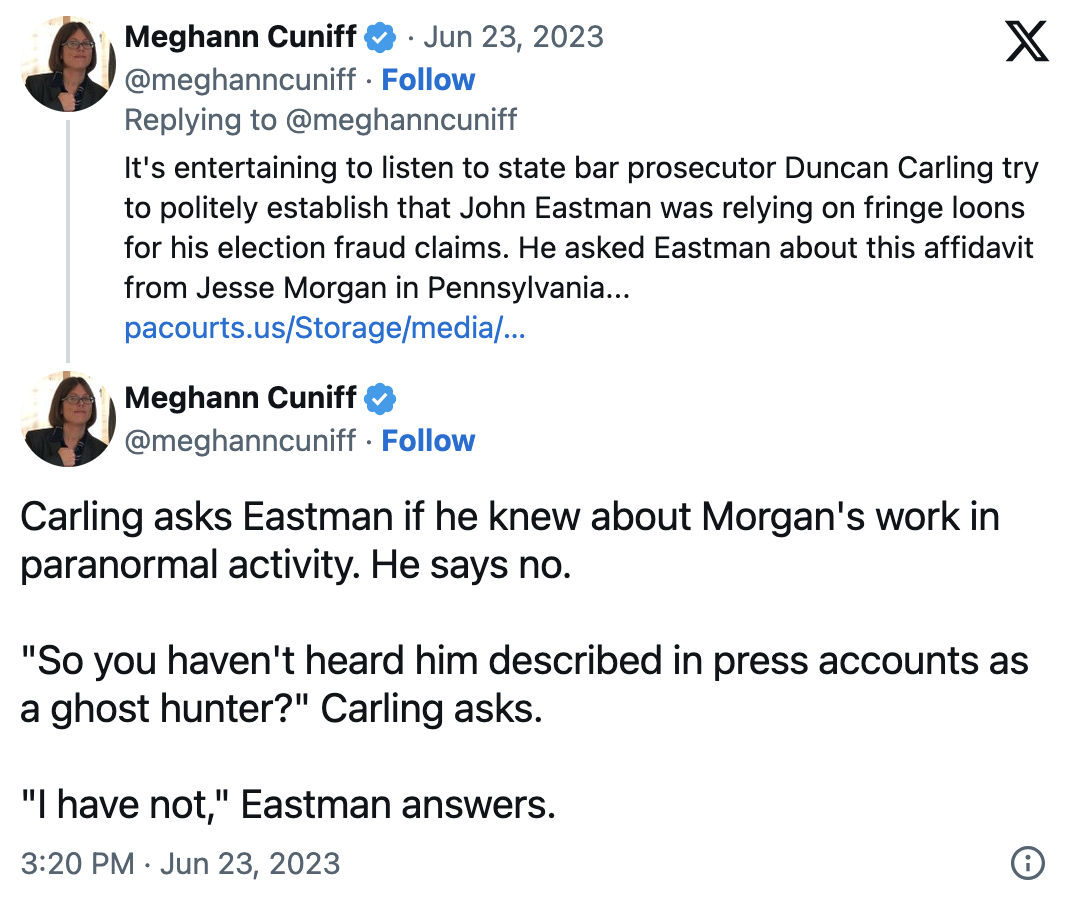

Eastman, meanwhile, hasn’t backed down either. Asked recently by a reporter whether the election was stolen after being booked at the Atlanta jail, he said that there was “no question in my mind” that it had been. California authorities have explicitly said they’re seeking his disbarment for his central role in developing the scheme for Vice President Mike Pence to upend the electoral count on Jan. 6. Eastman’s ethics trial is ongoing—and so far, during hearings, he’s held fast to his assertions of election fraud. At times, this has led to surreal exchanges, such as when counsel for the California bar questioned Eastman about the reliability of a particular source for Eastman’s claims about ballots being stolen:

https://twitter.com/meghanncuniff/status/1672323690158227457

The Eastman trial began earlier this summer and has moved forward despite Eastman’s efforts to place proceedings on hold due to the charges against him in Georgia and the potential federal case as well. Though Eastman argued that testifying in his ethics trial would place him at risk of self-incrimination in Fulton County and potentially federal court in D.C., the state bar was unimpressed, writing that Eastman’s motion for abatement was “nothing more than an opportunistic attempt” to delay his potential disbarment. (Such was the industriousness of prosecutors this August that Eastman was indicted in Fulton County in the midst of his argument with California disciplinary counsel over whether a possible federal indictment was too speculative to be worth delaying bar proceedings over.) The judge in Eastman’s discipline case agreed, ruling that Eastman had waived his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination by testifying previously during bar proceedings and that the ethics trial could continue. It wasn’t like he’d been unaware of his potential criminal exposure, she wrote—after all, he’d pleaded the Fifth “over 145 times” during his deposition a year and a half earlier before the House Jan. 6 committee.

When it comes to opportunistic attempts to delay bar proceedings, though, Jeffrey Clark has been by far the most successful. He managed to stall the D.C. bar for a full eight months by removing the case to federal court, arguing that local D.C. courts lack the authority to discipline lawyers employed by the federal government. (A federal district judge, remanding the case back to D.C. authorities, described Clark’s reasoning as “absurd.”) And while Clark and the bar were still squabbling over the removal, Clark was indicted in Georgia—prompting him to seek a stay of the D.C. proceedings along similar reasoning as Eastman’s. D.C.’s Office of Disciplinary Counsel has indicated that it opposes the delay.

If Clark’s experience is a reminder that bar discipline for the 2020 coup-plotters will potentially be a bumpy process, so too is that of Sidney Powell. She first faced ethics charges brought by the Texas bar in March 2022 over her central role in filing the “Kraken” lawsuits, the four complaints in Michigan, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Georgia alleging a vast conspiracy to swing the election to Biden. In February 2023, though, a state judge tossed out the ethics charges against her on the puzzling rationale that the Texas Commission for Lawyer Discipline had misnumbered exhibits in a filing. The conservative editorial board of the Dallas Morning News deemed the ruling a “travesty of justice.” (The bar is appealing.)

Then, in May, the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission began disciplinary proceedings against Powell and the rest of the Michigan Kraken team—an unusual move, given that Powell and several of the others lawyers facing charges are barred outside the state. That ethics case, in turn, follows on sanctions imposed by U.S. District Judge Linda Parker, who heard the Michigan Kraken litigation and described the case as “a historic and profound abuse of the judicial process.” Shortly after the Attorney Grievance Commission filed its charges, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit upheld Judge Parker’s grant of sanctions against the Kraken team, with some tweaks.

From one perspective, it’s striking just how many lawyers were involved in plans to overturn the election; recall John Dean’s list. From another, though, it’s also notable how self-contained this legal universe was and is. Repeat players pop up again and again. Take the Michigan ethics charges: After the Sixth Circuit dismissed sanctions against two lawyers on the grounds that they weren’t sufficiently involved in the Kraken litigation to face fines, the state bar dropped charges against them as well. But just a few days later, one of those lawyers, Stefanie Junttila, was indicted by a Michigan state special counsel for her alleged role breaching voting machines in an effort to prove voter fraud. Or to take another example, Jeffrey Clark’s counsel in both the Georgia prosecution and the D.C. ethics case is none other than Harry MacDougald—who signed on the Georgia Kraken complaint along with Powell. (The 65 Project has filed an ethics complaint against MacDougald for his role in both the Kraken litigation and another case that sought to enjoin the certification of Georgia election results.)

Perhaps, then, the malady that manifested itself in the form of efforts to overturn the 2020 election isn’t a widespread plague across the entire legal profession. Instead, it might be the expression of deeply wrongheaded commitments and backward incentives felt by a relatively small group of lawyers. This makes the problem both easier and harder to tackle. To the extent that the goal of professional discipline is deterrence, this suggests that lawyers outside that narrow, committed core may well be easily deterred from engaging in conduct like Eastman’s or Powell’s. But deterring that core—not just by the threat of bar discipline, but by criminal prosecution as well—could prove difficult. Clark, for example, has made himself somewhat of a rising star within the pro-Trump movement not despite but because of his many travails.

Still, bar disciplinary authorities have emphasized their sense of the moral and political importance of their work, both for defending the honor of the profession and for maintaining public faith in the integrity of democracy—which they see as interlinked. “All of us practice law within the structure of a democratic form of government constrained by the Constitution,” wrote the D.C. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, arguing for Giuliani’s disbarment. But that form of government “will not survive if people lose faith in election results.”

After years of waiting for those who sought to overturn the 2020 election to be held responsible, it’s somewhat surreal to watch the sudden pileup of different institutions in different jurisdictions seeking accountability in different forms. The criminal prosecutions have taken a long time to get moving. But so, too, did the bar investigations, which now find themselves eclipsed by upcoming trials. Whatever punishment bar authorities choose to mete out, the professional fate of these lawyers may be determined instead by what happens in criminal court: In many jurisdictions, a felony conviction results in automatic disbarment or suspension of one’s license.

Of the Watergate lawyers who faced criminal charges, most were blocked from practicing for at least some time, and a number—including Dean—were outright disbarred. Some, though, continued battling for their membership in the profession. John Mitchell, Nixon’s disgraced attorney general, found himself disbarred in New York following his conviction for obstruction of justice, conspiracy to defraud the United States, and false statements made to Congress and the grand jury. After he filed an appeal of his conviction—which would ultimately be unsuccessful—Mitchell likewise asked the New York courts to reinstate his license, arguing that he ought to be able to practice law while his appeal was pending. A New York appellate court, ruling in 1976, denied his request. For Mitchell “to continue to appear in our courts and to continue to give advice and counsel,” the court wrote, would “invite scorn and disrespect for our rule of law.”