The Situation: So Much Worse Than You Thought

The Situation over the weekend and on Tuesday considered my encounter with the United States Secret Service outside the Russian Embassy when I tried to use chalk to create a Ukrainian flag on the sidewalk.

Today, I want to describe another encounter I had last week—one that actually rattled me more than being prevented by armed federal law enforcement officers from drawing on the sidewalks—with two old friends.

This encounter took place at a conference at the Watergate Hotel on “Liberalism for the 21st Century,” which was convened by The Unpopulist. I was moderating the first panel of the conference, which featured Francis Fukuyama of Stanford University, Ruth Marcus of the New Yorker, and Lawfare co-founder Jack Goldsmith of Harvard Law School. We had a remarkable discussion of a number of issues, and I encourage people to watch the entire panel. But the most arresting moment—the reason I am writing my column about it—took place near the end, when I asked Marcus and Goldsmith to respond to what I described as a provocation.

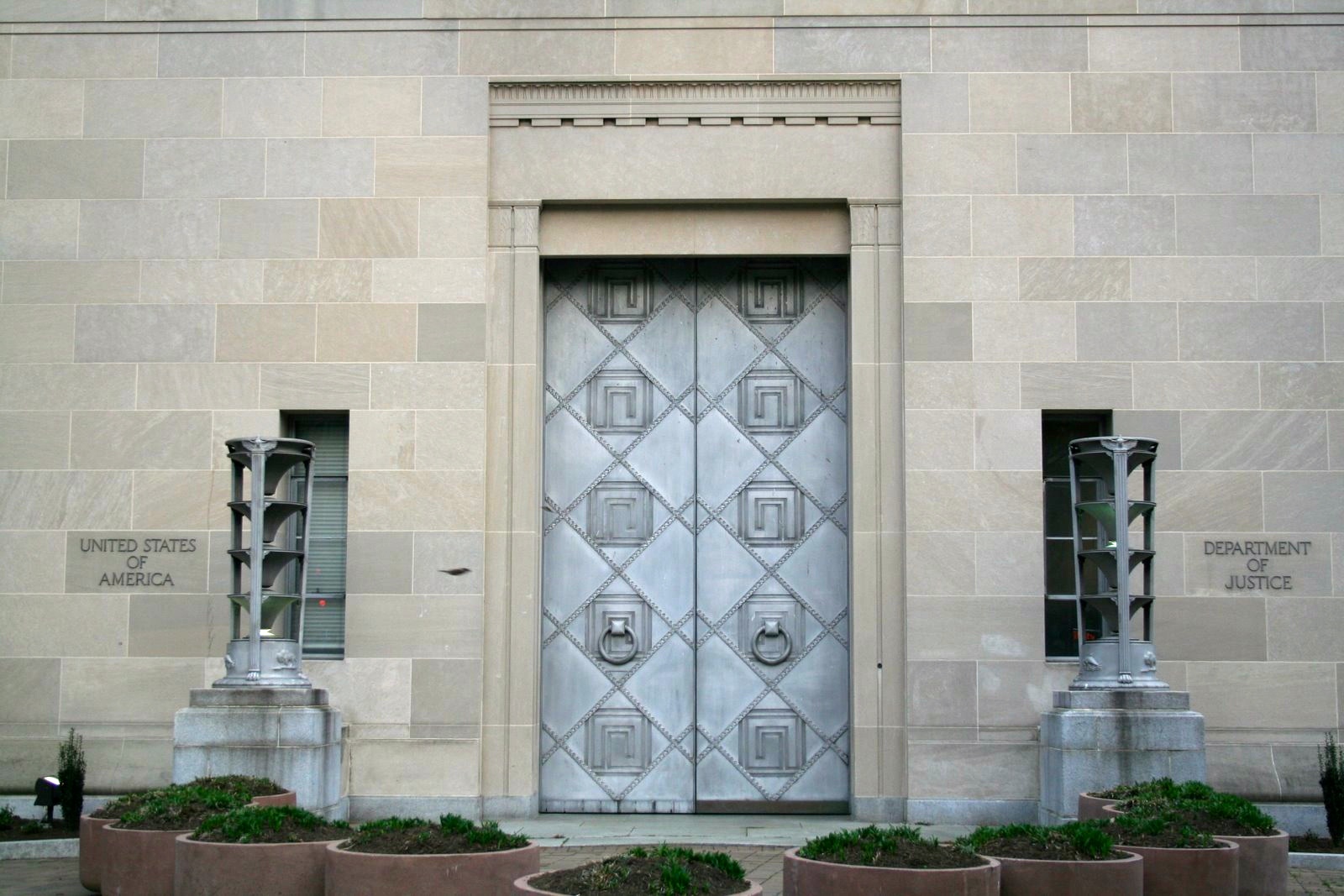

“The pointy end of the spear in any effort to weaponize the government is the Justice Department, both because, in an offensive sense, it prosecutes cases and investigates cases, but also because, in a defensive sense, when you shake down Harvard University and Harvard sues you, it is the Justice Department that is going to defend that,” I said to Marcus. “My general impression is that the magnitude of the changes in the Justice Department are breathtaking, and it is very hard to overstate how impactful the last seven months has been.”

“Particularly at the FBI,” I went on, “it is much worse than is public. There are large parts of the Justice Department that are decimated of personnel and, frankly, there’s an inverse relationship between the quality of the personnel and the likelihood that they’ve left or are leaving. I’m curious, in your reporting for this story, is it any better than my admittedly hyperbolic characterization?”

Now Ruth Marcus is a sober and serious Justice Department watcher—one of the very best—but she is also gently to my left politically and tends to be a little more alarmed than I am on matters related to the Supreme Court and the justice system more generally. She had also just written a Pam Bondi profile for the New Yorker and had thus spent a lot of time recently marinating in Justice Department waters. So I was not entirely surprised when she outflanked me and responded, “Oh, it’s so much worse. You’ve completely understated it.”

Ruth pointed out that “70 percent of the Civil Rights Division is gone. Half the career lawyers in the solicitor general’s office are gone. Half the lawyers in the office that defends the federal government against these lawsuits are gone at precisely the wrong time for the administration.”

She also posed the important question of “in the next administration that comes—because there will someday be a Democratic president elected—what does an attorney general in a Democratic administration do? Does he or she then purge the people who have burrowed in in that administration? Are we just in this endless cycle of retribution?”

And she pointed out—again, quite rightly—that Pam Bondi is a very different animal as attorney general from any of her Trump-era predecessors:

This Justice Department conceives of itself in an entirely different way: Its job is simply to achieve the goals of the administration, no matter what. The president was frustrated by his first attorney general, [Jeff] Sessions. He was frustrated by his second attorney general, William Barr. He picked Pam Bondi for a reason. He is getting what he wanted, which is: full steam ahead. There are no people at the Justice Department telling him, ‘Mr. President, you really can’t do this,’ because they wouldn’t last if they did. And that is another really important internal constraint that is gone.

I then turned to Goldsmith, genuinely expecting he would tell both me and Marcus to calm down. Goldsmith, as readers of this site know well, is often apt to push back against people like me and Marcus when he thinks we are overreacting. In this same panel, for example, he defended the work of the Supreme Court over the last months. As a general matter, his alarm-o-meter runs lower than mine does, even as mine—as I say—runs a little lower than Marcus’s. So I endeavored to warn the audience, which was hotly alarmed, that it might get an opinion from Goldsmith that was challenging and that it should hear him out and take his views seriously.

I began by pointing out that Goldsmith is better sourced at the Justice Department than any journalist and explaining the reason for this. “One thing that you all should know about Jack Goldsmith is that he has trained half the Justice Department,” I explained. “And he is an exceptionally beloved teacher. I cannot tell you how many people come to me and they know me as the guy who did Lawfare with Jack.” I was trying here to give Goldsmith room to say something that might not be what the audience wanted to hear from him but that people should hear out. “You have a lot of contacts in the Justice Department from students there. Is Ruth overstating the matter?”

Yet just as Marcus had outflanked me, Goldsmith now outflanked her.

“No, she’s not,” he said. “In fact, I would say it’s even worse than Ruth described. It’s basically like an atomic bomb dropped on the Justice Department.”

He went on:

I want to underscore something Ruth said: There are tens of thousands of lawyers in the executive branch, spread out, whose job is to ascertain the massive array of laws that [are] supposed to govern executive branch behavior. And you can be cynical about this system, but it always worked, including with the Justice Department, in keeping the White House and the senior executive agencies more or less within the law, with some exceptions. And this administration has systematically and ruthlessly and successfully eliminated, with one exception, all internal legal resistance.

It is simply not acceptable to offer an opinion contrary to the one that the president, who is not a lawyer, wants to push. It’s really an extraordinary thing.

He then flagged the one exception:

The exception is the solicitor general’s office. This is an amazingly interesting fact: The solicitor general is the branch of the government that argues before the Supreme Court. And it has a very conservative solicitor general. But the solicitor general has quite clearly told the White House: We have to play different and play nice with the Supreme Court.

And they have been playing different and playing nice with the Supreme Court, in ways that are not on board with the way the rest of the Justice Department works. And it’s a remarkable testament to how important the Court is seen even by the Trump administration. So I know that there is independent judgment being brought to bear in that office.

But the rest of it has been decimated in terms of personnel and in terms of independent legal judgment.

I have a few observations about this exchange. The first is just how extraordinary it is to have three veteran Justice Department watchers of diverse politics—none of us alarmists, all of us believers in the broad institutional continuity of the department across changes of administration and ideology—tripping over each other to describe the magnitude of the earthquake that has struck the department. I want to stress that we did not consult in advance about this question, at all. My praise of Goldsmith was intended to give him space to disagree with me and Marcus if he chose, not to buttress his doubling down on our points. You should understand this exchange, therefore, as three longtime students of the institution expressing unified alarm at where it is heading and how quickly it is heading there.

Second, this point has obvious implications for the courts. The Justice Department is the ultimate repeat player in federal courts. It prosecutes every case. It defends federal policy. It protects the federal till. Its credibility before the courts matters deeply. And it thus has a different relationship with the courts than other litigants.

This relationship has already begun to erode. Federal judges are showing open skepticism of Justice Department claims in any number of cases. That relations will—and certainly should—continue to erode to the extent judges become convinced that, as Marcus put it, “There are no people at the Justice Department telling him, ‘Mr. President, you really can’t do this,’” or as Goldsmith put it, “It is simply not acceptable to offer an opinion contrary to the one that the president, who is not a lawyer, wants to push.”

If judges come to believe that, they also necessarily come to believe that they are—and this is an amazing fact—the first independent lawyer to review the government’s action or policy who is actually allowed to raise legal questions. No presumption of regularity or good faith can possibly attach when a judge believes that. Indeed, when a judge believes that, a litigant needs to expect the closest of close look legal review.

Finally, Marcus’s point about how one can rebuild the department when this long national nightmare finally ends is critical. But the question actually goes deeper than her formulation of it allows. In Marcus’s formulation, the problem is all about whether we have returned to the Jacksonian spoils system and have jettisoned 150 years of civil service protection law. Is the right response to the Trump-era purge a purge of the new administration’s own? And that is certainly part of the question.

But alongside it, we have to ask other questions, too: Should the next administration investigate those who are currently abusing the grand jury system and other investigative instruments of the department for openly political purposes? Should it look into those—like Ed Martin, for example—who are using their Justice Department positions to threaten people with investigation or to look into the people who are shaking down universities and law firms on the administration’s behalf?

Should the goal, in other words, be the reestablishment of the modern norms of Justice Department conduct and how can one reestablish and then maintain those norms when one of the two dominant political movements in the United States has declared war on them and has actively sought their destruction? Asymmetric norms don’t generally work very well.

But if not the reestablishment of the traditional norms of apolitical administration of justice, what then is the strategic vision, and how on Earth can one square it with such notions as equal justice under law?

I have no idea what the answers to these questions are. But it strikes me as essential to start thinking about them now.

The Situation continues tomorrow.