To Evade Sanctions, the Kremlin Turns to a Convicted Money Launderer

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to reflect reporting about a recent Russian Finance Ministry announcement.

Why would a bank hire a convicted thief to run a payments company?

This was the question I kept returning to as I was investigating A7, a Russian cross-border payments service specifically designed to enable large-scale sanctions evasion, and its associated cryptocurrency A7A5. A7 was officially launched by Promsvyazbank (PSB), a heavily sanctioned Russian state-owned military bank, in October 2024. In a press release announcing the launch, PSB called A7 a “unique settlement mechanism” that would “support Russian participants in foreign economic activity and their trading partners in the face of anti-Russian sanctions pressure.” A7 is also financially backed by VEB.RF, a key Russian state development institution.

It’s not surprising that state-owned PSB and VEB.RF want to enable sanctions evasion for Russian businesses, especially when faced with Russia’s worsening economic situation. A7 has received public backing from the highest levels of the Kremlin, including Putin himself. But here’s the weird thing: A7 is led (and majority owned) not by a Russian banker or bureaucrat but by a convicted criminal named Ilan Shor.

Shor is a former Moldovan banking executive who was convicted of fraud and money laundering in 2014 for a scheme in which he and his associates siphoned a billion dollars out of several Moldovan banks via a complex network of foreign shell companies. While under house arrest, he escaped from Moldova in 2019, fleeing first to Israel and then to Moscow.

In the years since, Shor appears to have become a figurehead in what Moldovan officials claim is an industrial-scale political interference scheme in support of pro-Russian parties and political influence in Moldova. The allegations by Moldovan law enforcement and intelligence officials include vote-buying and other forms of illicit political finance; staged rallies and paid protesters; coordinated inauthentic social media campaigns; and a range of other activities. Recent investigations by the BBC and others have exposed what appears to be a sprawling campaign run by Shor’s nongovernmental organization Evrazia.

The Kremlin’s interference efforts in the lead-up to Moldova’s parliamentary election on Sept. 28 were so intense that President Maia Sandu publicly warned that her country’s independence was at stake. Ultimately, the elections were a win for the pro-European voices in Moldova and a blow to the Kremlin’s ambitions.

While all of this was going on, however, Shor was also up to his neck in a different kind of skullduggery: heading up A7’s efforts to enable billions of dollars in sanctions evasion. At the Far Eastern Economic Forum in September 2025, Shor claimed that A7 had facilitated over 7 trillion rubles (about $86 billion) in transactions in less than a year of operating. If true, this would equate to roughly 11.8 percent of Russia’s foreign trade in that time period. The company has opened multiple offices across Russia and the occupied Ukrainian territories. According to import payment figures included in an A7 presentation in August, the overwhelming majority (78 percent) of A7’s payments are going to or coming from China.

In September, Russian President Vladimir Putin personally oversaw the opening of A7’s Vladivostok office to focus on trade with Asia. Shortly after, A7 opened its first public international offices in Nigeria and in Zimbabwe, with opening ceremonies attended by the finance ministers of both African nations as well as the local Russian ambassadors and the Russian deputy finance minister.

Meanwhile, as detailed in my earlier investigation published in June, A7 was busily building out its operations in Kyrgyzstan. This included creating their own cryptocurrency, A7A5. A7A5 was billed as the world’s first stablecoin pegged to the ruble and is supposedly backed one-to-one by fiat ruble deposits held in PSB bank accounts. An investigation by the cryptocurrency tracing company Elliptic has estimated that roughly $8 billion in stablecoin transactions have moved through wallets likely owned by A7 in the past 18 months (although it is not entirely clear what these transactions represent; a Financial Times investigation found very strange patterns of trades that do not reflect normal trading behavior). A7A5 was recognized as Russia’s first official digital financial asset on Sept. 30, making it the first cryptocurrency in which Russian businesses can legally conduct foreign trade.

This activity has not escaped the notice of Western governments. A7, its subsidiaries, and the Kyrgyzstan company Old Vector, the official issuer of A7A5, have all themselves come under sanctions from the U.S. and U.K. in recent months. On Oct. 24, the EU also levied sanctions against A7 and Old Vector, and banned transactions involving A7A5 across the EU. So far, A7’s attitude has been to scoff that the sanctions will have no impact on their work. It’s not clear what the actual level of impact has been, but it is evident that so far the sanctions have not stopped them from being able to operate. A Financial Times analysis in October found that the equivalent of roughly $6 billion had moved through cryptocurrency wallets linked to A7A5 (although, as noted above, it’s not entirely clear what this movement actually represents).

A7 is a big swing for PSB. They’ve invested massive amounts of both actual monetary capital and political and reputational capital into making this endeavor work. It’s potentially high reward, but it’s also high risk.

So this again raises the question: Of all the people you could pick to run this important new project involving billions of dollars, why would you choose a convicted criminal fraudster and money launderer like Ilan Shor?

In my latest investigation, I think I’ve landed on the answer. Who better than a criminal to help you launder money across borders?

The key finding is that A7 appears to be using an international network of shell companies to move its clients’ money globally via a form of trade-based money laundering. This conclusion is based on internal A7 documentation that has been publicly uploaded by Russian regional governments and shared on Telegram; digital forensic investigations that enabled me to identify at least 10 of A7’s foreign shell companies, mostly based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE); and social media discussions between Russian importers-exporters.

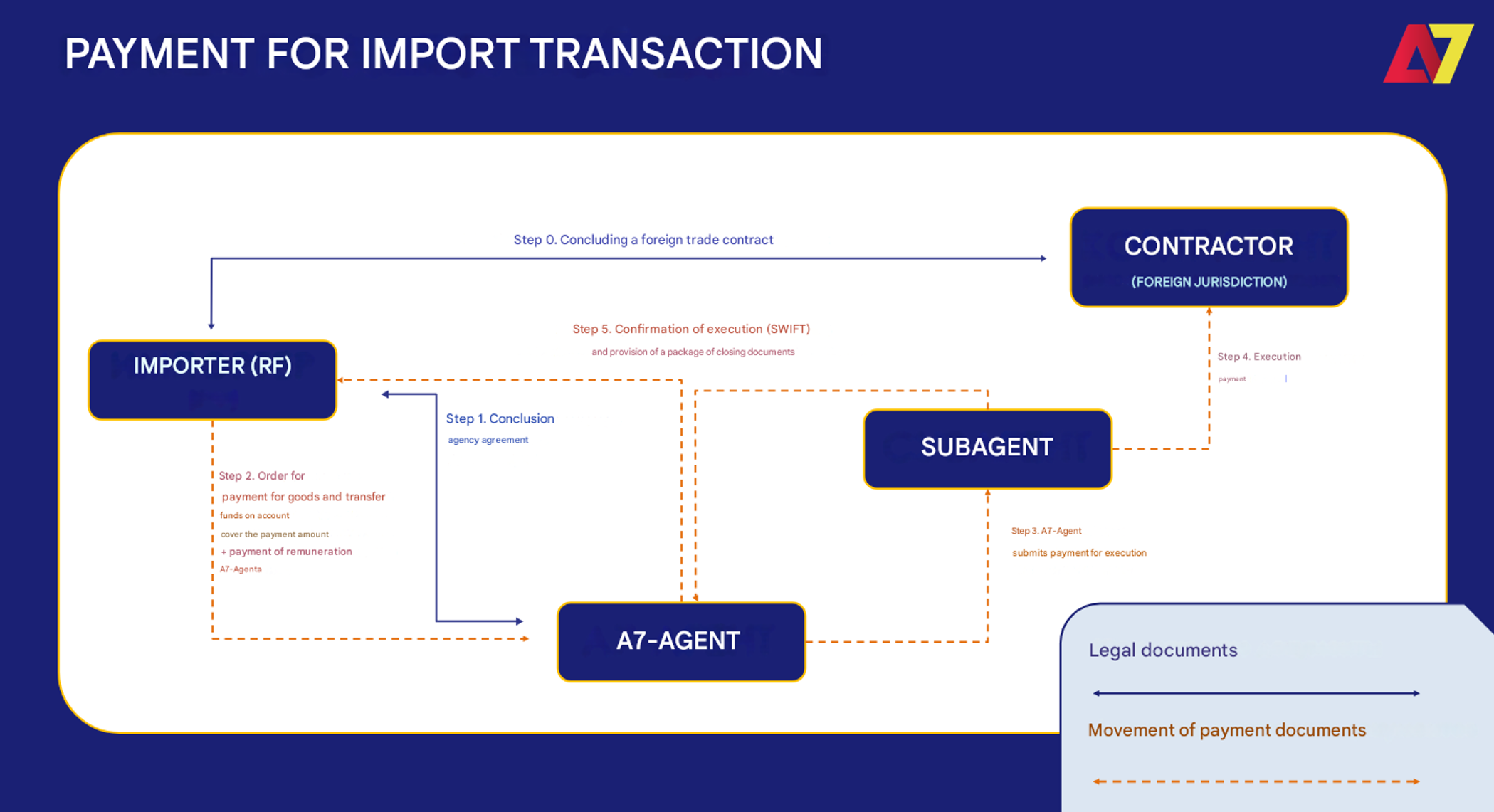

Here’s an example of how it works (see Figure 1): Say that a Russian company is seeking to import electronics from China and needs to make a payment to the Chinese supplier. If it is unable to make the payment directly due to sanctions, it can sign a contract with A7 (or its subsidiaries A7 Agent and A71). It then pays A7 the amount for the supplier plus A7’s fees in rubles in Russia. A7 communicates to its “subagent,” that is, a shell company in a foreign jurisdiction, perhaps the UAE.

The UAE company falsifies documents to make it appear as if the Chinese supplier is selling to the company rather than the real Russian buyer—in order to avoid raising the suspicions of banks or financial authorities—and then makes the payment to the supplier. The process for export payments is essentially the same in reverse, albeit slightly more convoluted.

Figure 1. Screenshot from an A7 presentation for potential clients, showing import payment flow (auto-translated with Google Translate).

This process of systematically obscuring the true origins and destinations of payments by layering them through a series of offshore shell companies and false documentation is often associated with money laundering. It is also strikingly reminiscent of how Shor pulled off his earlier theft of a billion dollars from Moldova’s banking system.

What Shor and A7 have built is a system that is markedly similar to the large-scale Russian criminal money laundering network known as the “Global Laundromat,” which has been exposed in recent years and in which Shor himself was directly implicated.

Unlike that network, however, A7 is backed by both the financial resources and the political heft of Russian state institutions. The money has enabled A7 to grow incredibly fast; the political backing appears to be opening doors. For example, the presence of the Nigerian and Zimbabwean finance ministers at the openings of A7’s offices suggests that the African governments are aware that A7 is not an ordinary business.

Russia’s worsening economic situation may be driving the Kremlin’s willingness to throw its weight behind a project like A7. A7’s fusion of suspect techniques with state resources geared toward enabling sanctions evasion at scale has echoes of Iran’s shadow banking system. This hybrid operation has allegedly allowed A7 to move tens of billions of dollars in violation of sanctions—but it also creates unique weaknesses.

If A7’s operations are in fact criminal, they would obviously be vulnerable to traditional law enforcement mechanisms: sanctioning shell companies, freezing bank accounts, and indicting individuals facilitating criminal acts.

The challenge facing A7 is that it is trying to attract clients who are not criminals—with methods that are often associated with criminal activity. Criminals laundering money have limited options and a high tolerance for risk; legitimate businesses do not. This makes trust, or lack thereof, a key chink in A7’s armor.

Comments in Telegram groups for Russian importers-exporters reflect a notable level of skepticism about A7, raising questions about its opaque methods, suspiciously low fees, and circuitous payment routes. They also point dubious fingers specifically at the involvement of Ilan Shor, asking whether an organization led by a convicted thief can really be trusted with their money.

The success of A7 also depends on foreign counterparts being willing to take the risks of working via this network. Foreign suppliers and buyers have to be willing to accept transacting via shady intermediaries with possibly false documents in odd jurisdictions, with no real guarantees that their money will end up where it needs to be nor options for redress if it goes wrong. If foreign counterparts refuse to go along with it, A7’s entire business model would be in real trouble.

In addition to law enforcement action, then, simply raising awareness about the nature of A7’s operations and the potential risks for foreign counterparts—from the possibility of funds being seized to the legal risks to themselves of participating in a money laundering operation—could have a significant impact on A7’s capacity to operate.

Similarly, increasing awareness about Shor’s criminal history could raise serious questions in the minds of foreign counterparts. Is a man who stole a billion dollars in client funds really the person they want to entrust with their own money?

A7’s value to the Russian state is its dual nature: its ability to simultaneously act as a legal, legitimate business within Russia and perhaps as an illicit money laundering network outside of it. These fused halves of the A7 operation bake in inherent weaknesses as well as strengths. With the right pressure in the right places—where the licit and the illicit parts of A7’s operation butt up against each other—A7’s network could yet fall apart under the weight of its own internal contradictions.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d27bd863_5)