Understanding Conflict Through Satellite Imagery

In recent years, high-resolution satellite imagery and geospatial analysis have become increasingly valuable tools in documenting the effects of conflict, including the widespread destruction of infrastructure, property, and lives in Ukraine, Gaza, and Sudan. In January, satellite imagery played a pivotal role in the U.S. Department of State’s determination that members of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied militias had committed genocide in their attacks against non-Arab communities in several locations in Sudan. Most recently it has been used to document the damage caused by missile and drone strikes in the ongoing India and Pakistan conflict.

Conducting research on sensitive or contentious issues in fragile and conflict-affected areas where demographic data is flawed, access to remote and insecure areas is challenging, and representative samples prove particularly elusive is a perennial problem. In these terrains, fieldwork is typically limited and skewed by security concerns and the associated costs, and it is often the voices of elites that are the loudest and most prominent. The Farsi phrase “Can hearing ever be like seeing?” reflects the greater weight that should be given to the things we can see for ourselves, compared to what we are told.

To this end, satellite imagery and informed analysis can be usefully deployed to study complex and sensitive issues in fragile and conflict-affected areas and support more effective policy development. While imagery is not a substitute for talking to the people directly impacted by conflict, our research on the outbreak of heavy fighting between Iran and Afghanistan in May 2023 shows that it is a critical tool in developing a better understanding of these complex terrains, where the loudest voices can dominate the media and social landscapes and skew research findings—and, all too often, policy outcomes.

Background to the Conflict

In May 2023, heavy fighting broke out between Iranian and Taliban forces on the border between Afghanistan and Iran. At the time, the media and many analysts looked to explain the incident as a result of the escalating “war of words” in the week before between senior officials in the Taliban and the Iranian Republic.

As is common during dry years, the Iranian authorities complained that Kabul had retained more than its fair share of water from the Helmand River, depriving farmers and communities across the border in the province of Sistan and Baluchistan in Iran. Under a treaty signed by the two nations in 1973, the water is a shared resource. The Iranian president at the time, Ebrahim Raisi, warned “the rulers of Afghanistan to give the water rights to the people of Sistan and Baluchestan,” prompting responses from senior Taliban officials.

Rather than focusing on the rhetoric surrounding the dispute, our research revealed novel insights into the conflict by focusing on concrete facts that could be observed through satellite imagery. Our research pointed to a more localized dispute about border management and the challenges of recalibrating cross-border relations following the collapse of the Afghan Republic and the subsequent Taliban takeover, and revealed far more pervasive issues with the widespread and unsustainable exploitation of groundwater across the Helmand River basin.

Disparities Between Observation and Discourse

The use of geospatial analysis in our research helped us better understand the accuracy of the competing narratives that authorities in Tehran and Kabul look to convey when complaining about transboundary water rights in the Helmand River Basin.

Typically, disputes between the two countries begin with the Iranian government accusing authorities in Kabul of withholding water from the Helmand River and failing to comply with their treaty obligations. Kabul authorities generally suggest the reduction in water flow is a function of drought, noting that there is a provision in the Helmand Treaty to reduce water flows under such conditions.

Tehran alleges that Afghanistan’s ability to store and divert water—through infrastructure projects such as the Kajaki Dam, constructed in the 1950s, and more recently the Kamal Khan Dam, built in 2021—has prevented sufficient water from being discharged into Iran for use by the population of Sistan and Baluchestan.

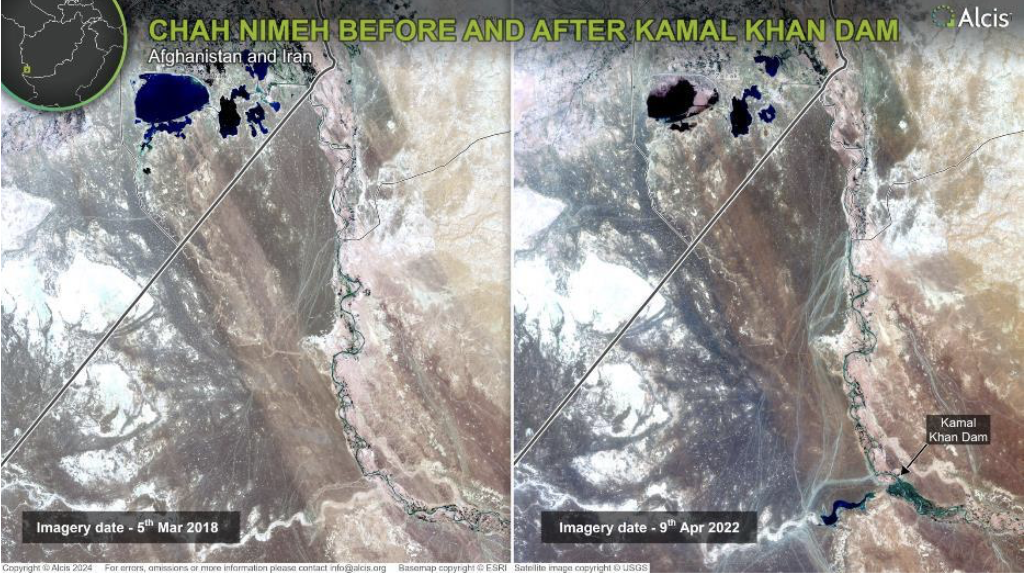

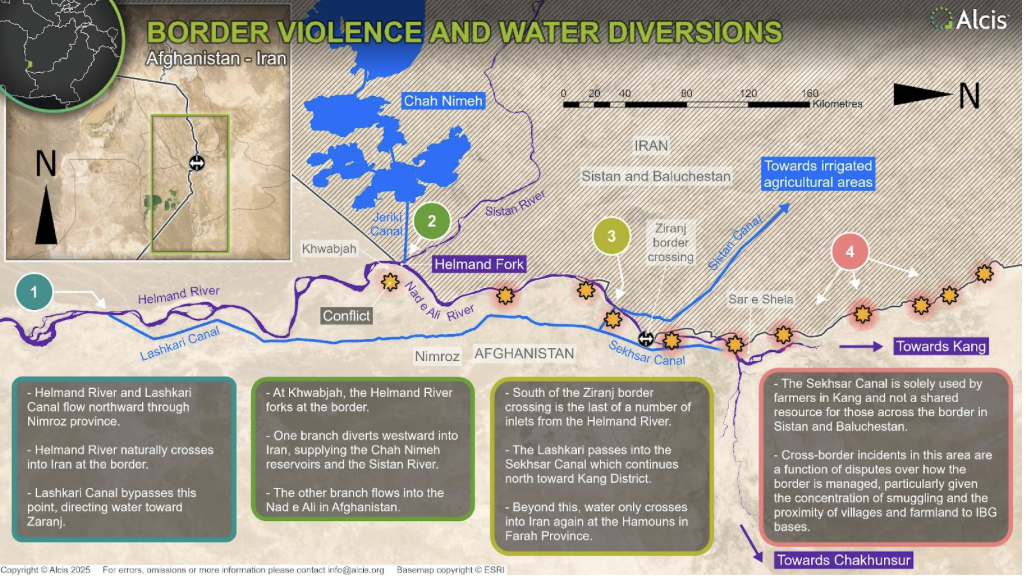

There is some truth to this complaint, especially since the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam. As satellite imagery has shown, this latest dam, constructed in the lower part of the Helmand River Basin—just upstream from the Helmand fork—now allows Kabul to release water from the Kajaki Dam in the upper basin to be used by communities downstream in Afghanistan while retaining any remaining discharge at Kamal Khan, and preventing it from flowing to Iran (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chah Nimeh before (2018) and after (2022) the commissioning of Kamal Khan Dam. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

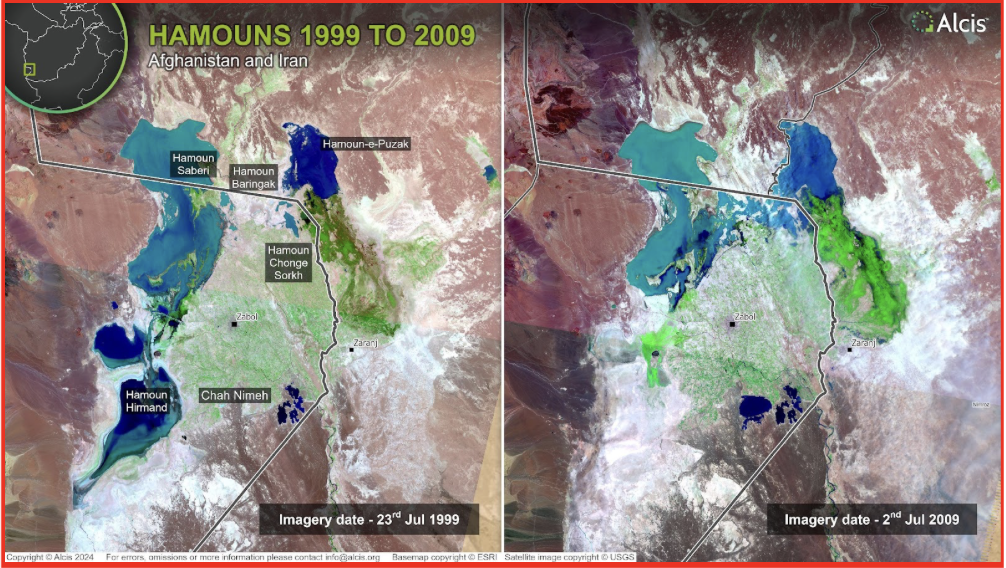

Further imagery analysis has shown that any efforts by the Afghan authorities to retain and divert water have been mirrored on the Iranian side of the border—often, some years earlier. For instance, the Jeriki Canal and Chah Nimeh reservoirs in Iran, located after the Helmand fork—where the Helmand River first meets the Iranian border—were initiated in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively, to divert and store water, mainly for the urban populations of Zabol and Zahedan. Before the construction of the Kamal Khan Dam in Afghanistan, these reservoirs captured the water once released from the Kajaki Dam. The construction of the Chah Nimeh 4 reservoir in Iran in 2008—which more than doubled storage capacity—subsequently significantly reduced the water flow into the Nad-e-Ali River and Hamoun-e-Puzhak in Afghanistan, and the Hamoun-e-Saberi in Iran (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact of construction of Chah Nimeh 4 on the hamouns. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Consequently, while historically Tehran has argued that it is Kabul’s failure to release water from Kajaki that limited water flow to the hamouns—a series of terminal lakes and salt marshes—and Sistan and Baluchestan province, its own infrastructure efforts at the Helmand fork have been more detrimental to the rural livelihoods of the downstream populations in both Afghanistan and Iran. Indeed, Iranian authorities tend to prioritize the populations of Zabol and Zahedan; water is released from the Chah Nimeh reservoirs to farmers in Sistan and Baluchestan for irrigation only after the needs of the urban population have been met.

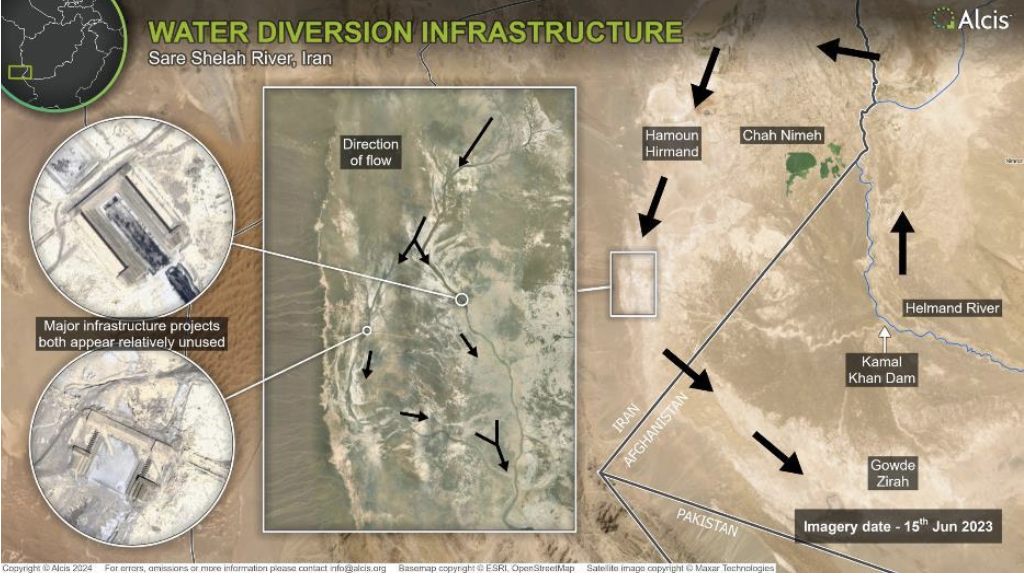

Through imagery analysis, it is also clear that Tehran sought to stem the flow of water from the Hamoun-e-Hirmand through a series of dams on the Sar-e-Shelah River in the district of Hamoun in Sistan and Baluchestan province (Figure 3). As such, while Tehran accuses Kabul of seeking to retain and divert water to its advantage and to the detriment of downstream populations in Iran, Tehran has been doing the same for longer and—until the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam—perhaps more effectively. While Tehran’s complaints have intensified since the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam, it is inaccurate for Tehran to portray itself as the sole victim and Kabul as the sole perpetrator.

Figure 3. Dams on Sar-e-Shelah River constructed circa 2001, redirecting water from flowing toward Gowd-e-Zirah. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

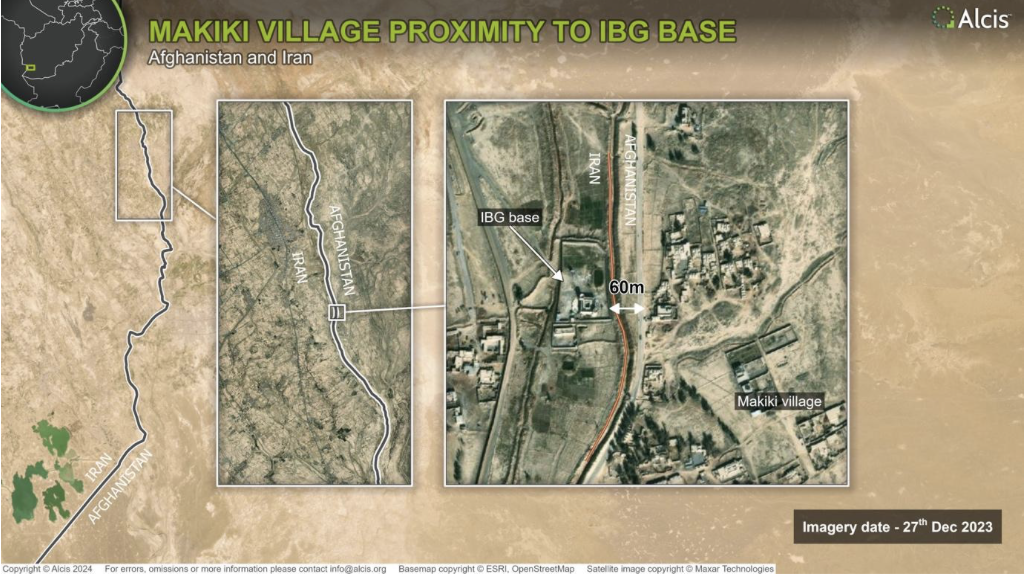

Imagery analysis also revealed that the fighting between Afghan and Iranian forces began in an area where the border populations do not even share common water sources but rather where there is a long tradition of cross-border smuggling (Figure 4). It shows just how close the Iranian border wall is to Afghan farmland and villages, often as little as 60 meters apart. The construction of this border wall increased the potential for the Iranian Border Guards (IBG) to fire across the border and, following the Taliban’s capture of Kabul, increased the likelihood that their battle-hardened soldiers would return fire.

Figure 4. Water flows on the border from Kamal Khan to Kang. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Further satellite imagery exposed the increased number of catapults used to propel drugs into Iran along this stretch of the border following the Taliban takeover, an indicator of their tolerance of the cross-border trade—a source of increasing frustration among the IBG and, ultimately, the direct cause of the fighting (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proximity of farmland to Afghan border posts and Iranian border gates near Makiki village. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Implications of Reduced Surface Water

Perhaps most important, satellite imagery and geospatial analysis were instrumental in identifying how communities in Afghanistan and the Iranian state have responded to a reduction in surface water in the Helmand River Basin through widespread groundwater exploitation and the threat this now poses to the lives and livelihoods of communities across southwest Afghanistan and in Sistan and Baluchestan in Iran.

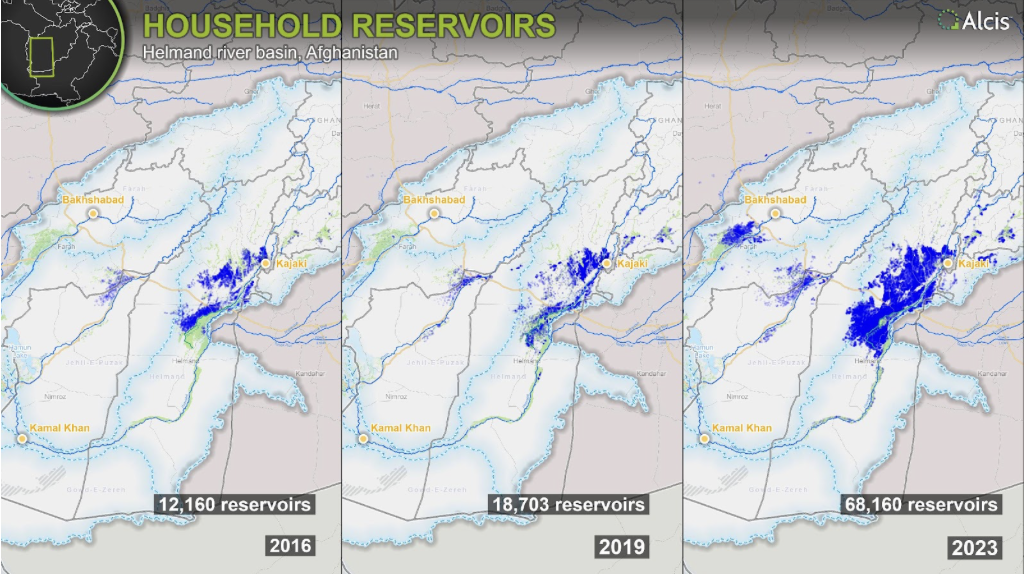

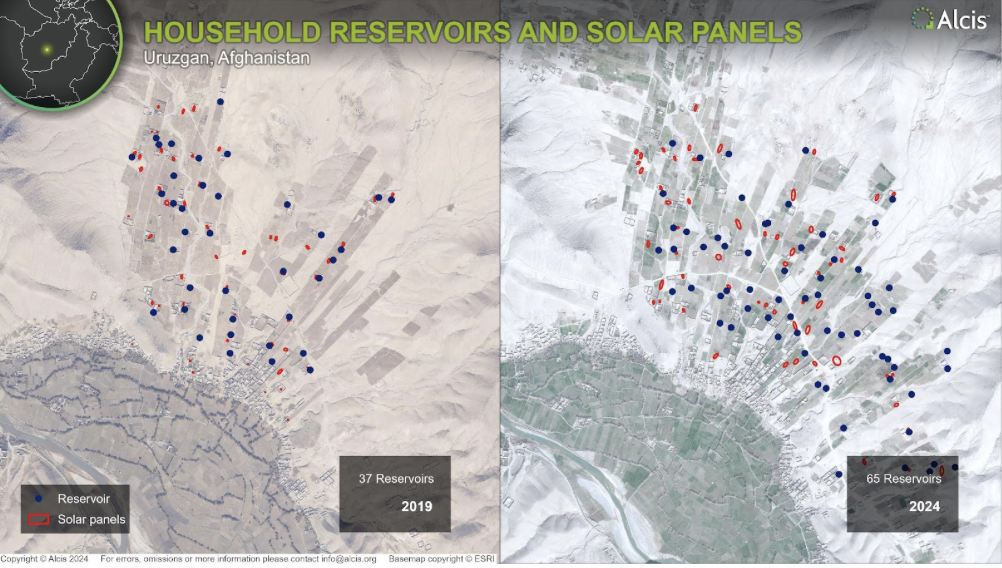

In Afghanistan, access to affordable solar-powered systems has been transformative and has led to ever greater numbers of Afghan farmers installing deep wells and extracting groundwater. Only a meter in diameter, many wells are more than 100 meters in depth and have water drawn from them using a pump powered by multiple arrays of solar panels. While underground, these wells often leave a visual signature—a surface reservoir and solar panels—that can be identified and then mapped using imagery (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Household reservoirs used by those using solar-powered deep wells to extract groundwater (2016, 2019, and 2023). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Imagery shows that by 2023, there were at least 68,160 deep wells in the Helmand River Basin—five times more than in 2016. While these were at one time used only by farmers looking to settle remote former desert lands in the southwest provinces of Helmand and Farah—often to grow poppies—these deep wells have become ubiquitous, commonly used in surface-irrigated areas where water flows have become increasingly unreliable due to climate change.

In areas formerly irrigated using traditional irrigation systems—karez—increased temperatures and less precipitation in the Helmand River Basin resulted in reduced water flows and a move to deep wells. As the number of deep wells increased, the karez dried up completely. With many more deep wells installed, groundwater levels are falling at an alarming rate—in some cases, by as much as five meters per year. Some of the earlier, shallower wells dug in the initial years of settling the former desert lands of the southwest have failed, resulting in deeper wells being installed in ever-increasing numbers (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The expansion of groundwater wells in Uruzgan (2019 and 2024). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

In southwest Afghanistan, farmers are increasingly reliant on their deep wells for irrigation and drinking water, leading to increasingly neglected surface irrigation systems (which are collectively managed). This shift toward water as a privately owned asset will likely render the water management problem even more intractable.

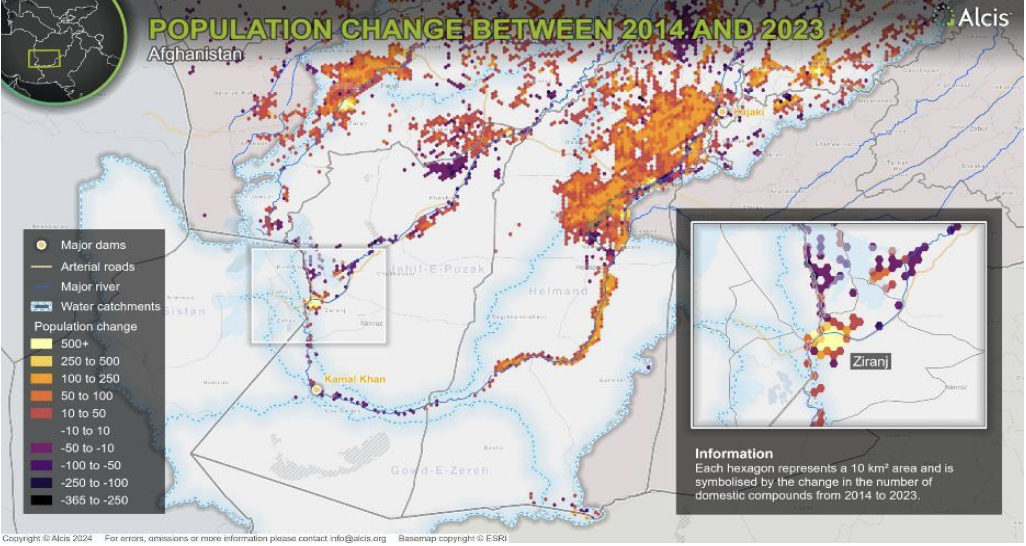

Farmers are aware of the threat this increase in groundwater extraction poses to their ability to continue to draw water, grow crops, and sustain their livelihoods into the future, but they see no other option. In fact, imagery analysis of household compound data shows that over the past decade, population growth in the Helmand River Basin in Afghanistan has coincided with increased groundwater exploitation (Figure 8). Outmigration appears to be restricted to areas that are not only receiving reduced surface water flows due to climate change, but where the groundwater is often salinated and cannot be used for agriculture. This includes districts like Dishu and Charburjak, in the lower part of the Helmand River.

Figure 8. Changing population in Helmand River Basin (2014 to 2023). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

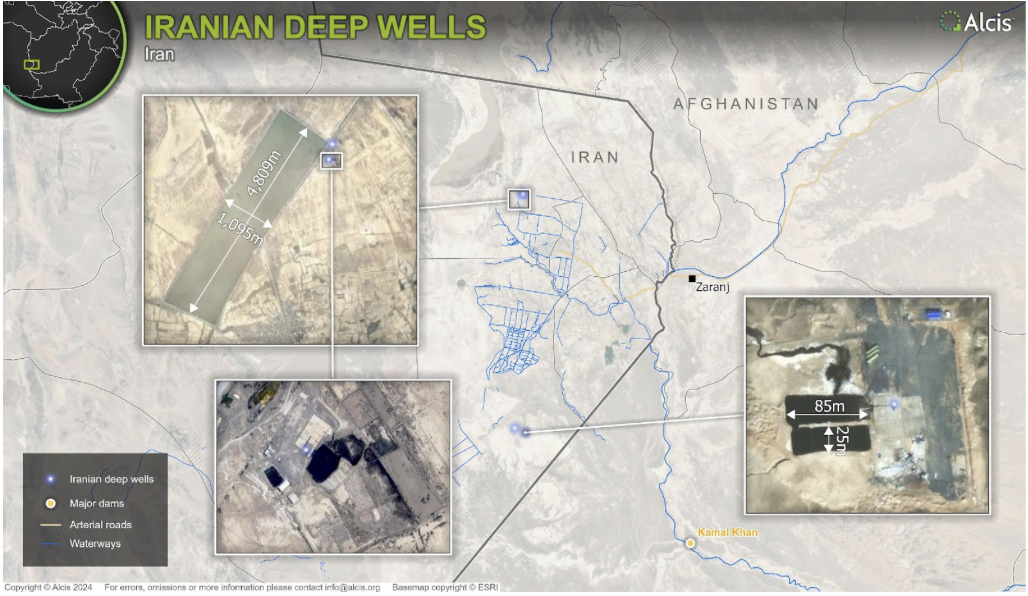

Across the border in Iran, satellite imagery shows the same move to groundwater extraction—however, led by the state and at scale. In Sistan and Baluchestan, we used imagery to identify the location and size of three deep well drilling and water extraction projects (Figure 9). Established in 2019, these wells have been drilled to between 1,000 and 3,000 meters. The reservoir accompanying the well in the district of Nimroz is 27,000 square meters. These three deep wells, as well as the dramatic upswing in groundwater well drilling in the Helmand River Basin in Afghanistan, reflect how state, individual, and community responses to the climate crisis and diminishing surface water sources risk depleting the groundwater that has increasingly become a lifeline for both rural and urban populations in the region; it is literally a race to the bottom.

Figure 9. Location and extent of Iranian deep well drilling operations and water storage (2024). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

The Importance of Using All Faculties

By drawing heavily on geospatial analysis and imagery, our research has gone a long way in recasting and refocusing discussions on transboundary water rights and conflict on the Afghanistan-Iran border. In particular, it has shown the role that Tehran has played in retaining and diverting water from populations downstream, including farming communities in Sistan and Baluchistan—diverging from the narrative that apportions blame solely to Kabul.

Our research has also identified, quantified, and visualized the widespread move to groundwater extraction in the Helmand River Basin in Afghanistan. This trend could, if continued unchecked, threaten the livelihoods of up to 3.65 million people over the next decade. This should spark concern for countries in the region and in Europe, which have often been the final destination for Afghan migrants fleeing war and destitution back home.

By focusing on concrete, observable fact—rather than just discourse—this study has shown that researchers conducting projects in fragile and conflict-affected areas should draw on as many senses as they can to avoid misleading policymakers, while seeking to achieve the best policy outcomes.

This work was funded by the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research program, funded by U.K. international development from the U.K. government. Views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the U.K. government’s official policies.

.jpg?sfvrsn=cb803a66_6)