Understanding Global AI Governance Through a Three-Layer Framework

Global AI governance is increasingly complex and fragmented. The three-layer framework of internet governance can yield powerful insights.

“If the 20th century ran on oil and steel, the 21st century runs on compute and the minerals that feed it.” Thus, the Trump administration’s Pax Silica Initiative, a commitment between the United States and eight partner countries to work together on “securing strategic stacks of the global technology supply chain,” began on Dec. 11, 2025. Two days prior, the Linux Foundation announced the formation of the Agentic AI Foundation (AAIF), a group of artificial intelligence (AI) companies—including Amazon, Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Cloudflare—committed to “lay[ing] the groundwork for a shared ecosystem of tools, standards, and community-driven innovation” for agentic AI, referring to AI tools that can perform a series of tasks autonomously.

These initiatives add to an already fragmented AI governance landscape, with new bodies and working groups emerging periodically and international organizations that produce an increasing number of normative texts and policy papers. Just since 2024 alone, the Council of Europe has finalized the Convention on Artificial Intelligence and a human rights risk assessment methodology for AI; the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has updated its trustworthy AI principles and issued a report with recommendations on the use of AI in government; the U.S. government has launched Pax Silica; the AI Action Summit of 2025 has produced a statement on inclusive and sustainable AI; and the United Nations has established an “Independent International Scientific Panel on Artificial Intelligence” and a “Global Dialogue on Artificial Intelligence Governance.”

With this exponential growth in global AI policy output comes a risk of duplication of initiatives, substantive overlap, interoperability challenges, and even potential contradictions of policy and norms. The sheer number of bodies and initiatives also makes it challenging for AI actors to determine where to best engage in global AI governance in a way that leads to lasting impact. The United Nations has recently recognized the challenges of engaging in this context, emphasizing the need for “multistakeholder AI governance,” yet without specifying what this means in practice, resulting in greater confusion.

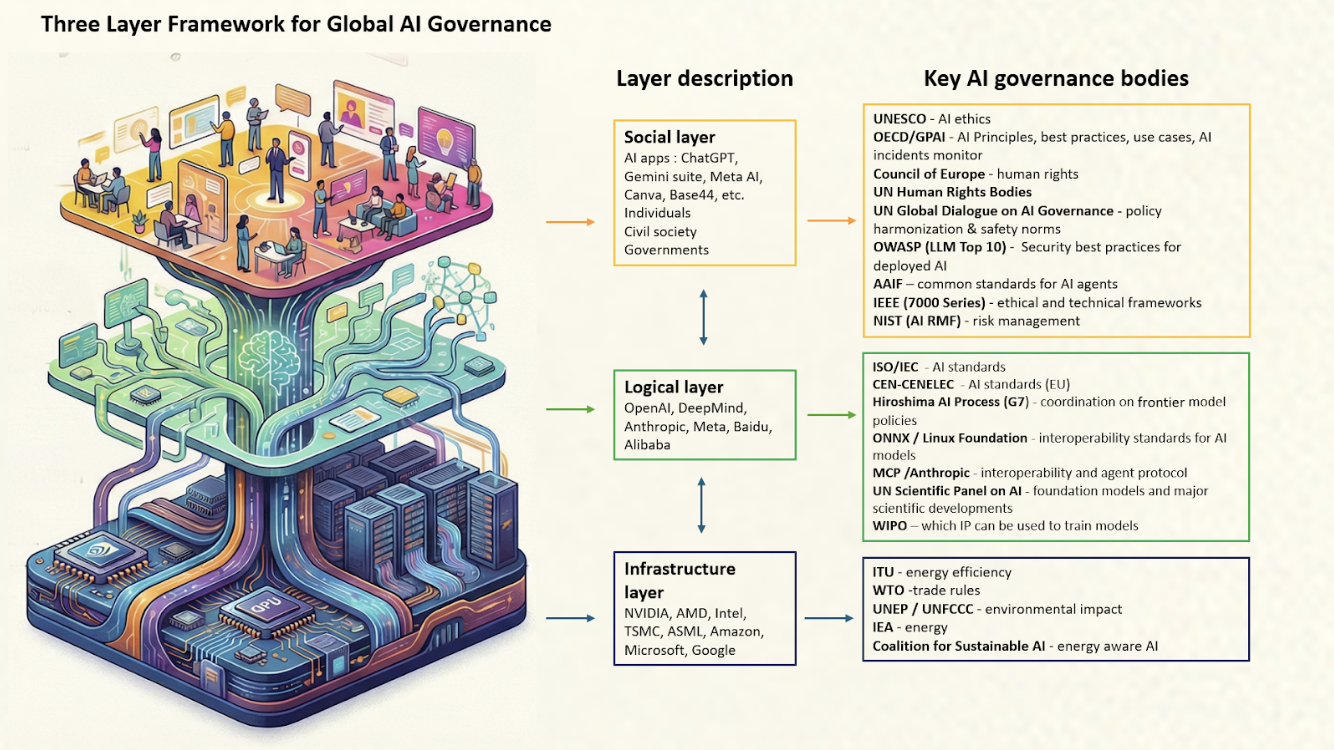

In an attempt to make sense of the current AI landscape, we, the authors, propose a multilayered framework to conceptualize global AI governance based on the widely used three-layer framework for internet governance. It is modeled on common framings of the “AI stack,” specifically the hardware, software, data, and applications forming part of the AI supply chain, as well as its underlying material and energy components. This piece does not purport to establish a definitive framing. Indeed, such a framing would be ill-advised, given the dynamic nature of the field. Nonetheless, we hope it can provide some guidance and direction to better navigate the global AI landscape.

The Three-Layer Framework of Internet Governance

A useful starting point to map the AI governance landscape comes from a 25-year-old framework that remains relevant in scholarship today. In 2000, Yochai Benkler published a seminal paper, “From Consumers to Users: Shifting the Deeper Structures of Regulation Toward Sustainable Commons and User Access,” that distinguishes between the three “layers” of internet activity:

- The infrastructure layer comprises the physical and technical foundation of the internet, such as cables, routers, servers, data centers, and the overall hardware that enables digital communication. Governance at this layer focuses on issues such as access, connectivity, and network reliability.

- The logical layer consists of the software, protocols, and standards that determine how information flows and systems interoperate. Governance here involves the standards that enable interoperability and security across networks and applications. Organizations such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) play a leading role in shaping this layer.

- The content layer is visible to internet users. The activity occurring in this layer encompasses all the human and organizational interactions that occur over the internet, such as content creation, cybercrime, and economic activity.

In 2016, ICANN augmented this framework by indicating how various international organizations are involved in different aspects of internet governance. The following draws inspiration from ICANN’s infographic and proposes a new visualization of global AI governance.

Applying the Three-Layer Framework to AI Governance

Applying the three-layer matrix to AI governance results in the following classification:

- The AI infrastructure layer includes computing and data infrastructure underpinning AI high-performance computing, such as semiconductors, GPUs, TPUs, NPUs, data centers, cooling systems, and cloud computing platforms. One might extend it to include the high-performance computing supply chain, energy systems, and the resources—water, gas, nuclear—required to power them. Semiconductor manufacturers such as Nvidia and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) operate at this layer.

- The logical layer encompasses AI models, software systems, and model-centric services through which AI is developed, accessed, orchestrated, and integrated, including emerging interoperability protocols. In contrast to the internet’s logical layer, built on open and widely shared standards such as TCP/IP, the proprietary foundation models developed by a small number of firms, including OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic, currently dominate the AI logical layer. Meanwhile, this layer also includes important open-source components, such as machine-learning frameworks PyTorch and TensorFlow, model exchange platforms like ONNX, and a growing set of proposed interoperability protocols intended to enable integration and coordination across AI systems, such as Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP).

- The social layer refers to the human and institutional interactions—such as business-to-business, government-to-consumer, business-to-consumer, and consumer-to-consumer—that use AI applications to produce outputs of all types. The list of actors in this layer is staggering, including business-oriented and consumer-facing applications; text, sound, images, and video; coding applications; and AI agents that perform consumer or business tasks. These AI applications are used in a range of social activities, from hiring tools to crime prevention, marketing, and workflow automation. Representative applications include Gemini, ChatGPT, Veo, Napkin, Canva, Base44, and Genspark. They are developed and commercialized by actors of all shapes and sizes. Similar to the internet’s evolution, there’s a democratization of AI tools on the social layer (agents, vibe coding). What unites these applications conceptually is that AI is core to how they operate and produce content, drawing on models and protocols from the logical layer.

Admittedly, other methods exist for identifying activity around the AI stack. IBM proposes, for example, a multilayered scheme of compute, data, model, application, and “observability” layers. AI research firm Gartner applies a more abstract conceptualization with data management, AI applications, and risk mitigation. Urs Gasser includes an ethical layer in his model. Each of these models is valuable in its own way. However, in the context of AI global governance, a simpler three-layer model, similar to the one used by Microsoft’s Brad Smith, where each layer encompasses a broad spectrum of activities, better captures how AI actors realistically view and operate within the AI stack. Furthermore, its parallels to the widely adopted internet governance model allow for points of comparison between global AI and internet governance. The three-layer framework can also be exported to other technological governance topics, such as quantum, brain-machine interface, and robotics, promoting greater interoperability of policy discussions across major technological axes. That said, as will be discussed below, the model may require some expansion.

With a broad outline of the layers of AI activity, the next step is identifying the international bodies relevant to each layer. ICANN’s 2016 visualization of internet governance provides inspiration for mapping out the international bodies influencing each layer of the AI ecosystem. Figure 1 provides an overview of the key international, governmental, nongovernmental, and private-sector institutions relevant to the three layers.

Figure 1. Institutions relevant to the three-layer framework.

Observations and Policy Questions

Certain insights can be gleaned from the visualization in Figure 1.

First, it enables us to cluster various policy initiatives based on the layer where they focus. We can note, for instance, that California’s Transparency in Frontier AI Act, which applies its main provisions to “frontier developers,” focuses on the logical layer. Meanwhile, the Hiroshima Process Code of Conduct refers to “advanced foundation models and generative AI systems,” using different terms but with a similar scope. In contrast, the EU AI Act’s provisions on “high risk applications” relates primarily to the social layer, and those on transparency of foundation models pertain to the logical layer. Additionally, the Council of Europe’s Convention on AI focuses more on AI applications in the public sector. This clustering exercise is helpful to compare the initiatives based on their intended scope, whether their measures align with their stated objectives, and it allows international organizations to streamline their taxonomy.

Beyond taxonomy, the framework yields some observations on the challenges in global AI governance that lie ahead. For example, frontier AI companies are pushing to acquire the “means of production”—the energy and computing infrastructure of AI—so that the companies can operate the full “stack” of AI applications with minimal dependency on third parties. For instance, Microsoft announced in 2024 a deal to obtain nuclear energy to power its data centers, and Meta announced a similar deal in January 2026. Major cloud providers, including Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, host their own foundation models while developing leading applications. These actors can operate strategically across layers, and no single domestic or international organization can capture the full scope of their activity. In addition, we note significant strategic cross-layer collaborations, such as Nvidia and Google partnering on AI-optimized hardware, Google providing Anthropic with cloud infrastructure and TPU access, and AWS providing OpenAI with advanced AI training infrastructure and offering its customers access to OpenAI’s open-weight models through Amazon Bedrock. These alliances show that many AI applications at the social layer are built on a mix of infrastructure and logical components governed by different actors.

There’s also the emergence of cross-layer verticals. Take, for example, agents that combine logical-layer capabilities (planning, reasoning, tool execution) with social layer functions (autonomous actions within applications or workflows). Another vertical that cuts across layers is data, particularly the massive datasets used to train foundation models. While cloud data centers are typically associated with the infrastructure layer, the data that’s traditionally derived from activity in the social layer feeds back into models at the logical layer.

Zooming out further, general-purpose AI systems produce value at all layers, generating optimizations at the infrastructure, logical, and social levels, in a continuous, entangled AI loop. This again highlights how policies over activity in one layer can affect other layers. For example, rules about fairness in outcomes—a social layer function—may require changes to the datasets used to train models at the logical layer. A recent paper, led by OpenAI and co-authored by Yoshua Bengio, demonstrates how regulating AI compute at the infrastructure layer can create outcomes in other layers. The above examples suggest that, alongside the existing layers, some AI domains might be better understood as cross-layer verticals rather than neatly contained categories. Considering such verticals does not replace the three-layer framework but can complement it and help capture governance questions arising from increasingly integrated and embodied AI systems.

These trends pose significant governance challenges. One approach might be to seek a greater role for the United Nations, but that would likely raise some significant issues: first, because it is difficult to regulate fundamental AI questions with agility and without the risk of hindering innovation, as the EU AI Act drafting process demonstrated. The UN, with its bureaucracy and relatively slow decision-making processes, is ill-suited to tackle the highly dynamic nature of AI governance. Second, there is a risk that large-scale UN action would give undue weight to the interests of non-democratic states. Laura DeNardis and others have shown how non-democratic countries have sought to exert “control” over internet governance through UN bodies in which they hold more sway. The UN recently reaffirmed its commitment—albeit with some modifications—to an open, noncentralized model of internet governance, but the same battles for control over AI governance now risk being waged. In our view, rather than simply defaulting to UN-led governance, the challenge for international bodies of all types is to guard against the risks of mission creep and institutional overreach. Rather, the UN’s policymaking efforts should remain targeted, agile, and data-driven, with a view toward ensuring interoperability. Doing so would enable countries with similar values to address their most pressing issues and allow for future sharing of best practices and policy experience. In that sense, Pax Silica is timely and constitutes an appropriate restart of the global discussions.

Questions for Future Inquiry

For simplicity’s sake, we have proposed three broad layers to visualize the AI stack but concede that additional, more detailed layers could expand the model. For example, one could conceptualize foundation models as forming a separate layer, parallel to the physical infrastructure layer. Additionally, with the impending ubiquity of AI physical systems—such as autonomous vehicles; delivery drones; industrial, commercial, and private humanoid robots; smart cities; and AI-powered wearable devices—another layer could be added that’s parallel to the social layer. Finally, consistent with the AI Action Plan and Pax Silica’s reference to the full “AI stack,” a new layer could be added below the infrastructure layer to cover the materials and minerals essential to the AI stack. This includes silicon for semiconductor manufacturing and gallium-based compounds used in high-efficiency electronics to reduce energy loss in AI data centers. In addition, rare earth elements, such as dysprosium, are critical for enhancing high-performance permanent magnets used in data center cooling systems and advanced electric motors. Many of those key minerals are found in China or countries aligned with China, raising broader geopolitical concerns about supply chain sourcing.

Space-based data centers are another noteworthy development. For example, Nvidia’s Starcloud project aims to reduce land-based energy consumption. This could conceivably draw space governance into the AI governance conversation. Regulating the various actors across both the AI and space governance “layers” will likely pose new challenges and require adjustments to the three-layer framework.

The three-layer framework presented is intended to be descriptive. It identifies the actors and institutions that operate at each level, highlights where coordination might be appropriate, and prompts a nuanced approach to regulation. In that sense, the framework’s robustness can be tested: Does it accurately reflect the complex reality of the AI ecosystem? Yes, this proposed framework is merely a starting point, a way to organize what’s known today while leaving room for the questions, challenges, and policy choices that will shape the next generation of AI governance. No doubt, the framework should be refined and evolve to this reality. Thus, any change to the framework that enhances its robustness is welcome. To that end, we have created a public GitHub repository and invite readers to suggest further changes.

As noted above, the framework can also apply to the global governance of other major technologies. For instance, one could envision an infrastructure, logical, and social layer in quantum computing. Identifying the relevant actors in a quantum domain, and the organizations that “regulate” them, could be a fruitful exercise, particularly as the OECD undertakes groundbreaking work to develop recommendations for responsible stewardship of quantum technologies. In addition, advances in neurotechnologies and human-machine interfaces raise fascinating questions about the interplay between the hardware used for these technologies and the place of the human body as an even more fundamental “layer” in this ecosystem.

Ultimately, we, the authors, hope that applying the three-layer framework to AI governance and other fields of technological governance can help policymakers, academics, standard-making bodies, civil society organizations, and, of course, industry actors make sense of a fragmented and increasingly complex technology landscape. This, in turn, could contribute to a deeper, more sophisticated dialogue on the global policies that can unlock the potential benefits of these technologies.

.jpg?sfvrsn=319e4fa_3)

.jpg?sfvrsn=31790602_7)