Western Europeans Are Hedging on a Post-U.S. NATO

A recent survey of NATO’s four biggest members finds that Western Europe’s scramble to arm itself is riddled with contradictions.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

As NATO convenes its annual summit this week, Europe will be working hard to present a united front with the United States. Allies are building their military capabilities, and leaders such as British Prime Minister Keir Starmer and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz back U.S. strikes on Iran’s nuclear program, even as they caution against the risks of broader escalation. But underneath the surface, political divisions and America’s faltering commitment to Europe continue to fracture the alliance.

In some ways, the alliance will appear to be exactly what then-President Biden declared it to be at last year’s meeting: “stronger than it’s ever been in its history.” At least, materially. Following decades of sclerotic defense spending despite prodding by U.S. officials, governments in the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, and most other NATO members will arrive at The Hague with ambitious plans to modernize their armed forces. The alliance has even agreed to raise the defense spending target that it sets for its members from 2 to 5 percent of their gross domestic product—a sharp increase per the demand of President Trump.

Yet burgeoning defense budgets are only part of the story. All is not well within the 76-year-old alliance. NATO’s renewed appreciation for hard power owes less to Biden, the president who trumpeted the sanctity of America’s alliance commitments, than to Trump, the president who threatens to abandon them to contend with a revanchist Russia by themselves. Just as Russian President Vladimir Putin inadvertently strengthened the alliance’s resolve, so too has Trump.

For all its member countries’ investments in military budgets, NATO’s biggest vulnerabilities are political in nature. Trump’s second term has upended the alliance—in a jarring Oval Office meeting with Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy; in provocative speeches from the vice president; and in the administration’s willingness to take the Russian narrative of the war in Ukraine at face value. (Not to mention the threats against the United States’s northern neighbor, Canada, a NATO ally, and against Greenland, the territory of another NATO ally.) As it focuses more on Asia and America’s southern border than on Europe, the administration has considered downsizing its military presence on the continent and proved itself willing to exclude Europeans from discussions on their own security.

The transatlantic community is not just preparing for a future without a key pillar of its security. It’s also bracing itself for a world in which the United States is increasingly seen as an adversary, especially as Washington threatens tariffs, flirts with territorial expansion, and endorses far-right political parties that undermine European integration and collective security.

A recent survey conducted by my organization, the Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group, of NATO’s four biggest members—the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France—finds that, for all of these reasons, Western Europe’s scramble to arm itself is riddled with contradictions.

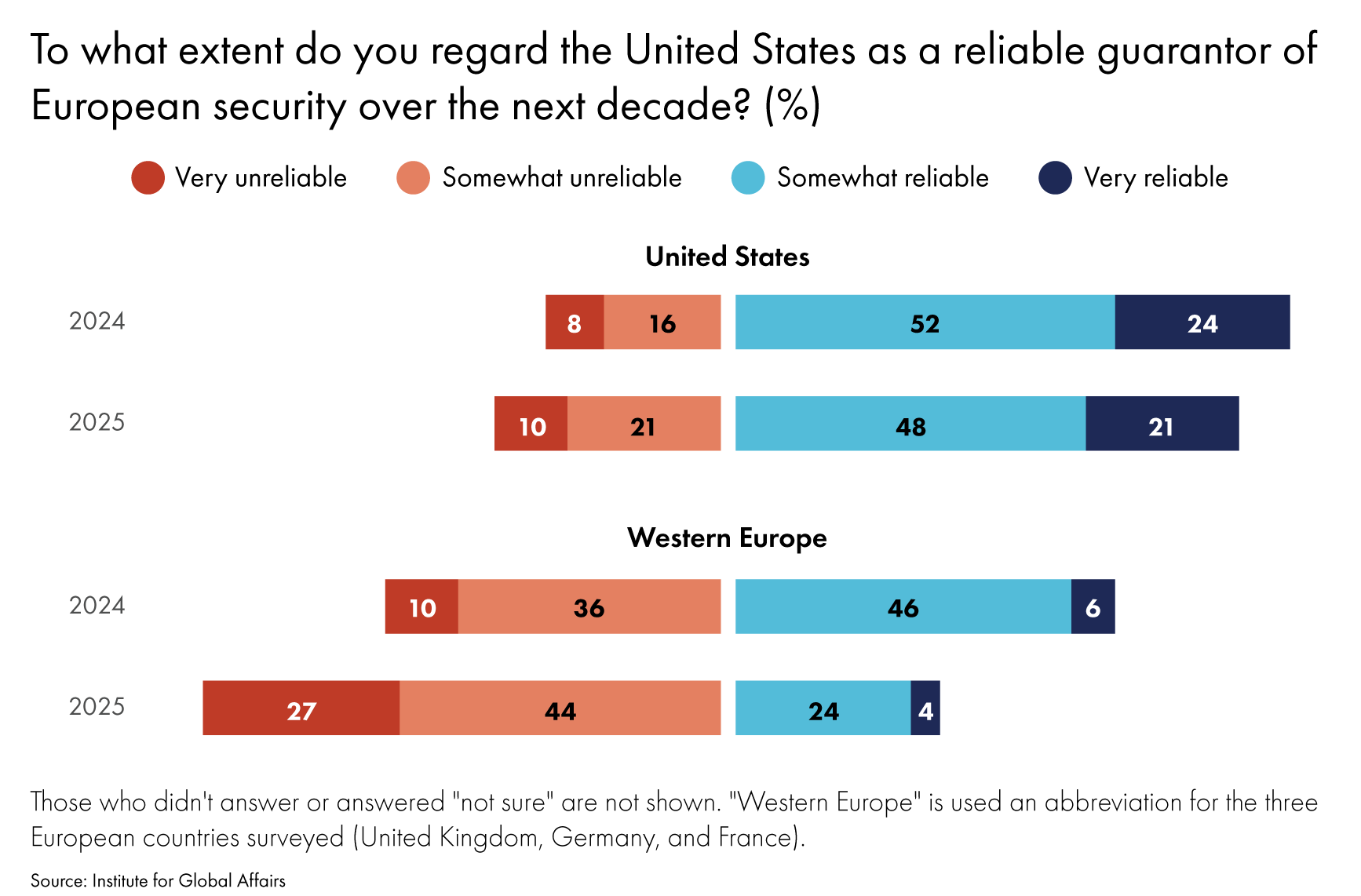

The majority of Western Europeans surveyed doubt America’s credibility. Fewer than one in 10 people in the U.K., Germany, and France are certain the United States would defend them if they were attacked, and fewer than half think it probably would. Across these three close allies, even fewer think the United States will be a reliable guarantor of European security over the next decade—down from 52 percent since last year, when we asked the same question.

Figure 1. Is it just Trump, or does NATO’s crisis of confidence run deeper? The United Kingdom, Germany, and France increasingly doubt America’s reliability to safeguard European security.

Source: Institute for Global Affairs

Questions about America’s willingness to defend its overseas allies have been a core pillar of the Atlantic alliance since its founding. However, concern is likely to grow more pronounced as the bulk of Washington’s attention shifts to regions of higher priority, and if crises at home and abroad continue to erode America’s strength.

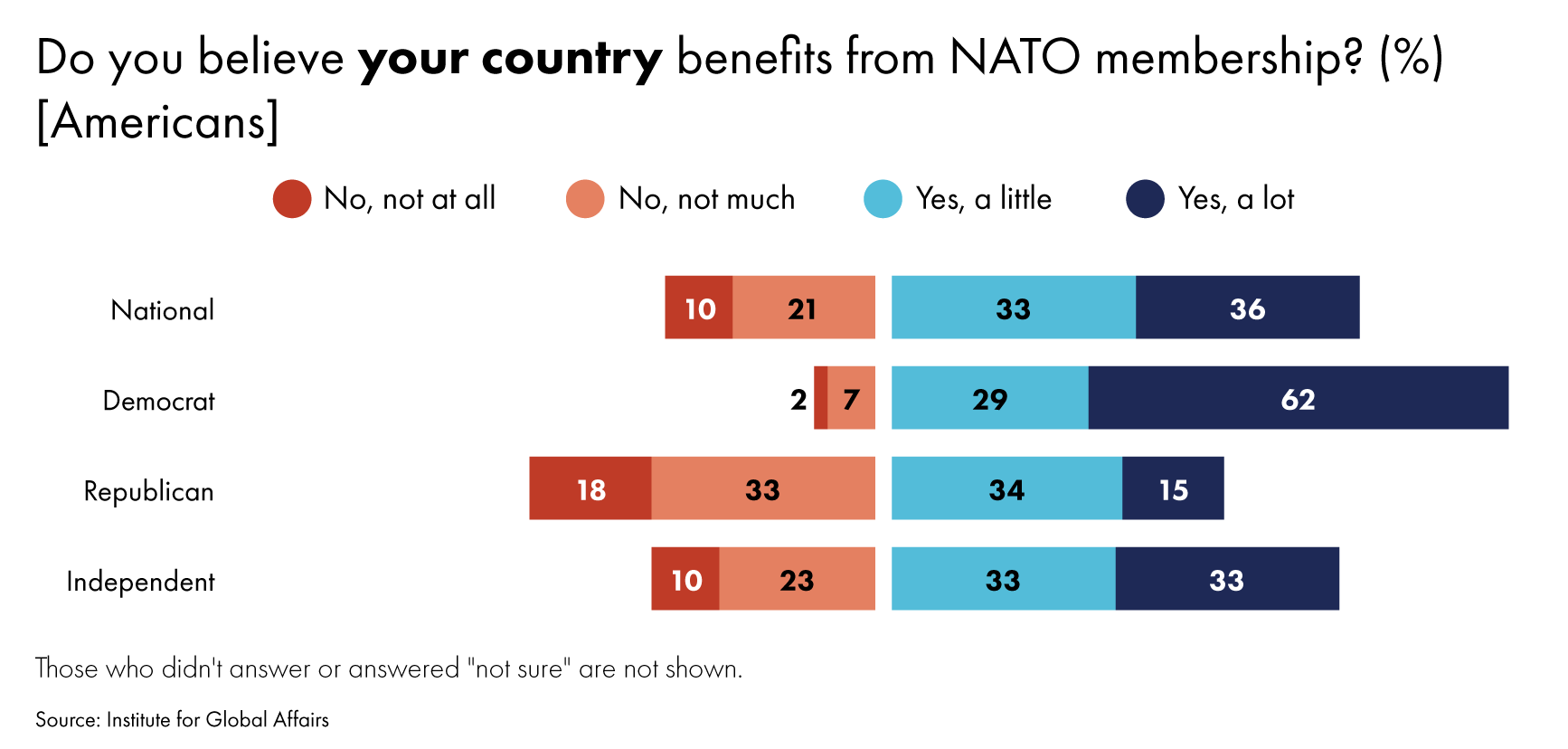

These factors have helped to transform transatlantic relations into a partisan issue. Our findings corroborate similar trends observed by other organizations, like the Pew Research Center, and echo criticisms shared by many Republican members of Congress: The alliance no longer enjoys bipartisan support and has become a faultline in MAGA foreign policy. Our survey finds that nearly all Democrats, but just shy of half of Republicans, think the U.S. benefits from NATO membership.

Figure 2. Politics doesn’t stop at the water’s edge. Republicans and Democrats disagree about the value NATO provides to the United States.

Source: Institute for Global Affairs

These findings add a sense of urgency to European officials’ calls to increase military spending and develop independent capabilities in the wake of Trump’s first term and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. At least for now, their constituents appear generally receptive. Slight majorities in each surveyed country say they support Europe developing its own army, and across Western Europe, many think their countries could be spending more on defense. In the U.K., which targets a return to Cold War-level spending, more than four and a half times as many people surveyed want to boost, rather than cut, defense spending. And, in Germany, which had promised a “new beginning” in its defense and foreign policy to reverse decades of underinvestment in its military—and has since pledged to hit NATO’s new 5 percent benchmark––more than three times as many people want to spend more, not less, on the military.

Europe’s move toward strategic autonomy need not mean the demise of collective defense: Most respondents view the U.S. as a necessary partner or an ally—a finding that mirrors that of a poll conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations shortly before Trump’s inauguration—and sizable majorities think it’s time for Europe to take more responsibility for it defense while also preserving the NATO alliance with the United States.

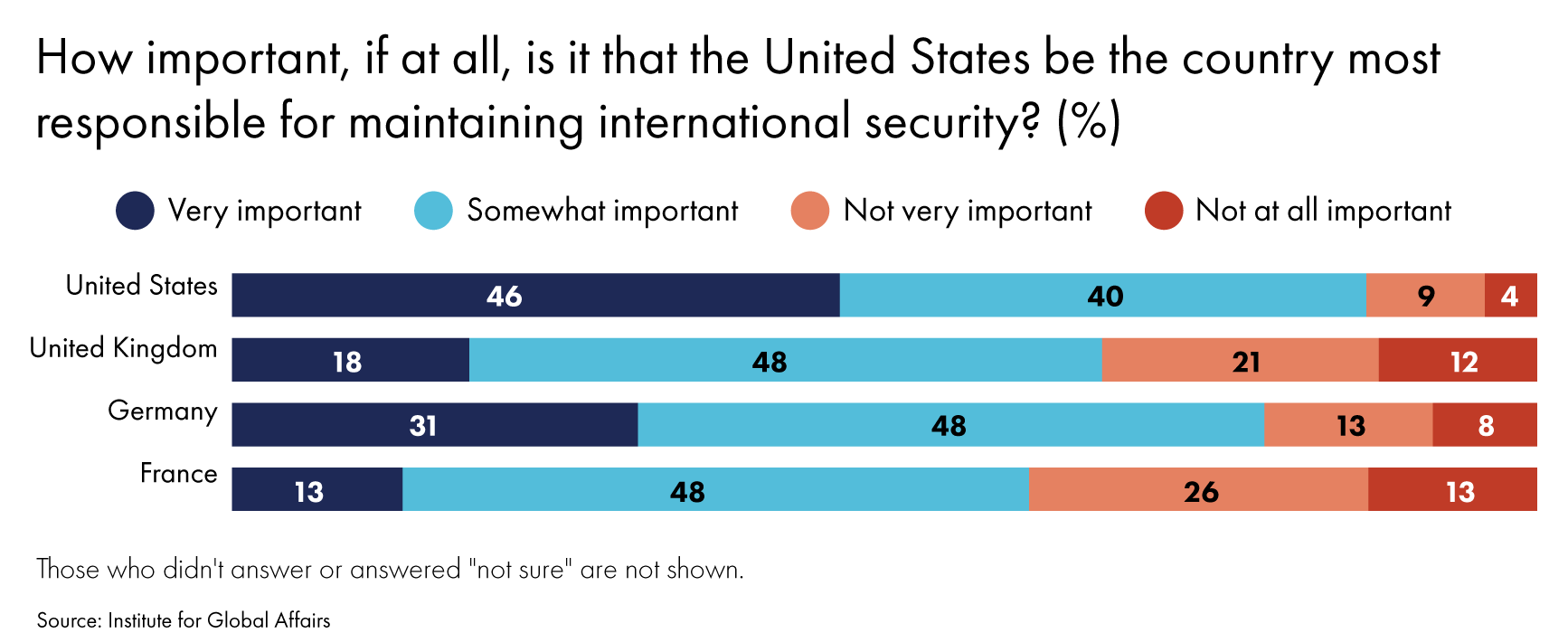

European planners are hard-pressed to stave off a complete rupture in transatlantic ties, and even as they try to make up for lost time, they have yet to fully reckon with a future without the United States. In some ways, Western Europe still views the United States to be a singular force in global affairs. Respondents cite America’s military muscle and the strength of the U.S. as the sources of its power, and many think it important for the United States to be most responsible for maintaining international security.

Figure 3. Still the indispensable nation? America’s reliability is in question, yet most British, Germans, and French think it’s important for the United States to be most responsible for keeping order in the world.

Source: Institute for Global Affairs

Europe’s rush to arms faces plenty of other challenges: Europe’s joint-defense initiatives and industrial base are not yet ready; it remains dependent on U.S. capabilities, from the software used in weapons systems to the aircraft needed to transport troops; and the United States continues to expect Europeans to equip themselves with American-made weapons. Europe also risks taking for granted the politics within its borders. The loss of America’s security umbrella, if not properly managed, could resurface simmering ethnic tensions and historical grievances long kept at bay.

Public opinion can be fickle. Support for Europe’s drive to become more self-sufficient may wane, especially as defense spending competes with the social welfare programs to which West Europeans have become accustomed. Rolling back social programs would be a significant departure from the social contract that has brought much prosperity and stability to Western Europe.

Still, the shock prompted by Donald Trump’s election, and the uncertainty it caused, may have been just the long-overdue kick the alliance needs to get its house in order.

.jpg?sfvrsn=97d38316_5)