What’s Behind the Spike of Violence in El Salvador?

The country’s criminal groups have learned to play the politics of violence.

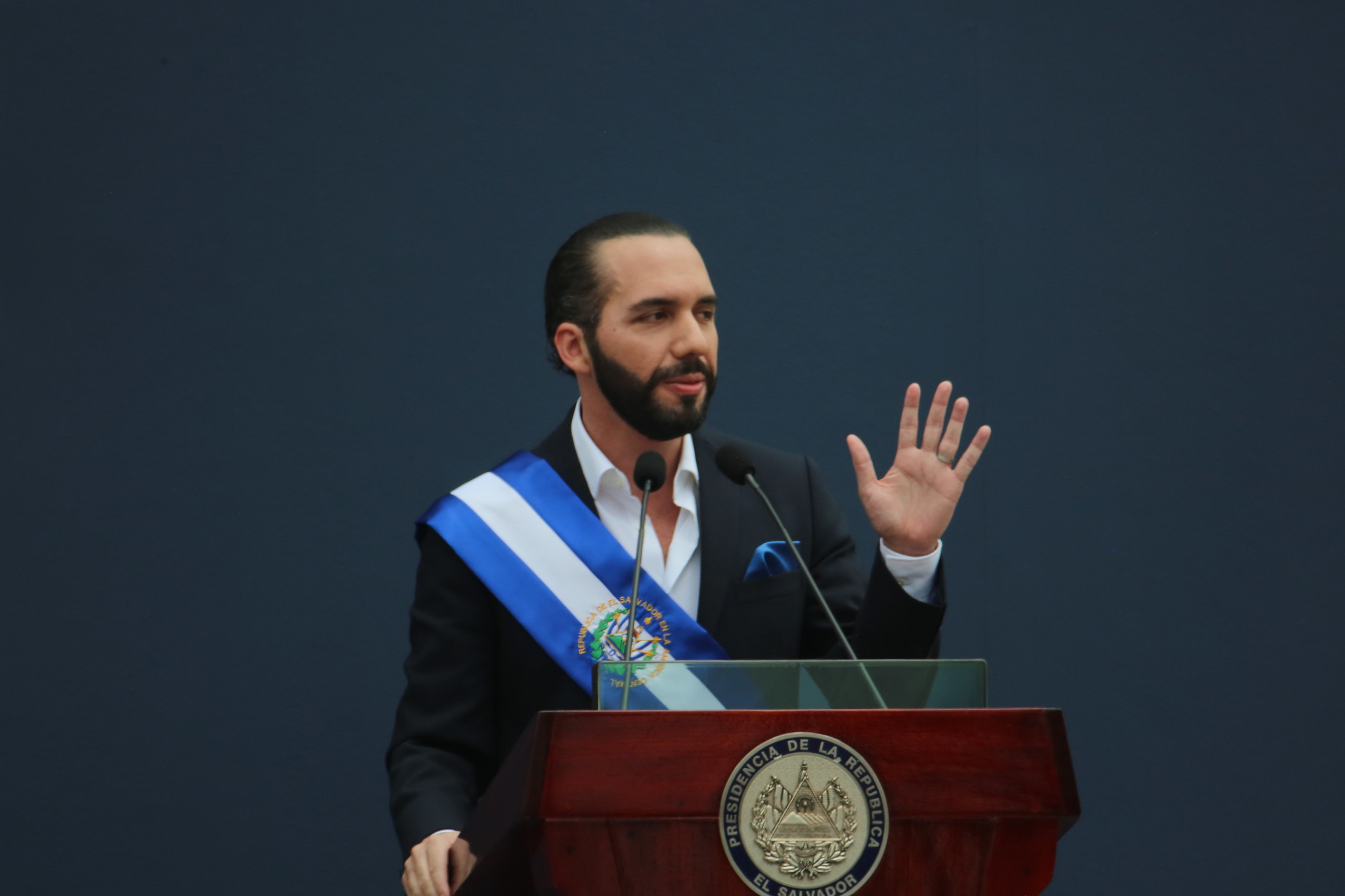

El Salvador was once widely considered the “homicide capital of the world.” But over the past seven years, the country’s murder rate—which peaked at over 105 homicides per 100,000 people in 2015—has plummeted. Since Nayib Bukele became president in 2019, the number of homicides has halved. And in the first two months of 2022, the country achieved a major milestone: it recorded four days without a single reported killing.

But late last month, in the space of 72 hours, violence returned to El Salvador with a vengeance. Between March 25 and March 27, no fewer than 87 Salvadorans were murdered. According to El Faro, most of the victims had no known connection to the maras, El Salvador’s deadly street gangs. Victims included a 42-year-old domestic worker, a 27-year-old surfing instructor, a 40-year-old shopkeeper and a 22-year-old shoemaker. The oldest victim was 66. The youngest was 18. Some of their bodies were abandoned on the side of the road for the authorities—and the cameras—to find. March 26, when most of the violence was carried out, marked El Salvador’s “most violent day of the century” so far.

By the morning of Sunday, March 27, Bukele and his legislative allies had declared a national state of emergency, curtailing many constitutional rights—including freedom of assembly, access to legal counsel and other basic due process guarantees. The police and the military intensified their presence on the ground and conducted more than 8,000 arrests. Local and international observers quickly warned of the potential for widespread human rights abuses. Bukele and his allies responded by doubling down on the crackdown, most notably by hardening mandatory minimums for gang-related crimes,loosening due process guarantees for suspected gang members, and threatening to jail journalists who spread gang messages. To borrow Bukele’s latest hashtag, the Salvadoran government is now in an all-out #GuerraContraPandillas, or war against the street gangs.

How did El Salvador reach this point? The Salvadoran street gangs have learned to use violence as political leverage over elected governments. The ruthless events of March 25-27 are an attempt—primarily by one gang, the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13—to exercise that leverage in the context of a secretive non-aggression pact brokered by the Bukele administration. How things unfold going forward may hinge on what the Salvadoran government—and the international community—choose to do next.

How the Gangs Learned to Play the Politics of Violence

Most criminal organizations use violence to settle disputes, fight rivals, and enforce business deals. Traditionally, the Salvadoran street gangs have been no different. Violence is driven primarily by clashes between major street gangs and by confrontations between the gangs and law enforcement. Gangs also use violence to extract “protection taxes” from communities under their control: by one estimate, for example, the Salvadoran gangs extort around 70 percent of the country’s businesses.

In early 2012, the Salvadoran government—then led by President Mauricio Funes—negotiated a pact with El Salvador’s two major street gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18. Negotiating from behind bars, gang leaders agreed to an unprecedented ceasefire. In exchange, they asked the government to scale back repressive policing tactics, provide better prison conditions and invest in rehabilitation programs for former inmates.

The pact worked. According to official data, homicides plummeted by almost 60 percent immediately after the agreement went into effect. At that year’s Summit of the Americas—a meeting of the hemisphere’s heads of state—Funes boasted: “Yesterday, after years when the homicide rate reached alarming levels of up to 18 per day, we did not have a single assassination in our entire country.”

But even as violence declined, the 2012 pact had dire—and much longer-lasting—unintended consequences: it taught the street gangs how to turn their ability to kill into political influence. In El Salvador, elections can be won and lost on the issue of crime alone: In 2012, 49 percent of Salvadorans said security was the most important problem faced by their country; by 2018, that number had risen to 62 percent. During the 2012 pact, the gangs discovered how much elected leaders were willing to risk in order to drive down homicide rates. Gang leaders also learned how to work with their criminal rivals to maximize their leverage over politicians—and, crucially, that they could control homicide rates and enforce agreements even from behind bars.

By late 2013, the pact had begun to fray. Violence started to climb, in part because the gangs were settling scores they had accumulated during the ceasefire and in part because they were attempting to bring the government back to the negotiation table. In April 2014, Funes publicly accused the Barrio 18 gang of breaking the agreement. By 2015, the homicide rate skyrocketed to 105 per 100,000—up from 70 per 100,000 before the truce and from 40 per 100,000 during the ceasefire. In 2016, the legislature outlawed gang negotiations and the attorney general ordered the arrest of 21 individuals who had helped broker the 2012 truce. No longer in office, Funes fled to Nicaragua to avoid capture. His successor, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, said the government would not reenter negotiations with the gangs.

The pact unraveled. But the gangs had learned how to manipulate homicide rates in order to extract concessions from elected governments. In the words of Juan Martínez D’Aubuisson, a leading expert in Salvadoran gangs, “since 2012, the gangs and the state communicate through deaths.”

The Bukele Pact

Nayib Bukele succeeded Sánchez Cerén as President in June 2019. Bukele’s distinct blend of populism, authoritarianism, and social media savvy—which I have dubbed millennial authoritarianism—helped the 40-year-old capitalize on public dissatisfaction with the political establishment, upending El Salvador’s long-standing party system in the process. Since May 2021, Bukele’s party has held a supermajority in the national legislature. During Bukele’s term, homicides have declined from about 36 to 18 per 100,000 people.

Publicly, Bukele attributes this decline in homicides to the Territorial Control Plan, his flagship anti-crime policy. In broad terms, the Plan involves modernizing El Salvador’s security forces and increasing their presence across the country’s territory, with a focus on gang strongholds. But behind the scenes, Bukele’s government has struck a non-aggression pact that bears a striking resemblance to the 2012 agreement.

Details of the Bukele pact (which the government has repeatedly denied) are elusive, but its broad contours have been uncovered by the investigative news outlet El Faro. By October 2019—four months after Bukele was sworn in—government representatives were engaged in extensive negotiations with the leaders of MS-13 and Barrio 18. Bukele’s emissaries asked the gangs to cut homicides and to help Nuevas Ideas, Bukele’s political party, mobilize votes in the 2021 midterm elections. In exchange, the Bukele administration offered to improve prison conditions, amend harsh anti-crime laws and resist U.S. calls to extradite gang leaders.

Tellingly, the trove of official documents examined by El Faro suggests that setbacks in the negotiations were consistently followed by homicide spikes. The first such episode came in April 2020, when the MS-13 went on a five-day killing spree that left over 80 dead. In November 2021, the gangs struck again, killing 46. In both cases, a majority of victims had no known affiliation with the gangs and “the murders stopped as quickly as they started.” And in each instance, the government responded by temporarily cracking down on the gangs, both in and out of prisons.

These isolated, fleeting killing sprees are not consistent with an all-out war for territorial control between criminal groups and the state. Nor are they consistent with rival gangs waging war against each other. Instead, they are deliberate efforts from gangs to steer negotiations with the government in their favor. They are a clear reminder to Bukele—who has strived to spread his vision of El Salvador as an increasingly blissful, forward-looking country—that the gangs can unleash immense violence just as easily as they can withhold it. The gangs are, so to speak, banging their fists on the negotiating table.

The events of March 25-27 are yet another “message written in blood.” In the words of a police union spokesperson who talked to El Faro following the bloodshed: “The gangs are sending a forceful message: They are in charge. They are saying that they can increase or decrease homicides when they see fit.”

What exactly triggered this latest salvo? Because negotiations between the gangs and the Bukele administration are secretive, it is difficult to know for certain. One hypothesis is that the killings were a preemptive move by the gangs, spurred by rising tensions between El Salvador and the United States over the possible extradition of several gang leaders. But there are other possible explanations. Before the 2021 midterm elections, the Bukele government reportedly offered to repeal a set of anti-crime laws if the gangs helped the president’s party gain control of the legislature; as the Nuevas Ideas supermajority nears its first anniversary in office, the gangs may now be pressuring Bukele to keep his side of the deal. Or, if recent reports that several high-profile gang leaders have been quietly released from prison are true, these leaders may now be attempting to broaden the scope of the pact—which has so far delivered benefits mainly to gang members who are behind bars.

We can only speculate. What is clear is that this recent string of killings must be understood as a violent bargaining tactic in the context of the Bukele administration’s ongoing negotiations with the criminal groups.

What Will Bukele Do Next?

The attacks of April 2020 and November 2021 were followed by harsh government reprisals. On both occasions, having delivered their message, the gangs did not fight back and, before long, negotiations resumed. The most recent attacks—and the government’s response—have been larger in scale. But, once again, the gangs show little indication of fighting back. As before, negotiations may soon resume.

But is it possible that the gangs have overplayed their hand? The March 2022 attacks were deadlier and gained much more domestic and international attention than previous killing sprees. Similarly, Bukele has gone much further than before to punish these attacks. After the November 2021 killings, for example, the government reportedly arrested 1,831 gang members; in the aftermath of last month’s killings, it has conducted at least four times as many arrests. Bukele may decide that negotiations are no longer politically viable. From this point forward, he may choose repression and direct confrontation.

How likely is Bukele to return to the negotiating table? The answer may ultimately come down to electoral incentives. The Constitutional Court—which Bukele and his allies packed last year—has paved the way for him to seek reelection in 2024. At face value, repressive anti-crime policies tend to be popular with voters. But, as criminal groups fight back, confrontation between criminals and the state tends to trigger high levels of violence in the medium and long term. Violence, in turn, tends to hurt incumbents. As he prepares to launch his reelection bid, Bukele may determine that sporadic outbursts of violence are less costly, electorally, than consistently high homicide rates. Bukele may thus decide to quietly return to the negotiating table.

This logic assumes that the 2024 presidential elections will be free and fair. During his three years in power, Bukele has systematically eliminated checks and balances, attacked political opponents, and undermined the free press. In a 2021 speech, he vowed never to let his enemies return to power:

For 200 years, democracy was a pantomime. It was all theater. We had elections, yes, but when politicians got to power, they forgot about the people. … They never cared about people, they only cared about votes. To them I say: keep crying for that system in which you saw our country as your plantation and our people as your laborers, keep tearing your hair out because you can no longer enrich yourself at the expense of the Salvadoran people. ... We will never again return to the system that for two centuries sank us into crime, into corruption, into inequality, and into poverty. Never again. Don’t get any ideas. As long as God gives me strength, I will not allow it.

To the extent that the 2024 elections are free and fair—that is, to the extent that Bukele has to compete for votes on equal footing with other candidates—the government will face increasing incentives to return to the negotiation table in order to keep homicides rates down. On the other hand, if the elections serve only to rubber stamp a second Bukele term, the president may be able to sustain a prolonged strategy of confrontation with the gangs.

The Role of the International Community Moving Forward

How things unfold in El Salvador will be determined primarily by Bukele—and the street gangs’—next moves. But the international community, and the United States in particular, have important roles to play.

First, the international community can continue to document abuses of state power in El Salvador. Immediately after the government declared its state of emergency on March 27, international watchdogs began to warn of possible human rights violations. For example, representatives of the Washington Office in Latin America and the Due Process of Law Foundation noted that the state of emergency

effectively suspended some human rights, such as the right to a defense, knowing the charges against you, the right not to incriminate yourself and having access to a lawyer. The decree also suspended the right to freedom of assembly and association and allows the government to intercept private communications without a court order.

Referring to Bukele’s announcement that he would harden prison conditions in order to send a message to the gangs, Human Rights Watch added:

Punishing detainees for the actions of people outside prison is a form of collective punishment that violates multiple human rights, and the harsh treatment of detainees described by Bukele may amount to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment … Depriving detainees of adequate clothing, light, bedding, access to the outdoors, food, and water is also inconsistent with international standards on the treatment of detainees.

Over the past year, the United States government has also brought attention to Bukele’s gang negotiations and published lists of officials involved in corrupt and undemocratic activities—including, but not limited to, negotiating with criminals. Bukele is quick to dismiss (and sometimes mock) such statements. But he does so precisely because these international actors provide an invaluable source of accountability —especially at a time when Bukele is undermining domestic checks and balances.

Second, the international community, and the United States especially, can adjust its treatment of Salvadoran immigrants to be more in line with reality. Many Salvadoran immigrants flee their country in order to escape the consequences of gang violence; once in the United States, these immigrants’ asylum claims then hinge on whether they can demonstrate that they are indeed fleeing unsafe conditions. In recent months, I have spoken to several refugee advocates who report a clear pattern: because Salvadoran homicide rates are declining, US immigration judges believe El Salvador is getting safer and are increasingly unlikely to grant asylum claims. The events of March 25-27 show that this view oversimplifies circumstances on the ground. Under the Bukele pact, violence may have simply become more unpredictable. And, if Bukele shifts toward a permanent strategy of confrontation and repression, Salvadorans may face increasing violence from gangs and from the state.

Additionally, the United States could pay closer attention to how its own efforts to combat organized crime reverberate in El Salvador. For ten years, the United States has classified MS-13 as a transnational criminal organization. Most recently, it has pressured the Bukele administration to extradite several gang leaders; in December 2020, a grand jury in New York indicted one of these gang leaders on transnational narcoterrorism charges. For better or worse, such actions have the potential to undermine delicate negotiations between gangs and the government—possibly at a great human cost to regular Salvadorans.

Finally, the international community can redouble its efforts to support pro-democracy advocates in El Salvador. In May 2021, after Bukele and his allies packed the Supreme Court, the United States redirected some of its assistance away from government institutions and toward civil society groups. Especially as Bukele works to undermine these groups, continued international support could help shore up El Salvador’s democracy and limit abuses of state power.

-1928c983-394b-444d-b1ec-f6590b7d9fee.jpeg?sfvrsn=78498e1e_7)

.jpeg?sfvrsn=773924a2_5)