Where the Fake Electors Cases Stand in State Court

The criminal cases against Donald Trump over his efforts to steal the 2020 election have not had an easy time of it. In federal court, Special Counsel Jack Smith’s prosecution was set back on its heels following the Supreme Court’s ruling finding broad presidential immunity for official acts—though Smith is doing his best to push forward. In Fulton County, Georgia, the case brought against Trump by District Attorney Fani Willis has run aground on a bizarre scandal over an alleged conflict of interest related to Willis’s romantic life.

But these prosecutions of Trump are not the only efforts to seek accountability for the 2020 election in criminal court. After all, the former president did not act alone. In addition to the Georgia case, prosecutors in four other states have pursued charges against individuals involved in the Trump campaign’s scheme to submit duplicate electoral certificates claiming that Trump had won those states. Some of those prosecutions are still moving forward, but others have faced potentially fatal complications. In no instance have these cases moved forward with perfect speed or smoothness.

In April, we reviewed the status of state-level investigations and prosecutions of what’s come to be known colloquially as the “fake electors scheme.” Here, we provide an overview of what’s happened in the intervening months. Since last spring, the Georgia case ground largely to a halt, a Nevada judge dismissed the prosecution of fake electors in that state, and pretrial proceedings have moved forward in Michigan. Meanwhile, the attorneys general of Arizona and Wisconsin have announced indictments of their own.

What follows is an in-depth, in-the-weeds status update of those cases, which we summarize briefly in this chart:

Eagle-eyed readers will note that this overview leaves out Pennsylvania and New Mexico, the other two states where Trump electors submitted fake electoral certificates in 2020. There’s a reason for that. As we wrote in April, the fake electoral certificates drafted in the Keystone State and the Land of Enchantment—unlike in other states—included crucial wording indicating that the certificates were to be used only if Trump was determined to have won the state. The attorneys general of both Pennsylvania and New Mexico separately determined that this language precluded criminal charges for the electors in their states, though both made their displeasure with the scheme clear. “Though their rhetoric and policy were intentionally misleading and purposefully damaging to our democracy … our office does not believe this meets the legal standards for forgery,” said then-Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro (now the state’s governor) of the fake electors in 2022.

There’s a good reason these prosecutions have largely fallen off the national radar: It’s hard to keep track of state court proceedings moving forward in five different jurisdictions. These cases are complicated, slow, and technical, with a great deal of variability between both the facts of the cases and the mechanics of state law. What’s more, state court documents are not always easily accessible. To research and report this piece, we examined trial and appellate dockets, watched live streams of state court hearings, and read through press reports. We’re indebted to the local journalists—at outlets like the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the Detroit Free Press, the Nevada Independent, and others—who have covered these cases closely.

Georgia

The Georgia indictment, handed up in August 2023, is by far the most sprawling of the state-level prosecutions—addressing not just the fake electors scheme but also the pressuring of Georgia state officials to upend the state’s electoral count, the harassment of state election workers, and an apparent breach of voting systems in Coffee County. It’s also the only case to feature charges against the former president himself. Still, the effort to create faux electoral certificates features prominently in the charges. Among the 18 co-defendants charged in the original indictment were three of the Georgia fake electors, Cathleen Alston Latham, David Shafer, and Shawn Still, all three of whom, like Trump, have pleaded not guilty.

Over the past six months, the case ran aground in a bizarre scandal over Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis’s personal relationship with Special Prosecutor Nathan Wade, which Lawfare’s Anna Bower has covered in depth. In January 2024, one of the defendants, Trump campaign aide Michael Roman, filed a motion to dismiss the indictment on the grounds that an alleged romantic relationship between Willis and Wade created a conflict of interest for Willis and mandated her disqualification from prosecuting the case. Eight co-defendants—including Trump, as well as Latham and Shafer—joined Roman’s motion. In March, Fulton County District Judge Scott McAfee found that Willis was not disqualified. The Georgia Court of Appeals agreed to hear the defendants’ appeal of McAfee’s ruling and in July placed the prosecution of those nine defendants on hold while the appeal remains pending. (Another defendant who did not join in the motion, Misty Hampton, was granted a stay as well.) Oral argument is currently scheduled for Dec. 5.

The case has faced other hiccups. In a March ruling, Judge McAfee tossed out six counts relating to Trump’s pressure campaign against state officials. Willis has appealed the ruling.

This September, the judge dismissed three more counts, including two related directly to the fake electors effort—this time on Supremacy Clause grounds. A group of co-defendants had argued that the Electoral Count Act, the federal law that establishes the election certification process, preempts the use of Georgia state law to prosecute the electors scheme. Judge McAfee rejected this argument. But he held that three counts charged under Official Code of Georgia Annotated (OCGA) § 16-10-20.1—each related to filing false documents before a federal court—were prohibited under In re Loney, which McAfee described as preserving “the federal court’s ability to police its own proceedings.” One of the counts in question involved a false claim of voter fraud made by Trump in his federal litigation seeking to decertify Georgia’s election results; the other two concerned the mailing of the fake electoral certificates to federal court. Currently, McAfee’s ruling applies only to Trump attorney John Eastman and Still, the only two defendants charged under these counts for whom the case is not stayed.

At least one other major development has taken place while the case is stayed, concerning another fake elector whose legal fate remained unsettled. As of September, Georgia Lt. Gov. Burt Jones will not face criminal charges despite having signed the fake electoral certificate.

The lieutenant governor—a state senator during the 2020 election—had been under investigation by Willis’s office, but a state judge disqualified Willis from investigating Jones after her involvement in a fundraiser for Jones’s opponent during his 2022 campaign for the lieutenant governor position. The decision of how to handle the Jones investigation fell to Georgia’s nonpartisan Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council—the executive director of which, Pete Skandalakis, appointed himself as a special prosecutor to look into Jones. In September, Skandalakis announced his finding that Jones’s conduct did not merit further investigation and that Jones had “acted in a manner consistent with his position representing the concerns of his constituents and in reliance upon the advice of attorneys when he served as an alternate elector.”

Between Latham, Shafer, Still, and Jones, only four out of Georgia’s 16 fake electors are accounted for—although at one point, Willis indicated that all 16 were potential targets of the investigation. Reportedly, at least eight fake electors reached immunity deals with Willis’s office in the course of her probe. Beyond this, the math becomes uncertain.

On Oct. 24, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit rejected an effort by Latham, Shafer, and Still to remove their case to federal court on the grounds that the three were performing a federal function by acting as “contingent” electors. In a concurring opinion, Judge Robin Rosenbaum wrote that the three “were no more presidential Electors simply because they give themselves the title than Martin Sheen was ever the President because he went by President Bartlet” in the television show “The West Wing.” The decision followed the appeals court’s previous rejection of Trump’s former chief of staff Mark Meadows’s request to remove his own Georgia prosecution to federal court—which Meadows is now petitioning the Supreme Court to review—and was issued alongside yet another ruling denying a similar motion to remove by former Justice Department official and Fulton County co-defendant Jeffrey Clark.

Michigan

In July 2023, Attorney General Dana Nessel announced felony charges against the 16 Michigan residents who had signed their names to the 2020 electoral certificates for Trump, alleging the defendants had falsely claimed to be official electors. Each defendant was charged with a range of conspiracy and forgery counts.

Over a year later, the case remains in pretrial proceedings. One fake elector (James Renner) reportedly entered into a cooperation deal with the attorney general. Other fake electors (Clifford Frost and Mari-Ann Henry) filed motions to dismiss, claiming that the attorney general could not prove the necessary intent required for all eight charges. Frost and Henry supported their motions to dismiss by arguing that Attorney General Nessel did not believe the two defendants intended to unlawfully interfere in Michigan’s electoral process, because of comments made at a Sept. 18, 2023, event: “[Fake electors] are people who have been brainwashed” and “legit believe” that former President Trump won the 2020 election. Ingham County 54A District Judge Kristen Simmons rejected the motions; after Frost failed to secure an injunction from federal district court to pause the state court proceedings, he appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, which has yet to issue a decision following Frost’s reply brief on July 19. Other than Renner, the fake electors pleaded not guilty, triggering a preliminary hearing to determine bind over—that is, whether there is sufficient evidence to send the cases to a jury trial.

Judge Simmons has presided over the preliminary hearings. The first round of hearings, including Kathy Berden, Amy Facchinello, Clifford Frost, Mari-Ann Henry, Michele Lundgren, and Meshawn Maddock, concluded in April 2024. The second round, including William Choate, Clifford Frost, Mayra Rodriquez, Rose Rook, Marian Sheridan, and Ken Thompson, concluded in June. The remaining three fake electors, including Wyoming, Michigan, Mayor Kent Vanderwood, Stanley Grot, and Timothy King, completed their preliminary hearings on Oct. 7. Simmons remarked that she would likely not issue her decisions until all preliminary exams are completed.

At the preliminary hearings, state prosecutors argued that the fake electors knowingly attempted to defraud Michigan voters by trying to cast Michigan’s electoral votes for Trump, even though there was no evidence of voter fraud. The State of Michigan also relied on its key witness, Special Agent Howard Shock, who completed the affidavits used to charge the fake electors. It seems, however, that Shock was not an ideal witness for the government. When questioned by defense attorneys on cross-examination, he apparently had trouble recalling specific details of his investigation. According to reporting on the hearing, Simmons ordered recesses to allow Shock to refresh his recollection, which included reviewing information—such as registration data—to link defendants to key evidence that supported search warrants. This type of aid is permissible under Rule 612 of the Michigan Rules of Evidence—and of the Federal Rules of Evidence—and allows witnesses to remind themselves of information they once knew by referencing written or other materials. Nonetheless, testimony that relies heavily on this tool can seem to undermine the witness’s credibility. Shock’s performance prompted Judge Simmons to remark this was not a “great presentation” for the government’s case. Further, Simmons noted, “I think it’s glaring that we have a concern in this courtroom about the investigation and his ability to put forth information from that investigation.”

Arguing that prosecutors lacked sufficient evidence to move the case to jury trial, defense counsel for all of the fake electors suggested that the electors’ conduct was lawful, because they were preparing to certify the election in the event that Michigan’s election results were “flipped” from Biden to Trump. Additionally, defense counsel argued that the Trump campaign and its attorneys misrepresented the legality of an alternative election certification process, tricking the electors into believing that their actions were within legal bounds. As such, they argued, the electors lacked the requisite mens rea.

Perhaps the biggest news from the preliminary hearings was when Shock, in response to questioning from defense counsel, revealed the identities of a range of individuals whom the attorney general’s office considered to be unindicted co-conspirators, including Rudy Giuliani, Jenna Ellis, Mark Meadows—and, most notably, former President Trump himself. Among the other unindicted co-conspirators, according to Shock, were Trump attorney Kenneth Chesebro, Trump campaign worker Chris Velasco, the state’s former Republican Party Chair Laura Cox, former Republican Michigan House Speaker Tom Leonard and his wife Jenell Leonard, and Republican consultant Stu Sandler.

It’s unclear when Judge Simmons might rule on whether there is enough evidence to send the fake electors to a jury trial. For the prosecutors to prevail, they will need to convince Simmons (and not a jury) that there is probable cause to maintain the state’s criminal charges against the fake electors. If and when the fake electors’ cases are sent to a jury trial, the standard of evidence will become the traditional criminal trial standard of beyond a reasonable doubt.

Nevada

The State of Nevada’s criminal case against six fake electors has been complicated from the outset. In May 2023, Attorney General Aaron Ford announced that state laws did not cover the fake elector scheme. Soon thereafter, Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo vetoed pending legislation that would have criminalized fake elector schemes in the future. Four months later, Ford appeared to change his approach, telling a reporter that he had “never said that we’re not going to prosecute.”

A Las Vegas grand jury indicted the fake electors in December 2023 on charges of offering a false instrument for filing and uttering a forged instrument, carrying a possible sentence of one to five years of incarceration. In response, the defendants each filed petitions for a writ of habeas corpus, claiming that Nevada failed to establish probable cause and provide exculpatory evidence. Defendant Eileen Rice also filed a motion to dismiss the case for improper venue, arguing that the alleged actions by the fake electors lacked a sufficient connection to Clark County, where Las Vegas is located.

Rice argued that the fake electors met to conduct the signing ceremony of the electoral certificate elsewhere in the state, in Carson City—and the faux certificates were mailed out from Douglas County. Though the return address on the envelopes was within Clark County, and one of the copies was mailed to an address in Las Vegas, Rice took the view that this was not sufficient to establish venue. In response, the attorney general’s office pointed to evidence that two of the defendants had been located in Clark County when drafting and revising the language for the electoral certificate. “[T]he State has alleged these crimes were committed as a conspiracy,” prosecutors wrote in their opposition to Rice’s motion to dismiss, “and venue is proper wherever some portions of the conspiracy occurred.”

Richard Wright, who represents defendant Michael McDonald, has framed the dispute over venue in political terms, suggesting in an early interview to the Nevada Independent that prosecutors brought charges in Clark County “because it’s Democratic,” while Carson City and Douglas County are in “a Republican area.” During a hearing on the motion to dismiss in June, Wright made a similar intimation: “I think everyone in this courtroom knows why it’s in Clark County.”

On June 21, Clark County District Court Judge Mary Kay Holthus granted the motion to dismiss from the bench, issuing a brisk six-page order the following month. (Readers may recall when Judge Holthus briefly grabbed national headlines in January after an aggrieved defendant charged the bench and attacked her during a sentencing hearing.) While venue can be proper when a crime is not committed in a county, Holthus pointed to Nevada’s Second Judicial District Court holding in Guzman v. Second Judicial District Court, which states: “In Nevada, venue cannot be based on supposedly preparatory acts unless the evidence shows that those acts were undertaken with the intent to commit the charged crime and in furtherance of that crime.” In Holthus’s view, the State of Nevada failed to meet its burden (by a preponderance of the evidence), because it failed to establish that either the defendants’ formation of intent or their preparatory acts occurred in Clark Country. The judge focused on “a supplement listing all evidence of Clark County contacts” submitted by the state, ultimately concluding that this list amounted to “speculative and insufficient” evidence that preparatory acts were committed with intent in Clark County.” While Holthus did not endorse a particular venue that would be sufficient under this test, her opinion mentions both Douglas County and Carson City as locations where there is both the required preparatory act and intent.

Following Holthus’s dismissal, the status of Nevada’s criminal charges against the fake electors is unclear. The attorney general quickly appealed and filed a motion with the Nevada Supreme Court, requesting an expedited consideration. No hearing date is currently scheduled.

If the attorney general’s appeal is denied, then the list of possible crimes with which to charge defendants, even after refiling in Douglas County or Carson City, will likely be reduced by one. The statute of limitations for offering a false instrument for filing expired three years after the alleged crime, roughly a week after Ford detailed the grand jury indictment against the state electors. The other charged crime—forgery—has a four-year statute of limitations, expiring in December 2024.

Arizona

The Arizona investigation got off to a slow start. The state’s former Attorney General Mark Brnovich, a Republican who held the office through 2023, was apparently uninterested in investigating the fake electors, instead conducting a lengthy investigation into Maricopa County’s handling of the 2020 election. As a result, the state’s criminal probe appears to have kicked into motion only after Democrat Kris Mayes replaced Brnovich as the state’s chief law enforcement officer in January 2023. “We are going to investigate the fake electors,” Mayes told the Guardian in March of that year. “I can confirm that.”

The state finally unveiled charges in April 2024, over a year later. The indictment is expansive—charging a whopping 18 defendants, including all 11 of the state’s fake electors along with seven campaign aides and advisers to Trump. Some of those advisers—like John Eastman, Jenna Ellis, Rudy Giuliani, Mark Meadows, and Michael Roman—have faced charges in other states for their efforts to overturn the election. Others—Trump campaign attorneys Christina Bobb and Boris Epshteyn—are named here in criminal charges for the first time, though they’re familiar faces for those who keep close track of Trump’s retinue at Mar-a-Lago. (Bobb is currently working as the Republican National Committee’s senior counsel for “election integrity.”)

The indictment charges all 18 defendants with nine felony counts: one count of conspiracy under Arizona Revised Statutes (A.R.S.) § 13-1003; five counts of forgery under A.R.S. § 13-2002(A); and two counts of “fraudulent schemes and artifices” under A.R.S. § 13-2310(A) and one of “fraudulent schemes and practices” under A.R.S. § 13-2311. Of the latter two counts, “fraudulent schemes and artifices” criminalizes “knowingly obtain[ing] any benefit by means of false or fraudulent pretenses,” while the charge of “fraudulent schemes and practices” does not require that the defendant obtained a benefit but does criminalize “willful concealment” of a “material fact” or the use of “any false writing or document knowing such writing or document contains any false, fictitious or fraudulent statement or entry.” The charges of conspiracy and “fraudulent schemes and artifices” are felonies of the second-highest level under Arizona law, with potential sentences of between four and 12.5 years.

This structure of charges—building an indictment around forgery and fraud—is common across state-level prosecutions of fake electors. As in the Michigan, Nevada, and Georgia cases, the allegedly forged documents in question are the fake electoral certificates. The similarities continue: The Arizona indictment alleges that the conspiracy in question involved an agreement to “tamper with a public record” under A.R.S. § 13-2407(A)(3)—which recalls Michigan’s count of “uttering and publishing,” essentially charging the fake electors in that state with falsifying a public record—and “presentment of a false instrument for filing” under A.R.S. § 39-161, a charge also faced by Nevada’s fake electors under that state’s law. The Arizona conspiracy also allegedly involved a plan to alter the “vote of an elector by corrupt means or inducement,” in violation of A.R.S. § 16-1006.

But unlike these other state prosecutions, the Arizona indictment casts a wider net than most of the other prosecutions brought by state governments over the fake electors scheme. The Michigan, Nevada, and Wisconsin indictments all focused more narrowly on individuals directly involved in the machinations within each state—only the fake electors themselves in Michigan and Nevada, and only three individuals who allegedly engineered the scheme in Wisconsin. The Arizona indictment, in contrast, takes an approach more in line with the indictment brought in Georgia, broadening its scope to include figures linked to the White House and the Trump campaign—like Meadows, Giuliani, and Eastman, who allegedly coordinated the efforts to submit fake electoral certificates on a national scale.

Along those lines, there’s another key similarity between the Georgia case and the Arizona indictment: the presence of Trump himself. Trump isn’t named as a defendant, as he was in the Georgia indictment. But he is clearly identifiable throughout as “Unindicted Co-Conspirator 1.” (Four other unindicted co-conspirators appear as well, a selection of attorneys and Arizona legislators; press reports indicate that “Unindicted Co-Conspirator 4” is likely Kenneth Chesebro.)

According to an August court filing from the Arizona attorney general’s office, the grand jury expressed interest in indicting Trump as well—until prosecutors persuaded jurors not to. There’s an echo here of the Watergate grand jury, which pushed to indict Richard Nixon despite the opposition of Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski, and which ultimately settled on naming Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator.

Why did Mayes talk the grand jury out of indicting Trump? The filing is somewhat opaque, but it suggests at least two reasons.

First, the attorney general’s office may have been concerned that state charges against Trump might be duplicative of the federal charges against him over Jan. 6. (At the time the indictment was handed up, the federal case brought by Special Counsel Jack Smith was on hold as the Supreme Court weighed the question of presidential immunity.) In the same filing, prosecutors state that they provided the grand jury with a PowerPoint presentation about the Justice Department’s Petite Policy—which governs the department’s decision-making on whether to pursue a federal prosecution if law enforcement has already pursued a prior state prosecution on the same facts. The policy doesn’t apply here directly: In fact, this is arguably the reverse of the situation weighed by the Justice Department, with a state government considering charges over conduct that is already being prosecuted by the special counsel. But pointing to the policy does indicate the attorney general is concerned about pursuing a case on facts already charged by another sovereign. (Unlike some states, Arizona does not have a statutory or constitutional bar against pursuing criminal charges on a matter already prosecuted by the federal government, so Mayes had the option of pursuing charges if she desired.)

Second, it seems that the investigation may have been constrained in terms of time or resources. A selection of the grand jury transcripts included in the filing shows a representative of the attorney general’s office informing the grand jury that “our time” was “limited,” adding, “indicting somebody, even the president, is … a big deal … I don’t know if I have all the evidence to prosecute it at this moment.”

Mayes indicated at the announcement of the indictment that the investigation was ongoing. According to CNN, as of August, “prosecutors have not closed the door on potentially indicting more people, including the former president, should evidence emerge to support making that decision.” Still, any decision to bring charges against Trump would likely face serious difficulties following the Supreme Court’s decision on presidential immunity—and that’s assuming he does not secure a second term, which would require any such effort to be placed on hold. Perhaps that, too, might have informed the attorney general’s decision in requesting that the grand jury hold back from indicting the former president.

The attorney general’s office also talked the grand jurors out of indicting more than 30 other individuals, including 28 Republican members and members-elect of the Arizona state legislature. As this suggests, the jury seems to have been aggressive: According to Politico, two defendants (Bobb and Ellis) had been informed they were not targets of the investigation only days or weeks before the indictment was handed up.

In August, Mayes reached deals with two defendants, Jenna Ellis and Lorraine Pellegrino. Ellis entered into a cooperation agreement on Aug. 5, under which all charges against her were dropped. (Ellis also pleaded guilty in the Georgia case in October 2023.) Pellegrino, one of Arizona’s 11 fake electors, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of filing a false instrument and will receive three years of probation. According to the attorney general’s office, Pellegrino’s plea has been sealed, and it’s unclear whether the agreement requires her cooperation.

Mayes described her office’s agreement with Ellis as “a significant step forward for our case.” Still, if things are moving forward, they are doing so slowly. Prosecutors had asked for the trial to begin in the summer of 2025. But at a hearing on Aug. 26, Arizona Superior Court Judge Bruce Cohen set a trial date for Jan. 5, 2026—almost exactly five years after the insurrection. That date, the judge said, is a “moving target” and could be pushed back even more.

Even at this early stage, delay seems all too possible. The case is sprawling, with over a dozen defendants. And already, it’s become entangled in bizarre pretrial litigation over a recently amended Arizona anti-SLAPP law.

Anti-SLAPP laws are designed to allow defendants to speedily dismiss abusive lawsuits aimed at squelching the exercise of First Amendment rights—like the subject of unflattering reporting suing a journalist, for example. (SLAPP stands for “strategic lawsuit against public participation.”) Over half the states have some type of anti-SLAPP statute on the books. Typically, though, anti-SLAPP laws provide procedural protections against civil lawsuits. But in 2022, the Arizona legislature broke new ground by amending the state’s anti-SLAPP statute, A.R.S. § 12-751, to allow defendants to challenge criminal prosecutions as well.

Until now, that portion of the law has never been used. But many of the Arizona defendants took advantage of this change and have filed motions to dismiss the case under the statute—pitching the case headfirst into a thicket of confusion as prosecutors, defense counsel, and the judge alike struggle to make sense of an extremely puzzling law.

Eastman was first to file an anti-SLAPP motion, followed by one-time Republican Senate candidate James Lamon and Arizona State Sen. Jake Hoffman, both of whom served as fake electors. (In a twist, Hoffman himself voted for the revision to the anti-SLAPP statute in 2022.) Since then, numerous co-defendants have filed to join one or all of these motions. The arguments vary from motion to motion, but in broad strokes, the defendants generally argue that the prosecution represents an impermissible effort to “to deter, retaliate against or prevent the lawful exercise of a constitutional right” under A.R.S. § 12-751—the exercise in question being the defendants’ effort to send a slate of Trump electors to Congress in the hope of upending the electoral count, which the defendants argue was protected First Amendment activity.

During a three-day hearing in late August, Judge Cohen at times seemed visibly frustrated by the statute’s vagueness. “What was this statute designed to fix that didn’t already exist?” he asked at one point, trying to sort through how—if at all—a motion to dismiss under A.R.S. § 12-751 differs from a motion to dismiss pursuant to the Arizona Rules of Criminal Procedure. (Lamon has also filed such a motion under Rule 16.4(b) of those rules.) Should the fact that a grand jury made a probable cause determination in issuing the indictment help the state dispel accusations of bias? Given that the statute refers to the lawful exercise of a constitutional right, is it enough for the attorney general to simply argue that the defendants’ actions were unlawful—which, after all, is why they’re being prosecuted to begin with? What should he make of a puzzling amicus brief filed by the Arizona legislators who first introduced the revision to the statute, arguing that a defendant prosecuted for destruction of property after throwing a rock through a window at a protest could successfully file an anti-SLAPP motion to dismiss, if the protester could show that the “the arrest was motivated by the law enforcement agency’s political hostility to the protest”?

“I’m hard pressed to imagine that our legislature would design a statute to allow” individuals to “walk free on a criminal charge,” argued Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Klingerman at the hearing. He seemed almost as exasperated as the judge, at one point declaring, “I believe the statute is so poorly constructed that I’m not intending to concede anything on it at this point.” After the hearing, at Judge Cohen’s request, the state also filed a brief arguing that A.R.S. § 12-751 unconstitutionally conflicts with Arizona’s Rules of Criminal Procedure, infringes on executive branch discretion, and “could violate the State’s constitutional right to a jury trial in criminal cases.”

The anti-SLAPP motions have taken up the most time so far. But the docket is full of other excitement as well—such as an effort by Giuliani to obtain grand jury information in order to address his stated concern that grand jurors were biased against him, which Judge Cohen rejected as lacking “one scintilla of information” in support. Meadows, as in Georgia, also attempted to remove the case against him from state to federal court on the grounds that the conduct at issue involves his official duties as White House chief of staff. In mid-September, the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona remanded the case back to state court; Meadows has since appealed.

Wisconsin

The House Jan. 6 committee’s report and the initial federal case against Trump described the fake electors scheme in detail but left open a crucial question: Where exactly did this plan get started? Thanks to litigation in Wisconsin, the public now has an answer: the Badger State.

Wisconsin State Attorney General Josh Kaul unveiled criminal charges in June 2024 against three defendants: Kenneth Chesebro, Michael Roman (who has also been charged in Georgia), and Wisconsin attorney and Republican operative James Troupis (who, along with Chesebro, allegedly helped orchestrate the fake electors plan both in Wisconsin and nationwide). Given that it took a full three and a half years after Jan. 6 for a state to announce charges, it might seem like Wisconsin authorities have been dawdling.

By another metric, though, the attorney general’s office worked with relative speed: The first hints of a state criminal investigation first surfaced in December 2023, as reported by CNN. Just six months later, Chesebro, Roman, and Troupis faced charges. Each is charged with conspiracy to commit forgery under Wisconsin Statutes §§ 939.31 and 943.38(2)—a felony, punishable by up to six years of incarceration.

The Wisconsin prosecution followed a string of other efforts to seek accountability for the fake electors scheme outside of criminal court. Following a complaint by the nonprofit Law Forward, the Wisconsin Elections Commission twice examined whether the scheme had violated Wisconsin election law—and twice concluded it had not. (The commission had to repeat its review after controversy erupted over the fact that one of the commissioners, Robert Spindell, had himself served as a Trump elector and signed the fake electoral certificate prepared by the Trump campaign.) After the commission voted to dismiss the complaint a second time, Law Forward and Georgetown’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection (ICAP) filed a civil suit against all 10 of the Wisconsin fake electors, along with Troupis and Chesebro. The plaintiffs reached a settlement with the 10 fake electors in December 2023—under which the electors acknowledged Biden’s 2020 victory in the state and agreed not to serve as electors for Trump in the future—and, in March 2024, reached a second settlement with Troupis and Chesebro.

That settlement led to the release of an extensive collection of documents released to the public by Law Forward and ICAP, memorializing Chesebro’s and Troupis’s communications with the Trump campaign—and revealing new information about the mechanics of the effort to coordinate fake electors. The criminal charges against Chesebro, Troupis, and Roman followed just a few months later, and the charging documents cite to many of the same documents released pursuant to the settlement.

According to the criminal complaint, the nationwide fake electors strategy originated with Chesebro and Troupis in Wisconsin. In the weeks following the 2020 election, both men were “represent[ing] the Trump campaign at the time in connection with the recount in Wisconsin,” the complaint states. It was after this call, according to the attorney general, that Chesebro produced the first in the series of memos documented by both the Jan. 6 committee and the federal indictment of Trump—the Nov. 18 memo arguing for Trump electors to meet and cast their “votes” in order to preserve the campaign’s options depending on the outcome of litigation. The next week, the complaint states, Troupis passed Chesebro’s memo to “an individual affiliated with the Trump campaign.” In prosecutors’ telling, Chesebro himself was the originator of what would become the fake electors scheme, but Troupis is the missing link connecting Chesebro with the campaign itself.

As the Wisconsin complaint sets out, Chesebro would go on to produce three more memos, dated Dec. 6, Dec. 9, and Dec. 13. The latter two appear in the House Jan. 6 report; information about the Dec. 6 memo first became public when Special Counsel Jack Smith mentioned it in his indictment of Trump. In Smith’s words, the Dec. 6 memo “marked a sharp departure” from the previous memo: Instead of suggesting that the electors meet to preserve the campaign’s legal options, it shifted toward arguing that, as Smith puts it, “the alternate electors originally conceived of to preserve rights in Wisconsin instead be used in a number of states as fraudulent electors to prevent Biden from receiving the 270 electoral votes necessary to secure the presidency on January 6.”

After receiving this memo from Chesebro, according to Wisconsin prosecutors, Troupis told Chesebro that he would share it with the White House and passed both the Nov. 18 and Dec. 6 memos to “a Trump campaign consultant”—identified in the complaint only as “Individual A.” (The materials released by ICAP and Law Forward contain an email from Troupis that matches the description of this communication in the complaint and is addressed to Trump campaign adviser Boris Epshteyn.)

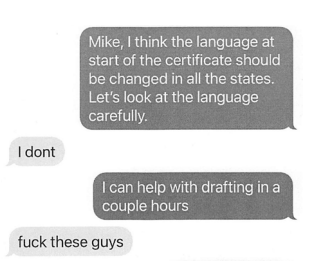

From there, it was off to the races. Troupis and Chesebro allegedly worked together to draft materials for the fake electors, coordinating with the Trump campaign through Individual A and Michael Roman. One exchange between Chesebro and Troupis—first reported on by the Detroit News in December 2023—is particularly noteworthy, concerning whether the electoral certificates should be altered to include conditional language indicating that the certificates’ use was contingent on a court’s determination that Trump had won the relevant state. The indictment includes texts from Chesebro showing that he advocated for changing the language; Roman disagreed:

(Recall that the Pennsylvania and New Mexico attorneys general indicated that the conditional wording included in those states’ fake electoral certificates played a significant part in their decision not to pursue charges against the electors. It’s possible that if Roman hadn’t rejected the conditional language, the Michigan attorney general—along with those in other swing states—would have had a harder time bringing criminal charges.)

According to the indictment, Chesebro texted Troupis on Dec. 13 that he was “working on a memo” concerning “the endgame in Congress.” On Dec. 14, the fake electors allegedly gathered to sign the certificate, with Chesebro in attendance; Chesebro texted Roman and Troupis, “WI meeting of the *real* electors is a go!!!” Two days later, Troupis, Chesebro, “and others” allegedly met with Trump at the White House. “[N]othing about our meeting with the President can be shared with anyone,” Troupis wrote Chesebro in an email afterward.

Chesebro also allegedly reviewed a document whose description matches John Eastman’s memo advocating for Pence to upend the electoral count, responding over email, “Really awesome.” In the days leading up to Jan. 6, the complaint states, the three defendants worked to coordinate the delivery of the fake electoral certificates to Congress.

The Wisconsin case has been quiet since the release of the criminal complaint in June. The defendants were initially scheduled to appear in court this September, but their appearance has been delayed until Dec. 12. No other information is available on the public docket.

What Next?

These prosecutions are not a panacea—especially given the bumps they’ve faced along the way. According to CNN, many of the individuals who served as fake electors the last time around are signed up as Trump electors once again. Two of the current Republican electors in Nevada, and six in Michigan, are among those who have faced criminal charges for their role in 2020.

Still, though, the state cases are an important part of a larger effort to respond to Jan. 6. Any repeat of the fake electors scheme in 2024 would face significantly more difficulty this time around, thanks to legal changes passed by Congress in the Electoral Count Reform Act. New legal barriers arose from other sources as well, like the Wisconsin civil settlement that barred the defendants from serving as electors again. And it seems that at least one former fake elector facing charges has been chastened by the experience: Georgia State Sen. Shawn Still, whose criminal case remains pending in that state, vowed to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in October that he would never again serve as an elector “knowing what I’ve been through.” Whichever candidate wins Georgia, he told the paper, “I’m going to follow our governor and secretary of state and support their certification of the vote.”

In the event of a victory for Vice President Kamala Harris, these prosecutions might serve as a deterrent to a Trump campaign strategizing creatively to overturn the lawful results of the election. In the event of a victory for Trump, they will take on a different significance. With the instigator himself shielded from prosecution, these state cases will represent a remaining viable path forward for seeking criminal accountability for Jan. 6. And while Trump has promised to pardon the Jan. 6 rioters who faced federal prosecution, state charges—if they hold up in court—are not the president’s to wipe away.