A Whistleblower Incentive Program to Enforce U.S. Export Controls

In the years after the 2008 financial crisis, Bank of America’s Merrill Lynch brokerage unit began using accounting tricks to withdraw billions of dollars of customer funds for use in its own trading operations. This was illegal: Had Merill Lynch failed during this time, its customers would not have had enough cash in the reserve account to cover their claims.

This scheme was brought to light by insider whistleblowers, resulting in a 2016 Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) action in which Merrill admitted wrongdoing and paid a $415 million settlement—one of the largest ever against a Wall Street bank. Two years later, the SEC awarded the three anonymous whistleblowers a combined $83 million for reporting the misconduct.

The reward was paid out as part of the SEC’s whistleblower program, created as part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. This highly successful program has become an integral part of the SEC’s efforts to surface information of wrongdoing, awarding more than $2.2 billion to whistleblowers since its inception and therefore (because whistleblowers are awarded between 10 and 30 percent of the penalty) aiding between $7 billion and $22 billion in penalties during that time. Its effect on law violations is understudied, but existing research suggests it has reduced financial reporting fraud, deterred insider trading, and caused companies to strengthen their compliance programs.

In April, Sens. Mike Rounds (R-S.D.) and Mark Warner (D-Va.) introduced legislation to establish a Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) whistleblower incentive program modeled on the SEC program. The BIS is the agency responsible for administering and enforcing U.S. export controls. It is currently struggling to meet its growing responsibilities: managing the wide-ranging export controls on artificial intelligence (AI) chips and chip-making tools as well as preventing technology diversion to Russia following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Two important reasons for these difficulties are the BIS’s reliance on outdated technology and its staffing shortage. For example, at the time of this writing, a single export control officer is responsible for investigating violations and conducting inspections across all of Southeast Asia and Australasia.

A whistleblower incentive program could strengthen the BIS’s enforcement ability by offering substantial financial rewards and protections to insiders who report export law violations, while potentially paying for itself. Potential whistleblowers could include employees of U.S. exporters, server manufacturers, and distributors, as well as of resellers and data center operators on the ground in common re-export locations—many of whom are well-positioned to identify and report on violations. Such a program would avoid needing an increase in the BIS’s budget by funding it entirely by monetary penalties collected from violators and would likely even pay for itself by generating additional penalties for violations that otherwise would have gone undetected.

Export Enforcement Failures

Export enforcement has been notably ineffective in AI chip export controls against China and other countries of concern since they were introduced in 2022. Advanced AI chips are the foundational hardware required to train and run sophisticated AI models, making their availability a critical bottleneck for any nation’s AI capabilities.

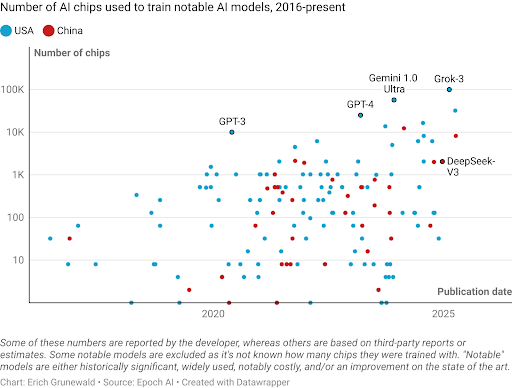

As shown in Figure 1, frontier AI models are now built using tens or even hundreds of thousands of advanced AI chips, each costing tens of thousands of dollars. For example, xAI’s Grok 3 model was trained on the Colossus cluster in Memphis, which at the time contained 100,000 NVIDIA H100 chips worth around $2.5 billion. Because these chips are so valuable and in such high demand, there are strong incentives for bad actors to smuggle them into China and other countries where their export is prohibited.

Figure 1. AI models are trained with increasing quantities of AI chips.

Although the AI chip controls have had a real impact on China’s AI industry—as leaders from companies such as DeepSeek, Tencent, and Alibaba have acknowledged—persistent enforcement failures have made these export controls significantly less effective than they could be. For example, smugglers have funneled substantial quantities of advanced AI chips into China. A Chinese start-up founder estimated in 2024 that there were more than 100,000 NVIDIA H100s in China—the sum of which is the size of some of the world’s largest supercomputers. (The H100 has never been legally available in China.) Three reported cases alone in 2024—substantiated by interviews with smugglers, procurement records, and warehouse visits—amounted to nearly 10,000 NVIDIA H100s collectively (worth approximately $230 million) being moved to China, and there is almost certainly a large number of unrecorded cases. In February, Singaporean authorities arrested three individuals suspected of diverting AI servers worth $390 million to China. Russia has also benefited from these illicit networks, with one reported case involving servers worth approximately $300 million (containing nearly 9,000 H100s) diverted to Russia through an Indian pharmaceutical company.

Export violations have also helped China develop domestic alternatives to American AI chips. Most notably, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) reportedly manufactured enough chip dies for Huawei to produce more than 1 million Ascend 910C accelerators. The Ascend 910C is China’s most powerful AI chip, approximately four years behind NVIDIA’s technology. According to Reuters, TSMC could face a penalty of more than $1 billion for this violation.

Export controls on AI chips are difficult to enforce mainly because neither the BIS nor exporting companies have full visibility into these chips’ final destinations or ultimate owners. That is partly because exporters are subject to criminal penalties only if they willfully commit a violation of the rules, and the BIS is reportedly reluctant to impose civil penalties without evidence that a company had positive “knowledge” of a violation. This lack of transparency is a general challenge in export enforcement. For example, the TSMC violation was uncovered only after the independent research firm TechInsights discovered that a Huawei Ascend chip appeared to have been manufactured at TSMC. After being notified by TechInsights, TSMC reported the violation to U.S. authorities, but by then millions of chips had already been shipped to China.

The Proposed Whistleblower Incentive Program

The whistleblower program proposed in the bipartisan Rounds-Warner bill—aptly named the Stop Stealing Our Chips Act—would incentivize people with knowledge of violations to come forward by providing whistleblowers with 10 to 30 percent of any resulting penalty and offering confidentiality and protections against retaliation. (Unlike qui tam laws where individuals sue violators directly, this program follows the SEC model where whistleblowers report to the government agency, which then investigates and collects penalties.) These are powerful incentives. As mentioned, several reported instances of AI chip smuggling from 2024 alone involved shipments worth more than $100 million each. Since the BIS can administer civil penalties up to twice the value of the transaction, a whistleblower could have been rewarded tens of millions for reporting on them. If an insider had reported the TSMC violation to the BIS, they could have been rewarded more than $150 million under such a program, even if only half the chips had been manufactured at that point.

In addition to offering high monetary awards and robust protections, a successful whistleblower program must rapidly review and take action on whistleblower reports. Long turnaround times have reduced the effectiveness of other whistleblower programs. An insider will most likely not risk their career and more to report a violation if it will take a decade of grinding uncertainty to receive a reward.

To ensure whistleblower reports are reviewed and acted on promptly, the BIS would need to hire additional staff and establish effective procedures for reviewing and investigating these reports. It would also need to invest in educating businesses and individuals about the program and doing any necessary record-keeping and reporting. But the BIS is infamously strapped for cash—its $191 million budget is approximately the cost of two F-35 Lightning II fighters per year. So how would it pay for these activities?

The Rounds-Warner bill addresses this problem by establishing an “Export Compliance Accountability Fund” financed by monetary penalties paid by export law violators. This fund has a direct precedent in the SEC’s Investor Protection Fund. In addition to paying awards to whistleblowers, the fund would be used to support those other activities needed to run the program. As a result, the BIS would not need additional appropriations to set up and run the program. If the program results in penalties that wouldn’t have been levied otherwise, which seems likely, it could even reduce the federal deficit by generating additional income for the government.

Potential Drawbacks

A few additional concerns arise for any program that offers strong whistleblower incentives and is funded purely through penalties.

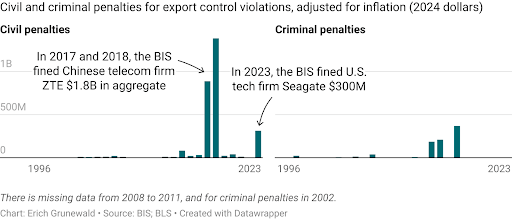

First, there is a bootstrapping problem: Can the program ever get off the ground if it relies on incentives to generate penalties, while simultaneously needing those penalties to establish the very program that creates the incentives? The answer is likely yes. As shown in Figure 2, the BIS is already generating significant penalties every year, without any substantial whistleblower incentives. Since 1996, the median annual penalty including both criminal and civil cases has been $13 million adjusted for inflation. In addition, a few years have seen penalties worth hundreds of million imposed on violators. This existing revenue should be enough for the program to establish itself and grow quickly over one or two years.

Figure 2. In a typical year, the BIS levies over $13 million in penalties, but some years have seen penalties well over $100 million.

Second, large whistleblower rewards could encourage people to deliberately stage wrongdoing to claim the reward money. But such schemes rarely make financial sense. If someone stages a violation and reports it, the violator must pay the full penalty (say $10 million), while the whistleblower only receives a fraction of that amount (between $1 million and $3 million). In other words, the conspirators would lose money overall. A whistleblower could profit only by causing someone else—for example, their employer—to break export rules, and then reporting the violation to collect a reward while the other party foots the bill for the penalty. But this type of scheme is extremely unlikely—there do not appear to be any known examples of it happening for other successful whistleblower programs. Even if someone were to try this strategy, such attempts would simply help the BIS identify weaknesses in companies’ compliance processes.

Third, a whistleblower program could affect companies’ ability to operate abroad by unintentionally encouraging employees to make false or exaggerated reports to the BIS, or to withhold information from the company in favor of reporting it directly to the BIS. Employees could be tempted to do this by the prospect of large financial rewards, even if they are extremely unlikely to actually collect any reward. Partly due to these concerns, whistleblower programs have included safeguards against abuse. For example, the SEC program requires whistleblowers to swear under oath that their information is truthful, and it bans those who file frivolous reports from making further reports. It also promotes internal reporting by rewarding whistleblowers who first raise concerns within their organizations and allowing whistleblowers to receive compensation even if their company self-reports to the SEC following an internal complaint. And, of course, these programs always review reports before taking action based on them—as would the BIS program proposed in the Rounds-Warner bill.

The fourth concern is the most notable and difficult to predict. Many export law violations today happen abroad and involve companies without any U.S. presence. For example, AI chip smuggling seems to frequently involve small resellers in places such as Singapore or Malaysia. This limits the BIS’s ability to act on whistleblower reports in two ways. First, it is more difficult to levy penalties on companies that lack a U.S. presence, as doing so may necessitate a diplomatic process with the foreign government. Because they depend on the cooperation of foreign governments that may not share the BIS’s priorities, and because they require more coordination between different parties, such processes are slower and less effective than enforcement against U.S. companies. Second, these smaller companies may be unable to pay penalties appropriate for large-scale diversions.

If the BIS cannot effectively penalize violators, potential whistleblowers would have little incentive to report suspicious activities, since they are unlikely to receive rewards. But despite these challenges, a BIS whistleblower program could still be highly impactful. Many of the companies involved are large and do have a significant U.S. presence. For example, a report by short-seller Hindenburg Research documents multiple compliance failures by AI server builder Supermicro alleging that it has supplied millions of dollars of products to a distributor in Russia through a California entity, despite sanctions. Supermicro is headquartered in California. Even foreign companies often have substantial stakes in the U.S., whether through assets, business relationships, or involvement in the U.S. financial system. TSMC, which likely violated U.S. export law by manufacturing chips for Huawei, falls into this category. And as mentioned, the BIS’s track record of penalizing domestic and foreign companies for export violations shows that there are many export law violations that can be penalized.

An SEC-style whistleblower program is not the only way to incentivize individuals to report violations. Another option would be to authorize qui tam lawsuits against those who violate export law, allowing individuals to sue a violator and collect a portion of the resulting penalty. This approach would be modeled on the False Claims Act of 1863, designed to uncover fraud against the government. In 2022, approximately 90 percent of the $2.2 billion recovered under the False Claims Act came through qui tam cases. (There is some legal uncertainty around qui tam suits. Although they have been practiced since the 19th century, a judge from the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida ruled them unconstitutional in 2024. The decision is currently being appealed, and the U.S. government has urged the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals to overturn it. However, if the ruling stands, a qui tam authorization for the BIS would be more difficult.) This authority could even exist alongside a whistleblower incentive program.

***

There is no perfect solution to export control enforcement. Controls on AI chips will never be watertight, but by limiting the overall computing power available to China’s AI industry—whether for military or other purposes—they help maintain America’s technological leadership. A thoughtfully designed whistleblower incentive program would help deter potential violators and catch violations, while generating additional revenue for the federal government.