An Israeli Gap in Drone Defenses

I am not fit to comment on politics, motivation, or larger intelligence failures in the Gaza Strip, but one piece of video released, purportedly showing a Hamas attack on an active Israeli Merkava 4 tank, if true, shows a woeful preparedness gap in the Israeli military that may also affect the U.S. military.

Hamas should not have been able to launch this particular drone attack. Why?

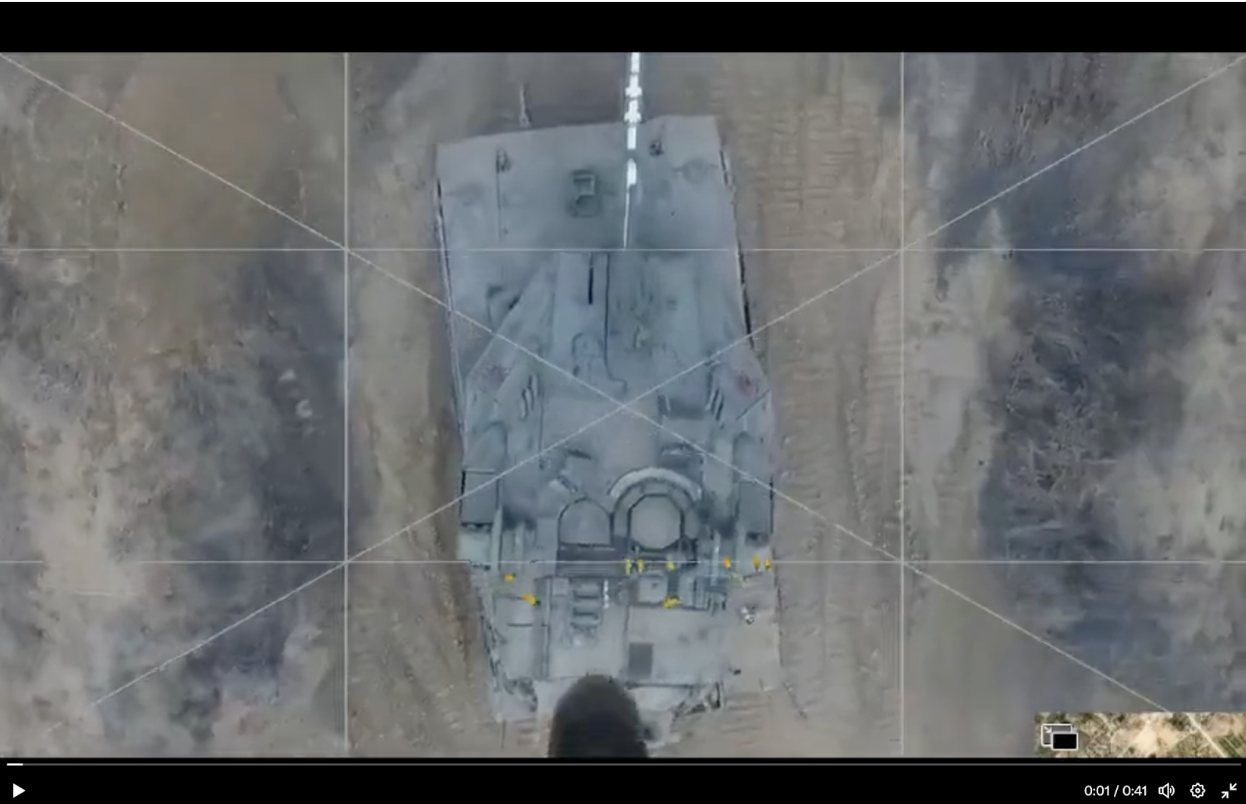

This footage seems like so much of the previous small drone footage we have seen over the past half decade: A hovering drone looks down over a target at an altitude of roughly 30 meters (100 feet) in the air, releases a munition, and then the target blows up. The drone then shows the aftermath of the attack, with the tank in this case suffering damage and components left burning as the drone flies away. Multiple reports have now used this video, although Hamas’s web site is currently down and I don’t have access to their Telegram channels so I can’t validate it personally.

The disturbing part of the video is that it happened at all and suggests multiple failures in preparedness. The footage itself, captured from the operator’s screen, shows that this drone was almost certainly a common DJI model (based on portions of the user interface seen throughout the video), although I cannot identify the particular model (Editor's note: DJI has not responded to a request for comment, and we will update this piece if and when it does.)

Typical DJIs that may be used for this purpose (and were seen being used this way in Ukraine) would be from the Mavic line of “prosumer” drones. The Mavic drones are relatively small, weighing just under a kilogram and with a theoretical 40 minutes of flight time and a 15-kilometer remote range. They are also not that expensive, with a Mavic 3 Pro costing just $2,200. Of course, adding a payload reduces the flight time but a 250-gram payload, roughly the weight of a grenade, can be added without significantly harming performance. A payload release can easily be added or even just purchased from Amazon.

At first glance, the video seems legitimate, as it doesn’t include the “this is a video game” features of faked videos where things don’t move quite right. Likewise, this video includes artifacts that are common to how digital transmissions respond to noise, glitches which the standard video games like “Arma 3” (a popular source for generating faked videos) do not include in the videos.

To begin with, an out-of-the-box DJI has enforced geofencing, due to software in the drone that prohibits its functioning in geographic areas specified by the local government and reported to DJI. Did the Israeli government not ask DJI to enforce a no-fly zone in the Gaza Strip and surrounding area? If they didn’t, why didn’t they? Did the Israeli government ask and DJI refused? Or was the DJI “jailbroken” to remove the restrictions?

All three cases have substantial policy implications. The first suggests malpractice by the Israeli government. The second implies near criminal behavior on the part of DJI. And the third is a reminder that such software restrictions can be bypassed by a determined owner and are best thought of as keeping honest pilots honest, not a security measure against malicious drones. DJI responded to my request for comment that they did not receive requests from any parties to enforce no-fly-zones in this conflict area. In addition they strongly denounce the use of their products in any combat operations. This suggests that it is the first scenario: Israel had never reached out to DJI prior to the attacks to enforce a No Fly zone in Gaza, although it does not preclude the attacker still jailbreaking the drone to bypass other restrictions.

A DJI drone is also easy to detect. Although DJI itself sells a $10,000 drone detection system, any similar system should pick up an active DJI, thanks to several features that contribute to easy detection: DJI drones are highly ubiquitous, with well-known broadcasting behavior in the unlicensed (2.4 and 5.7 GHz) bands. That is even before considering that, unless jailbroken, a DJI drone literally broadcasts its exact location and the operator’s location once a second on the unlicensed bands to anyone in the area listening in with a COTS software-defined radio!

Finally, although the next generation of military-specific offensive drones will resist jamming (a jamming system broadcasts just enough radio interference to render the control link inoperable, effectively just outshouting the legitimate transmitters), these civilian drones are trivial to jam.

Any modern military-centric drone detection system should be able to block a DJI drone’s ability to receive instructions without a metaphorical sweat using such jamming. Which says either the Israeli military never purchased such anti-drone systems, did not deploy anti-drone systems around Gaza, or did not turn on these systems, or the products they bought were snake-oil systems, incapable of dealing with the easiest possible threat.

ISIS first started using armed DJI drones over 5 years ago, initially with great success until the U.S. military deployed jammers for both U.S. and Iraqi forces. This is a threat that militaries have known how to handle and counter for a few years now, and if any piece of equipment should have self-contained countermeasures against such a foreseeable attack, it should be a main battle tank.

That one of the most advanced and well-equipped militaries in the world should fall victim to such an easily countered attack is disturbing. U.S. military planners should ask themselves: “Could this happen to us?”