The Situation: I Never Signed Up for This Kind of Targeted Killing

And it’s a profoundly dangerous power for any president to have

The Situation on Wednesday basked ever so briefly in good news from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on the Alien Enemies Act.

Today, let’s talk “boat boom.”

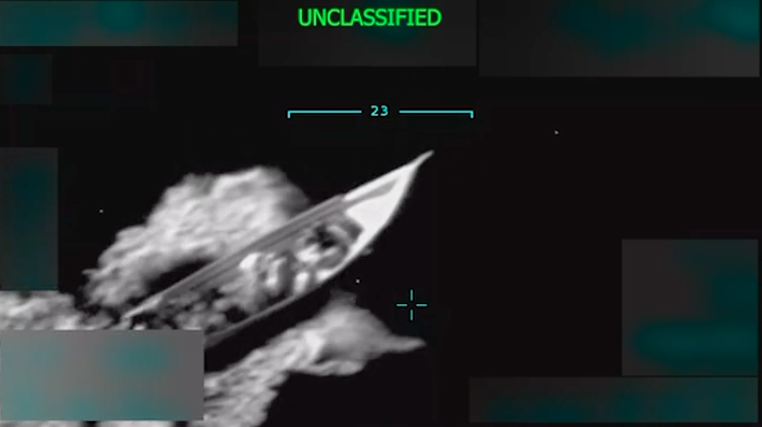

For those who want a careful legal analysis of the strike U.S. forces conducted in the Caribbean Sea on a boat allegedly carrying Tren de Aragua members—and drugs—toward the United States, my colleague Scott R. Anderson has you covered. His detailed article goes through the various legal questions raised by the strike in some detail: Is there domestic legal authority? Does it violate the international law of armed conflict? Does it violate U.S. criminal law? I also discussed these questions with Anderson and with Rebecca Ingber of the Cardozo School of Law on Thursday on Lawfare Live:

Here, however, I want to approach the matter from a less technically legal, more impressionistic perspective, because I actually think all of this attention to the details of the law—which is what we do at Lawfare and for which I am in no sense apologizing—may obscure the magnitude of what the administration did this week.

Because as the Gen-Zers might put it on Instagram or TikTok, “OMG, guys! The U.S. military just unalived 11 civilians on a boat! On purpose!”

Now I want to stress that I am emphatically not an opponent of targeted strikes against enemy individuals or small groups.

In Lawfare’s more formative years, I was one of the most vocal public supporters of the drone strike that killed Anwar Al-Aulaqi. Indeed, over the many years that the drone strike program of the Bush and Obama administrations roiled public debate, I was a vociferous defender of the program, which I believe to this day made a critical contribution in dismantling of al-Qaeda’s terrorist capacity in several key locations around the world.

I do not in any sense recant that support for the drone program and for targeted killing of enemy military leadership more generally. What’s more, I consider my enthusiasm for the responsible deployment of drones for lethal purposes to have been largely vindicated by their robust use in a more defensive and conventionally military context by Ukrainian forces over the past few years.

So it is not as an opponent of the use of drones or targeted killings, but as a defender, that I say that this strike should not merely never have taken place. It should have been unthinkable.

Let us flag the key differences between this strike and the ones conducted by prior administrations.

The first and most important difference is that those past strikes targeted people genuinely believed to be operational figures in terrorist groups who were at least plausibly covered by a congressional authorization to use military force (AUMF), which was worded broadly to cover a broad range of worldwide operations. Yes, there were sometimes civilian casualties. And yes, there were mistakes.

But in no prior strike of which I am aware has the United States government targeted with lethal force people known to be civilians unconnected to any group against which Congress has authorized force in a context it has always regarded as the province of the criminal law. If you can think of a case, please let me know. I cannot.

What’s more, in no previous strike of which I am aware has the government taken the position, in the absence of an act of Congress, that groups are targetable with lethal force merely because of some combination of the fact that they are designated foreign terrorist organizations and because the president has determined that “we have now reached a critical point where we must meet [the] threat to our citizens and our most vital national interests” from their various activities “with United States military force in self-defense.” The administration’s statement of its legal authority to conduct this strike deliberately obscures what its actual basis is, but it seems to be some combination of the fact that other countries aren’t doing enough about the cartels, the cartels are now designated foreign terrorists, and the president is fed up.

Members of Tren de Aragua seem like a nasty lot. But if the president can with a wave of his hand make them legitimate military targets, why can’t he do the same thing with, say, Nigerian phone scammers or Chinese manufacturers of drug precursor chemicals?

Indeed, the government here barely even pretends that the action was taken in self-defense—even as that term has been expansively understood in prior executive branch legal argumentation. Sure, the president’s 48-hour war powers report, quoted above, invokes the phrase. But none of the usual preconditions for a claim of self-defense are present here. The government does not claim that the boat was on its way to attack the United States or conduct military operations against it or that it was part of a broader pattern of activity leading to that outcome. Rather, the alleged drug trafficking is the supposed military action. While the government claims that Tren de Aragua has engaged in terrorism, it doesn’t claim that this boat was on its way to do so or that attacking it helped in any way to make such action less likely.

This brings me to another important difference between this strike and the ones I have supported: the presence of alternatives. When you’re dealing with terrorist operatives halfway around the world in areas where you don’t have troops on the ground, the alternative to an airstrike can be a very dangerous ground operation. And sometimes, there is no realistic alternative. When you’re dealing with one small boat heading to one’s own territory in international waters and the United States Coast Guard is available, there are plenty of options short of blowing up that boat—options that involve lesser uses of force. One can force such a boat to turn around, deny it entry to U.S. waters, interdict it and seize its cargo, arrest and prosecute or deport its crew. There is no good reason to blow it up as a matter of first resort. Unless you’re bloodthirsty, that is, or you want to send a message. Neither is a legitimate reason.

Indeed, as Secretary of State Marco Rubio made clear, the United States could have interdicted the boat and chose not to: “Instead of interdicting it, on the president’s orders, we blew it up. And it’ll happen again. Maybe it’s happening right now,” Rubio said, according to CNN.

In other words, the United States targeted with lethal force people it believed to be civilian drug traffickers and acknowledged that it could have stopped them. This would be illegal for cops. And it should be unthinkable for the military too. When I supported drone strikes against terrorist leaders actively plotting attacks against the United States overseas, I never signed up for such a notion. Frankly, the action seems far closer to simple murder than it does to the drone strikes program of the past.

Finally—and call me old-fashioned for still believing this—but carrying contraband is just not the same thing, morally or legally, as attacking a country militarily. Yes, drugs kill a lot of people. Yes, the cartels are a scourge. And yes, they engage in violent, sometimes even terroristic, acts of various sorts. I’m all for going after the cartels, and I’m not even opposed—sometimes, and under the right conditions—to the use of lethal force to do it. When, for example, violence is underway, I have no problem with cops using violence to stop it—and when violence or death is imminent, it is legitimate to prevent it with the use of lethal force too.

But the circumstances under which the administration is now allowing lethal force against mobsters and gang members and cartels engaged in drug trafficking and associated violence are emphatically not the same as the circumstances in which we permit lethal force against belligerents conducting military attacks on the United States.

And at least until Congress tells me otherwise by authorizing the use of military force against Tren de Aragua and the other gangs, I’m going to draw a pretty bright line on this point: Cartel and gang members are not combatants in an armed conflict against the United States. And unless they are engaged in an ongoing or imminent military attack against the United States, it simply isn’t self-defense to attack them with lethal force either.

I am aware that lawyers for the administration will argue that the second point is more complicated than I am allowing here—that the executive branch has long claimed a space for U.S. military actions under domestic law in the absence of congressional authorization and in circumstances beyond strict self-defense.

But I’m sorry. This boat isn’t Libya. And this boat isn’t Serbia. This is a small craft allegedly carrying drugs and allegedly piloted by criminals not remotely connected to an armed conflict in which the United States or any ally is involved. If the president can blow it up using his war powers, I fail to see why he can’t also deploy the military domestically to use lethal force against supposed Tren de Aragua facilities or groupings that might be engaged in activity he might think warrants similar American “self-defense.”

There has to be a limit to the president’s power to use military force instead of law enforcement authorities. That line had been defined imperfectly but relatively stably, for the past more-than-two decades by a combination of the 2001 AUMF broadly interpreted and a robust but not infinite notion of self-defense. The attack in the Caribbean explodes this line in a fashion we will be reckoning with for years to come.

If, that is, we bother reckoning with it at all. The president is betting that nobody will bother.

I very much pray he’s wrong, even as I fear he may be right.

The Situation continues tomorrow.