Did the President’s Strike on Tren de Aragua Violate the Law?

By applying the tools of war to civilians, the Trump administration is entering unprecedented—and deeply problematic—legal territory.

Editor’s note: Listen to a live discussion from Sept. 4 on the legality of the Venezuelan “boat strike” with Scott R. Anderson, Rebecca Ingber, and Benjamin Wittes here.

(Following publication, the Trump administration's 48-hour War Powers report to Congress entered the public domain. It confirms that the Trump administration is relying on the president’s Article II constitutional authority as the domestic legal basis for its actions, and maintains that it was acting pursuant to the United States’s inherent right of self-defense as a matter of international law.)

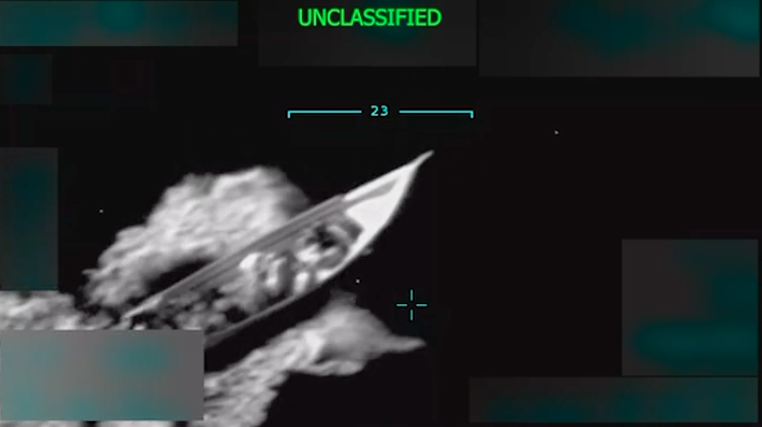

At an unrelated Oval Office event on Tuesday, Sept. 2, President Donald Trump casually mentioned to reporters that the United States had “literally shot out a boat, a drug carrying boat” just minutes earlier. Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed the president’s account shortly thereafter, tweeting that “the U.S. military [had] conducted a lethal strike in the southern Carribean [sic] against a drug vessel which had departed from Venezuela and was being operated by a designated narco-terrorist organization.” A few hours later, Trump himself shared a more detailed account of the strike—including a video—on his social media platform Truth Social, stating:

Earlier this morning, on my Orders, U.S. Military Forces conducted a kinetic strike against positively identified Tren de Aragua Narcoterrorists in the SOUTHCOM area of responsibility. TDA is a designated Foreign Terrorist Organization, operating under the control of Nicolas Maduro, responsible for mass murder, drug trafficking, sex trafficking, and acts of violence and terror across the United States and Western Hemisphere. The strike occurred while the terrorists were at sea in International waters transporting illegal narcotics, heading to the United States. The strike resulted in 11 terrorists killed in action. No U.S. Forces were harmed in this strike. Please let this serve as notice to anybody even thinking about bringing drugs into the United States of America. BEWARE! Thank you for your attention to this matter!!!!!!!!!!!

As of publication, the Trump administration has not provided an official account of the legal basis for its actions. Nor is it clear whether it has provided Congress with a report providing such an account, as it is statutorily required to do within 48 hours of U.S. armed forces being “introduced … into hostilities.” But various officials have hinted at the administration’s likely rationale. The deputy press secretary at the White House has stated that the strike was “conducted against the operations of a designated terrorist organization and was taken in defense of vital U.S. national interests and in the collective self-defense of other nations who have long suffered due to the narcotics trafficking and violent cartel activities of such organizations.” Rubio, for his part, indicated separately, “[I]nstead of interdicting [the boat], on the president’s orders, we blew it up — and it’ll happen again …. The president has a right to eliminate immediate threats to the United States.”

In many ways, the Trump administration’s actions aren’t a complete surprise. Figures in Trump’s circles have discussed the possibility of using military force against drug traffickers for some time, to the point that Republicans introduced draft legislation authorizing such action in the last Congress. (Notably, legal scholars Ashley Deeks and Matthew Waxman examined the legal basis for such military operations at the time for Lawfare, and much of their analysis applies to the present situation.) A few weeks before the strike, the New York Times reported that Trump had authorized the military to take action against “certain Latin American drug cartels that his administration has deemed terrorist organizations,” up to and including lethal force. And more recently, the U.S. military had positioned substantial naval assets in the southern Caribbean, leading some analysts to conclude military action of some sort was likely forthcoming. Moreover, in the post-9/11 era, U.S. strikes on purported terrorist groups have become a familiar occurrence.

Such appearances, however, risk obscuring the novelty of what the Trump administration has done. By targeting narcotics traffickers with lethal force—even when interdiction, by Rubio’s account, was an available option—the Trump administration has taken the tools of warfare and applied them to a group that the United States has historically sought to protect from such targeting: civilians, even when engaged in harmful and criminal behavior. Doing so raises substantial questions of domestic and international law. They, in turn, raise even more questions about the president’s constitutional authority to undertake such actions in the first place.

What Is the Legal Basis for the Strike?

As a matter of U.S. domestic law, military action directed by the president must be either authorized by Congress through statute or pursuant to the president’s inherent authority under Article II of the Constitution.

There is no colorable statutory authority for military action against Tren de Aragua and other similarly situated groups. Occasional suggestions in the press that the Trump administration’s description of Tren de Aragua as a terrorist organization is meant to invoke the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) are almost certainly mistaken: That authorization extends only to the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks and select associates, and no one—not even in the Trump administration—has accused Tren de Aragua of being that. Nor does the oft-cited fact that the Trump administration has designated Tren de Aragua as both a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) and a specially designated global terrorist (SDGT) make any difference. The statutes, executive orders, and regulations underlying these two terrorist designation regimes authorize economic sanctions and select other measures, but say nothing about the use of military force. FTO or SDGT designation may make a difference in how certain internal executive branch policies relating to the use of force apply to such groups. But it has no bearing on the broader question of the president’s legal authority to order the use of military force against them in the first place.

Instead, the Trump administration’s scattered statements suggest that it is almost certainly relying on President Trump’s Article II constitutional authority. The executive branch has long maintained that Article II gives the president broad inherent constitutional authority to use military force without congressional authorization. Such views have proved controversial among legal scholars and have never been fully vindicated in the federal courts. But most judges have been reluctant to put limits on the executive branch’s actions absent clear statutory restrictions by Congress, which—with the limited (and somewhat flawed) exception of the 1973 War Powers Resolution—have not been forthcoming. As a result, the executive branch’s broad views of presidential authority remain the operational ones for purposes of informing U.S. military actions.

Past presidents have sometimes framed the president’s inherent constitutional authority to use military force as essentially plenary. But most recent administrations—including the first Trump administration—have instead argued that, “at least insofar as Congress has not specifically restricted it,” this authority extends to situations where the president can reasonably determine that the anticipated military actions will (a) “serve sufficiently important national interests” and (b) be of a “nature, scope, and duration” that does not rise to the level of “a war requiring prior specific congressional approval under the Declaration of War Clause”—a threshold the executive branch equates with “prolonged and substantial military engagements[.]” Congress has in turn set certain limits on this authority through the aforementioned War Powers Resolution, most notably by requiring the president to “terminate” any military operation that lacks congressional authorization after 60 to 90 days absent certain extenuating circumstances. While some past presidents have argued that this restriction is unconstitutional, recent ones have rarely contested it. That said, the executive branch has occasionally suggested—including during the first Trump administration—that neither the Declare War Clause nor statutory limitations apply in certain circumstances where the president is acting in national self-defense, as he has some exclusive constitutional authority to do so.

On first impression, the recent strike on Tren de Aragua seems to fit comfortably within this framework. The “national interests” prong of the above two-part test is not particularly constraining. Past presidents have justified far more substantial military action on such flexible national interests as promoting regional stability in areas far further afield than the Caribbean, which the United States has long identified as an area of special concern to its national interests. A similar logic could readily apply to narcotics trafficking given its well-documented impact on the United States and broader Western Hemisphere. And it seems unlikely that Tren de Aragua (or even Venezuela) will be able and willing to mount a military response whose “nature, scope, and duration” rise to the level of a “war for constitutional purposes” so as to implicate possible Declare War Clause limitations. If this most recent strike proves to be the beginning of a longer campaign, then it may eventually raise questions about the War Powers Resolution’s 60- to 90-day cutoff. But that deadline remains a ways off, and, in any event, the executive branch has long employed legal interpretations that limit this requirement’s application to campaigns involving intermittent military operations, none of which have been the subject of meaningful pushback by Congress or the federal courts. In short, on their face, the Trump administration’s actions appear consistent with the permissive standards applied by the executive branch when it comes to the use of force.

Yet this analysis elides a key fact that distinguishes the Trump administration’s recent strike from the actions of its predecessors: Here, for the first time in recent memory, the United States has directly targeted individuals who are traditionally understood to be civilians. This isn’t one of the variables in the test put forward by the executive branch. But it’s still a distinction with potential legal significance.

Of course, the Trump administration would almost certainly contest this characterization. As Trump has made clear in recent proclamations, his administration views Tren de Aragua as a terrorist group “undertaking hostile actions” toward and “conducting irregular warfare” against the United States through unlawful immigration, narcotics trafficking, and criminal violence. In their view, this most likely makes the 11 individuals killed on the targeted ship—all of whom it claims to have “positively identified” as members of Tren de Aragua—permissible targets, in the same way that other terrorist groups hostile to the United States may be (and frequently have been) targeted using the president’s Article II authority.

The problem for the Trump administration is that this account is hard to square with how the United States has traditionally approached such military operations in the past, particularly in relation to the international law of armed conflict. And as discussed further below, this tension could in turn have ramifications for both U.S. criminal law and the president’s constitutional authority to undertake such actions in the first place.

Did the Strike Violate International Law?

The Trump administration’s attack on the Tren de Aragua ship potentially implicates (at least) three areas of international law: jus ad bellum, which addresses the lawfulness of resorting to war; jus in bello, which addresses the lawfulness of the conduct of war; and international human rights law. And it raises serious questions under all three.

Jus ad Bellum

At least since the adoption of the UN Charter in 1945, international law has generally prohibited the use of force between states except where authorized by the UN Security Council. As the U.S. strike took place in international waters against a ship that does not appear to have been flagged to a particular country, it is not clear that the United States used force in this case directly against another state. But as it claims to have killed Venezuelan nationals—and the United States has elsewhere suggested that targeting the nationals of a state can constitute an armed attack—the Trump administration’s actions nonetheless implicate this restriction on the use of force, as its own statements appear to acknowledge.

Article 51 of the UN Charter, however, makes clear that this restriction does not “impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs” or, as most authorities interpret it, is imminent. This means a state can still use military force in individual self-defense in response to an imminent or actual armed attack, or in collective self-defense of another state if that state requests its assistance in exercising its own right to self-defense. In this case, the Trump administration has suggested that it is acting pursuant to both, on its own behalf and on behalf of other states similarly affected by trafficking in narcotics and illegal immigration. But as it is unclear whether any other state has actually made a request, individual self-defense appears to be the administration’s primary international legal justification.

Most of the international community sets a high bar for when an armed attack has occurred or is imminent. The International Court of Justice has held that uses of force must entail substantial “scale and effects” to constitute an armed attack, at a level above “mere frontier incident[s]” and other minor violent exchanges. But the United States has long dissented from this view. Instead, it has posited that any illegal use of force can trigger the right to self-defense, and that imminence hangs on a variety of factors ranging from the severity of the anticipated attack to patterns of activity by the expected attacker. Yet it has also maintained that certain coercive actions, like the imposition of economic sanctions, cannot constitute an armed attack. The main distinction that the executive branch has articulated—specifically in the cyber context—is whether the actions result in “direct physical injury and property damage … like that which would be considered a use of force if produced by kinetic weapons.” Regardless, the two main purportedly hostile acts that the Trump administration attributes to Tren de Aragua—narcotics trafficking and facilitating unlawful immigration—seem unlikely to qualify as an armed attack under either standard. (Deeks and Waxman reach the same conclusion in their analysis.)

Actual acts of violence that Tren de Aragua is alleged to have undertaken—such as murder and assault in support of its criminal activities—against the United States or U.S. nationals may fare better (and certain states in the region may be able to make a more persuasive case than the United States, opening the door to a stronger collective self-defense case). But even then, the jus ad bellum requires that military action taken in self-defense be necessary and proportionate to the actual or imminent armed attack triggering the right to self-defense. The United States has once again adopted a more permissive view of this requirement than much of the international community. But even it has argued that military force must be evaluated in line with how it addresses the threat in question and should be pursued only after reasonably available alternatives are found to be unavailable. Yet Tuesday’s strike has no apparent relationship to thwarting acts of actual violence against the United States or U.S. nationals (or any other state). Moreover, Rubio has openly acknowledged that interdiction was an available option that Trump chose not to pursue in order to “send a message[.]” Hence, even under the permissive standards adopted by the United States, the Trump administration’s actions raise serious questions about compliance with the jus ad bellum.

Jus in Bello

The jus in bello, meanwhile, raises a separate set of legal questions regarding the conduct of hostilities that apply regardless of the legality of the Trump administration’s actions under the jus ad bellum. Among other requirements, the jus in bello requires that states using force as part of an armed conflict only directly target military objectives and specifically bars them from targeting civilians. As with the jus ad bellum, the United States adopts interpretations of the jus in bello that are, in many areas, more permissive than the standards adopted by other countries. But even under those standards, the Trump administration’s actions raise questions.

The Trump administration seems to maintain that all 11 individuals it killed were legitimate military targets on the grounds that they were members of Tren de Aragua, an organization “undertaking hostile actions” and “conducting irregular warfare” against the United States. But the legal standards generally applied by the United States don’t clearly support this conclusion. To qualify as hostile and thus targetable, non-state armed groups normally have to engage in or intend a concerted degree of violence against the United States rising to the level of a non-international armed conflict. Neither narcotics trafficking nor illegal migration clearly qualify and do not appear to have provided the basis for such a determination in the past. Nor does the actual violence Tren de Aragua is accused of having pursued come close to the level anticipated in U.S. guidelines, which underscores the need to distinguish non-international armed conflicts from “isolated and sporadic acts of violence.”

Thus far, the Trump administration has also declined to make clear how it “positively identified” the 11 killed individuals as members of Tren de Aragua. Existing U.S. standards apply both formal and functional tests to make this determination, which include such factors as whether individuals carry special insignia, follow the direction of organizational leaders, frequently engage in hostilities at its direction, or perform services similar to combat support roles to its combatants. Notably, simply associating or collaborating with a non-state armed group on activities unrelated to their conduct of hostilities does not itself deprive individuals of civilian status. This would seem to include narcotics trafficking, at least if one does not buy into the Trump administration’s novel argument that such trafficking itself constitutes hostilities. It would also include other activities, like migrant trafficking (or being trafficked as a migrant), that the Trump administration has nonetheless characterized as hostile and may seek to target.

While it has not to date, the Trump administration might argue in the alternative that narcotics trafficking is a revenue-generating activity that contributes to Tren de Aragua’s conduct of hostilities. Under past U.S. practice, this could make the activity itself a targetable military objective in at least certain circumstances, even if the individuals involved retained their protected civilian status. That said, premising the recent strike on this legal theory would raise an alternate set of questions regarding whether taking lethal action was necessary and proportional in light of the loss of civilian life—especially if interdiction was an available option, as Rubio has suggested.

International Human Rights Law

Of course, if Tren de Aragua is not engaged in hostilities with the United States, then the law of armed conflict may not be the appropriate framework for evaluating the legality of its actions in the first place. Much of the international community—which seems unlikely to buy into a war framing—is likely to instead view the Trump administration’s actions through the lens of international human rights law, which unequivocally prohibits such targeted killings except under extreme exigencies not applicable here. For its part, the United States has historically been cagey on whether its obligations under key international human rights treaties extend extraterritorially. But as Brian Finucane points out in his useful analysis of relevant legal issues at Just Security, relevant Defense Department guidance acknowledges that customary international law maintains a similar prohibition on murder and related offenses that applies in the context of overseas military activities.

None of this means that the U.S. strike is certain to result in a global uproar. Both Tren de Aragua and the Maduro regime are problematic actors that present genuine policy challenges, for both the United States and other states in the region. Few regional or international actors are likely eager to be perceived as coming to their defense by raising strong international legal objections, particularly in a way that is likely to earn the ire of the Trump administration and complicate their relationship with the United States. No doubt this helps explain the muted international response thus far.

But if the Trump administration uses this single strike as a model for a broader campaign—something Rubio has suggested it intends to do—then this calculus may shift. And even if it does not, persistent concerns over U.S. compliance with international law could complicate its international relationships and deter the sorts of multilateral cooperation that have been a long-standing pillar of U.S. efforts to combat narcotics trafficking and other criminal activities in the region.

Did the Strike Violate U.S. Criminal Laws?

The tension between the Trump administration’s actions and the United States’s traditional approach to the international law of armed conflict also has ramifications in another unlikely domain: U.S. federal criminal law.

Congress has enacted several statutes that make certain overseas violence with a unique nexus to the United States a federal crime. These include prohibitions on the murder of U.S. nationals in foreign jurisdictions (18 U.S.C. § 1119); murder by or against a U.S. national in places outside the jurisdiction of any nation (18 U.S.C. §§ 7 and 1111); conspiracy within the United States to murder persons outside the United States (18 U.S.C. § 956); and war crimes by U.S. nationals or service members (18 U.S.C. § 2441). On their face, several of these prohibitions seem potentially applicable to overseas U.S. military operations—including the strike pursued by the Trump administration.

Executive branch lawyers wrestled with several of these same statutes in 2010 when the Obama administration was considering a lethal strike on Anwar al-Aulaqi, a Yemen-based leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula who also happened to be a U.S. citizen. In a lengthy legal opinion, the Office of Legal Counsel concluded that none of the statutes in question prohibited al-Aulaqi’s killing. In their view, even where they do not expressly limit themselves to cases of “unlawful killing,” the murder and conspiracy statutes incorporate a well-established “public authority” exception that omits lawful governmental actions from their scope, including military actions. The war crimes statute, meanwhile, directly incorporates the definition of a “grave breach” from the Geneva Conventions, which does not apply to lawful military operations. Both exceptions applied to the anticipated military action against al-Aulaqi for essentially the same reason: because he was a lawful target under international law as traditionally applied by the United States.

Whether the same can confidently be said for the individuals targeted in the Trump administration’s recent attack is far from clear, for the reasons discussed above. If it cannot, then those involved in planning and executing such action may, under the executive branch’s own analysis, have acted contrary to federal criminal law. To be certain, various barriers—including the president’s substantial official immunity and other officials’ presumed reliance on his determinations—would likely complicate any effort at prosecution even if the Trump administration were willing to pursue it, which it undoubtedly is not. Trump could also issue pardons to make prosecution under any later administration impossible. Nonetheless, it remains an unsettling conclusion.

Notably, this conclusion may extend to foreign legal systems as well, many of which have similar exceptions to their criminal laws for legitimate acts of war. Particularly as some such states claim universal jurisdiction over certain human rights and international law violations, those involved in the attack may find themselves exposed to criminal liability overseas. Again, various legal and political factors—including sovereign immunity—are likely to complicate any actual prosecutorial efforts. But certain foreign officials may be more willing and able to try.

What Does This Mean for the President’s Article II Authority?

The conclusion that the recent strike appears to be in serious tension with traditional U.S. approaches to international law and U.S. federal criminal law is disconcerting in its own right. But it also has potential ramifications for the president’s legal authority to undertake such a strike in the first place.

In regard to international law, a number of legal scholars have argued that the president’s constitutional obligation to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” extends to U.S. treaty obligations, including the UN Charter. The executive branch has previously rejected this view, and the Trump administration almost certainly does the same. But for those who do not, the conclusion that the Trump administration’s actions may well violate international law—and the charter specifically—is likely to raise questions about his constitutional authority to undertake them.

Concluding that the president’s actions may run afoul of federal criminal statutes enacted by Congress raises other potential concerns. Article II of the Constitution does not expressly provide the president with broad authority to use military force. Instead, the executive branch has argued that this authority derives from a “historical gloss” that past practice has put on the president’s Article II authority as “Commander in Chief” and his possession of the “executive Power.” As described by the Supreme Court, such gloss arises from “systematic, unbroken, executive practice, long pursued to the knowledge of the Congress and never before questioned.” But if the president’s actions run contrary to long-standing criminal statutes—and the traditional practice of the executive branch in complying with the international law of armed conflict—can it truly be said that Congress has acquiesced in this way? At a minimum, potential incompatibility with federal criminal law raises questions as to whether the Trump administration has acted in a manner inconsistent with “the expressed or implied will of Congress.” Where this occurs, the legal framework that the Supreme Court traditionally applies to such questions warns that the president’s authority is “at its lowest ebb” and his actions must be “scrutinized with caution.” In short, violating a federal statute puts the president’s legal authority at its nadir.

To survive such scrutiny, the president generally must show that the actions he wishes to undertake are within his exclusive constitutional authority and thus not subject to congressional limitation. And perhaps President Trump will make this argument here by contending that the actions he took were the exact sorts of acts of national self-defense that are within his exclusive constitutional authority to pursue. Indeed, Rubio’s assertion that the president has “a right to eliminate immediate threats to the United States” arguably leans into such a framing. But any such argument would be a dramatic expansion of what has to date been a narrow and rarely invoked claim of authority. Perhaps more importantly, it would also be an extraordinary assertion of unbridled presidential war-making power, in an era when such claims have become the subject of bipartisan skepticism.

None of this amounts to dispositive evidence that President Trump acted outside his Article II authority in pursuing the strike on Tren de Aragua. Among other factors, the executive branch often receives an exceptional amount of deference on national security decisions, particularly in relation to the use of military force. Perhaps this will be enough for it to carry the day. But at a minimum, by targeting individuals whom the United States has traditionally viewed as civilians, the Trump administration has placed itself well outside the established practice of the executive branch. And doing so brings with it legal risks, including for the president’s constitutional authority.

Does Any of This Really Matter?

Those who follow domestic legal debates around the use of force may well be inured to many of these concerns. After all, many presidential uses of force under Article II have been criticized as unlawful, based on legal scholars’ individual assessments of the applicable laws. Yet challenges to the president’s authority almost never find their way before a federal court, and, when they do, federal judges have often resisted taking them up. This has left the executive branch free to continue to act on its own evolving views of the law, in spite of such criticisms.

Yet the Trump administration’s strike on Tren de Aragua is different. It risks transgressing a (moral, if not legal) line that many consider sacrosanct: that states should not target civilians with lethal force. Perhaps the Trump administration is correct that it remains on the right side of that line. But its arguments as to why this is the case go well beyond what the executive branch has previously asserted. Moreover, many of the legal arguments that the Trump administration has advanced in relation to narcotics trafficking might also extend to other, far more troubling uses of force that certain administration officials have reportedly raised—for example, the use of lethal force against unlawful migrants whose transport is facilitated by Tren de Aragua. In this sense, they may well prove controversial and generate political opposition, particularly in an era when members of (and voters in) both parties have grown wary of broad presidential claims of war-making authority.

Moreover, by arguably violating a federal statute, the Trump administration has increased the chances that such debates will cease to be strictly academic. Doing so arguably creates the sort of separation of powers dispute that federal courts (including the Supreme Court) have suggested they may be obligated to get involved in, even in the war powers context. Exactly how such a question could get before a federal judge in this case remains far from clear, but it’s happened before. And if it does, the Trump administration may not be able to count on the federal courts’ traditional reticence to engage on war powers matters to evade judicial scrutiny. As Justice Brett Kavanaugh himself once wrote, “[I]t is not likely a winning strategy … for a President to assume that he will be able to avoid judicial disapproval of wartime activities taken in contravention of a federal statute.”

These risks are likely limited so long as Tuesday’s strike remains a one-off and no revelations reveal it to be something other than what the Trump administration says it is. But if it becomes a model for a broader campaign, as Rubio has promised, the chances of the Trump administration’s potentially unlawful actions becoming a genuine point of political controversy—or triggering possible judicial review—will quickly increase.

This is why most presidential administrations are careful to work through legal arguments in support of their military actions and are prepared to defend them when pushed. The fact that the Trump administration does not appear to have done so here may yet be something they come to regret.

This article was made possible in part by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.