Lawfare Daily: U.S. Military Conducts Lethal Strike on Venezuelan ‘Drug Boat’

In a live conversation on Sept. 4, Lawfare Editor-in-Chief Benjamin Wittes sat down with Lawfare Senior Editor Scott R. Anderson and Professor of Law at Cardozo Law School Rebecca Ingber to discuss the U.S. strike on an alleged “drug boat” traveling from Venezuela, the president’s authority to use lethal force outside of war, and more.

To receive ad-free podcasts, become a Lawfare Material Supporter at www.patreon.com/lawfare. You can also support Lawfare by making a one-time donation at https://givebutter.com/lawfare-institute.

Click the button below to view a transcript of this podcast. Please note that the transcript was auto-generated and may contain errors.

Transcript

[Intro]

Rebecca Ingber: The

idea that we did not have effective control the U.S. military versus what is,

the equivalent of a fishing vessel, right, that we did not have effective

control over these circumstances sufficient that we could have done something

differently is, farcical. And so I, I think we're, I think they are creating

the textbook case for why international human rights law should apply to these

circumstances.

Benjamin Wittes: It's

the Lawfare Podcast. I'm Benjamin Wittes, editor-in-chief of Lawfare

with Lawfare Senior Editor Scott R. Anderson and professor of Law at

Cardoza Law School Rebecca Ingber.

Scott R. Anderson: Presidential

authority in this area is a little bit of a one-way ratchet. Once it does

something, it creates a precedent future presidents may rely on. And the way

you can chip away with that is really criticizing it and being very public

about the problems with it.

And so I do think there's value to that and reasons to keep

talking about it doesn't mean the president's gonna be stopped in this one case

or be able to account in this one case, very unlikely.

Benjamin Wittes:

Today we're talking about the U.S. strike on that alleged drug boat traveling

from Venezuela, the president's authority to use lethal force outside of armed

conflict, and more.

[Main Podcast]

Guys, I wanna start just with what we know about what happened.

Scott, get us started, a boat went boom in the Caribbean. What, what do we know

about what happened and why do people care?

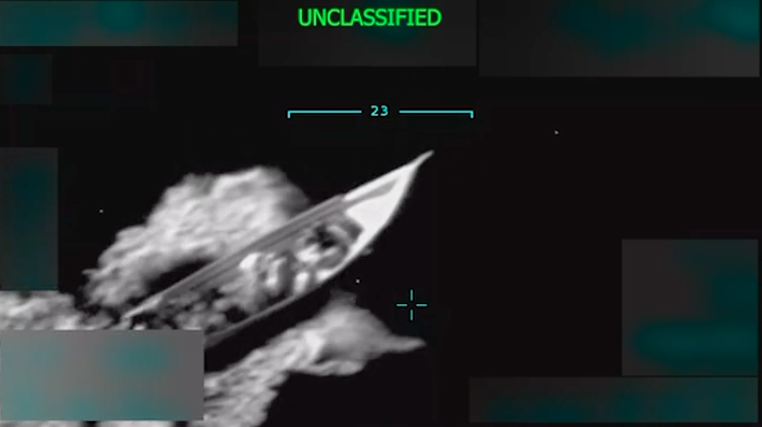

Scott R. Anderson: So

on Tuesday around midday, President Trump mentioned to a group of reporters in

the Oval Office for an unrelated event. We literally shot out a boat, a drug

carrying boat, just minutes ago, something to that effect. I think I'm actually

quoting the language as quoted in the relevant reporting.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio then tweeted out within moments

a tweet, essentially saying, as the president just confirmed, the U.S. military

has conducted a lethal strike to the Southern Caribbean against a drug vessel,

which had departed from Venezuela and was being operated by a designated narco-terrorist

organization.

And then a few hours later, we got a much more formal is not

quite right, but much more detailed description that obviously is copying and

pasting from some sort of official language on through social from President

Trump himself where he said U.S. military forces had conducted a kinetic strike

against quote unquote, positively identified Tren de Aragua narco-terrorists in

the SouthCom area of responsibility. That phrase is how you know this was

copied and pasted out of a Defense Department statement–meaning in the

Caribbean if you're wondering

He notes TdA is a designated foreign terrorist organization

operating under the control of Maduro, the head of Venezuela de facto, as was

not technically recognized by the U.S. government at the at the current moment

at least from the U.S. perspective, and noted that all 11 people were killed in

action.

No U.S. forces were harmed and noted that it was described as a

warning to anybody thinking about bringing drugs to the United States. We have

since gotten some follow-on comments from other folks in the administration. I

have not seen a War Powers Report yet, which we would normally expect within 48

hours. I will check while we're recording to see if it's gone up in the last

hour since the last time I checked, but I still haven't seen it.

But we have seen other statements that look a lot like they've

been segments or address sort of similar issues, but one that really jumps out

that I think is notable. Secretary Rubio said in follow on statements, we had

originally thought about interdicting the ship. But the president opted not to

send a message to Tren de Aragua and other smugglers, something that has

various potential legal ramifications as a force was evidently not a last

resort, but a first resort in this case.

Benjamin Wittes: And

was intended not for defensive purposes, but to send a message.

Scott R. Anderson:

Correct.

Benjamin Wittes:

Alright, so there are about a thousand issues that are raised by this very

brief account that Scott just gave us, and I wanna take them in order. But

before we do, I wanna just set up the conversation with a few background legal

points. Number one, is there any congressional authorization for the use of

force against any non-state Caribbean based actor that imports drugs into the

United States?

Rebecca Ingber: No,

there is not.

Benjamin Wittes:

Okay. Next question. Does designating something as a foreign terrorist

organization convey the authority to use force against it?

Rebecca Ingber: No,

it absolutely does not.

Scott R. Anderson:

No. I would say the one link between this is that when you designate an FTO or

an SDGT, you are making a finding that they threaten the security of U.S.

nationals and national security. So there is that nexus 'cause you would make a

similar finding if you're going to use force for self-defense purposes against

it, probably a more significant finding, but correlating them one-to-one.

And certainly there's no statutory link between the two,

between use of force and an FTO or SDGT designation, almost the opposite. It's

very clearly something Congress did not anticipate in the regime.

Rebecca Ingber: And I

just wanna jump in here because there's a lot of confusion about this and I

think rightly because the word terrorism gets thrown around, but these are

completely different standards, right? We have a standard, we have a legal

standard for when we can use force in self-defense, for example. And there's a

completely different legal standard for when we designate an FTO.

And there are lots of issues that might implicate national

security or might even suggest that there's national security threat, but that

does not have anything to, that might be relevant evidence toward the same

evidence we might use for making for meeting one standard might be relevant to

the other, but it is a very high bar for when we can use force and self-defense

and some simply posing a threat or being a national security issue is not, does

not meet it.

Benjamin Wittes: Okay,

last setup question. Is there a word both in the law and in common English

usage to describe killing people when it is not otherwise intentional killing

of people when it is not otherwise authorized by law.

Rebecca Ingber: Yeah.

I think we can safely call that murder.

Benjamin Wittes: Okay.

Scott R. Anderson:

That is the law professor. I'll defer to her on that.

Benjamin Wittes: Yeah

I'm just saying 'cause–

Rebecca Ingber: I

assume that's where you're going.

Benjamin Wittes: That

was, that was where I was going. I look at this and I say the stakes here are,

if you are not in the land in which some, by some way, this is authorized by

something other than the president wanting to do this. We have a word for that.

The default here is not that this is some benign activity that maybe presidents

can do some of the time.

Rebecca Ingber: Yeah,

I think that's clear. I think we can get into this later, but I think there is

some, there's some tension between the legal frameworks that the president

wants to invoke as a matter of domestic law and the legal frameworks he

probably wants to invoke as a matter of international law and domestic law work

differently on that score.

There are many states that would argue that if something is not

strictly prohibited as a matter of international law, they can undertake that

action, but our domestic system does not work that way. The president needs

affirmative authority in order to act, and he might be trying to claim wartime

authorities as a matter of domestic law to give him some kind of, to somehow

give some kind of political or even legal justification for his actions.

But as a matter of domestic law, he's not gonna want to claim

that because then he takes on a whole lot of prohibitions that are quite clear

and which this quite clearly violates.

Scott R. Anderson:

Just to spell out a little bit more specifically on the murder point. There are

obviously statutes barring murder in the United States and there are some very

specific statutes, varying types of extraterritorial murder.

It's actually not categorical 'cause U.S. doesn't have

jurisdiction over all things that happen overseas. But there are a variety of

ones that several, which I think arguably could or do apply in this particular

circumstance. The way the executive branch has argued in prior cases, and I

think there is a persuasive case for this, is that most murder statutes are

understood to incorporate an implicit exception for what's called public

authorities, when a U.S. official acts consistent with their lawful authority,

including in the context of armed conflicts that is not murder because it's

under this public authorities exception that is express in kind of the core

longstanding murder statute and implied in lots of other statutes that build on

that.

That's the conclusion the Obama administration reached in its

Office of Legal Counsel opinion regarding the targeted killing of Anwar

al-Awlaki a decade and a half ago now. It's shocking that's that long ago in my

mind. The thing that's complicated here is that analysis really hinge on the

fact that public authority exception applied because al-Awlaki was a lawfully

targetable individual under depending on how you read the opinion, 'cause it's

a little fuzzy on this, either the Law of Armed Conflict or U.S. practice as

informed by the Law of Armed Conflict.

And there's like a methodological, query as to which is the

right frame of restaurant reference. But they both reached the same outcome in

this case, which is that Anwar al-Awlaki was somebody who's clearly part of

Al-Qaeda, a group that the Obama administration felt we were in armed conflict

with and therefore it was targetable.

That's the conclusion the Trump administration wants us to draw

here that apparently if they lawyer this properly, somebody drew within the

administration. But it is a much harder case to make than it was in the al-Awlaki

context for reasons we can get into.

Benjamin Wittes:

Alright, so we're gonna get into all of that, but I wanna propose a very simple

mental rubric for people to think about this, and it's intentionally

simplistic.

And I would be interested in whether either of you think it's

in addition to being simplistic, wrong, but the basic way I would suggest

people think about this is the president has under certain limited

circumstances like unarmed conflict, the right to kill people, the authority to

kill people in the absence of a, some authorization, whether it's

constitutional or statutory and compliance with the law of armed conflict,

assuming that authorization exists, he doesn't have the authority to just go

around blowing up boats, and we would call that murder, whether or not the

murder is within the jurisdiction of the United States to contemplate.

Is that a fair, so if it's authorized, somehow he has the

authority to do it, if not, you have to ask the question whether it's murder.

Is that fair?

Scott R. Anderson: I

think so. I think I'm tracking this sort of framework. Yes, I, the key thing to

point to bear in mind though, is that these questions are interlaced and

interwoven and are really complicated way because the president's authority to

undertake a lot of these actions is premised on tacit congressional consent.

The president's argument as to why he has the authority to use

force in a variety of circumstances isn't just 'cause he's, it's not strictly

textual, it's just 'cause he is commander in chief. The executive branch has

always argued it's 'cause of that. And by the way, for the last 200 years,

we've taken actions like this and Congress hasn't objected and that has put a

gloss is the historical gloss, is the phrase on the constitutional text and says,

we can do this. But if this is the sort of thing that murder statutes have

prohibited for a long time–

Benjamin Wittes: Then

Congress hasn't ascend–

Scott R. Anderson:

Then it's a di- more harder question is saying, is this something congress has

consented to?

And the extraterritorial murder statutes are more recent of the

1990s. But then this raises the question does that mean Congress has prohibited

this generally? I if not historically has it taken affirmative action that

raises a separation of powers question saying, can Congress restrict this?

And it puts the executives authority to take this action in a

much more skeptical zone. Does the Youngstown category for three for

those keeping points at home. So it is really a much more complicated

interwoven question here. It's not so easy as saying, is this a crime? Does the

president have the authority to do this?

They're all related to each other, and this is operating on

that seam between international law, criminal law, and constitutional law that

we haven't really operated on before. It is really like the tip of the spear

for these questions, and that's what makes it such a complicated case to

dissect in my mind and why it raises so many very troubling questions.

Rebecca Ingber: I

would just add to that, that I, we, this has not, we have not seen a lot of

lawyering of this. It's actually doesn't happen all that often. And so the

reason the al-Awlaki opinion, the OLC, opinion from the Obama administration is

so important is because it's one of the very rare examples we have of the U.S.

government laying there ultimately, and in a somewhat unclassified form for us,

what the legal theory is.

And in that case, they had a lot of barriers to get through in

order to justify and on and suggest that there was a legal justification for

the president engaging in, in that case, a strike against someone who was a U.S.

citizen operating in another country, who was in the U.S. government's view, a

high level operative in an actual armed group who had sent operatives to the

United States in an attempt to rate.

He was, this is the individual who's behind the the Christmas

day or Christmas Eve underwear bomber. And so this is, these were high, this is

a high level operative engaged in an, as a high level operator as part of an

organized armed group in a conflict with the United States. And it was still a

very tough question that many people think was wrongly decided.

And the way that the OLC lawyers got through that question is

they had to address a number of statutory restrictions, constitutional

restrictions on the Use of force to target and kill people abroad, in addition

to the questions of whether or not the president had authority to do and the

way they got around all of that, as Scott pointed out, but I would characterize

it a little differently, is they basically assumed that there was this caveat

this exception for, to all of these rules for targeted killings that were

lawful under the laws of our, under the international laws of armed conflict.

And so the idea was that there was this international law exception because

international law recognized that states would engage in this context.

And so it's actually very important to know whether or not

international law recognizes that states are going to and have historically

engaged in this kind of killing abroad or killing on the high seas in order to

understand the president's domestic authorities. And if there is no precedent

for doing so, that is a very hard, hard justification to come up with.

Benjamin Wittes:

Alright, so there's a lot here. Let's unpack some of it. First of all, on the

question of authorization there's no doubt that there's no congressional

author, there's no statutory authority, relevant statutory authorization for the

use of force. That is, of course, different from in the al-Awlaki case where he

was alleged to be a senior operational Al-Qaeda leader, where there was a or at

least a senior leader of an associated force where there was a authorization.

So here in the absence of a congressional authorization, we're

necessarily using a theory of inherent presidential power. Scott, for those who

don't remember what is the standard for inherent presidential authority

according to the longstanding position of the executive branch? What is–leaving

aside whether that's the right standard or the wrong standard. Over time,

administrations of both parties have taken a fairly aggressive view of what the

inherent constitutional authority test is. What does it look like?

Scott R. Anderson:

Sure. It's worth noting some 20th century presidents, 21st century presidents

have argued for basically plenary authority on the part of the president, very

close to it. That's the early George W. Bush administration, the Truman

administration. But the contemporary view which is an articulation that dates

back to the 2011 Libya OLC opinion. But the logic of which really goes back, at

least to the Clinton administration, I have written and argued, it goes back

all the way to the Eisenhower administration, basically says there's two, or

depending on how you read it, three sort of prongs.

First, it's all contingent on insofar as Congress has not

specifically restricted this par authority. So it acknowledges there's a

possibility Congress might have some authority to restrict what the president

can do in this space. The president can reasonably conclude that a, it serves

sufficiently important national interests.

That is a fairly broad and fairly permissive and has been

interpreted increasingly permissively over the years standard. Jack Goldsmith

and Curtis Bradley very wrote a very useful piece on this maybe five or six

years ago for Lawfare that's worth checking out on that they documented

how that category has grown. It's not particularly restrictive.

Then B, the nature, scope, and duration of the anticipated

hostility, including escalation, the risk of the response cannot rise to the

level of a war for constitutional purposes that implicates the declare war

clause. That is a term of art that basically is saying, look, the Constitution

says Congress, not the president, has the authority to declare war that set

some substantive limit.

This is a concession that Truman administration, the George W.

Bush administration, did not make modern administrations, including the first

Trump administration have made it. And they've said, but only if nature's scope

and duration rises to that level where that level has never been clearly

defined.

Various administrations or people in administrations have

suggested the Korean War is the high watermark. William Renquist at one point

said it suggested Vietnam in May 1970 would've passed the threshold. So

something below that, but the usual understanding is that it entails a major,

significant extended armed conflict involving substantial loss of U.S. life. Not

something like this specifically, unless there's a serious risk of this

escalating to that sort of level.

Notably, I would say there's a tweak and a wrinkle to this as

well that came out in the first Trump administration, although it's based on

logic that dates back at least to the Ford administration, arguably earlier,

there is an idea that this framework aside, the president has some exclusive

constitutional authority in certain circum-, circumstances of national

self-defense, to take military force in a way that is not subject to declare

war clause limitations and not subject to statutory restrictions, exclusive to

the president.

That was referenced somewhat obliquely in the Soleimani 2020

Office of Legal Counsel Opinion. That's the closest formal acknowledgement I've

seen of it since discussions around the Mayaguez incident in 1975, but it's in

the background. If you talk to executive branch lawyers, it's always hanging

out there and that's one caveat or exception that maybe could apply here.

Although it's not clear to me, a hundred percent needs to from the Trump

administration's perspective. Does that sound right to you, Rebecca? Anything I

missed on that?

Rebecca Ingber: Yeah,

I think the one piece that I think that's all right. And the one piece that

I've always found interesting is that until recently, I think until the 2018

Syria OLC opinion, there had actually been a partisan divide in the way that

different lcs were dealing with when the president could use, of course, unilaterally

and Democrat lcs to call them that, although I think they would quibble with

that, a description, used this not war in the constitutional sense and really

fleshed it out, and it, and I think it started getting fleshed out.

I think it, I think you're right that it dates back to previous

administrations, but I think the first fleshing out an attempt to constrain its

use was in 1994, I believe, with Walter Dellinger opinion. And the, these

administrations were trying to lay out when the, in, in a, in an, in the, I

think in an attempt to constrain the president's use, which maybe they felt had

gotten out of hand, right?

Say, okay, the president's only gonna use force in those

instances that do not constitute war in the constitutional sense, and here's

how we're gonna lay that out and we're gonna have all these multiple factors.

And then over time, again, since 1994, I think that use has become expanded on

the other side.

Republicans have tied their use, I think more to self-defense

and those have sometimes been extremely expansive, such as the 2001 opinions

that are still on the books as far as I know, suggesting that the president

could do a lot in self-defense, including presumably launch a ground war.

But, ironically, in a sense that actually ties, I think more

closely back to what the framers actually had in mind when they thought the

president might use force unilaterally to quote unquote repel attacks on the

homeland. And if we were to reimport or reinvigorate that concept that the

president can only use force unilaterally in self-defense, that might help us a

lot here because it might feel like it, it doesn't sit well with us to suggest

that because this wasn't war in the constitutional sense, according to a long

line of lcs, the president can do whatever he wants here, but rather if we

were, if he were forced to tie it to self-defense, he would actually need to

make a clearer claim to self-defense. And I don't think that there would be one

here.

Benjamin Wittes:

Under international law, there is no question that he has to make a

self-defense argument, right? There's no, although it's, the boat isn't a

flagged ship, it's not a creature of Venezuela, presumably under the law of

armed conflict and other, probably under international human rights law, one

state just can't go around blowing up ships, right?

Rebecca Ingber:

That's a really, that's a much more complicated question. It feels like it

shouldn't be. It does feel like it shouldn't be, doesn't it? This is a textbook

case I think for why the longstanding U.S. position on international, on the

jurisdictional scope of, and the extraterritorial scope of international human

rights law is problematic because under the U.S. position, these treaties that

we've signed onto that were party to that would prohibit extra judicial

killing, for example, which this would be a prime example of do not.

And this is it's a little more complicated than this, but more

or less do not apply extra territorially, right? That they are jurisdictionally

bound and so they wouldn't under the U.S. longstanding position, those treaty

norms wouldn't necessarily apply to this context.

Now Brian Finucane actually at Just Security very helpfully

pointed out that the DOD operational law manual has noted that this kind of

murder in these kinds of circumstances would actually be a prohibition under

international, under customer international law. So that's quite helpful

because even if these treaty terms don't necessarily apply extra territorially

under the U.S. view.

Again, I say that because there are other states that would

have a disagreement with us over this. We've got this customary international

law norm that does apply. I will also say that it's not just the United States

that holds that view.

There have been a, a number of judicial opinions of

international tribunals that have not found that airstrikes, for example in

another territory would fall within various human rights treaties. There's,

it's complicated a little bit by this recent decision in Russia v. Ukraine,

but I think even that decision would not necessarily apply here. And so the

irony perhaps is that if this is a, if this is an a matter of the United States

government attempting self def, making a self-defense argument against

Venezuela or this hybrid state that they're claiming Venezuela is with these

gangs that actually would have a clear international law framework and it would

be unlawful because there was no armed attack.

And so this would not be a lawful exercise of self-defense in

response to an armed attack. It would also be unlawful if the law governing the

conduct of hostilities were to apply because these are not combatants that are

targetable under the law of armed conflict.

And so the more the U.S. government tries to claim a wartime

footing, the more they're actually implicating all of the international law

that quite clearly even under their own longstanding precedents would apply.

Scott wants to quibble with me.

Scott R. Anderson:

Okay. I do. Oh, I don't quibble with that on the international human rights treaty.

But I think there's an element of this from the jus ad bellum perspective

that comes in and actually compensates in a weird way in the U.S. practice

diagram 'cause United States also has a very low threshold for an armed attack

is to the point that violence against its nationals, it's treated as an armed

attack.

You look at Article 51 letters, as I understand it, feel free

to correct me back. Article 51 letters related to example of the ISIS

intervention in 2014 noted the threat to U.S. personnel and facilities in Iraq

as a basis for invoking military involvement, military personnel military

personnel.

Rebecca Ingber: Suppose

that's right, it's more complicated when we're talking about civilians. So

actually so yes a use of force under the U.S. view. The U.S. view has long been

that a use of force, a 2(4) use of force right, would constitute armed attack.

But there's still the question is this a 2(4) use of force, right? And that is

a complicated question because an attack on civilians is not necess, does not

necessarily implicate 2(4).

The more we claim that this is an attack on Venezuela, the

easier that analysis becomes, the more it implicates 2(4). But for it to

implicate that, and when I say 2(4), I'm talking about the UN Article two, Paragraph

four prohibition on the use of force, the cod, the ultimate codification of the

prohibition on the use of force. This is primarily a state to state

prohibition, right? States can't use force against one another and states can't

use force in their international relations against the territorial integrity of

another states. So they can't use force on another state's territory. They

can't use it against the political independence of another state.

So like killing their, the other state's leader for example, or

in other ways, against the purposes of the United Nations.

Benjamin Wittes: So

you think the best argument for the United States here would be nothing to do

with war? It was just a boat, civilian boat, and we targeted because we wanted

to send a message. Nothing to do with the with the state of Venezuela. Nothing

to do with a hybrid state. Nothing to do with the law of armed conflict. We

just blew it up because rah, that's actually the best international law.

Rebecca Ingber: I

think that if I were advising, if I were advising the United States, I would

say if you want these international tribunals who are up until this point,

taken on good faith, that when states engage in airstrikes, they should not be

governed by international humanitarian law.

If you wanna give them the best reason that they should

intervene, this is it. The idea that we do not have effective control the U.S.

military, they versus what is, the equivalent of a fishing vessel, right? That

we did not have effective control over these circumstances sufficient that we

could have done something differently is, farcical. And so I, I think we're, I

think they are creating the textbook case for why international human rights

law should apply to these circumstances.

Scott R. Anderson:

Just, but one specific qualm about this specific case. Trump has waived this

argument because, what did Trump say in his initial statement? This is Tren de

Aragua acting at the direction of Nicolás Maduro.

Now you can ask whether where the exact line is between where,

how far it actually extends between, is this the personnel of the state? Maybe

'cause they're not uniformed, maybe 'cause they're informal doesn't rise to

that level. I, but I think that is a, i in this case, the president is

operating in somewhat extent against his own interest potentially, if this was

where the direction you wanted to rely on. He is invoking a self-defense

argument in justifying this, I believe.

Rebecca Ingber: I

agree with you. The more that the president tries to put this in more time

framing, as I keep saying the more we're on a much clearer a much we're

invoking much clearer prohibitions that the U.S. government has long accepted

and that have always been part of international law.

And I, I will also say to that the problem there though, again

so of course Venezuela has not necessarily accepted the narrative. And what if

Venezuela were to consent? We've got these we've got states who are out there

saying, suggesting that they welcome U.S. intervention, right? If a state

consents that, that gets rid of our two four issue. And so we're still left

with the possibility that, if we argue international human rights law does not

apply. There is no law. I think that clearly cannot be the case, yeah.

Benjamin Wittes: So I

wanna propose yet another possible avenue, which is to say, okay, yes it is. I

guess this works better for domestic law purposes. But you say we're not gonna

make a self-defense argument, but we're gonna make the argument that was, that

closely parallels the constitutional law argument that Scott just laid out,

which is, we've got Venezuela, the government, and in cooperation with these

gangs that are infiltrating people and drugs into our shore, we're not gonna

tolerate it anymore.

And by the way, they are unable or unwilling 'cause we like

importing bullshit. Doctrines from other areas they're unable or unwilling to

do anything about it. We've raised it with them a thousand times. And so any

Venezuelan boat carrying drugs or people that illegally approaches our sure

we're gonna treat as an international attack. I take it that argument works a

little bit better as a domestic con law argument than as an international law

argument.

Rebecca Ingber: So

Scott is the, has canvased all the entire history of how the U.S. government

has handled the constitutional argument. But I will say that it depends on what

is the standard we're using.

If the standard we're using is not war in a constitutional

sense, then on, at least for the authority piece, again, we're not talking

about the murder statutes, but just for the authorities piece that might, that

might be enough to get you there. But I would again, argue that all of our

domestic authorities and to bring back in the federal statutes the way that,

that the U.S. government has historically gotten around domestic law

constraints on the use of force against individuals has been to argue that they

are lawful as a matter of international law and as a matter of international

law that just doesn't hold water, there has to be an actual armed attack or an

imminent armed attack on the United States and an armed attack has to, has to

mean something more than just we don't the fact that they're smuggling drugs

into the country.

Benjamin Wittes: Alright,

so Scott. Let's consider this from the point of view of lawyering within the

administration. We've got a prohibitive international law problem. We've got a

dicey domestic constitutional law problem, and we've got a variety of criminal

statutes that may or may not apply depending on how you parse a bunch of

things. How does this end up happening? SouthCom has a lot of lawyers.

Scott R. Anderson:

Yes, indeed they do. The jus ad bellum part of this, my understanding in

general, executive branch practice is going to be much more decided in the

White House in consultation with lawyers, with executive branch lawyers. But

DOD lawyers, people at SouthCom be more focused on the Use in bellow

considerations, meaning about the actual conduct of the hostilities as opposed

to the legitimacy of the hostilities, of themselves, the decision to resort to the

use of force.

That's worth just bifurcating exactly what lawyers will be

looking at this. And who would be thinking this over you. Look, I think your,

the argument that they've made I don't know what's the best one, but it's

certainly the argument they appear to be leaning towards, although I haven't

seen, again, full formal confirmation you'd have to pull together from snippets

we're seeing is that Tren de Aragua is engaged in hostilities with the United

States.

It is at a minimum, a non-state armed group. Maybe it's even an

outgrowth of the Venezuelan state that's, they're a little wishy-washy on,

they're engaged in hostilities against the United States. The basis for these

hostilities, and this is one of the big questions under national law, I think

probably the biggest problem in all of this is that it is based on narcotics

trafficking, illegal immigration, and some sporadic criminal violence.

But all that summed up together, the Trump administration is

saying this amounts to hostilities with the United States. They’re a non-state

armed group. And then these 11 individuals, they say they've positively

identified as members of TdA. So because this is a non-state armed group

engaged in hostilities with the United States, and these all are members of

that group that makes them all individually targetable.

You could see other arguments as well, like maybe they would

say this is an non-state armed group. And they are using, narcotics as a,

commercially, a resource for supporting their activities. So we could target

the narcotics and maybe a civilians were killed. It'd be collateral damage the

same way we used to target the Islamic State operating oil facilities in parts

of Syria. That's an alternative argument. I haven't seen them roll that out

yet.

But it, I think stands out as a possibility because the first

direct targeting the ability that all of these people are members of TdA, I

think runs into some problems potentially, but the key argument that appears to

be what they've queued up and they're saying, look, it's the same as if we were

attacking members of al-Qaeda.

We've attacked members of al-Qaeda regularly. We can attack

these people. The problem with that is, is there really hostilities between TdA

and the United States? Is it a non-state armed group or the way we think about

that's actually like kinda a another variable, although maybe it's you, there's

a more colorable case to be made there.

And then how confident are we, these 11 individuals, were

members supposed to make them targetable. If you are a civilian and doing

civilian things, and that's all we really know about these guys, they're on a

boat running drugs, that's a civilian thing, even if it is not a, even if it's

criminal and maybe objectionable.

Is it that they were all known to be members like in the

command chain of Tren de Aragua? They don't wear uniforms. Presumably they're

not wearing uniforms or any sort of in, in insig-, insignia. Is it that they

were taking commands? These are the kind of multi-variable factors that are

usually used to determine membership in a non-state armed group.

It's a pretty diverse and loose set of analysis, but not many

prongs of it. You see a lot of prongs of it that haven't clearly been shown

here. Now there's more evidence the DOD has, of course, internally, maybe

they're very confident. Oh, yeah all of these guys are full on in the command

chain of Tren de Aragua whatever that looks like.

But it certainly raises that, certainly a question worth

probing is saying how confident are we at this assessment that all 11 of these

people were individually targetable?

Rebecca Ingber: Yeah.

And I'd add to that though, that all of that case law that was developed over

the last 25 years involving extending, quote unquote traditional law of armed

conflict authorities to not to non-state actors was extremely controversial

when it happened. But it was all happening in the context of a congressionally

authorized armed conflict with this non-state actor that had attacked the

homeland and killed thousands of people.

Benjamin Wittes: And

in the context of ongoing operations, al-Awlaki was found to be rightly or

wrongly, and I think rightly, continuously planning additional operations.

Rebecca Ingber: Yeah,

I think that's a good addition.

Benjamin Wittes:

Alright. I wanna add. So I was one of the few people publicly willing to defend

the al-Awlaki strike and the reasoning behind it. And when that memo came out,

which was brought out through litigation with the ACLU, on Lawfare was I

think its principle intellectual defender.

I would never defend this. It seems to me the three basic

preconditions that made the al-Awlaki strike defensible are none of them

obviously present here. So the al-Awlaki memo was based on three facts, right?

He's a senior operational leader of al-Qaeda, or an associated force in this

case, associated force al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. His capture is not

feasible and his targeting would otherwise be consistent with the law of armed conflict.

Here, they're not senior operational leaders of somebody

against whom we've designated somebody that we've auth, Congress has authorized

the use of force. Their capture by Rubio's own admission is imminently

feasible. Rubio says we could have stopped it, but we decided to send a

message. In other words, the point was not to prevent some imminent

catastrophe. The point was messaging.

And number three, their targeting would be consistent with the

laws of war. Only if see previous conversation, you can actually treat Tren de

Aragua as a armed group that's engaged in hostilities against the United

States. Scott, walk me through how, and I say this as somebody who like, I was

fine with the al-Awlaki strike and I'm like, I'm really not fine with this.

Walk me through how the al-Awlaki strike is supposed to get us around. What

seems to me the obvious illegality of this?

Scott R. Anderson:

I'm not sure it does. I'm not sure you gonna lean too heavily on that because

it's actually not a great precedent for them on a few different fronts.

The one big difference is worth noting is that al-Awlaki was a U.S.

citizen and to our knowledge, none of these individuals are U.S. citizens. So

that brings into play a constitutional element of this. The OLC is very

concerned in its analysis of the al-Awlaki operation, are we comporting with

due process rights and other rights that al-Awlaki has by virtue being U.S.

citizen and particularly the force as a last resort was part of that analysis.

There are also parts of the law of armed conflict that says you

really should turn to force as a last resort or in the formulation of the

United States, at least in the jus ad bellum context, you should explore

reasonably available alternatives before just resorting to the use of force.

They don't necessarily say it has to be a last resort, but regardless, it's

still in play there.

But that was part of the reason that was such a big focus. So

that part, at least the constitutional elements of it, not as squarely in play

in this case, unless one of these people is an U.S. citizen, and I don't think

we can entirely rule out that possibility. But without advanced knowledge of

that, it doesn't necessarily query whether it raises the same questions and

deliberately targeting a U.S. citizen with knowledge that person's a U.S.

citizen.

I think arguably it doesn't, although I'm not, it's still

obviously something you have to consider. The question about the applicability

of and compliance with the law of armed conflict that really, at least in that

analysis comes back to the public authority exception of those criminal

statutes.

They were worried, I think, not just about criminal liability,

but also about the implications of if we're doing something that Congress has

expressly prohibited, can we really argue? Congress has tacitly consented to us

doing this as part of our assessment of the president, having the authority

under Article two to take these sorts of steps and they walk through a number

of criminal statutes, one of which prohibits conspiracy to kill people or

damage property overseas, one of which bars the killing of U.S. citizens

overseas again, 'cause it's al-Awlaki.

A couple of other criminal provisions many of which are may

apply here or do apply here. And there are a couple other ones that might apply

here as well. I walked through them and says, hey, okay, all of these seem to

incorporate this public authority exception that we well established in the

murder context.

All of these are basically importing the murder statute and

just adapting it to different circumstances and therefore it still applies to

all of them. But in doing so, it really did look at, again, traditional U.S.

practice as informed by the international law of armed conflict saying, can we

say this person was a legitimate, lawful targetable, and that is how far the

public authority exception went.

If that breaks down, I think it creates a big open question

that even if we take the out lock logic on its face, assume that a court would

agree with the executive branch on that assessment. I think it's a reasonably

good analysis. Then that doesn't necessarily hold, in this case, if that law of

armed conflict breaks down or if you're less confident in it, and I think you

have to be a lot less confident in it because again, this concept of

hostilities that the Trump administration is relying on that legal, immigration,

narcotics trafficking, and sporadic criminal violence rises to level

hostilities making this a non-state armed group with which we're in an armed

conflict with that is a real stretch of even the very permissive standards

United States has employed in the past. I think.

Rebecca Ingber: I

think the, I agree, I think the standard is not necessarily the best precedent

either way. I do think there is, there are precedents.

The use of force itself has not gotten, has not really been

litigated on the merits. And it has not actually, there, there's not a lot of

information we have about the U.S. positions. I think the best place to look

maybe actually, and by analogy might if they're going to think about this as a

law of armed conflict framework would be the Guantanamo detention cases.

And there again, we see the court grappling with trying to

apply old law to novel circumstances. If we're talking, if we're talking about

a non-state, state actor and whether or not there can be an armed conflict

between them, that is the place to look for the, the U.S. grappling with that,

and the courts leaned heavily on both.

The fact, and this goes back to Hamdi also in the

Supreme Court, the courts leaned heavily on the fact that this was a

congressionally authorized armed conflict in which there were ongoing

hostilities that actually looked a lot like traditional armed conflicts. They,

the court in Hamdi said that hostilities continue in Afghanistan and if

they cease to do this understanding will unravel.

And so there's nothing that looks like that here. And so the

suggestion that we should take what was already a stretch then but was accepted

generally by Congress and the courts, because A, we had actually been attacked,

and B, there were actual real hostilities ongoing that looked much more like

traditional conflicts that we should take that stretch and then apply it to a

context in which all we've got is basically pretext, right?

The president throwing around words. I don't think we should

try to credit this. I don't think we suggest that there's any real legal

argument here.

Benjamin Wittes:

Alright, so I wanna come back to that question 'cause it raises an interesting

litigation question. But before we do, I wanna talk about some of these murder

statutes, Scott has mentioned a couple of them. I wanna mention another one,

which is murder within the special maritime and territorial jurisdiction of the

United States, 18 U.S.C. 1111 which says simply whoever within the special

maritime and territorial jurisdiction of the United States is guilty of murder

in the first degree shall be punished, et cetera, whoever's guilty of murder in

the second degree shall be punished.

The special maritime jurisdiction of the United States includes

under 18 U.S.C. 7, any murder committed, any or any crime committed in a place

where nobody else has jurisdiction by or against a U.S. citizen. And so my

question, Scott, is why shouldn't I look at this and say, okay, maybe if

Congress passes an authorization to use force against Tren de Aragua, that

overrides 18 U.S.C. 1111 and the jurisdictional provisions and creates an al-Awlaki

like exception.

But until then I look at this and I say, Congress has spoken on

the question of whether you are allowed to blow up that boat in back of me. And

it says, if you kill somebody blowing up that boat and it happens to be an

American citizen, or you happen to be an American citizen you're guilty of

murder. What am I missing here?

Scott R. Anderson: So

the analysis here again, goes back to that public authority exception, at least

if you follow the line of analysis in the al-Awlaki opinion. But I do think

it's the most reasonable one here, which is that, look, if you were to follow

this, then you would never have any armed conflict that would not be

prosecutable for murder the United States could pursue in international waters.

Benjamin Wittes: And

we have had, ex, except if you had an authorization to use force, and Congress

says, okay, the Brookings Institution is such a dangerous institution that

we're authorizing the use of force against it then. The president isn't covered

by that statute at that point.

Scott R. Anderson: Perhaps

the executive branch as and Becca probably knows this better than I do, as she

was a little more, I was in college when a lot of this stuff was happening. But

the–

Rebecca Ingber: Thanks Scott.

Scott Anderson: Sorry, just because I know you were, I

knew, I know when you worked at State Department a few years ahead of me and I

just missed it.

Rebecca Ingber:

You're gonna go somewhere else with that. No. It's old.

Scott R. Anderson: Apologies.

Becca's old gee. No. But–

Rebecca Ingber: Children,

remember this just three years.

Scott R. Anderson: This

book was a little more alive before I got into government. The argument that

the Bush administration did make very early on that the a first they argued the

presidentials and exclusive pre constitutional authority preempt a bunch of

statutory restrictions. Then there were a bunch of efforts to ar, argue that

the AUMF displaces a ton of statutory limits.

Those arguments were not entirely, but mostly losers. So that

would not be the best argument. The Obama administration for that reason didn't

rely on that. Now Locky case, they certainly could have, they could have said,

and maybe it actually is in the big parts of the Al-Awlaki opinion that have

been redacted and aren't public totally possible.

But they could have said, oh, we think the AUMF just superseded

murder statutes. We don't have to worry about that. They chose not to. They

thought that was at least not a winner in the parts of the argument they

pursued. Instead they argued the alternative, which is useful when you're also

contemplating potentially taking action under the Article Two authority.

And presidents have done that historically, international

waters without statutory authorization in other cases not a ton of them, but it

has come up in, a handful of cases. In this case, they look through the public

authority exception, which you actually don't even need to implicitly read into

one 11 like you do in the other murder statutes.

I should now al-Awlaki 'cause it says specifically murders, the

unlawful killing of a human being. So that unlawful killing, they have

interpreted and they've got reasonably good legislative history in court cases,

supporting it as saying, Hey look, if you have somebody doing this for among

other exception, a public authority reason, it does not reach that sort of

reason.

And again, that public authority, the scope of that ties back

to is this a lawful target under how the United States has traditionally fought

wars, which is primarily. Informed by the law of armed conflict, although, you

could see it, maybe there's a delta between those two in some cases.

Rebecca Ingber: But

the AUMF is not irrelevant to that analysis. The, I the argument was this is a

a lawful targeting under the law of armed conflict in a congressionally

authorized armed conflict, which was important, especially in that case, given

that it was a conflict with a non-state actor where there was a lot of, at the

time, there was a lot of controversy over whether you could even have an armed

conflict between a state and a non-state actor, extra territorially.

And I just wanna point out that, if you didn't have that aspect

of it if the president were to target and kill, a member of another state's

head of state head of state from another state, that would create certainly an

armed conflict between the two states. But that wouldn't necessarily be enough

to, to get us out of a, the public authority exception, if there is one to

those murder statutes or the, for example, the EO on the assassination ban,

right? The assassination ban was clearly intended to encompass those kinds of

circumstances. And that was also the way, the way that all memorandum got

around the EO prohibiting assassinations, the executive order right on the

assassination ban was also through a public authority exception.

And so clearly it can't be enough that the president is acting

through in an armed conflict. It also, there, there has to be something else

more. And I think that in that case, in both in the OLC opinion and in the

other very limited law that we have to go judicial opinions and other things

that we have to go on, the fact that it's a congressionally authorized armed

conflict and that hostilities are actually undergoing and that there's a factual

analysis that's relevant to that is all part of the mix.

Benjamin Wittes: I

think it has to be,

Scott R. Anderson: I

don't think it actually is part of the public author's analysis. Maybe not

expressly, it's certainly part of the overall opinion, but the whole idea of

the public authority analysis is based on the unlawful killing language. So

interpreting you have to say, is there legal authority for this?

Rebecca Ingber:

What's an unlawful authority?

Scott R. Anderson:

Yeah. But I don't think they would be, I don't think they were saying that the

only lawful authority for this is statutory.

Benjamin Wittes: But

I but I wanna suggest, and I wanna bring in the fifth circuit's opinion here in

the Alien Enemies Act case from yesterday, because, so it's notionally a

completely unrelated issue, right? The, but–

Rebecca Ingber: It's

not actually, but it's ultimately a very similar question, which is a highly related

issue.

Benjamin Wittes: When

the Alien Enemies Act says an invasion or declared war, or predatory incursion,

can you reconcile that language with whatever the piddly stuff that Tren de

Aragua is up to, which is solidly in the criminal vein.

And it's, granted, it's awful, but it's not unarmed incursion,

right? And for in, in exactly the same way you look at this and you say

whatever this stuff is, it's not military engagement of that sort. And so what

could get you over that hurdle? One thing is Congress saying we're authorizing

force against it. Another thing could be an attack of the scale that you would

say, okay. We're clearly in some military conflict now.

Rebecca Ingber: I

guess I'm somewhere between you two, right? I'm saying it has to be both in a

way. I, I don't think that, I don't think that an AUMF alone would necessarily

get you over that hurdle, right?

You can imagine Congress authorizing a lot of things these

days. I think that the public authority exception that Scott's talking about, I

think he's absolutely right that the law of armed conflict that this was lawful

under the law of armed conflict, was extremely relevant. It was in fact, the

main point that the OLC memorandum is making.

I just mean that I think it was, that it was relevant to that

analysis, that it was in the context of a congressionally authorized actual

armed conflict, right? We could imagine a slippery slope where if we said it

doesn't have to be congressionally authorized, as long as it's, as long as it's

lawful under the laws of armed conflict.

We can imagine a scenario in which this president therefore

says, okay, then I have domestic authority to start an armed conflict. We can

imagine that being a dangerous slippery slope that we wouldn't have necessarily

had to grapple with under prior presidencies.

Benjamin Wittes:

Alright, before we close, I wanna ask the question that I think is on a lot of

listeners' minds right now, which is this a law school hypothetical or is this

a question that there is actually any mechanism to adjudicate Normally the

mechanism that you would use to adjudicate something like this would be either

a wrongful death suit.

There's probably a jurisdictional barrier to that. See the Al-Awlaki

case, you could also imagine a subsequent administration trying to prosecute

this and dealing with it that way. The president, of course, would be immune,

but the secretary of defense would not, and anybody down the chain would not.

So number one, Scott. First do you see any mechanism by which

this comes to be adjudicated in any useful fashion? And number two, if not, is

there any reason to discuss it? Other than that, it's interesting and

appalling, like what's the value of the conversation?

Scott R. Anderson: I

think it is unlikely to become the subject of litigation, nmot entirely

impossible, but unlikely. Look, in theory, we have seen civil claims be brought

about U.S. military action overseas. Remember, there is a longstanding decade

long litigation that found its way all the way to the D.C. circuit about the

attacks against a medical facility in Sudan by the Clinton administration on

the basis that was manufacturing biological weapons and a claim for damages

arising out of that.

That's possible in this case, and I will say, I think in this

case, the usual barrier to adjudication most of these cases is because courts

are. Hesitant to touch any of this with a 10 foot pole, in part because there

is not a clear conflict between the political branches. That is the line we see

in courts, say over and over again since the Vietnam era.

And even some cases arguably before that. But the logic

basically being, look, if there's no clear conflict between the political

branches, we're not really gonna get in a fight over this here. There is a

little bit more of a conflict. There is in some of these cases because there is

this tension with the murder statutes.

Again, that is a real separation of power's problem for the

administration. In contemplating this, if you can draw a clear conflict between

these statutes and what the administration has done, it both raises questions

about the president's substan substantive authority, and it also puts itself in

this category of a clear conflict of the political branches.

That is the circumstances where even this court, or at least an

earlier version of the Roberts Court in 2012 said, yeah, that's the exact sort

of circumstances where the Supreme Court has an obligation to intervene. Prior,

other judges, prior courts may have viewed that as a political question,

doctrine sort of thing.

This court pretty clearly said that sort of thing isn't a

political question doctrine, at least that's how I read that opinion. Some

people read it a little more narrowly, so in those sorts of circumstances, I

think there's some chance of that, but it doesn't need to go to court for this

to matter. We evaluate as voters as citizens as people who speak to Congress,

who can take more affirmative action on these things. We evaluate the

president's actions. We weigh it and say, do we think this is lawful? Do we

think this is colorable lawful, or incredibly lawful?

And in this case, I think there's value to saying, hey, there's

actually some real questions raised by this. It's important both for informing Congress,

important for informing us and our views of the administration potential future

action by Congress and for the legacy of this sort of action in terms of

potentially expanding the scope of presidential action moving forward.

Presidential authority in this area is a little bit of a one-way ratchet.

Once it does something, it creates a precedent, future

precedents may rely on. And the way you can chip away with that is really criticizing

it and being very public about the problems with it. And so I do think there's

value to that and reasons to keep talking about it doesn't mean the president's

gonna be stopped in this one case or be held to account in this one case, very

unlikely. May it make it less likely that this will become the model for a

broader campaign as the president has strongly implied?

I think it might probably marginal, but I think it might make

some impact in that regard because it suggests there's heightened legal risk

and heightened associated political risk. And that's why people pay people like

Becca and me and you, Ben, the big bucks that we make to keep having these same

arguments over and over again. Not me. This argument's a little, I'm not

licensed than most practice.

Benjamin Wittes:

Beck, what do you think? Is there any mechanism by which this gets adjudicated?

Rebecca Ingber: Yeah,

I, so I agree entirely with Scott here. I as an international lawyer primarily,

although do a fair amount of constitutional war powers from time to time, I am

regularly facing the the argument that many make that international law is not

really law. That if there's no clear enforcement mechanism, it doesn't matter,

et cetera.

And I tend to be of the unpopular view in these circles that

criminal law itself is rarely the best way to think about how public law gets

enforced or how it should be enforced. I think historically it has not been, it

has never been the basis on which public actors care about or abide by law. I

think that's true as a matter of domestic law.

I think that's also true as a matter of international law. And

in fact, I think the fact that criminal law has. In many people's views failed

them. It failed to address the political problems that were the Donald Trump

presidency. It failed to address international problems when the ICC has not

been able to actually hold people accountable.

That has led, I think to, to nihilism on the part of many in

the public about what inter, what law, what international, what public law

really means. It doesn't actually mean anything if we can't hold people account

through criminal processes that we're used to from watching tv. And the reality

is that public law does not tend to play out primarily in the courts.

There's an interactive dance between all sorts of actors if

it's international law, between states and various fora in which they operate.

If it's domestic public law, it's between Congress and the president and the

courts and the public, the voting public. And so I think Scott's exactly right

on this, that the voting public.

Whether they either care or they don't care. PE So there is no

overarching enforcement mechanism for domestic public law, just like there

isn't for international law. And that's suddenly becoming abundantly clear to

people. But it will matter. There's a reason that people continue to have these

conversations.

There's a reason to, if anyone is watching right now, there's a

reason you're watching, right? You, there's a reason you care about what the

law says. People tend to talk about law because they believe there is some

value to having a neutral set of principles under which we're operating. And

it's not just about whether I like this guy or not.

This is my president. This is the guy I voted for. So what he

says goes, they want to be able to talk in neutral principles. There's a reason

people care about law and. The public law system requires faith. It requires

buy-in from the public. If people care about law, about whether or not the

president is abiding by law by these neutral principles that we've established

before this particular action, and before this president was in office, then it

will continue to matter.

And if everyone stops caring about it, then they're right? The

nihilists will win. It will. It will cease to matter.

Benjamin Wittes: I

just wanna pause it. The mechanism by which I think this is likely to become

adjudicate relatively quickly, which is that the likelihood that one of 11

people on that boat was an American citizen is pretty high judging from the way

that gangs operate in the United States.

And I think we're gonna find the more we find out about that

boat by the way, when you're crowding a lot of drugs into a boat, you don't

carry a crew of 11. You carry a crew small enough so that you can fit more

drugs on a boat. We're gonna learn a lot more about that boat and none of it is

gonna be consistent with the story that we heard on the first day.

And somebody is going to have a case that is going to turn out

to be litigable. That is my guess. We're gonna leave it there. Rebecca Ingber,

it is great to see you. It's been too long. Come back early and often to the Lawfare

Podcast. Scott R. Anderson. Thank you both for joining us today.

Rebecca Ingber:

Thanks, Ben.

Benjamin Wittes: The Lawfare Podcast is produced

in cooperation with the Brookings Institution. You can get ad free versions of

this and other Lawfare podcasts by becoming a Lawfare material

supporter. Through our website, lawfare media.org/support, you'll also get

access to special events and other content available only to our supporters.

Please rate and review us wherever you get your podcasts, and

look out for our other podcast offerings, including Rational Security,

Allies, and Escalation, our latest Lawfare Presents podcast

series on the war in Ukraine. Check out our written work at lawfaremedia.org.

The podcast is edited by Jen Patja. Our theme song is from ALIBI music, as

always. Thank you for listening