“Anna, Lindsey Halligan Here.”

.jpg?sfvrsn=8253205e_7)

Watch Anna Bower discuss this article with Lawfare Editor-in-Chief Benjamin Wittes on Lawfare's YouTube here.

It was 1:20 p.m. on the afternoon of Saturday, Oct. 11. I was lounging in my pajamas, idly scrolling through Netflix, having spent the morning reading news stories, occasionally tweeting, and watching TV. It was a rare day off.

Then my phone lit up with a notification. I glanced down at the message.

“Anna, Lindsey Halligan here,” it began.

Lindsey Halligan—the top prosecutor in the Eastern District of Virginia—was texting me. As it turned out, she was texting me about a criminal case she is pursuing against one of the president’s perceived political enemies: New York Attorney General Letitia James.

So began my two-day text correspondence with the woman President Donald Trump had installed, in no small part, to bring the very prosecution she was now discussing with me by text message.

Over the next 33 hours, Halligan texted me again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

Through the whole of our correspondence, however, there is something Halligan never said: She never said a word suggesting that she was not “on the record.”

It is not uncommon for federal prosecutors to communicate with the press, both through formal channels and sometimes informally. My exchange with Halligan, however, was highly unusual in a number of respects. She initiated a conversation with me, a reporter she barely knew, to discuss an ongoing prosecution that she is personally handling. She mostly criticized my reporting—or, more precisely, my summary of someone else’s reporting. But several of her messages contained language that touched on grand jury matters, even as she insisted that she could not reveal such information, which is protected from disclosure by prosecutors under federal law.

As a legal journalist covering the Justice Department, I had never encountered anything quite like my exchange with Halligan. Neither had my editor. Over the last several days, he and I spoke with multiple former federal officials and journalists who cover the justice system. None could recall a similar instance in which a sitting U.S. attorney reached out to chastise a reporter about matters concerning grand jury testimony in an active case.

Justice Department spokeswoman Natalie Baldassarre confirmed the authenticity of the texts at 4:34 p.m. today, responding to my questions about the exchange with a statement that reads in its entirety:

You clearly didn’t get the response you wanted—which was information handed over to you without having to dig into the facts of the case to craft a truthful story—so you thought you’d “tattletale” to main justice. Lindsay [sic] Halligan was attempting to point you to facts, not gossip, but when clarifying that she would adhere to the rule of the law and not disclose Grand Jury information, you threaten to leak an entire conversation. Good luck ever getting anyone to talk to you when you publish their texts.

After I reached out to the department for comment on Halligan’s texts, Halligan texted me yet again, for the first time in several days, insisting that our entire correspondence had been off the record. Our full exchange, linked below, allows readers to make their own judgments on that question.

***

As with many Trumpworld stories, this one began with someone getting sacked. That someone was Erik Siebert, Halligan’s predecessor as the U.S. Attorney in eastern Virginia, who was removed—or forced to resign—last month.

According to multiple reports, Siebert had raised doubts that the evidence was strong enough to pursue criminal charges against two of President Trump’s longtime adversaries: New York Attorney General Letitia James, who won a civil fraud verdict against the Trump Organization, and former FBI Director James Comey, whom Trump had fired during his first term in office and had long blamed for the so-called “Russiagate” investigation. For years, Trump has publicly said that Comey and James should be punished for something. But Siebert reportedly balked at the idea of bringing criminal charges that he thought lacked merit. After news of his objections surfaced in the press, he abruptly departed.

The fallout was swift. That weekend, in the wake of Siebert’s departure, Trump went on a social media tirade, demanding that the attorney general, Pam Bondi, move swiftly to prosecute his perceived foes. “They’re all guilty as hell,” Trump wrote of Comey and James in a Sept. 20 Truth Social post—which, according to the Wall Street Journal, may have been intended as a private message. “JUSTICE MUST BE SERVED, NOW!!!”

By the following Monday morning, Trump had installed a new top prosecutor in the Eastern District of Virginia: Halligan, his former personal attorney, who until now had never prosecuted a case. Despite her lack of prosecutorial experience—and reportedly against the urging of veteran prosecutors in her office—Halligan pressed forward. Within days of her arrival, she secured an indictment against Comey for false statements to Congress and obstruction. Two weeks after that, she persuaded a separate grand jury to indict James for mortgage fraud.

This is around when I entered the picture—on Saturday, Oct. 11.

Until she texted me, I’d spent much of that morning catching up on news stories about the case Halligan brought against James, which had just been handed up on Thursday, Oct. 9. The indictment accuses the New York attorney general of misrepresenting how she intended to use a Norfolk, Virginia property when she applied for a loan to purchase it back in 2020.

Specifically, prosecutors say that she told lenders the property would be used as a “second home” when, in reality, she used it as a “rental investment property, renting the property to a family of (3).” By misrepresenting the purpose of the property, the indictment alleges, James was able to obtain a more favorable mortgage rate.

While many commentators ridiculed the case, a few were quick to proclaim that Halligan had an “airtight” case against James.

I was decidedly among the skeptics. Putting aside the apparently retaliatory nature of the charges, it wasn’t clear to me that the facts alleged in the indictment amounted to a crime at all. The mortgage agreement James signed, which used standard Fannie Mae language, required her to treat the property as a “second home,” mandating that she keep it “available” for her personal use. The agreement explicitly allowed James to rent the home after one year of ownership, and it allowed occasional renting within the first year.

Though the indictment notes that James declared “thousand(s)” of dollars in rent on “tax form(s),” it provides scant details about the circumstances of the supposed rental arrangement, including the timing and amount collected. Without knowing those details, I found it difficult to assess whether James had even violated the mortgage contract—much less whether she’d committed a crime by fraudulently entering into it or making false statements on her application intending to deceive anyone.

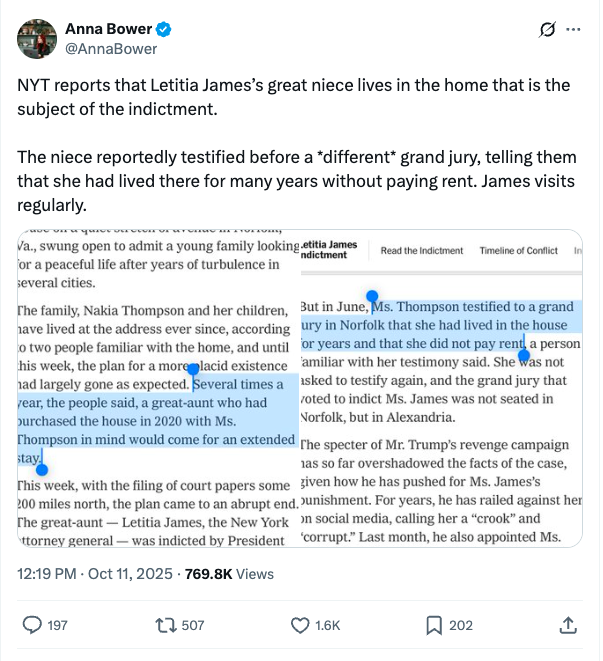

All of which is why, last Saturday, I took particular interest in a New York Times story about the Norfolk home at the center of the James case. The report revealed that the property is occupied by James’s grand-niece, Nakia Thompson. Several times a year, the report said, James stays at the property with Thompson and her children, who have lived there since James purchased the home in 2020.

The Times further reported that Thompson appeared before a Norfolk grand jury in June, testifying that “she had lived in the house for years and that she did not pay rent.” According to the report, Thompson was not asked to testify again, and the grand jury that voted to indict James was seated in Alexandria rather than Norfolk.

As I saw it, the Times report tended to undermine the indictment’s central claim: that James used the home as a “rental investment property.” The evidence, assuming the Times report is accurate, would be exculpatory, I reasoned, in that it tends to show that James did not primarily use the property as a means to collect rent.

I decided to share the article on X, formerly Twitter, as I often do when notable developments arise in relation to the legal cases I cover for Lawfare. Shortly after noon, I tapped out a post, linking to the Times article and summarizing it as follows:

NYT reports that Letitia James’s great niece lives in the home that is the subject of the indictment. The niece reportedly testified before a *different* grand jury, telling them that she had lived there for many years without paying rent. James visits regularly.”

I included two screenshots from the story, one of which highlighted this quotation: “Ms. Thompson testified to a grand jury in Norfolk that she had lived in the house for years and that she did not pay rent.”

Not long after that, at 12:48 p.m., I followed up with a second observation: “This is important exculpatory evidence bc the indictment accuses James of seeking a ‘second home’ mortgage when in reality she intended to use it as an ‘investment’ home by renting it.”

I didn’t think much of the tweets at the time. Sharing other journalists’ reporting is a routine part of how I try to keep people apprised of the cases I follow.

But the prosecutor who personally presented James’s case to the grand jury apparently saw my tweets very differently.

***

When I received the 1:20 p.m. connection request on Signal—an encrypted messaging service that many journalists use to communicate with sources—my first reaction was that the user identified as “Lindsey Halligan” couldn’t actually be Halligan.

“Anna, Lindsey Halligan here,” the first message read. “You are reporting things that are simply not true. Thought you should have a heads up.”

The user on the other end had selected a setting to make all messages in the chat disappear after eight hours, so I took screenshots of the exchange as it happened to make sure a record of the back-and-forth was preserved. Those screenshots are all available here.

Even as I took this precaution, I assumed the exchange was a hoax because, while it is not unusual for lawyers to reach out to me about my reporting or commentary, it is highly unusual for a U.S. attorney to do so regarding an ongoing prosecution—particularly in a high-profile case in which her conduct is already the subject of immense public scrutiny. Halligan has publicly said little about the cases she is pursuing against the president’s enemies. And I didn’t believe she would message me to complain about a tweet that merely summarized other journalistic coverage of grand jury testimony.

With all that in mind, I hypothesized that the message was from someone impersonating Halligan, either to troll me or as a part of some kind of disinformation campaign.

But there was an easy way to validate my correspondent’s claim to be Halligan. I’d met Halligan once before, a few years ago in West Palm Beach, Florida. At the time, the Justice Department was investigating Trump’s unlawful retention of classified materials and the FBI had executed a search at Mar-a-Lago. Halligan was one of the former and future president’s personal lawyers litigating over the search and the handling of seized materials.

Our meeting was happenstance: I ran into her and another Trump lawyer, James Trusty, at a restaurant inside The Breakers hotel, where I dined after covering a hearing before Judge Aileen Cannon for Lawfare. When I introduced myself to the pair, they’d made no secret of their dissatisfaction with how I’d characterized Trusty’s presentation during the hearing—particularly, my use of verbs like “gripe” and “complain” to describe his arguments to the judge.

The Guardian would later report that Trusty had been overheard telling Halligan that he had no interest in talking to reporters from Lawfare on account of our coverage. Still, my conversation with them that evening was otherwise pleasant enough. And I suspected that the real Halligan would remember me.

So I accepted the Signal request and typed out a response, explaining that I needed some additional details to confirm her identity. “Can you tell me where we first met, and who you were with?” I asked.

The person purporting to be “Lindsey Halligan” responded one minute later: “Breakers; Trusty. Got your name from your X account.”

This changed things. I had never spoken publicly about my run-in with Halligan and Trusty at The Breakers. So it seemed exceedingly unlikely that a Halligan impersonator would be able to accurately answer the question, let alone within one minute.

As improbable as it had seemed just minutes ago, it now appeared that I really was texting with interim U.S. Attorney Lindsey Halligan.

Later in the week, I verified that the text exchange had genuinely been with Halligan—or, at least, with Halligan’s phone. I obtained her cell phone number from an independent source and added the number as a contact on my phone. Signal immediately associated the phone number with the “Lindsey Halligan” account with which I had been texting.

But that was later. For now, I was pretty sure my correspondent was Halligan. So I did what any reporter would do: I started asking questions.

“Ok, I’m all ears,” I said after thanking her. “What am I getting wrong?”

“Honestly, so much,” Halligan replied. “I can’t tell you everything but your reporting in particular is just way off.” She then said it was clear to her that I jump to “biased conclusions” based on what I read rather than “truly looking into the evidence.”

I felt confident that Halligan was alluding to one of the tweets I’d posted that afternoon. Other than the tweets, I hadn’t published anything of substance about the James case; my colleague, Molly Roberts, has been running point on that matter for Lawfare. What’s more, Halligan had mentioned that she found my Signal contact on my X profile, suggesting that she had been looking at my tweets.

To confirm, I sent Halligan a link to the post in which I summarized Thompson’s grand jury testimony as reported by the Times. “Are you saying that something I said in this post is inaccurate?” I asked. “And if so, what?”

Halligan replied: “You’re assuming exculpatory evidence without knowing what you’re talking about. It’s just bizarre to me. If you have any questions, before you report, feel free to reach out to me. But jumping to conclusions does your credibility no good.”

Halligan’s real beef seemed to be with the Times, not me, though she wasn’t saying what was wrong with the Times’s story either. I brought this up in my response, pointing out that my post explicitly credited the Times story, not my own reporting. “Did they get something wrong?” I asked.

“Yes they did but you went with it!” she said. “Without even fact checking anything!!!!”

Then she added this: “And they are disclosing grand jury info - which is also not a full representation of what happened. I guess I expect them to do that but I was surprised by you running with it.”

Note that there is nothing improper about the New York Times disclosing grand jury information. The rules of grand jury secrecy, codified in Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, don’t apply to the press. And they don’t bind defense attorneys or witnesses either. So if, say, Thompson or her lawyers had dished to the New York Times about her testimony and the Times had reported about her account, nobody would be violating any rule.

On the other hand, it is generally improper for prosecutors to disclose matters that took place before a grand jury. Rule 6(e) very explicitly covers “an attorney for the government,” and it very specifically prohibits those it covers—subject to certain exceptions—from “disclos[ing] a matter occurring before the grand jury.” And the Justice Manual, which serves as the official statement of Justice Department policies, places detailed restrictions on prosecutors’ use of matters before the grand jury. The matters reported on by the Times are matters of which Halligan would be intimately aware, as she is reported to have personally presented the case to the grand jury.

Avoiding grand jury secrecy violations is one reason Justice Department officials so frequently offer “no comment” on ongoing investigations or cases, preferring instead that the department “speak through its court filings.” And that’s why my dialogue with Halligan struck me as so unusual. Reaching out to a reporter to complain about tweets concerning another publication’s coverage of grand jury testimony seemed uncharacteristically risky for a government lawyer.

I told Halligan that I’d be happy to retract or correct anything I had tweeted that was untrue. “But I can’t do that if I don’t know what the supposed error is,” I said. “Can you be more specific?”

She directed me to the indictment. “It says she received thousand(s) of dollars in rent,” she said, presumably referring to James. Then she added: “I can’t tell you grand jury stuff.”

At this point, I broadly understood Halligan to be conveying a few things to me. The first is that the Times story did indeed disclose grand jury information, but that she believed some part of its account was either inaccurate or misleading or lacked the full context of what occurred. Though she hadn’t explicitly said what grand jury information the Times had disclosed, I interpreted the focus of her ire to be the paper’s account of Thompson’s testimony, which I’d summarized in my tweet.

The second point is that Halligan seemed to be responding in some way to the substance of Thompson’s reported testimony—specifically, that she did not pay rent—by directing me to the indictment, which alleged that James reported “thousand(s)” of dollars in rental income on “tax form(s).”

This did not seem to me to be much of a conflict. I had interpreted the Times to be saying that Thompson was not currently paying rent and had gone for years without doing so, not that she had never paid any rent at any point.

The indictment’s wording on this point is odd and ambiguous. It conspicuously omits the timing and the amount of money in rental income James supposedly reported on her “tax form(s).” And, while the “tax form(s)” are not publicly available, James’s state ethics disclosures are.

Those disclosures report rental income on the Norfolk property only once, back in 2020, for a sum of between $1,000 and $5,000. That James might have collected a relatively small sum of rental income at some point half a decade ago does not contradict the idea that Thompson has lived there for years without paying rent. Nor does it show that James violated her mortgage agreement, given that the contract allowed occasional rentals, even during the first year.

To be sure, it’s possible that the evidence at trial will show otherwise. But the indictment Halligan had filed, coupled with the publicly available facts, don’t promise that it will. And the specific allegation she’d pointed me to did not on its face contradict the testimony I’d summarized in my tweet.

Beyond that, though, I still couldn’t understand precisely what Halligan was trying to tell me. Was she suggesting that Thompson had lied to the grand jury? Or that the Times had mischaracterized Thompson’s testimony? Or something else entirely?

I explained my thinking to Halligan in my next response, writing as follows:

I read the NY Times report as saying that Nakia testified that she lived in the house for years without paying rent. Though the indictment says there were thousands of dollars of rent paid *at one point,* I don’t see that as inconsistent with her testimony as reported by the NY Times. James’s ethics disclosures report between $1,000-$5,000 in rent back in 2020. But after that, she didn’t disclose additional rental income. I’m still not sure I understand what’s incorrect about the NY Times account or my summary of it.

Halligan replied:

Anna,

You’re biased. Your reporting isn’t accurate. I’m the one handling the case and I’m telling you that. If you want to twist and torture the facts to fit your narrative, there’s nothing I can do. Waste to even give you a heads up.

In turn, I reminded Halligan that it was she who had approached me to tell me that I’d compounded or repeated something inaccurate in the Times’s account of Thompson’s testimony. “I am happy to correct it, but I can’t do so without a sense of what I supposedly got wrong,” I said.

“Continue to do what you have been and you’ll be completely discredited when the evidence comes out,” she replied.

I still wasn’t sure what I’d supposedly gotten wrong, or why she’d contacted me, or what to make of it all.

And for what it’s worth, the Times doesn’t know either. In a statement to Lawfare, the paper said that the Justice Department had raised no issue with the Times about its story: “We’re confident in the accuracy of our reporting. The DOJ declined to comment before publication and has not raised any concerns with us since the story was published more than a week ago.”

It was clear that Halligan and I had reached a point of diminishing returns.

“I’d love to talk further when you are at liberty to be specific,” I said.

And we left it there—at least for a few hours.

***

Later that evening, I followed up with Halligan. She’d seemed frustrated by the end of our conversation that afternoon. But she’d also told me that I could “feel free” to reach out to her if I had any questions. And I wanted to find out if she was serious about that.

“I’m curious for your thoughts more broadly,” I wrote at 9:19 p.m. on Saturday. “What are you most frustrated that reporters aren’t focusing on or writing about with respect to this case?”

“No frustration generally,” she replied. “You’re the only reporter I reached out to.”

The next day, I tried again. I asked if I should expect additional charges against James, as the Wall Street Journal had reported over the weekend.

“You don’t report fairly!” Halligan replied. Then she added: “I can’t discuss any potential charges with reporters. If evidence arises that warrants further charges, I’ll look into it!”

I was genuinely confused. Only the previous day, she had essentially invited me to fact-check other outlets’ reporting before tweeting about them. Now she was refusing to engage when I did exactly that. “I thought you said I was welcome to reach out to you about what other outlets are reporting,” I said.

She wrote back: “Why do you report on what other outlets are reporting? If I was you, I’d develop sources myself and out compete them all!”

I expressed my confusion in my next message: “What was the purpose of reaching out to me, if not to open a line of communication? Was it just to insult my reporting?”

“No, it was for you to correct it, which you refused to do,” she replied.

We’d come full circle, back to my tweet summarizing the Times article. Something about it had seemed to strike a nerve with Halligan, but I couldn’t figure out exactly what or why.

“I am more than happy to correct it, but you still haven’t told me what’s incorrect!” I said. “What precisely is wrong with the tweet?”

Halligan didn’t respond.

Over the next several days, I followed up twice more, asking Halligan for her perspective on a variety of questions I had about the James case. My texts went unanswered.

***

Halligan had said quite a lot during our correspondence, although much of it was hard for me to parse. But there was an important thing she had not said during the entirety of our communications: “Off the record” or “On background” or anything whatsoever about the terms on which we were talking.

As anyone who professionally engages with the media as routinely as Halligan would know, the default assumption when a reporter speaks with a public official is that everything is “on the record,” meaning that anything the source says can be printed with attribution. If the source wishes to speak confidentially, she can negotiate how the information will be used. “On background” means that the information the source provides to a journalist can be published, so long as the journalist doesn’t reveal the source’s name or identifying information. “Off the record” means the reporter can’t print what the source tells them at all. There are other variations too. But with any condition, a fundamental premise is that the reporter must agree to speak on that basis.

In the course of my work as a journalist, I frequently agree to speak with sources on background or off the record. I take my duty of confidentiality seriously and I have never burned a source by revealing confidential communications.

I certainly would have been willing to speak with Halligan on background or off the record. But she never raised the terms on which we were speaking at any point during the two days in which we exchanged texts.

After Saturday evening’s message, she went radio silent. By the end of the week, this much was clear: U.S. Attorney Lindsey Halligan was ghosting me.

***

Even now, I remain mystified by Halligan’s texts to me. She is currently the most scrutinized prosecutor in the country, widely seen as hand-picked to prosecute her boss’s political enemies. Even the slightest misstep could be seized on and picked apart by defense counsel representing James, who analysts expect will seek dismissal of her charges based on selective or vindictive prosecution.

It’s not as if Halligan didn’t understand the rules of engagement with the press. For years, she worked as a member of Trump’s criminal defense team, which routinely courted media attention, despite accusing prosecutors of improper leaks. And now, as a prosecutor herself, she has accused former FBI director Comey of lying about whether he authorized a colleague at the bureau to serve as an anonymous source in news reports about an ongoing investigation. A central issue in that case, which Halligan reportedly also presented to the grand jury herself, concerns the nature of interactions between reporters and federal law enforcement sources.

So the irony was hard to ignore when, just days after she texted me, Halligan reportedly fired two senior career prosecutors for supposedly “leaking ‘unauthorized’ information to the press.” That same week, she released a statement in response to an MSNBC story about a separate case against a Democratic state lawmaker. “EDVA enforces a strict zero-tolerance policy on the unauthorized disclosure of information concerning ongoing investigations or cases,” she said. In the same story, Justice Department spokesman Chad Gilmartin is quoted saying: “While we do not confirm the existence of, nor comment on, specific investigations outside of our public filings, any Department employee who leaks deliberative or investigative developments only jeopardizes the integrity of investigations and the incredible work of federal law enforcement.”

For someone so attuned to the risks of speaking out of turn—and so willing to punish others for allegedly doing so—Halligan’s decision to reach out to me over text remains baffling.

She knew I was a journalist. She approached me. She invited my questions. She even encouraged me to stop chasing other reporters’ stories and focus on my own.

Turns out, she gave me a great one.

Epilogue

Earlier today, I reached out to the Justice Department’s Office of Public Affairs, seeking comment for this story. In addition to a transcript of my Signal exchange with Halligan, I also outlined some of my questions related to the story: Were these authorized communications? Is it consistent with DOJ policy or other applicable guidance for senior Justice Department officials to discuss ongoing prosecutions on Signal disappearing messages? Does the Department take the position that the contents of the messages are consistent with its legal obligations and DOJ policy? Does Halligan deny that these were in fact her texts? Does the Justice Department dispute any of the facts reported in the New York Times article discussed in my exchange with Halligan?

I told the Justice Department that my deadline was 4:15 p.m.

In response, the department sent the statement quoted at the outset of this piece. In addition, just a few minutes before the deadline, my dormant Signal connection with Halligan suddenly came alive again.

At 4:10 p.m., she texted me: “By the way—everything I ever sent you is off record. You’re not a journalist so it’s weird saying that but just letting you know.”

I responded: “I’m sorry, but that’s not how this works. You don’t get to say that in retrospect.”

Halligan was unpersuaded: “Yes I do. Off record.”

“I am really sorry. I would have been happy to speak with you on an off the record basis had you asked,” I said. “But you didn’t ask, and I still haven’t agreed to speak on that basis. Do you have any further comment for the story?

To my surprise, she kept going: “It’s obvious the whole convo is off record. There’s disappearing messages and it’s on signal. What is your story? You never told me about a story.”

I didn’t respond. It was time to publish my story. I’ll text it to her.

Postscript: Read the full exchange between Lindsey Halligan and Lawfare’s Anna Bower here.

Hours after Lawfare published this article, Justice Department spokeswoman Natalie Baldassarre provided the following additional comment: “Thank you for including my statement in your story. I just realized I spelled Lindsey’s name wrong in the initial response, would you mind correcting?”