Christopher Wray’s First Problem: What to Do About Andrew McCabe

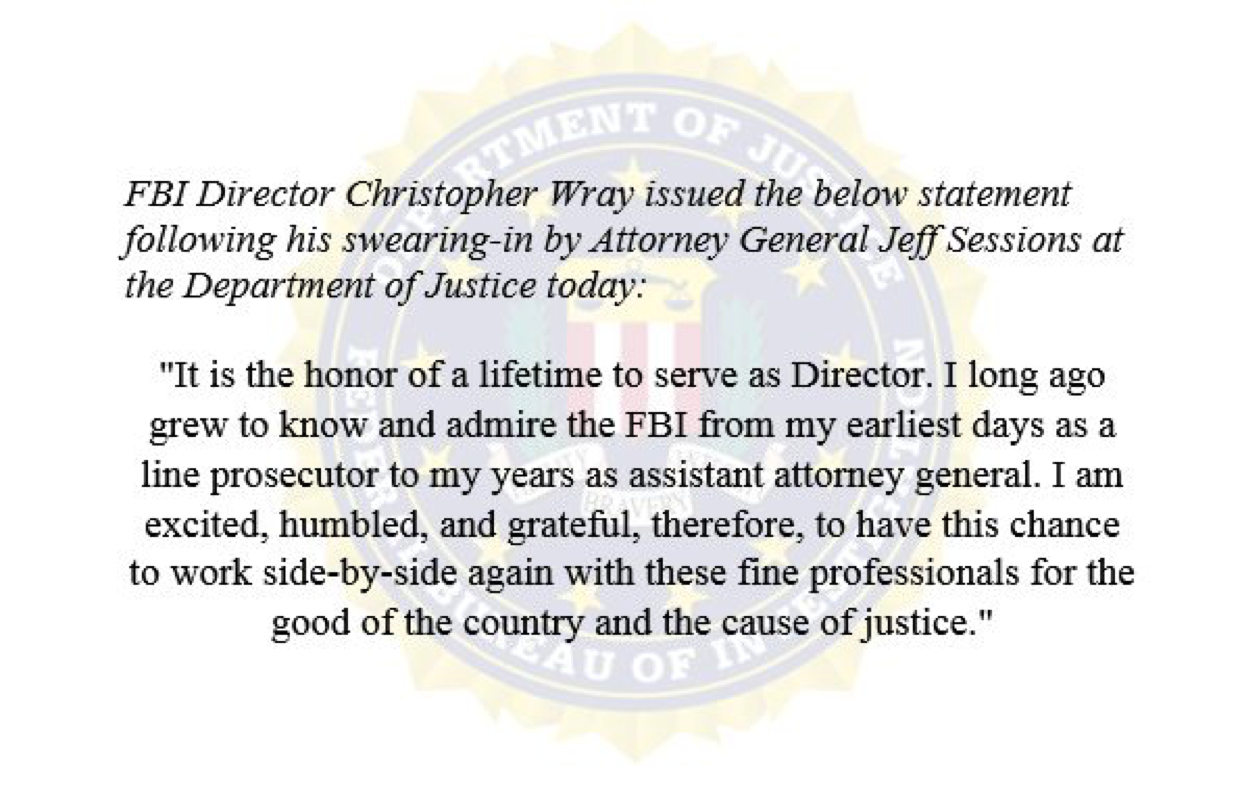

Christopher Wray took the oath of office at the FBI yesterday and thus started the clock ticking on a difficult problem he’s going to have to address: the fate of his deputy, Andrew McCabe, who has been serving as acting director since President Trump fired former FBI Director James Comey.

Christopher Wray took the oath of office at the FBI yesterday and thus started the clock ticking on a difficult problem he’s going to have to address: the fate of his deputy, Andrew McCabe, who has been serving as acting director since President Trump fired former FBI Director James Comey.

Trump’s got a bee in his bonnet about McCabe. He’s had it for a while. During one of the conversations with Comey that the then-director memorialized at the time and revealed in his prepared testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee, Trump raised the question of “the McCabe thing”—apparently referencing donations provided to McCabe’s wife by Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe during her run for state Senate. He raised the issue again in his interview with the New York Times, saying, “We have a director of the F.B.I., acting, who received $700,000, whose wife received $700,000 from, essentially, Hillary Clinton.”

More recently, the president has taken to attacking McCabe openly on Twitter—indeed, calling for his ouster and calling him a swamp beast:

Problem is that the acting head of the FBI & the person in charge of the Hillary investigation, Andrew McCabe, got $700,000 from H for wife!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 25, 2017

Why didn't A.G. Sessions replace Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe, a Comey friend who was in charge of Clinton investigation but got....

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 26, 2017

...big dollars ($700,000) for his wife's political run from Hillary Clinton and her representatives. Drain the Swamp!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 26, 2017

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley has also gotten in on the action. Grassley opened Wray’s confirmation hearing with an attack on McCabe, positioning him as the source of the “cloud of doubt” that Grassley believes to be “hang[ing] over the FBI’s objectivity.” The senator has also written to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein criticizing McCabe’s involvement not only in the Clinton email investigation but also in the Flynn investigation, arguing that McCabe is biased against Flynn because of the latter’s support for an FBI agent who made a complaint against McCabe. The same day that Grassley’s letter to Rosenstein was released, Trump’s private attorney, Jay Sekulow, criticized McCabe for alleged conflicts of interest in a series of tweets.

Now that the president has a new FBI director, how long will it be until he expects Wray to get rid of this corrupt fifth columnist whose firing he has publicly called for?

By contrast, within the bureau, McCabe’s star has risen a great deal since he became acting director in May—and for good reason. His testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee—during which he asserted that Director Comey “enjoyed broad support within the FBI and still does to this day”—was extremely well received within the bureau and solidified his popularity. He has led the institution under extraordinarily difficult circumstances ably and without a fumble. He has been dignified in the face of attacks. At a time when law enforcement leadership has not shrouded itself in glory, McCabe has represented the bureau extremely well.

We spent some time yesterday gauging how the organization would react to his removal as deputy director, should Trump demand that of Wray. The short answer is that while there would likely be tolerance for Wray’s choosing his own leadership team over time, he would do himself grave damage within the organization by shunting McCabe aside in any fashion understood to be responsive to the political demands of a boss who already fired one director. In other words, complying with Trump’s demands would make Wray look like a hatchet man.

Wray comes into office with both goodwill and a lot of suspicion he will need to overcome. The suspicion flows inevitably from the dubious circumstances of his appointment and the workforce’s general enthusiasm for his predecessor. The goodwill, in turn, stems from Wray having a serious background in law enforcement, his being a far better choice than nearly all of the alternatives Trump was kicking around, and his having acquitted himself admirably in his confirmation hearing and sent appropriately reassuring messages. People seem ready to give him a chance.

But the McCabe matter will be a real test. Before his service as acting director, McCabe had a mixed reputation. He was well-liked among many employees, some of whom described him as intelligent and levelheaded—a manager who took the job seriously without raising his voice. On the other hand, some felt that he had risen too quickly at FBI headquarters; he’s a lawyer, not a tough guy; some folks thought he should have recused himself from the Clinton email matters because of his wife’s political activity; and while we haven’t heard any significant complaints about his job performance in any of his management roles, he’s always had a bit of a reputation as somewhat outside the core of the bureau’s culture.

Until Comey was fired, that is. McCabe today is a figure of wide admiration for standing up for the bureau when it was under political attack. If there was ever a question about whether he was culturally FBI, nobody’s asking it any more.

We don’t have the impression that the removal of McCabe has been the subject of a great deal of water-cooler conversation at the bureau. But it is safe to say that his removal would be badly received and that employees would rally around him just as they did around Comey. (Let’s not forget the “Comey is my Homey” T-shirts at FBI Family Day.) It’s also safe to say that removing McCabe, at least if Wray does it quickly or in a fashion that appears responsive to political pressure, would also undo a great deal of the goodwill with which he walked in the door yesterday among people he has to lead for the next 10 years.

There’s another complication for Wray: Removing McCabe would face certain legal complications. McCabe is a career FBI special agent, not a political appointee, and he's a member of the Senior Executive Service. Civil service rules prevent a simple firing, and while McCabe can be reassigned or encouraged to retire, he cannot be reassigned for four months after installation of a new agency head without his consent. More broadly, to reassign a 21-year veteran of the FBI for political reasons would send a strong message that the FBI is no longer an apolitical organization, an identity of which FBI employees are fiercely proud, even if it doesn't run afoul of civil service protections—at least if it were done without McCabe’s cooperation.

The problem for Wray is that Trump might not care about any of these niceties: not about whether he’s making his FBI director look like a political toady, not about how the workforce understands the director and certainly not about compliance with civil service protections.

So what happens the next time Trump tweets about the deputy director, suggesting he be replaced? Does Wray replace McCabe? Does he rope-a-dope and not comply but also not say anything? Does he quietly over time install his own team and ease McCabe out in a graceful fashion? Or does he speak up in response to political pressure and become the next law enforcement leader at whose hands Trump feels unprotected and betrayed?

.png?sfvrsn=48e6afb0_5)