Facebook Suspended Trump. The Oversight Board Shouldn't Let Him Back.

The Facebook Oversight Board should be mindful that Facebook is not a government—and that the platform’s decisions denying active accounts or taking down posts pose no threat of loss of liberty to any person.

Facebook created its Oversight Board to review the platform’s content moderation decisions and provide legitimacy to the moderation process, but it remains to be seen whether the result will be wiser decisions or escalating mistakes. The board now faces a momentous choice: whether to reverse Facebook’s indefinite suspension of Donald Trump.

The board is meant to be independent of the company. Its members are paid six-figure salaries through an independent trust, endowed by Facebook with $130 million. At least for now, the board’s review is limited to individual decisions to take down content and does not yet extend to decisions to keep up content unless such decisions are referred to the board by Facebook. The relationships among Facebook, the Oversight Board, and the trust are in their early stages of development, but the board’s first set of decisions demonstrates a decidedly libertarian tilt. The board overturned Facebook’s decisions, for example, to take down a post containing misinformation about COVID-19 treatments, a post containing veiled threats of violence to a political leader, and a post with an offensive reference to a religious group—in a country, Myanmar, that had previously experienced violence to which Facebook contributed in 2018. Under the board’s rulings, these posts are to be restored.

The board is now considering Facebook’s suspension of Donald Trump’s account. As it does so, we hope it will be mindful that Facebook is not a government—and that the platform’s decisions denying active accounts or taking down posts pose no threat of loss of liberty to any person. Facebook, moreover, has free expression interests of its own in preventing the use of its platform to cause human rights violations and threats to democracy.

These perspectives are worth emphasizing because the board seems thus far insufficiently attentive to relevant differences between Facebook’s position, as a private media platform, and that of a government. The board’s initial decisions—five out of six of which reversed takedown judgments by the company—seem more tied to legal standards for government actions than to rules for private speech and editorial judgments. Do these decisions accord sufficient weight to Facebook’s legitimate interests in not contributing to the development of hateful attitudes toward vulnerable minorities or of threats to democratic government? We worry that the board’s principal charge—“to protect free expression,” according to its charter from Facebook—may produce more adherence to an abstract notion of “everyone has a right to speak” without adequate attention to the severity of the harms caused by speech that, implicitly or explicitly, works to incite violence against minorities or against the institutions of democracy.

The decision to suspend Trump’s account was a thorny one, and we understand why Mark Zuckerberg is happy to refer the question to others. If the board chooses to return Trump’s access to his account, its decision here may be viewed as a precedent by other heads of state—including those who might seek to use Facebook to advance authoritarian agendas by igniting violence and hatred. Decisions about such global leaders reasonably can differ from treatment of others, and Facebook may choose to have different criteria for heads of state and similar global leaders; indeed, it has apparently done so in the past. Although what leaders of government have to say may be of unusual public interest, their words can have much greater influence by virtue of their positions of power. Social media platforms work as a megaphone for those already famous, potentially amplifying the instantaneous reach and effect of their speech to the entire world. Allowing access to Facebook by a man so recently impeached for incitement of violent assault on the workings of democracy thus poses unprecedented risks.

So far, the board seems more concerned with the risks of excluding speech from the public discussion than the risks of including it. As noted, in most of its initial decisions, the board found that Facebook violated its own rules in taking down material. One post referred to French President Emmanuel Macron as “the devil” and appeared accompanied by a text about drawing a sword against infidels who criticize the Prophet. Facebook initially treated this as a veiled threat, warranting removal; the board disagreed and restored the post. Another post suggested that “something’s wrong with Muslims psychologically”—or, in the board’s subsequent translation, “male Muslims have something wrong in their mindset”—which Facebook initially treated as a form of hate speech. The post in question also included a photo of a “Syrian toddler of Kurdish ethnicity” who drowned trying to reach Europe and suggested that the child might have grown up to be an extremist. Again, the board concluded that Facebook should not have blocked the material.

Although its charter mentions human rights only in connection with freedom of expression, the board’s bylaws contemplate that members will receive training in “international human rights standards.” In its decisions, the board has referenced not only international free speech standards but also international human rights norms concerning nondiscrimination and the right to life and security.

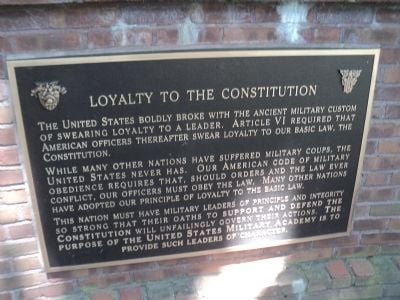

In seeking guidance from such international standards, and in developing and interpreting Facebook’s own Community Standards, Facebook and the board should attend to two key differences between a privately owned social media platform and a government. First, they should address not just the claims of removed users but also Facebook’s interest in its own freedom of expression. Facebook has legitimate interests in being free to express itself through policies about content posted on its platform, as well as in protecting its reputation and pursuing economic returns—and for this reason, it has latitude to guard against use of its resources to injure or undermine human rights and the democratic process. Facebook’s leaders embrace those values. Its policies’ references to human rights are noted above, and Facebook has asserted its “respect for the democratic process” as a basis for exempting “political speech” from its ordinary fact-checking rules.

These values—of human rights and democracy—can guide the platform’s own decisions and the board’s interpretation of its rules. Human rights and democratic processes are mutually reinforcing; together they undergird developing transnational norms condemning unconstitutional disruptions of democratic governance. Thus, political leaders who seek unconstitutionally to disrupt democratic governance might well warrant distinctive treatment. Moreover, as interpretive guidance on the application of human rights standards suggests, the ways in which private entities should aspire to protect democracy and human rights should vary depending on “the severity of the enterprise’s adverse human rights impact.” Neglect of these dimensions would make the board shortsighted and inattentive to Facebook’s own values.

The board should also squarely consider a second key feature of Facebook’s identity as a private company, not a government. Unlike coercive government power, constrained by legal standards in the United States and internationally, Facebook as a private entity lacks the ability to put speakers in prison or subject them to fines, and the board should give greater due to this essential fact. Facebook enables others to communicate but does not wield the powers to punish, to make war and peace, or to tax. Being denied access to Facebook is not incarceration. It is not a deprivation of the liberties a democratic government promises to protect. Nor does it prevent speakers from using other, albeit sometimes slower moving or more expensive, forms of communication to convey the same message. Indeed, the former president has already begun sending out messages from the “Office of the Former President.”

Because Facebook cannot impose the severe penalties governments can impose, the company retains more room to reach judgments and to set and apply rules that advance its own values. Despite understandable worries about the power of big tech platforms to suppress some points of view, there is no reason to believe that Facebook—either in taking down the posts about Macron and Muslims, or in suspending the former president’s account—was trying to censor ideas that are a legitimate part of public debate. Plenty of other speakers on Facebook explore the reliability of the U.S. election returns, and whether one candidate is preferable to another, and make calls to assemble and speak out. In contrast, invitations to commit violence, and religious-, ethnic- or gender-based invective, are not an “essential part” of the explication of ideas in a digital forum. Ideas expressed in two of the removed posts considered by the board—that it is inconsistent to criticize French satirists but not the Chinese government for anti-Muslim conduct, or criticism of the French president—can be expressed without resort to invective or implying or encouraging violence.

But invective and comments threatening or inviting violence, especially if echoed by others, can provoke real harm, as recent events around the world make all too clear. Efforts to limit those harms—as Facebook did in taking down those two posts, and in suspending Trump’s account—fall comfortably within the ambit of this private company’s legitimate sphere of decision.

The board’s members may not have rich knowledge of all the local and national contexts for such posts—although it is possible that the board is better equipped than Facebook’s internal team to gather expert information on different contexts. Specific contextual knowledge is of special importance in evaluating coded speech, which may be used to communicate messages designed to exclude understanding by outsiders. People nimbly devise codes to convey messages conveying the equivalent of overtly racist or violent calls, but without the use of express terms; code words also can communicate plans to commit violence. Is the board equipped to look realistically at and recognize such codes?

The board members have great expertise in standards of freedom of expression, applied to governments, under international and constitutional standards—but it is less clear that the board includes experts on how speech has led to human rights violations. Global legal standards addressing speech—unlike those developed under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution—deploy proportionality review and consider the relative harm that the challenged action seeks to prevent, as compared to the relative burden on rights. The board in its first set of opinions invoked international norms, including of “necessity” and “proportionality,” for evaluating government conduct claimed to infringe on rights. But is the board sufficiently alert in applying these norms to the most serious harms, as is necessary for appropriate evaluation of when a measure limiting expression is a justified response?

Digital media have been described as “inextricably linked” to genocide and mass atrocities in the 21st century. Some kinds of speech may lead to what the German Constitutional Court calls “aggressive emotionalisation or the lowering of inhibitions,” resulting in a population accepting or encouraging concrete acts of discrimination and violence, which in turn can lead to even greater atrocities and threats to democracy. Scholars show how such “dangerous speech” may take place over a relatively long period of time, producing cumulative and devastating impacts. The board is tasked with advancing freedom of expression; impairment of free speech is one kind of human rights violation, but so too is degradation of individuals and groups. Will members of the board consider how attacks on minorities and on democratic institutions—if not prevented or remedied—undermine not only individuals’ equality and dignity but also the very institutions and cultures that support freedom of speech?

In considering Facebook’s suspension of the former U.S. president’s account, the board should, as it applies norms of proportionality, consider the values of free speech and the degree of harm to speech rights in light of the fact that the suspension decision is not a state-enforced punishment. The board should also consider, as weighing in favor of the suspension, Facebook’s own interests as speaker, editor and facilitator of communication in not having its facilities used to cause serious human rights violations and threats to democratic government. It should draw on expertise not only from free speech experts but also from experts in the use of words to incite human rights violations. While many users would find it of interest to know what the former president thinks about many things, his views will still be accessible through news media and other avenues even while suspended from Facebook’s free and amplifying platform.

A contextual approach is critical. We hope the board considers Trump’s past words and their effects, the nature of his influence as a speaker, the likely targets or audience of the speech, the social and political context, and the nature of the medium. (In a previous case, the Oversight Board gave attention to the particular character of the speaking group as bearing on its intent.) The board must consider as well whether a too-rapid reversal of Trump’s suspension would depreciate the seriousness of specific disturbing past conduct and encourage further such conduct in the future by Trump and by others like him. It remains an important question to what extent the board generally should consider speech expressed outside of Facebook in evaluating potentially harmful activity on the platform. But at least in the case of the former president, Facebook decision-makers would be wise to consider the broader facts, including Trump’s Jan. 6 speech, his Facebook posts and the larger context in which they occurred.

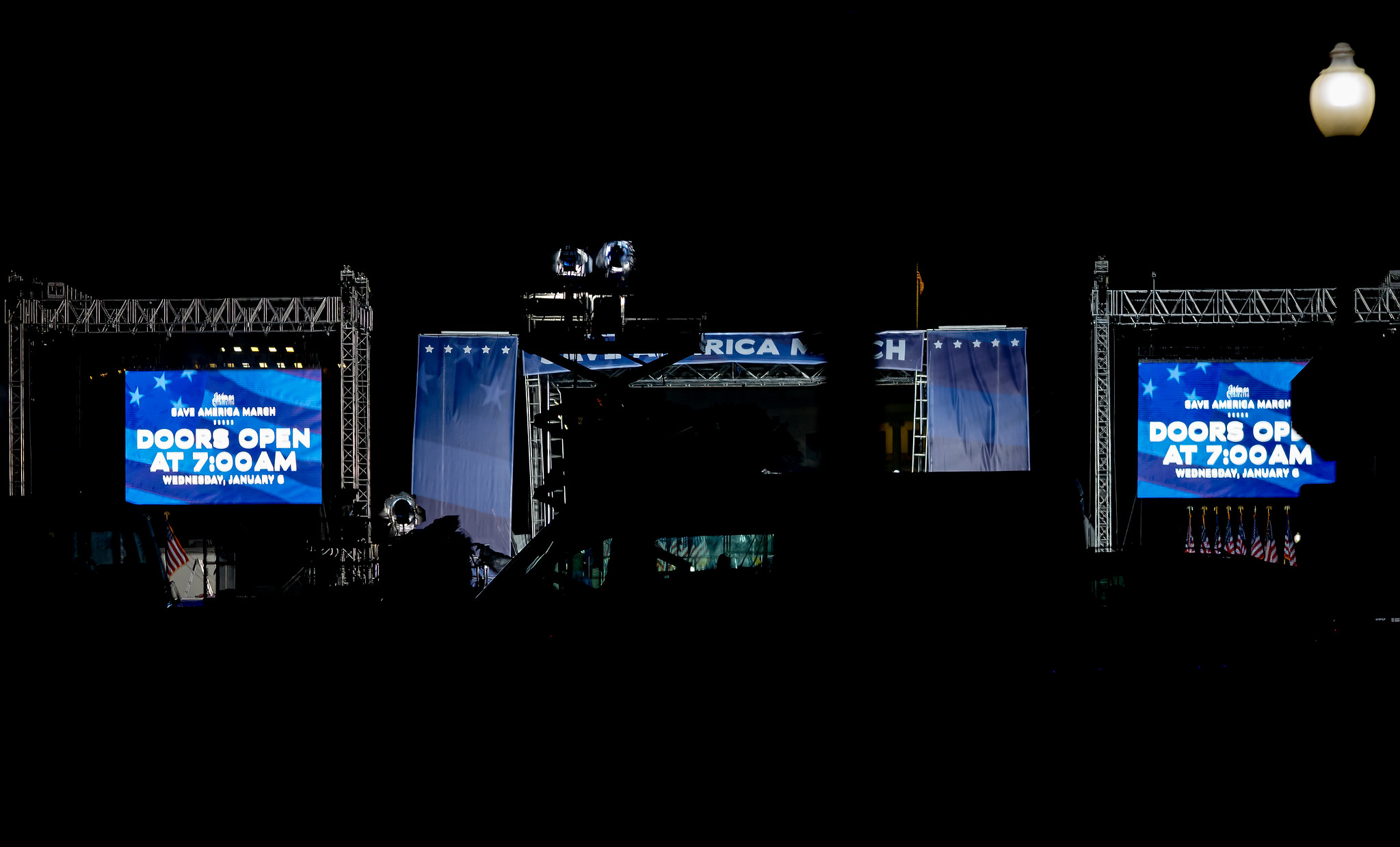

Weighing the values of free speech and the risks of harm alongside the role of a private company with its own rights and duties, we believe that granting Trump renewed access to Facebook in the near future would be a mistake. Trump is a master of code speaking, such as his speech on Jan. 6 to the crowd of his supporters saying, “[Y]ou’ll never take back our country with weakness,” and his prior tweet, “Big protest in DC on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!” The meaning of these phrases cannot be determined from the words alone; one must consider the general tenor, the tone of voice, the groundwork laid by prior communications and the setting of each expression. Certainly, some receivers of Trump’s messages fully believed he was summoning them to use arms and violence to stop the institutions of U.S. democracy from effecting a peaceful transition of power.

Trump’s words to his supporters on Jan. 6 attacked the democratic order of the United States. By insisting, contrary to fact, that he had won the election, and encouraging his supporters to believe that their rights to vote had been nullified by the opposition, Trump engaged in classic “mirroring” behavior associated with incitements to rights violations. Trump’s speech, given in person (not on Facebook) to the crowd, delivered an incendiary message that was echoed by Trump’s Facebook postings that day, which made repeated false and inflammatory statements about the election, described as “stolen,” “fraudulent,” a “landslide” that was “taken away from all of us—from me, from you, from our country,” statements at odds with other parts of the message to “go home in peace.” In another Facebook post, he wrote, “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly unfairly treated for so long. Go home with love in peace.” In other words, he accused those acting to implement the results of the election in favor of Biden of obstructing the will of the voters, when it was he and his supporters who were doing so. The virulent claims of election fraud appear stronger than the “go home” message. Trump’s “off-platform” behavior provides an important context for evaluating his Facebook posts and deciding whether to continue the suspension of his account.

Whether or not Trump intended to rile up the crowd to attack the Capitol or instead behaved with reckless indifference to the likely impact of his speech, his words were without doubt effective: A mob overcame security forces and surged into the Capitol, resulting in five deaths and, according to recent reports, over 100 injuries before order was restored. Evidence showed that despite urgent pleas from lawmakers for the president to take action to protect them, Trump waited more than two hours after the Capitol was overrun before issuing a statement calling for “peace” and at the same time repeating inflammatory and false claims that the election had been stolen. The delay appears to have reflected his desire to see the disruption continue; the House Judiciary Committee Majority Staff Report on impeachment notes descriptions of Trump as “borderline enthusiastic” or “delighted” that the certification of the electoral vote was being delayed. A majority of both the U.S. House of Representatives and of the U.S. Senate—though not the two-thirds required to convict—found Trump to have engaged in an impeachable offense of inciting the insurrectionary mob.

A decision to restore Trump’s access to the megaphone of Facebook so soon after this event will be read by too many as an implicit endorsement and vindication. His efforts to overthrow the constitutional order of the United States merit more than a digital slap on the wrist.

This conclusion is reinforced by the five-year history of Trump using sometimes coded, sometimes more explicit, speech to encourage violence. As a Vox article noted, “As far back as 2015, Trump has been connected to documented acts of violence, with perpetrators claiming that he was even their inspiration.” Trump’s 2017 comments encouraging police to treat suspects roughly leave little doubt of his willingness to encourage violence, a willingness that Facebook will be facilitating if it returns him to its pages in the near future. Likewise, his long history of invoking animosity toward groups based on their ethnicity or religion—including his 2015 campaign comments about “Mexicans,” associating them with “drugs,” “crime” and “rapists,” and his campaign promise for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”—suggests a likely future willingness to engage in such speech.

With respect to incitements to violence and racism, the usual call in the United States is to counter bad speech with good speech. But this approach, for all its many virtues, is much less effective in the digital era, in which platforms curate content to enhance users’ engagement and sculpt exposures to echo rather than challenge what the user has already seen. And the risks to the important values promoted by freedom of expression are lower when a private entity like Facebook exercises editorial judgment than when governments seek to put speakers in prison.

Facebook is devoting substantial resources to bringing together experts to evaluate, from a free speech perspective, the platform’s implementation of its own standards. Facebook and the Oversight Board should capitalize on the possibilities for learning and experimentation in approaches to difficult or dangerous speech. To do so, both entities should take more account of Facebook’s own distinctive situation as a private digital platform. And they should draw on a broader range of expertise—for example, from the growing field of genocide studies—than that currently reflected in the board, to give due weight to preventing violations of rights to life, to freedom from invidious discrimination, and to democracy.

The world of law could benefit by seeing a plurality of approaches to issues of regulating harmful speech—a delicate and complex challenge, especially when regulation involves addressing coded speech that, if openly expressed, would clearly violate rules against provoking hatred or violence. Facebook’s innovation in creating the Oversight Board, the emerging interactions between Facebook and the board (and the trust), and discussions by experts and the broader public could provide a new model to advance understandings and practices around the balance of freedom and safety. The balance is a difficult one to strike—but as a private media platform, Facebook and the board can and should, at times, strike the balance differently than would a government.

.png?sfvrsn=48e6afb0_5)