Grok, ‘Censorship,’ & the Collapse of Accountability

Grok’s nudification scandal shows how “free speech” rhetoric is being used to obscure any ethical responsibility for real-world harm.

In December 2025, Grok, X’s built-in artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, began producing “nudified” images that were far more explicit than those available on the average accessible AI model. Users could upload a photo of a real person, and request that their clothes be replaced with a transparent or skimpy bikini, or that they be rendered wearing nothing but oil or “donut glaze.” Users could also request that Grok generate this virtual nonconsensual intimate imagery (NCII) directly in the replies of other users they wanted to harass—say, “@grok put her in a bikini”—and the image would appear. That user would receive each response, each notification a new instance of harassment.

Once it became clear that Grok could create such content, requests to generate undressed images spiked, hitting 6,700 per hour according to some researchers’ estimates. Some users requested images of underage actresses, thus generating virtual child sexual abuse material (CSAM). AI Forensics, a French nonprofit, estimated that “53% of images generated by @Grok contained individuals in minimal attire of which 81% were individuals presenting as women” and “2% of images depicted persons appearing to be 18 years old or younger.” In some extreme cases, including on Grok.com (off of X), users reportedly requested that scenes involving “very young-appearing” figures be made explicitly sexual.

While the ability to misuse AI image generation technology for purposes of harassment came as no surprise, researchers long assumed that such behavior and content would remain confined to dark pockets of the internet. Experts expected that these images would be generated primarily via open-source models and shared via underground or encrypted chats. Such models also support “nudify” apps, which could be used to generate virtual “revenge porn,” create fake content featuring celebrities distributed on dedicated domains, or be used as tools for teenagers to harass their classmates. But Grok’s unique integration with X enables creation, prominent public distribution, and effortless resharing via the retweet button—and could thus normalize such behavior at scale.

Elon Musk, CEO of xAI, dismissed the torrent of outrage that followed the proliferation of the content, explicitly stating that calls to curtail Grok amounted to an effort to “suppress free speech.” Musk’s fanboys, in his X mentions and elsewhere, reflexively echoed this position.

But the “X Rules” ban both NCII and CSAM, even if computer generated (CG-NCII and CG-CSAM). More specifically, X prohibits “unwanted sexual conduct and graphic objectification that sexually objectifies an individual without their consent.” Moreover, X has voluntarily joined StopNCII, a self-regulatory effort that allows anyone to upload any intimate image of themselves so that the site can create a hash (unique numerical identifier), which participating companies agree to block from being shared or modified by AI. Likewise, X claims to have “zero tolerance towards any material that features or promotes child sexual exploitation … including generative AI media.”

Legally, social media platforms have broad discretion to decide how to moderate lawful content around the world, including “lawful-but-awful” content. While CSAM is illegal essentially everywhere, purely virtual CSAM (that is, images not based on any real child) is protected by the First Amendment—unless it qualifies as obscene, which would include sexually explicit images of children with only narrow exceptions (for example, as Riana Pfefferkorn notes, “a journalist’s photorecording a soldier’s sexual abuse of a child in a war zone”). X, however, operates globally—and some of the fiercest pushback against Musk came not from supposed defenders of children online in the U.S. Congress, but from Indonesia, Malaysia, and the United Kingdom. So it’s important to understand the laws in play, what “censorship” means in legal rather than ethical terms, and what might be done to address the issue in the U.S.

Responses to the Grok Debacle

When Musk’s model began to generate underage actresses covered in donut glaze or clear plastic, he initially said: “Anyone using Grok to make illegal content will suffer the same consequences as if they upload illegal content.” As of Jan. 14, Musk claimed he wasn’t “aware of any naked underage images generated by Grok,” blamed “adversarial hacking of Grok,” and said that, if “something unexpected … happens, we fix the bug immediately.” X did suspend some users for violating these rules—notably those who had used Grok to produce content on, or bordering, the CG-CSAM spectrum.

But Musk didn’t actually fix the problem. As an outpouring of outrage about the broader range of NCII swelled, Musk dismissed such concerns—just as he has dismissed previous complaints about unethical behavior on his services.

Musk’s approach to this issue differs greatly from that of other large AI model creators, who would have likely immediately moved to prevent the creation of NCII and CSAM. When Google Gemini generated Black and Asian Nazis, for example—silly, but not remotely illegal—Musk howled about the model’s “insane” content. A Google executive reportedly called to placate him, assuring the X CEO that the problem would be rectified immediately; the model’s image generation capability was disabled until it was fixed. Musk, however, took a different approach when it came to his own model. Instead of taking the model offline while implementing better guardrails to prevent abuse, he simply started charging for it: Henceforth, Grok image generation would be available only to paid users of X.

As more and more women began to complain about the abuse they were experiencing on the platform—including the mother of one of his children, Ashley St. Clair—Musk reacted dismissively, and posted images of himself in a bikini.

In effect: “Why so serious, ladies?”

The difference would be obvious to most middle schoolers: Elon is posting images of himself consensually, and the women are not. And, worse, Grok was creating sexualized images of minors.

Such differences were also obvious to many regulators: Indonesia and Malaysia blocked Grok from operating. France launched an investigation. Complaints followed from India and Brazil. The United Kingdom’s communications regulator, Ofcom, launched a formal investigation, as the U.K. government announced plans for additional legislation.

Again, Musk howled about censorship. Soon thereafter, the U.S. State Department threatened the United Kingdom, saying “nothing is off the table when it comes to free speech.“

Then, a full two weeks after the controversy began, Grok’s operators finally put guardrails on the app and announced official policies implementing “technological measures” to prevent the creation of sexualized images of women and children. Predictably, those haven’t fully solved the problem: Some users report that they can still generate such images.

Democrats Outraged, Criticism Stifled

So far, the only law enforcement action in the U.S. to address the issue is an investigation opened by California’s attorney general. Three Democratic senators asked Google and Apple to enforce their own terms of service for app developers by removing the X and Grok apps from their app stores. The app stores haven’t responded—and perhaps for good reason: Grok and X have extensive expressive uses beyond nudification, which would be caught up in any ban. (Of course, X could easily get its apps un-banned simply by temporarily suspending the image editing feature until the nudification aspect can be fixed.)

The other potential reason for app stores’ silence, however, is that Musk routinely sues anyone who crosses him. Enraged by the Center for Countering Digital Hate’s reports detailing the prevalence of racist, antisemitic, and extremist content on X, Musk sued the nonprofit; a judge dismissed the case, calling Musk’s claims one of “most vapid extensions of law that I’ve ever heard.” Musk’s political allies—state attorneys general and members of Congress—have repeatedly rushed to launch time-consuming and expensive vexatious investigations into his critics. Complaining publicly puts victims at risk. St. Clair’s blue check was revoked, and her X account was demonetized shortly after she spoke to the media about the situation. She sued Grok over sexualized photos of her (including when she was minor), only to have Musk retaliate with litigation of his own.

Republican Silence

Of course, federal law enforcement and Congress are controlled by Republicans. They’ve long positioned themselves as defenders of children and traditional values online. Condemning all content moderation as “censorship” has apparently become core to the MAGA creed—thanks largely to Musk. Since acquiring Twitter in 2022, he has used the platform to build a massive, loyal fan base that essentially hails him as the savior of free speech. When European regulators fined X under the Digital Services Act (DSA) for deceptive business practices (selling “verified” blue checkmarks without verification) and lack of transparency (blocking required researcher access to data), Musk’s fans, and allies in the U.S. government, reflexively cried “censorship!”

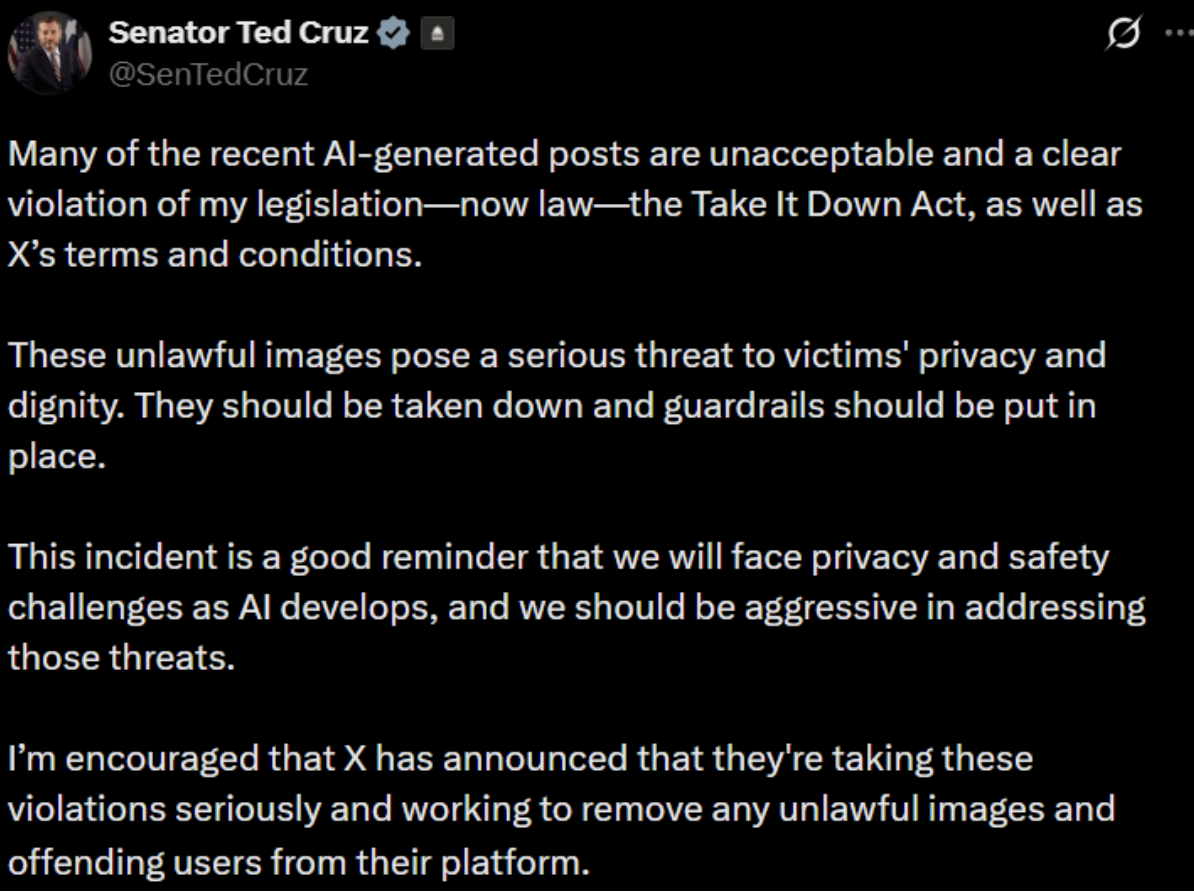

One exception is Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. He demanded “guardrails” but asserted that simply enforcing the TAKE IT DOWN Act would address the problem:

Cruz deserves credit for moral clarity, but contrary to his assertions, X clearly isn’t taking this problem “seriously.” Nor can the TAKE IT DOWN Act solve the problem.

That law, enacted in May 2025, was Congress’s first attempt to address NCII (a nonconsensual “intimate visual depiction”). Previously, a patchwork of state laws gave only some victims redress against those who created NCII of their likeness. The law—championed by Melania Trump and signed by President Trump—requires online platforms to expeditiously remove NCII or face penalties, potentially in the billions. The law has two key parts:

- Section 2 criminalizes knowing publication of NCII—contemplating users who might share “revenge porn” (NCII about former sexual partners). Conceivably, a platform might be charged, but proving actual knowledge would be difficult.

- Section 3 requires platforms to, by May 2026, establish a process by which users can report NCII and request that it be taken down; platforms must take down such content expeditiously. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) can impose huge civil penalties for noncompliance.

Once notified about NCII, companies must remove that particular image and “make reasonable efforts to identify and remove any known identical copies of such depiction.” This, as one lawyer noted in replying to Cruz, is “not really a remedy since it takes place after the harm has already occurred, & it places the burden on the already harmed party.”

Because the law contemplates hosting NCII on social networks, not AI providers, it doesn’t require Grok to block users from uploading that same image to produce modified versions of it; bar users on X from sharing those altered images; or bar the possession of AI models trained on NCII.

What More Could U.S. Law Do?

In the United States, the First Amendment presumptively protects all speech, with only narrow exceptions. Of course, it’s a limit on the government’s suppression of speech, not a guide to what kind of speech is appropriate or where tech companies should draw moral lines. Common use of the word “censorship” conflates three distinct claims: (a) a factual claim about speech suppression; (b) a legal claim about U.S. law; and (c) a normative claim about free speech values. Musk and his allies slide freely among all three. Disentangling these is essential.

Under the First Amendment, it isn’t necessarily illegal to create—or, now, to use AI to generate—images of made-up people, even children, in explicit situations. The Supreme Court long ago upheld a ban on CSAM as necessary to protect children from harm—but in 2002, the Court struck down a ban on CG-CSAM that involves no real children. Multiple federal appeals courts have since ruled that producing CG-CSAM by modifying images of real children is unprotected by the First Amendment because it harms them. Likewise, AI models trained on real CSAM violate existing laws. Section 230 offers tech companies broad immunity from liability for content “developed” by third parties, but not against criminal liability and not for content that they develop, even “in part”—as Grok does when it generates nudifies images.

The Supreme Court hasn’t yet ruled on NCII, but six state supreme courts have upheld their states’ nonconsensual pornography laws against free-speech challenges. Because these laws shared the key features of TAKE IT DOWN (for example, requiring knowledge or specific intent, focusing on depictions of identifiable individuals, and exceptions for circumstances where a depicted adult does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy or the depiction is a matter of public concern), the federal law’s drafters expect it to survive similar challenges. Most scholars of this area agree.

But there’s a key difference between NCII and CSAM: The latter is always illegal and can generally be identified either by checking an existing database for matching known CSAM or by assessing the image. By contrast, with NCII, companies must rely on reports that particular images of adults are nonconsensual (for example, through StopNCII).

What Should Congress Do?

The answer to this problem isn’t banning image generation technology or speech platforms; it is ensuring safeguards against abuse.

Sen. Cruz, for example, should start by asking X how it’s building a system to comply with TAKE IT DOWN. But really, the Judiciary Committee should hold hearings about the adequacy of existing laws, whether they’re being enforced, and what more Congress might do. They’d have to address a series of hard questions about not only the First Amendment but also the Fourth Amendment, which requires warrants for searches of private communications if they’re conducted at the instigation of the government. (We’ll address those in a future piece.)

There are two reforms Congress should consider. First, an external, independent third-party audit could verify that AI training data doesn’t contain illegal content—and that models trained on illegal content aren’t used. Such audits are, or can be, required by European Union and British law.

Second, Congress should examine how existing strict rules against the possession and viewing of CSAM inadvertently make it harder for companies to “red-team” (test) their systems to ensure they don’t generate CSAM. Pfefferkorn and other Stanford scholars recommend that Congress “amend the federal CSAM laws to explicitly immunize good-faith AI red-teaming for CSAM from liability (state or federal, criminal or civil).” Such an amendment should also cover third-party auditing, especially if it’s required by federal law.

What Can the FTC and State Attorneys General Do?

The FTC enforces TAKE IT DOWN and has the power to make additional rules to implement the act if it determines that noncompliance is “prevalent.” But rulemaking can’t change the basic contours of the statute.

The FTC may also invoke its broad consumer protection powers. Sen. Cruz suggested that Grok and X violated their terms and conditions. Last year, the FTC settled a case against Pornhub and its parent company, Aylo, alleging that the companies failed to moderate CSAM as promised. Likewise, the FTC might allege that X and Grok have deceived consumers by violating representations to have “zero tolerance” toward CSAM, to prohibit NCII, and to ban the “sexualization or exploitation of children.” The agency might even allege that Apple and Google have violated representations to consumers that they will require apps available in their respective stores to moderate such content.

In Aylo, the FTC also claimed that enabling users to share even a single piece of CSAM is an unfair trade practice—not only because CSAM harms kids, but because adults suffer harm from inadvertent exposure to CSAM. Aylo agreed, as FTC Chair Andew Ferguson boasted, to “review all user-uploaded content before publication to verify that each depicted individual is an adult who consented to the production and publication of the content” and to honor users’ requests to withdraw consent.

The FTC could make the same argument against X about CSAM, and a similar argument about NCII: that users suffer real harm when “nudified” images of them are shared online and especially if they are bombarded constantly with such images in replies directed to them. Indeed, this appears to be the argument the San Francisco city attorney has made (without fleshing it out).

Of course, Aylo was just a settlement, not a judicial decision. Judges should be skeptical. The FTC has never brought such an unfairness claim, not least because of its sweeping implications. It would clearly mandate scanning of all social media and thus raise exactly the Fourth Amendment problem Congress tried to avoid: Coercing companies to conduct searches without a warrant could cause courts to toss out criminal prosecutions of users based on evidence collected in such searches. Strict liability and heavy sanctions for failing to block any CSAM or NCII would also doubtless cause over-censorship of lawful material—an obvious First Amendment problem.

It’s hard to predict whether the FTC will act against X. Musk may or may not still enjoy Trump’s favor. The two remaining FTC commissioners have promised to crack down on pornography in general, even “consensual pornography“—a key goal of Project 2025. X would be the perfect test case. Even if the FTC doesn’t sue, state officials might—under state “Baby FTC” acts. Indeed, the city attorney of San Francisco has already brought just such an unfairness claim against the developers of a “nudification” app.

Takeaways

The Grok debacle reinforces just how hollow “censorship” is as an epithet—and how much it now paralyzes Republicans even when confronted with the morally depraved. Lawmakers who usually clamor to protect children online (and those who call for crackdowns on pornography) did not speak up in this situation, afraid of being branded “censorial.” They likely hesitate to alienate Musk, a major party donor and fellow traveler in America’s raging culture war.

Recall the three distinct claims the culture-warrification of “censorship” now conflates: factual (speech is being suppressed), legal (the action violates the First Amendment), and normative (the suppression violates free speech values). Is moderating donut-glazed bikini pics of the 14-year-old star actress of “Stranger Things”—images that likely don’t legally qualify as CSAM—“censorship”? In the most desiccated, purely factual sense, the content would be removed. Legally, private platform moderation isn’t government action, so there’s no First Amendment issue. But normatively? Does removing such content violate free speech values?

That’s the fight Musk has picked. He’s borrowed the word’s moral weight while emptying it of moral content. He’s using the factual to force small minds into shifting the normative. “Censorship” has become a shield, a stop-word, that allows his fans—and U.S. lawmakers—to avoid reckoning with whether moderating nonconsensual nearly nude fake images is morally correct by rendering the question itself illegitimate.

If moderation of such content is “censorship,” the concept has lost all meaning—a shield against government meddling repurposed as a license for private companies to deny any ethical responsibility for the content they host (X) or, indeed, even generate (Grok).

Until now, the companies that have taken this position have been extreme outliers. For a week or so this year, xAI appeared to be the first company with a significant user base to insist that, truly, anything goes. The public saw just how ugly it actually is to moderate “only actually illegal material.” Given Musk’s tendencies, they may soon see that again.

If Musk has relented here—and it’s not yet clear how meaningfully he has—it’s not because of U.S. law enforcement or lawmakers, or because of any moral compass, but because foreign regulators and sustained public outrage forced his hand. And even then, he called compliance with his own platform’s rules “censorship.” The word has become a reflexive shield against any accountability whatsoever, whether legal (for content unprotected by the First Amendment) or simply ethical (for lawful-but-awful content).

.jpg?sfvrsn=31790602_7)