How Iranian-Backed Militias Do Political Signaling

Iran and its proxies are using attacks for political signaling. They may be creating escalation challenges that bring them closer to war with the U.S.

Iranian-backed groups have used the Israel-Hamas war as justification for a number of strikes against Israeli and U.S. forces. Hezbollah fired on Israeli soldiers and struck targets in northern Israel. The Houthis launched missiles toward Israel and at American ships and downed an American MQ-9 Reaper drone flying over the Red Sea.

But perhaps most immediately worrying for the U.S. are Iranian-backed militias’ drone and rocket attacks on U.S. installations in Iraq and Syria. As of this writing, according to the Department of Defense, there have been at least 97 attacks on U.S forces in Iraq and Syria since the uptick in attacks began following the explosion at al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza on Oct. 17. While the Pentagon indicated there was a pause in attacks during the temporary cease-fire in Gaza, the tempo has increased again since the cease-fire ended on Nov. 30.

Behind these strikes are two sets of actors with two distinct sets of goals. Iran is using its proxies’ attacks to signal to the U.S. and Israel that it is capable of expanding the conflict. By urging its proxies to attack, Iran also seeks to maintain and bolster its legitimacy among the proxies as the principal anti-Israel and anti-U.S. power in the region. Iranian-backed militias are answering the call to prove to Iran they are a worthwhile proxy and to signal to their local constituencies that they represent their interests and have the requisite military capacity to do so effectively. These proxies are also shrewd political actors, attempting to use the attacks to advance their independent political objectives—such as expelling U.S. troops from the region.

It’s worth noting this is not the first time Iranian-backed attacks on U.S. installations in Iraq and Syria have been used for political signaling. For instance, in April 2021, there were a series of attacks on logistic convoys and Balad Air Base in the lead-up to a meeting of the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Dialogue. In December 2018, an attack came a day after then-President Trump’s visit to the U.S. al-Asad Air Base. Similar attacks in the past five years or so have been purposefully limited in lethality and aimed primarily at political signaling, so as to not provoke a major U.S. response. By comparison, some attacks from a decade earlier during the U.S.-Iraq war, such as the 2007 Karbala attack, appear to have had the primary aim of causing U.S. casualties.

The recent attacks by Iranian-backed militias on U.S. forces—though they have remained limited in lethality and thus seemingly political in nature—have been more persistent than previous political messaging strikes. In the past, U.S. airstrikes had deterred further attacks. That has not been the case this time around.

Who Is Signaling, and to Whom?

The root cause of the recent increase in attacks is the war in Gaza. Numerous statements from Iranian-backed militias have explicitly linked their recent attacks to the Gaza conflict. Proxies’ statements and actions in support of Gaza are in line with statements and actions taken by Iran, which remains an ardent supporter of Hamas. But a general “solidarity with the Palestinians” message leaves much obscured, in terms of Iran’s political goals and those of its proxies.

Two goals seem to undergird Iran’s relation to the strikes: signaling its regional power to Washington to expand the conflict if it so chooses and signaling its control over Iran-backed militias.

Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian declared at the UN that the U.S. would “not be spared from this fire” if Israeli military actions in Gaza continued. Brig. Gen. Esmail Qaani, head of the Quds Force, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’s (IRGC’s) extraterritorial operations arm, echoed similar remarks on Nov. 16. Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who has ultimate foreign policy decision-making power, stated recently in an official visit with Iraq’s prime minister in Tehran that Iran and Iraq need to collaborate to impose political pressure on the U.S. and Israel.

Intelligence appears to show Iran is encouraging proxies to attack U.S. installations in Iraq and Syria and that Iran is urging other groups within its orbit, like the Houthis, to launch attacks on Israeli and American troops. There is also some evidence of Quds Force media coordination across proxies’ social media channels. Iraqi proxies and Quds Force members have reportedly had several meetings about the conflict in Gaza, the potential for leveraging Hezbollah for escalation in southern Lebanon, and the Islamic Resistance in Iraq. Further strategic and operational coordination seems to occur within the Quds Force and Hezbollah-led “joint operations room” among Iraqi, Palestinian, and Yemeni groups in the Axis of Resistance. This entity was established after the U.S.’s killing of former Quds Force commander Lt. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, to centralize decision-making and facilitate operations within the Axis of Resistance, and the conflict in Gaza demonstrated its durability.

However, while Iran is encouraging the attacks, and even highlighting some of them in its official media, it is still trying to maintain some distance from proxies seemingly for deniability and to prevent a large-scale conflict with the United States (more on this below).

It is hard to know definitively from open sources to what extent militias are acting of their own volition or at Iran’s behest. But Tehran’s control over its proxies is limited; absolute control is rare for a sponsor. Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, Harakat al-Nujaba, and Kata’ib Hezbollah—prominent members of the Iraqi security structure, the Hashd al-Shaabi, or Popular Mobilization Forces—and other Iraqi proxy groups have their own political parties and interests independent of Iranian direction and jockey among each other for relevance to local populations and to Iran.

The militias are likely using these attacks to signal to local populations, other militias, and Iran that they are credible players in the region with the power to inflict damage on Israel and U.S. forces. It would be difficult to maintain a meaningful position in the Axis of Resistance without conducting some attacks.

Claiming attacks in support of Palestinians frames proxies as the “righteous protectors” of those in Gaza and as legitimate adversaries of Israel and the United States—the aggressors as perceived by Iran and local populations. Iran-affiliated groups operating under the banner of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq said their attacks targeting U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria were in solidarity with the Palestinians: “We affirm the continuation of our operations in support of our people in Gaza and in response to the brutal massacres committed by the occupation against defenseless civilians.” Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq leader Qais al-Khazali announced Iraqi militias were attacking U.S. installations as retribution for U.S. support for Israel. On Oct. 18, following the explosion at al-Shifa Hospital, a military spokesman for Kata’ib Hezbollah said that the U.S. is an “essential partner in killing [Gazans]” that must “bear the consequences.” Kata’ib Hezbollah statements have repeatedly blamed the U.S for Israeli actions in Gaza, praised the “steadfastness” of Palestinians, and stated that the U.S. actions in support of Israel demand punishment.

But Iranian-backed militias in Iraq have also connected their attacks to the removal of U.S. forces from Iraq. Pushing U.S. troops out of Iraq has been a goal of militias in Iraq for years. Hadi al-Amiri, head of the Badr Organization, pushed for the removal of U.S. troops in November 2017, and the Iraqi parliament even voted to remove U.S. forces in the aftermath of the Soleimani strike in January 2020.

The militias seem to be using the current crisis to accelerate the push for removal. In a post on the Telegram channel for al-I’lam al-Harbi (affiliated with the Islamic Resistance in Iraq), the Islamic Resistance in Iraq pledged to continue its “operations against the occupation forces until the last soldier is removed from our country.” Al-Amiri said on Oct. 30, “The time has come to remove the international coalition forces from Iraq.” He called upon the Iraqi government to take all necessary measures to set a short timetable for their exit. On Nov. 1, Akram al-Kaabi, the secretary-general of the Harakat al-Nujaba Movement, said, “The Iraqi Islamic Resistance decided to liberate Iraq militarily, and the matter was settled. Blessed are the mujahideen. There will be no stopping, no truce, no retreat.” Kata’ib Hezbollah spokesperson Abu Ali al-Askari has repeatedly claimed the group’s attacks are meant to expel U.S. forces from Iraq.

Balancing Signaling Strikes With Avoiding War

While both Iran and its proxies are taking an aggressive stance seemingly to signal their influence and legitimacy, neither appears to have incentives to use the current moment to set off a full-scale conflict with the United States.

As mentioned above, Iran and Iranian-backed militias have repeatedly used attacks on U.S. installations in the region for political signaling. In 2021 and 2022, Iranian-backed militias conducted attacks seemingly to pressure the U.S. during negotiations regarding a potential Iran nuclear deal and to warn the U.S. against increasing economic pressure on Iran if the negotiations failed. Iran-backed militias in 2020 launched a spate of attacks in response to the death of Soleimani. In January 2022, on the second anniversary of Soleimani’s killing, U.S. counter-drone systems shot down two drones with “Soleimani’s revenge” written on the wings.

However, since 2017, rarely have attacks consisted of more than 10 rockets or more than three drones. Out of over 200 attacks conducted by Iran-backed militias since 2017, fewer than 20 have wounded any U.S. troops or contractors. The limited lethality of the attacks suggests that Iran and its proxies seek to avoid a wider conflict and reaffirms that the attacks are focused on their stated political goals.

If Iranian-backed militias wanted to conduct more lethal attacks and provoke a major U.S. response, they could.

The past two months of strikes fall in line with this preexisting pattern. Iranian-backed militias have relied almost exclusively on rocket and drone attacks consisting of mostly a few rockets or a couple of drones. With the large stocks of rockets and drones these militias possess, they could engage in attacks of much greater scale that would be far more threatening to U.S. troops. Furthermore, militias have mostly chosen not to use their most lethal capabilities—cruise and ballistic missiles.

Iranian-backed militias continue to maintain significant stocks of Iranian-made rockets and drones. They could use large numbers of these drones to overwhelm U.S. installations’ air defenses and then strike the installations. Russia has demonstrated that numerous cheap Iranian drones used in unison can overwhelm air defense systems and strike critical targets. Large-scale rocket attacks could have similarly disruptive effects. Iran also recently unveiled a new jet-powered drone, worrying those who monitor the provision of advanced weapons technology to proxies—a common IRGC practice.

Iranian-backed militias seem to possess Iranian cruise and ballistic missile capabilities. Close-range ballistic missiles were used against the al-Asad Air Base on Nov. 21. Earlier in November, the Islamic Resistance in Iraq unveiled al-Aqsa 1, a medium-range missile purportedly used against U.S. installations in Iraq and Syria. Concern about these capabilities is further exacerbated by the IRGC’s recent unveiling of the Fateh-2 cruise missile.

The January 2020 attack on al-Asad Air Base demonstrated the threat Iran-backed militias could pose to U.S. forces if they utilized these capabilities. In that attack, the Iranians fired 16 theater ballistic missiles, 11 of which landed at al-Asad. More than 100 soldiers and aircrew suffered traumatic brain injuries. U.S. Gen. Frank McKenzie, then serving as commander of U.S. Central Command, estimated that an even greater number of Americans would have been killed or wounded if he had not ordered an evacuation of half the base’s troops the day before.

While perhaps acting aggressively, Iran and its proxies seem to be attempting to avoid a direct conflict with the U.S. They are not using the full extent of their capabilities, and Iran and its proxies have sought to create plausible deniability and dilute blame by creating an umbrella entity—the Islamic Resistance in Iraq—which has claimed the majority of attacks thus far. This brand is a facade for Iranian-backed attacks and groups, reducing the responsibility attributed to any one group and obscuring the links to Iran. This desire to obfuscate attribution while also publicly commending attacks on U.S. installations may seem contradictory. But it is a line that Iran seeks to walk to impose costs on the U.S. in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere in the region without inflicting a level of harm that will produce a large-scale U.S. response.

In official media, Iran does not claim to be behind the attacks. Instead, the attacks are couched in a broad narrative of “resistance” against the U.S. or Israel. In the past, Iranian linkages to proxies in its official media have been more explicit and described in terms of Iran’s support for the Axis of Resistance.

Iran knows it could not withstand a conventional conflict with the United States. Domestic tensions in Iran—reeling from economic issues and the Mahsa Jina Amini protests, along with the subsequent crackdown and executions—also limit Supreme Leader Khamenei’s willingness to create more unrest. Another possibility is that Iran may be taking advantage of the turmoil of the conflict in Israel to bolster its legitimacy with its domestic population, as it did when it entered the Syrian civil war a decade ago. State-organized protests throughout Iran on Oct. 13 to condemn Israel support this view. However, even these efforts were met with backlash at sporting events and online.

Escalation Challenges

Though Iran and its proxy groups are likely not seeking war with the U.S., the unprecedented persistence of the recent attacks creates serious escalation challenges for the U.S.

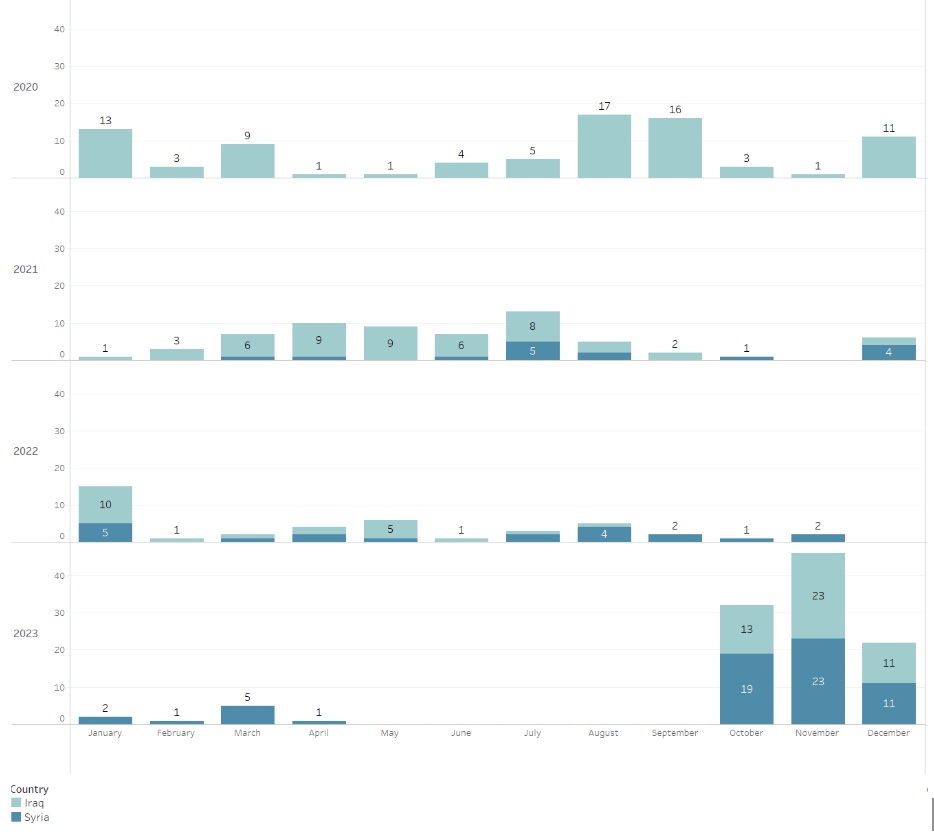

These attacks are markedly different from past signaling strikes in their persistence, tempo, and tactics. They come after an unusually long lull (see Figure 1). Before Oct. 17, Iranian-backed militias had not attacked U.S. troops in the region since early April, and U.S. troops had come under fire only a handful of times in 2023—a dramatic decrease from past years. Even in particularly active years, the attacks were spread across multiple months. As noted above, the number of attacks since Oct. 17 has now risen to at least 97 (the precise number differs based on the source of the reporting, explaining the discrepancy between this number and our figure). The previous monthly high for attacks dating back to 2020 was in August 2020, with 17 (according to Combating Terrorism Center data from January 2020 to December 15, 2023 compiled from publicly available sources—including news and social media in English, Farsi, and Arabic, and other data sets such as Janes Terrorism and Insurgency Monitor and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project). This compilation is also the source for the data in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Iranian-backed attacks on U.S. installations and logistics convoys in Iraq and Syria since the January 2020 Soleimani strike.

This spate of attacks also reflects a change in tactics from the past two years, reminiscent of the previous heightened escalations in 2020, after the Soleimani strike. Since Oct. 17, there have been many days with multiple attacks—sometimes with both drones and missiles—on the same target. The at least 66 wounded U.S. service members resulting from the recent attacks surpasses the number of casualties in 2020, when it was estimated based on open sources that at least 27 were wounded and two were killed.

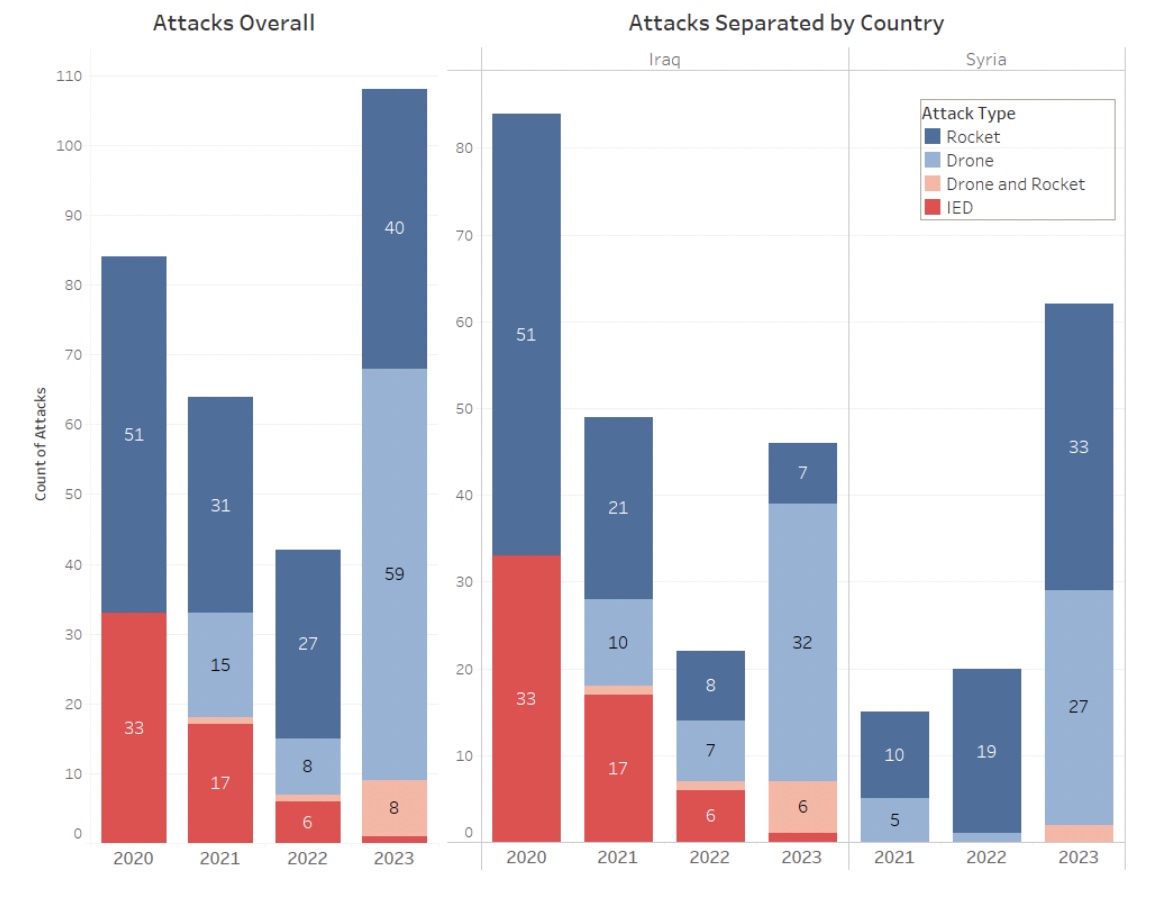

Drones have been used in most of the recent attacks, which is particularly notable in light of the upward trend in Iranian drone proliferation to allies and proxies. Drone systems are becoming easier to mass produce, and their capabilities are getting more precise—allowing Iran to deliver a cheaper, more accurate weapon to proxies to use against their shared adversaries. While drones were first used in attacks against U.S. installations in 2021 (see Figure 2), they have become more common in Iranian-backed militia attacks this year. There have been more than twice as many attacks using drones (at least 67) this year as there were in 2021 and 2022 combined (at least 25 attacks). From 2020 to 2022, there were at least 56 improvised explosive device (IED) attacks, almost exclusively used against logistics convoys. This year, rockets and drones have generally replaced IEDs. There has been only one IED attack this year. Attack precision could be the explanation for this shift: Proxies’ rocket and drone systems have improved over the years and offer more precise targeting than IEDs.

Figure 2. Iranian-backed attacks on U.S. installations and logistics convoys in Iraq and Syria since the January 2020 Soleimani strike, separated by attack type.

(It is worth noting that U.S. forces have been counting as “attacks” only strikes that land near personnel and/or American infrastructure. According to a Defense Department spokesperson, “[a]n attack that happens 4 or 5, 6 kilometers away, we’re not counting as an attack on our forces.” This definitional detail may explain the discrepancy in numbers between the attack counts of the Pentagon and those compiled from proxies’ social media, such as Sabireen News, and other think tank sources. As noted earlier, militia groups may also claim more attacks than actually exist.)

The attacks also appear to be targeted more accurately. U.S. air defenses have thwarted a significant portion of the attacks launched against them. In the past, U.S. installations have been more selective about their usage of air defense systems. Incoming rockets and drones were often poorly aimed and posed little threat, especially in light of the security provided by American base defense systems. Many of the installations field some combination of Centurion Counter-Rocket, Artillery, Mortar (C-RAM) systems; Avenger air defense systems aimed at shooting down low-flying missiles and aircraft, including drones; and Patriot missile batteries capable of defending against cruise and ballistic missiles.

And perhaps most importantly, attacks on U.S. targets in Iraq and Syria have continued in spite of multiple retaliatory airstrikes. The U.S. made clear with the airstrikes it conducted on Oct. 26, Nov. 22, and Dec. 3 that, as following past attacks on U.S. bases in June 2021 and February 2023, the U.S. will forcefully respond to attacks on U.S. troops. The willingness to respond to the attacks that seriously injure U.S. troops has been a critical aspect of deterring these groups from bolder attacks. In the past, attacks quickly subsided following airstrikes. However, this time, Iranian-backed groups have shown more resolve, continuing to strike U.S. troops in the region despite recent airstrikes. Public comments highlighting the U.S.’s willingness to respond to attacks on its forces are effective in communicating and reaffirming the limits and redlines previously established. But if the U.S. seeks to reestablish deterrence, it will have to either climb the escalatory ladder in terms of its attacks or find less overt ways to deter Iranian proxies.

Conclusion

Since the Oct. 17 attack on al-Ahli Hospital, Iran and its proxies have conducted at least 97 attacks on U.S. installations in Iraq and Syria, according to the Department of Defense. The attacks serve as political signaling both for Iran to the U.S. and for proxies to Iran and their local constituents. However, recent attacks differ markedly in tempo and tactics from similar signaling strikes conducted since January 2020. U.S. airstrikes, a previously effective deterrent to Iranian-backed attacks on U.S. installations, seem to carry less weight now.

The path toward reestablishing deterrence is a difficult one, riddled with possible false steps and misperceptions. If Iran and Iranian-backed militias continue attacks for the reasons outlined in this piece, their margin of error is similarly slim. Crawling toward war could turn to lurching into conflict in several ways, including the following scenarios: if more U.S. troops are killed, if Iran appears more explicitly involved in organizing attacks, or if the U.S. kills several IRGC troops, among other possibilities.

The views, conclusions, and recommendations in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect those of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

.jpg?sfvrsn=a7a3d4b3_3)