The Imaginary Unitary Executive

Contrary to the “Decision of 1789” myth, history shows that the first Congress rejected the exclusive unitary model of the presidency—and thus the presidential removal power should be subject to more congressional control than recent Supreme Court decisions have held.

On June 29, Chief Justice John Roberts relied heavily on something called the “Decision of 1789” to expand presidential removal powers. The Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that the structure of the CFPB was unconstitutional as an independent agency, because Congress required the president to have good cause to remove its single director.

Roberts held that such a requirement interfered with a president’s power to supervise the executive branch, because a sole director with for-cause protection would have held too much concentrated power independent from presidential control. Roberts limited this decision to principal officers as singular heads of agencies, as opposed to commissions. However, his expansion of the “unitary executive” theory could continue expanding presidential power and thwart potential reforms to address recent abuses.

President Trump, for example, has fired a number of inspectors general. Could a new Congress protect the independence of inspectors general with for-cause requirements? Or could Congress establish a new independent counsel statute, responding to Trump’s efforts to fire Special Counsel Robert Mueller? May Congress enact reforms to make the Department of Justice more independent from self-protecting presidents and partisan attorneys general? Most fundamentally, what will be the role for Congress and the courts to check and balance the president as the Roberts court expands its separation-of-powers formalism?

The Constitution is famously silent on removal power. Because records of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and the debates over constitutional ratification in 1787-88 are, at best, inconclusive about presidential power, the theorists of exclusive presidential power—many of whom are originalists—have turned to 1789. They see in the first Congress a founding moment of presidential power.

Roberts writes on the second page of his decision, “The President’s power to remove—and thus supervise—those who wield executive power on his behalf follows from the text of Article II, was settled by the First Congress, and was confirmed in the landmark decision Myers v. United States (1926).” But Roberts actually cites few sources from 1789, relying instead on how judges “confirm” this received wisdom about events in that year. This is odd for an ostensibly historical argument. One of the few original sources Roberts cited is a letter from James Madison, who orchestrated a sequence of votes that became known as the Decision of 1789. Roberts uses Madison’s words to summarize: “The view that ‘prevailed, as most consonant to the text of the Constitution’ and ‘to the requisite responsibility and harmony in the Executive Department,’ was that the executive power included a power to oversee executive officers through removal.” But Madison had an interest in telling his own version of his strategy.

Justice Clarence Thomas in concurrence also relied on the First Congress—or to be more precise, he relied on Chief Justice William Howard Taft’s interpretation of it in Myers. Justice Elena Kagan briefly raised questions about the clarity of this interpretation, but Roberts applied something like res judicata to historical interpretation: “The dissent, for its part, largely reprises points that the Court has already considered and rejected,” such as “downplay[ing] the decision of 1789.”

But a justice’s interpretation of a historical event should not itself have any precedential value—certainly not for originalists, who generally say original sources should trump precedent. Instead of reviewing the original debates, however, Roberts rests on what judges have said about 1789 over the past century: Taft in Myers and Roberts himself in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Accounting Oversight Board: “‘Since 1789,’ we recapped, ‘the Constitution has been understood to empower the President to keep these officers accountable—by removing them from office, if necessary.” Roberts wrote in Seila Law: “But text, first principles, the First Congress’s decision in 1789, Myers, and Free Enterprise Fund all establish that the President’s removal power is the rule, not the exception.” The text is far from clear; what Roberts means by “first principles” is even less clear. And Myers and Free Enterprise rely heavily on “the First Congress’s decision in 1789.”

So this really all comes down to what actually happened in 1789 when Congress put together the rudiments of what became the federal government. Oddly, none of the opinions provide historical detail on that pivotal subject.

In fact, a closer look at those events shows that the unitary version of a Decision of 1789 is a myth. The first Congress actually rejected Roberts’s interpretation of the Constitution and rejected the strict and exclusive unitary model as well. The constitutional conventional wisdom is a kind of fantasy, an edifice of implausible explanations, built on an obscurantist unicameral legislative history of the sort that textualists, formalists, and originalists like the Roberts majority would otherwise reject. This fable unravels in light of an overlooked diary account of what happened in the Senate and a series of statutes contradicting the unitary theory through the rest of the summer of 1789 and over many decades.

What follows is a deep dive on the first Congress and the true Decision of 1789. It is a cautionary tale about originalism and lawyers’ use of history. It confirms the textualists’ concerns about the cherry-picking of legislative history—yet somehow, the textualists on the Court conveniently rely on this misreading of legislative history. The story is that the first Congress did what legislatures often do: It found the least-common-denominator basis for pushing through legislation by retreating to strategic ambiguity and allowing the proponents to reverse their arguments and explanations when they needed votes. Each side could claim victory.

But, as often happens, one side was better at spin over the long term. These events reveal mostly the complexities of collective decision-making—an example of how Congress is often a contradictory “they,” not an “it.” Refocusing attention from a deliberately muddled legislative debate to the actual statutes that the first Congress passed, it becomes clearer that—if there was any decision of constitutional significance from these debates—it was that Congress had broad powers to regulate, delegate and distribute removal powers.

The fantastical story of the Decision of 1789 goes something like this: When the first Congress was creating the first executive departments, it recognized a gap in the Constitution’s text about who had the power to remove executive officers. A tiny number of congressmen said that the Constitution recognized impeachment and only impeachment as a means of congressional removal. A substantial number (a “senatorial” bloc) argued that the traditional rule was that the removal power mirrored the appointment power—so if the Senate confirms appointments, the Senate must also share a power to confirm firings. The majority, meanwhile, thought that the president alone should have the removal power—what became the orthodox understanding in originalist circles—but this bloc was divided into two factions. One faction (“congressionalists”) thought it was Congress’s discretion to grant this power to the president (meaning that Congress retained the discretion to limit or reclaim that presidential power); another faction (Madison’s “presidentialists”) thought the Constitution itself established this power (and thus Congress had no power to take away this presidential authority).

Here comes the incorrect part of this story. According to the unitary executive theorists, this last bloc prevailed in the House, with Madison crafting language designed to imply that the power originated from the Constitution. Then the Senate split 10-10 on the subject, and Vice President John Adams broke the tie in favor of presidential power. And thus the first Congress confirmed, fixed, constructed or “liquidated”—as various judges, scholars and officials have put it over the years—a unitary executive as a matter of constitutional law. Like Roberts, many lawyers and judges rely heavily on this story to explain why the Constitution shields presidents from congressional limitations on their power.

There’s just one little problem with this founding myth of the unitary executive: The story is wrong. In fact, this story never made sense. But the unitary interpretation really unravels with newly identified evidence from the Senate. The Senate was closed and did not officially record debates. But a senator’s diary recorded a far messier reality: The first Congress actually retreated from the argument that the Constitution vests sole removal power in the president, even for the Department of Foreign Affairs (the equivalent of today’s Department of State) and Department of War (the equivalent of the Department of Defense), which would have been the strongest domains for presidential power. It settled on deliberately vague language instead, because doing so was necessary to get sufficient votes to establish the first executive departments.

The story of what really happened in the first Congress on the subject of removal—and how a mythological version of it became a matter of constitutional faith for conservative jurists—requires getting down in the weeds of some legislative machinations that matter today only because they are being made to stand for a grand principle. These weeds reveal Alexander Hamilton’s flexible political maneuverings and Madison’s sly strategic mind as a legislator. Hamilton, for example, renounced his own contrary views in a dramatic letter for the House audience. And when Madison realized he still did not have the votes for his theory, he dropped the explicit statement of the theory, retreated to strategic ambiguity (a term Rick Hills also uses for the Founding’s drafting strategy when facing tough votes), and somehow pulled off a brilliant sequencing of votes to approve language obscure enough to all sides to pass the Senate. Some of Madison’s opponents on presidential removal power even thought they had won, and some of his allies thought they had lost. But Madison, Adams and Hamilton were better at engaging in pro-administration spin. And the unitary executive theorists have kept spinning this yarn up through the present day litigation over the CFPB, where Roberts, Thomas, and Justice Brett Kavanaugh all buy the myth that this moment established a constitutional precedent that defines the executive branch today.

The following history is adapted from my two papers as part of a book project, “The Imaginary Unitary Executive.” The first paper is “The Indecisions of 1789,” focused on the Foreign Affairs debate sketched above, and the second is “The Decisions of 1789 Were Non-Unitary,” focused on the Treasury Act of 1789 and other statutes giving judges the power of removal. No one doubts the basic point of the unitary executive: The Constitution establishes one president, who is vested with the executive power. The question is how exclusive and absolute that power can be in a system of checks and balances and good faith governance. Ethan Leib, Andrew Kent and I had touched on some of these questions in our 2019 article “Faithful Execution and Article II” on the history of limiting officers’ discretion with oaths and good faith requirements, similar to fiduciary duties. Kent summarized our argument in Lawfare in 2018 here. As a next step, Leib and I suggested that “faithful execution” might also mean that a president needed good faith and good cause for removals.

Continuing this work, I started to search the first Congress for the origins of the assumption that a president could remove “at pleasure” or “at will.” Both Taft and, years later, Kavanaugh—then an appellate judge—claimed that this “at will” rule was part of the Decision of 1789, the central question in Seila. In fact, Kavanaugh wrote in the lower court ruling against CFPB, “In 1789, the First Congress confirmed that Presidents may remove executive officers at will.” Taft made a similar assertion in Myers.

As I started digging, however, I first found no evidence of such a rule, and then it became clear that Congress had arrived at no constitutional decision about removal in general. And as I kept digging, there was more evidence that the first Congress (and later Congresses) actually rejected the unitary theory, even in the domains of war and peace. This article covers only the myth of a great decision in 1789.

The Myth Making From 1789 to 2020

Let’s start with how this legislative debate became known as the Decision of 1789 and endowed with constitutional significance in the first place. If history is written by the victors, constitutional history is sometimes written by the presidential victors and their allies. Both Madison and Hamilton made reversals from their anti-unitary positions in the Convention (Madison) and the Federalist Papers (Nos. 39 and 77) once ratification shifted to governing, and they were insiders in 1789, allies of the new president. Vice President Adams himself wrote in a letter two months after the events in question that his “Vote for the President[’]s Power of Removal, according to the Constitution, has raised from Hell an [sic] host of political and poetical Devils.” A pair of other letters from senators in 1789 offer the same interpretation. Chief Justice John Marshall had a mixed record, and it’s important to note that all parties in Marbury v. Madison took it for granted that President Jefferson or his officers could not remove Marbury from his five-year term, and Marshall explicitly acknowledged Marbury’s job security from removal. (An excellent recent paper explains more here.)

In the 1820s, there was a shift toward more centralized presidential power—and, perhaps in hindsight, more emphasis on the first Congress. In 1820, Congress passed a new statute that broadly granted the president the power to remove “at pleasure” for essentially the first time. A few years later, prominent judges and treatise writers James Kent and Justice Joseph Story adopted the interpretation that the first Congress made a decision expressing constitutional meaning. The first official uses of the phrase “Decision of 1789” were in Congress in 1834 and 1835, most famously by Sen. Daniel Webster in rejecting the claim that the decision settled the constitutional question. Webster instead claimed that the decision was merely congressional delegation and practice, not constitutional permanence.

The term was used more frequently thereafter, but Congress eventually followed Webster’s advice and reversed the decision in a Reconstruction showdown with President Andrew Johnson. In a battle with Johnson over the trajectory of Reconstruction and the continued service of department heads appointed by President Lincoln, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, which required Senate agreement for removals. Johnson’s defiance of this act was one of the central impeachment charges against him.

Congress added the Senate-empowering provisions of the Tenure of Office Act to other statutes over time, so that the removal power was generally nonunitary from Reconstruction through 1926—when former president and then-Chief Justice Taft wrote Myers v. United States, the first time the Supreme Court used the term the “Decision of 1789.” In ruling in favor of presidential power, former President Taft discussed the Decision of 1789 in a remarkable 20-page section that contained a number of historical misunderstandings and oversights.

Nine years later during the New Deal, a conservative Supreme Court in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States upheld (unanimously) a congressional requirement of “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office” for the president’s removal power over independent agencies. This pair of cases has established our current balance of “at pleasure” removal power over regular executive offices and limited removal power over independent agencies.

The term “unitary executive” also emerges in the 1920s, but it was apparently not used to describe the Founding era until the 1940s, and the phrase was not used widely until the 1980s. Why the 1980s? During the Reagan era, conservative politicians and scholars sounded a handful of themes that remain familiar today: The courts were too elitist. Congress was ineffective. The New Deal administrative state had grown too large and too independent. Beltway-insider bureaucrats were out of touch with the public, and needed more centralized presidential power to rein them in. A Cold War demanded a strong presidency. It was attractive to see these perspectives in the Founding, and to imagine a singular president as the democratic representative of the American people during times of crisis.

But let’s first go back and take a close look at what actually unfolded in the House in 1789. Then let’s move to the Senate. The first examination shows that members at the time understood themselves to be leaving the matter strategically ambiguous, and that roughly two-thirds of the House actually rejected the constitutional claim now attributed to them. The second examination involves a diary that further documents the gambit of “strategic ambiguity” and the bill’s proponents explicit retreating from any constitutional meaning.

The House Vote

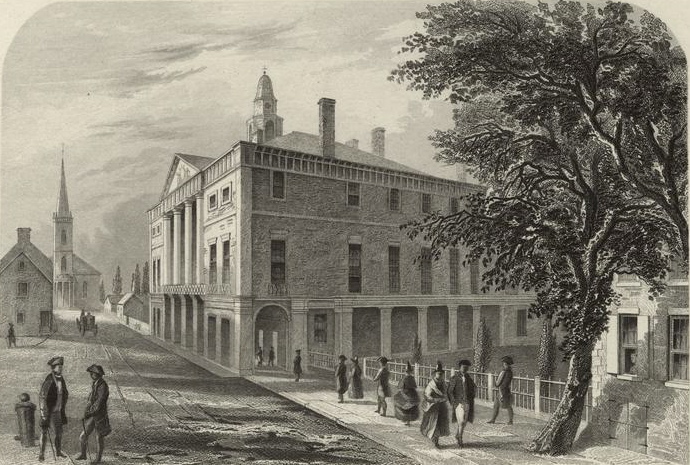

The summer of 1789 was a momentous time in early American political history. The first Congress drafted the Bill of Rights, confronted difficult fiscal challenges, brought a new government into existence, and created the first three departments: Foreign Affairs, War and Treasury. In the Foreign Affairs debate in June, the House first decided that the president had the power to remove officers, and did not need a parallel Senate de-confirmation vote to do so. The first draft of the bill explicitly stated that the secretary of foreign affairs was “to be removable by the president.”

But then the House replaced this clause with an ambiguous backup plan in case of removal: a clause designating that the chief clerk would keep all departmental papers “whenever the said principal officer shall be removed from office by the President or in any other case of vacancy.” Then-Rep. Madison and the other sponsor of this change, New York’s Egbert Benson, explained that the earlier explicit language was not explicit enough: It risked implying that Congress, not the Constitution, was the source of the removal power.

This new language (“whenever … removed … by the president”) could have signified many contingencies: What if a president asserted his own power to remove, regardless of Congress? What if the courts recognized this power or a future Congress declared it? The inclusion of “any other case of vacancy” (such as death or disability) indicated that the clause was neutral on the contingencies, not an endorsement. It is unclear how they thought this language implied that the president should have this power, let alone the source of such a power.

Instead of resolving the confusion with more clarity, Madison and Benson proposed this new contingency plan with even less textual clarity, ostensibly in order to imply that a constitutional power preexisted Congress and derived from the Constitution itself. Their plan succeeded in three separate votes: Step one involved the insertion of the “implied” power; step two involved the deletion of the explicit power; and step three involved the passage of the bill.

Even though Madison’s and Benson’s faction was only one-third of the House, they were able to push through this language through several steps. The first step, which involved adding the contingency plan in case of removal, brought together the “presidentialist” and “congressionalist” blocs to form a majority. The second step, which involved deleting the explicit grant, brought together strange bedfellows, the “presidentialist” and “senatorial” blocs, for opposite reasons (the presidentialists were deleting an implied congressional power; the senatorials were hoping to delete the presidential power altogether). The third step, which required passage of the bill with no explicit grant but just an ambiguous contingency plan, brought back together the presidentialists and congressionalists, who preferred a Foreign Affairs department with an obscure and confusing clause rather than no department at all. And after many days of debate, it would be time to settle for an acceptably ambiguous compromise and move on.

Madison and Benson never announced this strategy, of course. Their explanation for needing to replace the explicit removal power clause with an oblique and obscuring clause never made a great deal of sense. If their point was to signal that the removal power came from the Constitution and not from Congress, why did they not just draft an explanatory clause and say that? Their House opponents openly mocked them for their retreat, and their House supporters soon regretted their failure to retain the explicit statement.

Counterintuitively, Madison announced that the earlier language—“removable by the President”—had the ambiguity problem, because it created a doubt about whether the Constitution or Congress was bestowing the power. Thus Madison said he “wished every thing like ambiguity expunged, and the sense of the house explicitly declared.” The new language “fully contain[ed] the sense of this house upon the doctrine of the constitution.” Never mind that the new language was even more ambiguous about the existence of a removal power at all, and never mind either that this ambiguity further obscured the basis for this suddenly ambiguous power.

It was a dramatic about-face on Madison’s part. A week earlier, in support of the explicit removal clause, Madison had argued that Congress had a duty to speak clearly to give future officeholders fair notice. Over four days in mid-June, the House had fought over a clause that explicitly granted the president the power of removal with Madison leading the charge in favor of the clear language.

But then, after the weekend, Madison reversed himself and abandoned that commitment: The new clause was no “dereliction of the principle” and “had no other effect than varying the declaration which the majority were inclined to make,” he said. To the contrary, it had the obvious effect of abandoning the explicit statement that the removal power belonged to the president in favor of confusion.

What had happened over that mid-June weekend? Is it more likely that Madison suddenly thought a roundabout constitutional signal was more important than clarity and notice? Or did he find out that he did not have the votes in the Senate, and perhaps find a way to thread the needle?

The opponents of a presidential removal power mocked this move from the clear to the ambiguous as a dodge. Rep. John Page, who denounced presidential removal power as “monarchy” and “tyranny,” noted that the majority was “shifting the ground in the matter now proposed, the journal would not declare truly the question which had so long been contested.” Smith, the advocate of the impeachment-only position, taunted the majority for conceding the “impropriety” of their explicit removal clause, though they were “not willing to relinquish openly their principles …. Will they pretend to carry their point by a side blow, when they are defeated by fair argument on due reflection?” Smith further ridiculed them: It would have been “more candid and manly to do it in direct terms than by an implication like the one proposed.”

Rep. Theodore Sedgwick, a congressionalist, said that keeping the original clause with an express power “could do no harm,” but with Madison’s and Benson’s new ambiguous clause, “we have a weak, decrepit explanation, which the president may not easily understand …. [H]e can hardly draw authority from your law.” Some opponents of presidential removal power celebrated the switch as a surrender. James Sullivan, a Massachusetts politician, wrote to Rep. Elbridge Gerry, who had opposed Madison’s moves: “I rejoice with joy unspeakable and full of security, that the point is carried [against] giving the President the power contended for.” He identified their opposition as the “antimonarchical party.” Key supporters of executive power like Fisher Ames doubted their gambit a few weeks later, wondering if they had “blundered” by not keeping the clear language.

Why didn’t Madison and Benson use a preamble or a “whereas” prefatory clause to explain their constitutional purpose clearly and have a vote on that language, rather than leaving the matter ambiguous? Their decision not to include a preamble or prefatory clause is inconsistent with legislative practices of the time, and inconsistent with their own practice at that time. The Framing generation not only used a preamble in the Constitution, but regularly prefaced early statutes with preambles and “whereas” clauses to explain the purpose or background of a clause or statute. The first Congress included such explanatory clauses in many bills. Madison did not write the Preamble in 1787, but he and George Mason were the lead drafters of Virginia’s 1776 Constitution …[,] which included a preamble with 22 clauses and more than 500 words. The Second Amendment, written in the summer of 1789, also has a famous preamble or prefatory clause. So Benson’s and Madison’s explanation for their abrupt reversal from the explicit to the ambiguous sufficiently contradicts the practices of the 1780s that their rationale makes sense only as a pretext.

In fact, they didn’t have the votes. Only about a third of House votes followed the Madison-Benson presidentialist plan. The advocates of the Decision of 1789 suggest that there is reason to think that the majority who voted for the bill supported the presidentialist view and not the congressionalist delegation view. But the math does not work: The statements in debate, especially on the key day of the decisive vote on Madison’s plan, show that a majority of the House did not share his view, even if they wound up passing the Foreign Affairs bill with his ambiguous language. Even after adding all the silent “no” voters that one unitary scholar, Saikrishna Prakash, calls “enigmatic,” the math still does not work. At most, Madison lost 23 to 28, but it was likely closer to 16 to 35, a decisive loss hidden by his strategic cycling of votes. (Justice Louis Brandeis and others have suggested that the presidential view did not have a majority, but no one has ever analyzed the votes plus the debates to create a member-by-member assessment of the size of each bloc, though “The Contested Removal Power” produced a helpful table identifying the “enigmatic faction.” My table breaking down the blocs more precisely is at the end of this paper.)

Prakash suggests that even if the “enigmatic” members’ voting patterns did not line up with the Madison/Benson plan, perhaps they were quietly presidentialists who wanted explicit statements: They voted for the ambiguous contingency plan language (yes on step one) and to keep the explicit removal language (no on step two) because they wanted presidentialism with a more explicit removal statement.

But this argument is ironic and self-defeating. It would be quite an irony if these silent members believed it was necessary to be clear and explicit to convey constitutional meaning, and yet never proposed any language to fully clarify the matter or even articulated this concern. But it is even more incongruous to construct permanent constitutional meaning out of silence. It is hard to derive the strongest possible constitutional “Decision” from silence, when simply pragmatism or uninterest seems a more likely explanation. The summer of 1789 had a mammoth legislative agenda, and the legislative session was almost half over with Congress having completed almost none of its work. Why should scholars and judges assume the silent were trying to make some grand statement, rather than just a lack of interest in constitutional theory and keen to move on?

What’s more, when the chips were down on the decisive day of Madison’s proposal (Monday, June 22), the six “congressionalists” explicitly and unequivocally opposed the presidential interpretation. A leading congressionalist at the start of debate announced that a vote of “no” on the second step should be interpreted as a congressionalist/anti-presidentialist vote. One member disagreed as he explained his own vote, but as others were silent as they voted “no,” it seems likely that they were following the six vocal congressionalists.

Prakash’s argument actually exposes a contradiction: If this “enigmatic” bloc of seven was voting against Madison’s proposal because it was too unclear, how can original public meaning be constructed from a text that the key votes in the House at the time thought conveyed unclear meaning to the public? Madison’s own theory of “liquidation,” after all, depends on clarity of such decisions. The unitary scholars cannot have it both ways: It cannot have been so unclear that it explains some “enigmatic” votes, but also clear enough to have permanent constitutional meaning.

Once one rereads the House debate, the reasons for abandoning clear language are no longer enigmatic. The move was strategic—precisely because members knew that the Senate opposed this power. The final speaker before the key vote on June 22 was John Vining of Delaware. His first point was unsurprising for such a vocal presidentialist: He “[a]cquiesced in striking out; because he was satisfied that the constitution vested the power in the president.” But his second point was a remarkable tell, an explicit reference to getting the bill through the Senate: “[H]e thought it more likely to obtain the acquiescence of the senate on a point of legislative construction on the constitution, than to a positive relinquishment of a power which they might otherwise think themselves in some degree intitled to.”

Vining, a core member of the presidentialist bloc, was saying the quiet part out loud. The ostensibly permanent constitutional conclusion, designed to cut out the Senate, would also be more likely to win “the acquiescence” of the Senate due to “legislative construction,” because it actually was not a “positive relinquishment of a power.” This was the strategic ambiguity for a skeptical Senate, and perhaps also a confession and a concession.

The Senate and Maclay’s Diary

The Senate has always been a formal problem for the unitary executive advocates of the Decision of 1789: The Senate had no official legislative record in this era, and the Senate’s objections and its 10-10 tie vote on any kind of presidential removal power indicate no consensus. Not only is it a textualist’s faux pas to rely on legislative history to derive meaning of an ambiguous statute, it is a formalist’s blunder to rely on a legislative history of only one chamber of Congress. Justice Antonin Scalia and the Supreme Court have rejected unicameral lawmaking, but the formalistic unitary executive theorists somehow rely on a unicameral legislative history in drawing great meaning from a House vote with which the Senate concurred only in the most minimal fashion—a tie-breaker, with no evidence of how many “yes” votes were presidentialist vs. congressionalist.

But now there is yet an even bigger problem: A diary, it turns out, records a version of the Senate debates, and those debates cut strongly against the unitary executive theory. Sen. William Maclay’s famous diary from the day of the final Senate vote on the Foreign Affairs bill indicates, first, that two swing votes for the bill were tepid, and likely logrolling with no constitutional view on the matter; and second, the Senate’s proponents of the bill said that the clause was insignificant, offered to drop it, disclaimed the House authors’ intended meaning and even seemed to deny that it gave exclusive removal to the president at all. The Senate opposition explains why the presidentialists were trying to replace the explicit with the ambiguous.

Maclay’s diary shows why Benson and Madison took these risks of ambiguity. If they suspected that the explicit language would kill the bill in the Senate, they may well have been right. This ambiguity was a feature, not a bug, for getting the bill passed. House presidentialists could claim one meaning, and then the Senate presidentialists apparently could deny it. Maclay’s diary notes that Vice President Adams broke a 10-10 tie on the bill on July 16 and again on July 18 to preserve presidential removal power. The initial head count appeared to be eight for, 12 against—until two late switches, allegedly due to logrolling, produced a tie vote.

The diary reveals that the Senate’s sponsors of the bill played out the strategy of ambiguity and denied that the House was cutting out the Senate. Maclay suggests the bill intentionally used ambiguity in the contingency clause to hide the bill’s effect of disempowering the Senate: “The design is but illy [sic] concealed.” Maclay was a Federalist, a lawyer, a judge and a former state legislator. He was respected enough to be assigned to the Senate committee that drafted the Judiciary Act, one of the few major bills that the Senate took the lead in drafting. He also was eccentric, difficult, cantankerous, vain, insecure, and a bit paranoid, and he loathed Adams—so his diary must be taken with a grain of salt.

That said, Maclay’s account is also the only detailed journal of the Senate in these years. Even if there are some exaggerations or inaccuracies, the basic account does not raise suspicions that he was writing a fabrication intended for publication and designed to undermine the meaning of this vote or otherwise embarrass anyone. Maclay never revealed his diary. When he died in 1804, his diaries were unknown and hidden. Eventually, his nephew found them and sought to publish them—but it took about a century to get them published, and thanks to the wonderful First Congress Project, it has been on seminar syllabi for at least two decades. That’s how I read it in Professor Joanne Freeman’s graduate seminar in Spring 2000. It seems Maclay went to his grave expecting his diaries to remain private. Scholars rely on Maclay’s diary for the history of the Judiciary Act of 1789, so it seems reliable enough for the Foreign Affairs Department debates, too.

Maclay records that Senate debate on the Foreign Affairs bill began on July 14. Maclay records that the bill seems to have been in trouble, but the next day, Maclay noticed senators “caballing and meeting” in knots, “a General hunt and Bustle …. [I]t seems as if a Court party is forming.” The next day, two senators who had been opposed to the removal clause suddenly announced a switch in favor, which Maclay ascribed to “the Court party in procuring Recantations or Votes” and “buying Members.” Let’s set aside Maclay’s bribery suspicions; his account suggests there was never an enthusiastic Senate majority about this clause.

Even after several days of debate, on the final day of debate the Senators were still wrestling with the basic meaning of the text. Johnson, an early critic of the bill's "Quest[ionabl]e shape, and Maclay both were still trying to clarify whether the bill in fact excluded the Senate. Maclay's speech only makes sense if Senators were still debating this effect and still confused by the ambiguity. After pointing out how it was obvious that the clerk would take care of the department papers in case of any removal, Maclay asked rhetorically, "What then is the Use of the Clause?" Apparently he felt this point still had not been clarified: It was to empower the president. He concluded, "the design is but illy concealed."

Perhaps perceiving that the Senate vote could tip back against both the clause and the entire bill, its supporters immediately suggested compromise and even deleting the clause. Sen. William Paterson had been one of the primary advocates for the bill: “Patterson got up, said the later part of the clause, perhaps was exceptionable [open to objection or reasonably objectionable], and he would have no objection to strike it out. Mr. Morris rose and said something to the same import.” It is possible to read this passage as Paterson and Morris striking out either the full last sentence, thus deleting removal; striking the phrase about the president; or striking out just the last half of the sentence, but that would have left only an incoherent sentence fragment. Again, Maclay's diary should be taken with a grain of salt, and one should be careful drawing too much meaning from fragmentary legislative histories or diaries. But in any of these possibilities, the supporters of the bill were retreating from the convoluted way the bill had been drafted after Maclay pushed his criticism that the clause was "nugatory," "unclear," and "illy concealed" its anti-Senate "design." Instead of adding clarity, the bill's proponents proposed more confusing deletions. Maybe the senators were bluffing, but they appeared willing to sacrifice the removal provision to save the rest of the bill. Apparently these senators did not think it was so important to convey removal power, whether constitutionally- or congressionally granted.

Sen. William Johnson, also an opponent of the bill, “glanced somewhat at the conduct of the other House, and as what I had said leaned the same way.” According to Maclay, Johnson was issuing the same warning that Maclay had, that the House sponsors had said they intended this wording of the statute to mean removal was only the president’s power, and not the Senate’s. Robert Morris, the former powerful superintendent of finance and a supporter of executive power, rose to answer: “Mr. [Robert] Morris said whatever the particular view might be of the member who brought in this clause, he acquitted the House, in general, of any design against the Senate.” Morris meant that the House authors’ intent was irrelevant, and even so, he denied that the House had “any design against the Senate.” Maclay added, “Mr. Elsworth rose and said much more on the same subject.” Elsworth had been, according to Maclay, a theatrical advocate of presidential removal power.

Maclay then recounted his final speech, which apparently preceded the final vote of a 10-10 tie, broken by Vice President Adams. Maclay is sharply suspicious that the bill’s advocates were dishonest, hiding the same power in “cloaked” language. Just as the House’s skeptics denouncing Madison’s move as a “side blow,” Maclay called it a “side wind,” the opposite of “plain dealing.”

Soon after passing the Foreign Affairs bill, the Senate voted 10-9 in favor of the removal power for the War Department. In the Treasury debate, the Senate vote shifted back against removal, and it deleted the bill’s presidential removal section. The House did not back down, and a month later, the Senate voted 10-10 again, and Adams’s tiebreaker meant the Senate passed the House version with the removal power.

The senators on both sides may have been relieved not to have to vote on an explicit statement. Both sides could claim victory, though they knew it was just a compromise and an excuse to move on. It is plausible that the House’s presidentialists knew many senators were already unsupportive of getting cut out of the removal power, and the ambiguous language was an attempt at a backdoor compromise. It is also plausible some of them had quietly negotiated back in June with the House leaders like Madison and Benson to drop the explicit clause.

Once it is clear that the first Congress could not even agree that the Constitution establishes a presidential removal power—not even for the forerunners of the secretaries of state and defense—it is not surprising that the first Congress did not come close to endorsing presidential removal “at will” or “at pleasure.”

There’s another piece of evidence: Chief Justice Roberts overlooked how Madison’s proposal for the comptroller in these debates in the summer of 1789 was for tenure during good behavior, precisely to create a Treasury official more independent from the president. But more surprisingly, the first Congress went on to reject the unitary idea of exclusive presidential removal with concrete legislation, explained as an anti-corruption measure.

Exclusivity is necessary and fundamental to unitary arguments. Roberts’s and Scalia’s opinions, for example, assert exclusivity to limit Congress’s power over removal conditions. In Bowsher v. Synar, the Supreme Court held that non-executive offices may not exercise executive powers. Likewise, lawyers on behalf of President Trump recently relied on exclusivity to argue that presidents are immune from congressional oversight and subpoenas.

And yet the first Congress gave removal power over executive officers—even principal officers— to judges and juries in the Treasury Act of 1789, and in four other statutes. Congress extended removal-by-judiciary in at least 15 other statutes before 1820, and even more thereafter. Some of these statutes were specifically in the domain of foreign relations and war, like the Neutrality Acts, the Alien and Sedition Acts, the Logan Act and the Embargo Acts. Congress, in other words, was empowering prosecutors and judges to remove executive officials, with or without the support of the president. The first Congress and many Congresses after it thus rejected the notion that the president has exclusive removal power.

The Bottom Line

Those making originalist claims bear a burden of proof to show a clear public meaning circa 1787. For those claiming that Article II requires presidential removal at will, this burden is especially difficult in the face of textual silence, more than a century of legislative practice and almost a century of judicial precedent. First and most fundamentally, this new historical evidence and interpretation show that it has been an error to rely on the Decision of 1789 to overcome the Federalist essays by both Madison and Hamilton. Second, the evidence from 1789 actually points in the opposite direction, a decision against unitary structures.

There are several immediate ramifications of this. It is important to recognize that the key precedents for presidential removal power rely on historical errors. One can still construct a presidential removal power from a structural argument, the Vesting Clause, and the Take Care Clause. But this more open-ended basis of removal means a less formal rule of separation of powers, with more balance with other constitutional texts and values: the Necessary and Proper Clause, the “faithful execution” clauses, and the fundamental principle of checks and balances. The convention, the ratification, and the first Congress all show that Congress has the power to set reasonable conditions on presidential power—so long as they do not functionally undermine a president’s ability to execute the laws. Under this reasoning, for example, entrenching a bureaucracy in order to obstruct an incoming administration—like a Midnight Judges Act of 1801 but for the administrative state, to create something like a deep state or deeply burrowed state—could be an unconstitutional intrusion on the executive power.

So does the CFPB structure undermine a president’s ability to execute the law? This more accurate account of 1789 does not dictate a different result in Seila Law. An anti-unitary first Congress does not necessarily save the structure of the CFPB. The point is that the more appropriate analysis is functional, not formalistic, in part because the approach in 1787, 1788, and 1789 was functional, and not formalistic. One could reasonably draw from the text and structure of 1787 and a century and a half of institutional and judicial precedent to conclude that the CFPB structure functionally goes too far, but it seems like the question may turn more on how a particular CFPB director would use this power, and whether “inefficiency, neglect of duty, and maladministration” should be interpreted to allow a president to remove an obstructionist director, rather than a director with a disagreement over policy.

In a related case invoking the unitary theory, Trump’s lawyers relied on similar arguments and the same precedents to contest congressional and state prosecutor subpoenas. The Decision of 1789, properly understood, is no basis for such an argument, and in fact, the first Congress’s votes and enactments militate in favor of congressional oversight of finance, the treasury and national security questions.

It is precisely for the purposes of anti-corruption and investigation that Madison proposed—and the first Congress actually enacted—nonunitary checks and balances on presidential power. The courts and Congress should heed the Founders’ foresight by protecting expertise and independence within the executive branch. Moving forward, Congress and the courts should be able to engage in meaningful reform to strengthen the independence of the Justice Department, the inspectors general and other offices. Courts should permit Congress to engage in external checks and balances to strengthen internal checks and balances within the executive branch. Given Roberts’s ruling against the single-head CFPB, Congress might design a new model of inspectors general commissions, protected with “for-cause” limits on removal, but not so independent as lone rangers in a department. A commission structure would take presidents and precedents seriously, and it would value the historical evolution of independence within the executive branch. The Supreme Court would threaten such reforms only if it clings to an ahistorical interpretation of the Founding—a unicameral legislative history, an erroneous legislative history, an anti-originalist imagined unitary executive of the 1980s, not the 1780s.

Correction: This piece has been edited to more accurately reflect the ambiguity of portions of Sen. William Maclay's diary regarding the proposed deletion by Sens. William Paterson and Robert Morris.