Independence and Accountability at the Department of Justice

Over the weekend some conservative commentators pushed back on my tweet-claim that President Trump has “threaten[ed] DOJ/FBI over and over in gross violation of independence norms.” The Justice Department and its component the FBI “aren’t independent, nor should they be,” argued Sean Davis of The Federalist.

Over the weekend some conservative commentators pushed back on my tweet-claim that President Trump has “threaten[ed] DOJ/FBI over and over in gross violation of independence norms.” The Justice Department and its component the FBI “aren’t independent, nor should they be,” argued Sean Davis of The Federalist. “Few things are more damaging to a democratic republic than men with guns and badges and wiretaps believing they are accountable to no one,” he added. Or, as Kurt Schlichter of Townhall stated more succinctly, “When did bureaucrats become ‘independent’ of elected officials. Never.”

Davis and Schlichter are wrong about DOJ and FBI independence. For better or worse, these institutions are in important respects independent of the President. But I agree with Davis that it would be a disaster if the DOJ and FBI were unaccountable. Fortunately, they are not. Seeing how the DOJ and FBI can be partially independent of the President and yet deeply accountable at the same time puts current events—the Russia election investigation, the Nunes Memo, the lurking Inspector General report, Trump’s attacks on the DOJ and FBI, broader allegations of DOJ and FBI malfeasance, the possible indictment or impeachment of the president, and the like—in a more understandable light. Unfortunately it takes many words to do so.

I. Independence from the President

For those who believe in a unitary executive, DOJ/FBI independence is a constitutional solecism. On this view, Article II vests the “executive power” in the President alone, and he alone wields it. That means that the President can do what he likes with his Executive branch subordinates—hire them, fire them, ignore them, order them to act in certain ways, and the like. The presidential authority to direct and control an administration is especially clear with respect to law enforcement and national security, the story goes, since the President himself has a constitutional duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” and is the “Commander in Chief.”

This is a nice theory. Sometimes (though not often) I wish that it were so. But the theory has been repudiated in law, and especially in practice, for a long time. There are far too many examples to cover, but here are a few relevant ones. The President can generally fire his political appointees at will, though the Supreme Court has long upheld certain statutory limitations on the President’s removal power (including in the context of the Clinton-era independent counsel statute). The FBI Director’s ten-year term—through which Congress signaled that the Director has independence from electoral politics—raises the political stakes for a President who fires an FBI Director mid-term, as President Trump learned last year. And career civil servants below these senior political appointees (like just-retired FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe) have extensive legal protections against presidential firing.

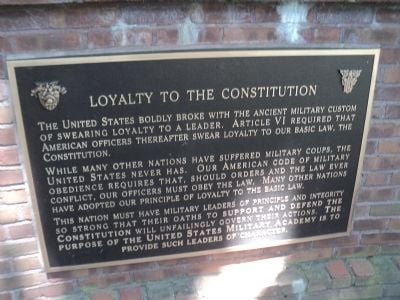

Those are the main “legal” guarantees of DOJ/FBI independence. They are very few, and they are not the most important. The most important guarantees of DOJ/FBI come not from the Constitution or statutes, but from norms and practices that since Watergate have emerged within the Executive branch.

Every presidency since Watergate has embraced policies for preserving DOJ and FBI independence from the President in certain law enforcement and intelligence matters. These internal regulations and memoranda, and the norms they foster, acknowledge the President’s ultimate power and responsibility for law enforcement and intelligence while at the same time recognizing that in certain matters, the Executive branch needs internal divisions of authority that achieve a type of independence from presidential control. One example is the restrictions that every administration from Carter to Trump has placed on communications between DOJ (including the FBI) and the White House concerning law enforcement investigations and other matters. Another is the Special Counsel regulations that govern Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s conduct and termination.

When Trump wanted Mueller gone last summer, he did not issue the order himself, as the unitary executive theory would suggest. He told White House Counsel Don McGahn to make it happen, but McGahn “refused to ask the Justice Department to dismiss the special counsel, saying he would quit instead.” McGahn would have had to ask DOJ to dismiss Mueller because the relevant statutes and regulations gave the control over Mueller’s termination to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, not Trump. Rosenstein, in turn, is hemmed in by law and especially regulations in his ability to fire Mueller. The situation never got this far, but Trump could have fired Rosenstein if Rosenstein had failed to carry out an order to fire Mueller or to alter the relevant regulations. And yet the need to go to DOJ to accomplish these acts, and the political costs of having to fire an insubordinate DOJ official (and possibly the White House Counsel), are checks on the President and a form of DOJ independence. (Compare the Saturday Night Massacre, where it took two high-profile DOJ resignations to terminate Cox, which only resulted in the appointment of an equally assiduous Special Prosecutor, Leon Jaworski.) The point generalizes: The President acts through his appointees, and can ultimately get his way only if he can find appointees willing to do what he wishes. This is sometimes not possible to do without adverse political consequences.

A related check on the President that has been developed and nurtured as a result of these post-Watergate regulations and practices are the cultural self-understandings of DOJ and FBI officials, including (many) political appointees. These men and women share a professional and departmental commitment to the rule of law, one component of which is resistance to politicized influence by the President on their operations. That seems squishy and possibly even dangerous. When the President and DOJ are in conflict, it is not always easy to tell whether DOJ is acting on the basis of the rule of law or some self-serving bureaucratic imperative, or whether the President’s influence is an appropriate exercise of Executive discretion or a “politicized” action that should be resisted. Any bureaucracy, including in DOJ and FBI, can use independence as a shield to frustrate presidential (and thus democratic) control over policies that fit within the President’s legitimate priorities. This is an old and inevitable problem of administrative governance. Some presidents manage it better than others, especially through the wise selection of political appointees to run the bureaucracy. The important point for now is that these institutional self-understandings are a real force for independence, even on political appointees, as the various threatened resignations by Trump’s political appointees in the DOJ and FBI in response to Trump’s attacks show.

A final example is the Inspector General (IG) at the Justice Department. As I explained in Power and Constraint:

In 1978, as part of its post-Watergate resurgence, Congress gave them extraordinary functional independence within the executive branch and made them more beholden to Congress. These new “statutory IGs” are confirmed by the Senate and must report semiannually to Congress. They have access to all records and information inside the relevant agency and full power to launch investigations, issue subpoenas, and refer criminal wrongdoing to the Justice Department.

The DOJ IG has a large degree of de facto independence from the President (and from other executive branch officials, including the Attorney General and FBI Director). Even though the President can remove the IG, he must report to Congress why he does so. Despite the President’s termination power, the IG’s power to initiate and carry out an investigation on practically any matter of relevant interest is significant. Congress has the IG’s back like no other official in the Executive branch, which led a group of experts in 1998 to describe IGs as “congressional ferrets of dubious constitutionality.” But today, and despite unitary executive theory, IGs are established features of the executive branch landscape. It would be politically costly for a President to fire an IG investigating a sensitive matter without good cause, especially if the President aimed to suppress criticism.

If you doubt the extraordinary power of the DOJ IG, then I have two words for you: Michael Horowitz. Horowitz is the DOJ IG and the author (among other Obama-era reports) of the very long and critical 2012 “Fast and Furious” report. For over a year he has been investigating how DOJ and FBI handled the Clinton email investigation (including an analysis of the Peter Strzok and Lisa Page text messages, which he recovered after the FBI lost them), and possibly the circumstances, at least within DOJ, of Trump’s firing of Comey.) Horowitz is operating entirely outside the effective control of the President. He has been in communication with Mueller about their overlapping investigations, and has pledged to “hold in abeyance any activity while there’s an ongoing FBI or in this case special counsel investigation,” whatever that means. But his draft report has already had a big impact (as we shall see below), and is sure to be cataclysmic when issued this spring.

So Davis and Schlichter are just wrong when they say that DOJ and FBI are not independent. In practice, as Donald Trump has learned to his colossal frustration, DOJ and FBI are in many respects quite independent. This doesn’t fit with theoretical claims for the unitary executive. But it is a reality of American constitutional governance in 2018, and it has been for quite a while.

Some presidents manage this independence better than others. What Arthur Schlesinger Jr. said of presidential control over the administration applies to DOJ and FBI: “The power to manage the vast, whirring machinery of government derives from [a president’s] individual skills as persuader, bargainer, and leader.” Donald Trump is not skillful at persuading, bargaining with, or leading his administration. Nor does he inspire trust or admiration in his troops. He acts like he doesn’t care about law and has no respect for DOJ, FBI, and their pursuits. When Trump acts this way, he makes it harder for the DOJ and FBI to engage in appropriate accommodations to him at the margins, since any normal accommodation or deference looks like caving. Trump’s off behavior is of course his prerogative—which he has been exercising, to his detriment, since his presidency began.

II. Accountability

While Davis is wrong about DOJ independence, he is quite right about accountability. It would be a disaster if FBI officials “with guns and badges and wiretaps” were unaccountable to anyone, or believed they were. The FBI and its parent the DOJ are vitally important institutions. But they have no monopoly on virtue. They sometimes suffer from the pathologies that plague all government organizations, including myopia, abuse of power, bad judgment, and others human and organizational failings. This is why we need accountability for these institutions. Accountability is, in Edward Rubin’s fine definition, “the ability of one actor to demand an explanation or justification of another actor for its actions and to reward or punish that second actor on the basis of its performance or its explanation.” An accountability system aims to control such organizational failings by forcing the organization to reveal what it is up to so that other institutions can assess it and try to alter its course, or at least raise its costs of action going forward, if they don’t like what they see. One argument for the unitary executive is that the President needs to control all executive action because he and the Vice President are the lone elected officials in the executive branch. To the extent that DOJ and FBI are independent of the president, we should very much worry about who’s guarding the guardians.

But the idea that DOJ and FBI are not accountable is absurd. Many guardians watch over them, seek information, and impose or threaten costs if they don’t like what they see. Consider some of the ones that apply to the DOJ/FBI investigation of the Clinton emails and Russian interference in the election.

First is the President. Despite the independence principles listed above, Trump retains subtle levers, most of which he is not wielding, to influence DOJ and FBI, even in areas related to law enforcement. The President also has some unsubtle powers. He can still fire political officials, including Sessions, Rosenstein, and Wray, at will. There are hurdles and constraints and costs to doing so, all political. But at the end of the day the President can remove these officials if he does not approve of their performance. The President also has other tools to shape an investigation. For example, the President is in charge of classified markings for the government, and will decide on whether and with what redactions or restrictions the Nunes memo will be released.

Second is the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), which DOJ/FBI must convince before gaining a warrant for foreign intelligence surveillance of matters related to the Russia investigation. Critics won’t be convinced (and shouldn’t), but DOJ and FBI take super-seriously the evidentiary and legal requirements for a warrant. That, and not FISC rubber-stamping, is why such a high percentage of warrants are granted. The same goes for ordinary federal courts that approve warrants in criminal investigations These institutions stand as an important watchdog on the DOJ and FBI, including Special Counsel Mueller.

Third is Congress. Many have been disappointed in Congress’s performance in checking the president in connection with the Russia investigation. I would give it mixed grades, especially since politics never suddenly stop when Congress investigates a president. But the point for now is that the Congress has been undeniably vigorous, as it should, in overseeing DOJ and FBI’s pursuit of the Russia investigation. It has already had two long public sessions with Chris Wray about the matter—first at his confirmation hearings, and second by the House Judiciary Committee on December 7. Especially in the December hearing, the committee grilled Wray relentlessly about possible FBI or DOJ political biases and improprieties, and received numerous pledges that Wray would act if is convinced that wrongdoing took place. The Executive branch has also turned over an unusual amount of information to Congress related to the investigation. Devin Nunes himself said that DOJ gave his committee “access to all the documents and witnesses” it requested.

And then there is the Nunes memorandum. This is a fluid situation. I put myself in the camp with those who are suspicious of Nunes’ motives and competence and commitment to fair-minded oversight, based on his performance to date. The manner in which he created his notorious memorandum, and his original threat to release it without Executive branch review, was (as the Trump DOJ noted) “extraordinarily reckless.” That said, the Intelligence Committee is charged with overseeing the foreign intelligence surveillance process and with DOJ counterintelligence investigations more broadly. It has been a dysfunctional and political committee engaged in dysfunctional and politicized oversight. But it has every right to look at the the DOJ/FBI performance, and enormous discretion to report what it finds to the public. The Intelligence Committees are subject to the same pathologies as the executive branch institutions they oversee, and Nunes’s antics have ensured that his committee’s oversight in his context cannot happen in an orderly fashion. And so it will happen in a disorderly way. Publication of the Nunes memorandum may skew our understanding of how the Russia investigation originated and was pursued, at least in the short term. And it will harm U.S. national security if it results in revelation of intelligence means and sources. I don’t want to understate the short-term and possibly medium-term damage that it might do in the current political environment. But while Nunes is exceeding the limits of propriety here, he is also opening himself up to what will be enormous critical scrutiny of his actions. If past is prologue, that will not end well for him. And if past is not prologue, then perhaps Nunes has something to say. We will see. The larger point is that the country will eventually have a full accounting of the operation of the FBI/FISA process related to the Russia investigation, and of representative Nunes’ role.

Fourth is the Inspector General. It is hard to exaggerate how important IG Horowitz is here. Wray in his December House Testimony deflected many questions from Congress about FBI performance in the run up to the election, and related matters, out of deference to the upcoming IG Report. Horowitz’s report will provide a lot of credible information about exactly what went down in 2016 (and possibly 2017) in FBI and DOJ related to the events in the news. Some of the report, it appears, will be damning. “Agents and lawyers expect the report by the Justice Department’s inspector general, Michael E. Horowitz, to be highly critical of some F.B.I. actions in 2016, when the bureau was investigating both Hillary Clinton’s email use and the Trump campaign’s connections to Russia,” the New York Times reported yesterday, in explaining why Wray might have moved to nudge out McCabe earlier than expected. We should all (as Ben suggested) reserve judgment until we see the report. But there is no doubt the report will provide loads of information and effect extraordinary accountability. (Prediction: Horowitz’s report will be a political boon to the President.)

Fifth is the press (and relatedly, government leaks). Every day, it seems, the press discloses new information—not all of it reliable—about the Russia investigation, including the DOJ/FBI role. A good deal of it is critical of the DOJ and FBI. This new and critical information is the fuel that runs everything else, especially political pressure on DOJ and FBI from Congress and the White House. This information, in conjunction with incessant attacks and criticism, have a big impact on the people who are subject to the attacks. They are an important form of accountability.

III. Our Unusual Constitutional Situation

The system I have just described is messy. The President has significant authority over his executive branch but he does not have effective power to shape the Russia investigation as he wishes. The DOJ and FBI have a good deal of independence from the President in conducting the Russia investigation, but they are very far from unaccountable in this endeavor. The President or his aides might have done something wrong in the run up to the election, or in their efforts to slow the investigation of the Russian interference. We have some information on this, but not much reliable information, especially about the President; there will be a lot more forthcoming soon, and there will be consequences. The DOJ and FBI might have done something wrong in their conduct of the investigation into the Clinton emails or the Russian investigation. We have some information on this, but not much reliable information; there will be a lot more forthcoming soon, and there will be consequences. The same is true, though to lesser degrees, of the conduct of the other actors in this play—the intelligence committees, including Nunes; the FISA court; and the inspector general. Some of these actors appear to be behaving badly, as always happens. But in the end, the information will emerge and democratic institutions—juries, perhaps Congress in impeachment proceedings, and ultimately voters in elections, including the midterms in ten months—will decide what happened and what should be done.

None of this is pretty. Much of it may be unfair to the people on the receiving end of harsh judgments and criticisms. A good deal of what is going on is tinged with politics, from all sides. The situation is made all the more unusual because the typical alignment of interests between the President and his law enforcement and intelligence agencies has been shattered, and because Trump incessantly breaches norms of presidential decorum, especially in seeking to discredit the integrity of his administration, including his political appointees. I expect that a lot of damage will be done to all of the institutions involved in this mess before it is over. And that is very bad.

But I also expect that in the end, something approaching the truth will come out, every actor involved will be held accountable in some way, and no major breach of law in connection with the Russia investigation—by the President, his aides, or the relevant officials in DOJ and FBI—will go unredressed. Call it, with apologies to Sandy Levinson, constitutional faith.

-(1).jpg?sfvrsn=ccaf7c0_5)