Indicting and Prosecuting a Sitting President

There are ... incidental powers, belonging to the executive department, which are necessarily implied from the nature of the functions, which are confided to it. Among these, must necessarily be included the power to perform them, without any obstruction or impediment whatsoever. The President cannot, therefore, be liable to arrest, imprisonment, or detention, while he is in the discharge of the duties of his office ...

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, § 1563 (1833)

There are ... incidental powers, belonging to the executive department, which are necessarily implied from the nature of the functions, which are confided to it. Among these, must necessarily be included the power to perform them, without any obstruction or impediment whatsoever. The President cannot, therefore, be liable to arrest, imprisonment, or detention, while he is in the discharge of the duties of his office ...

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, § 1563 (1833)

The late Charles Black and I agreed that a sitting president may not be indicted (see pp. 111-112, 136 in Black & Bobbitt, Impeachment: A Handbook). These conclusions are matters of constitutional law, not departmental policy—though they are confirmed in an Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) opinion—and they are founded on reasons of original intent, text, structure, prudence, and precedent.

I’m very grateful to Lawfare and to Professor Laurence Tribe for an exchange of views that has permitted me to consider not only his objections to my conclusions but also how they might be reconciled with his. This exchange has sharpened some points of disagreement, but it is also highlighted points of overlap and even suggested new proposals on which we may both agree. That is just the way it should be.

I’m not persuaded that it would be wise to modify the rule that sitting presidents cannot be prosecuted, nor am I persuaded that, even in the peculiar circumstances in which the country may find itself should Special Counsel Robert Mueller disclose evidence of widespread criminality on the part of the president, an exception should be made. Hard cases make bad law, and Americans should be very wary of contorting constitutional rules to ensnare a uniquely corrupt official.

Some commentators have concluded that any constitutional rule that would prevent the indictment of a sitting president would have to permit exceptions, citing the hypothetical of the president who shoots and kills someone in plain view. In his Lawfare reply, Professor Tribe even asserts that, “nobody seriously advocates applying the OLC mantra of ‘no-indictment-of-a-sitting president’ to that kind of case.”

But I do. If the president shot and killed someone on Fifth Avenue, I have little doubt he would be swiftly impeached by the House of Representatives and convicted by the Senate forthwith, after which he would be tried for murder. The entire impeachment and trial of Bill Clinton merely lasted from December 1998 to February 1999. It is scarcely uncommon for such a delay to occur between a crime and its prosecution. If Congress has become so degraded that such an impeachment and conviction did not occur, the country would face many more profound problems than that of postponing the indictment of the president.

Moreover, even were I to concede that there might in some extreme case be a convincing cause for creating an exception to the general rule, it’s not altogether clear just how such a prosecution would come about. I doubt that many persons who have reflected on the matter would choose to make a sitting U. S. president subject to indictments by state officials. It casts no slur on the state criminal justice systems to conclude that there are simply too many states’ attorneys—a great many of whom are elected—to avoid the inevitable spectacle of dozens of politically-motivated charges brought against the incumbent in the White House. In such a situation, it is highly impractical to grant every local district and county attorney the power to indict a president who is serving his term of office and thus to plunge the White House into chaos.

But if a sitting president may not be indicted and prosecuted by state officials, who is supposed to prosecute him for crimes while he remains the head of the executive branch and the official to whom all federal prosecutors, without exception, are responsible? Or must there be an exception to that rule too, making the Department of Justice into an independent agency, freed from any decisive guidance by the head of the branch of government of which it is a part?

It is sometimes nonchalantly said that someone other than the president—usually the attorney general—is the “chief law enforcement officer” of the United States; that is a position that is hard to maintain in light of the Constitution’s command in Article II, Section 3 that the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” The Department of Justice and the attorney general are not established by the Constitution. They are created by statute and Congress could abolish them tomorrow. Who would be the “chief law enforcement officer” then?

Now consider, however, this very unusual hypothetical. Suppose a candidate and his associates sought to secure his election to the presidency by conspiring with hostile foreign adversaries and domestic accomplices to pervert the course of the election. Assume further—which I in fact think would be an erroneous assumption (see pp. 89-94, 125-129 in Black & Bobbitt and also Bob Bauer’s excellent essay)—that these crimes are not impeachable offenses themselves. Is there then a constitutional compulsion to wait for four or even eight years during which the president is shielded from being held accountable precisely because these crimes enabled him to win the office of the presidency? Even if I am correct in asserting that such a crime would serve as the basis of an impeachment, suppose the president thwarted the exposure of his crimes through his control of the organs of the federal government, obstructing investigations and corrupting potential witnesses?

This is a form of argument called ethical argument that denotes an appeal to character of American government as reflected in statutes, canonical statements by U.S. leaders, and norms sanctified by centuries of confirmation in practice. One such argument arises from the oft-stated principle that no man is above the law, a principle enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and elsewhere.

As a veteran of the Lewinsky-inspired impeachment proceedings against President Clinton—I was working at the National Security Council the entire time—I confess I am a bit jaded when I hear cries of, “No man is above the law!” While this states an important precept, it invites rather than decides a further question: What exactly is the law with respect to presidents whose constitutional role is unique? (For example, I do not hold that every official subject to impeachment must first be convicted in an impeachment trial before he or she can be indicted; I take that view only with respect to the president, and I believe the precedents bear me out on this despite the fact that the language of Article I makes no distinction.)

To be fair, however, in the unprecedented circumstances of this unusual hypothetical, Professor Tribe’s argument doesn’t ignore the unique role of the president, it emphasizes it. Moreover, to the ethical principle that “no man is above the law” may be added the important principle, enshrined also in the American constitutional ethos, that “no man should profit from his wrongdoing.”

Suppose, for example, that the constitutional rule that a sitting president cannot be indicted resulted in the estoppel of any criminal prosecutions of the president once he left office because the applicable statutes of limitation barred such prosecutions. Here, the unique status of the president—that he cannot be indicted prior to impeachment—might serve to protect him precisely because his crimes had made him president in the first place.

These observations suggest to me some common ground that perhaps Professor Tribe and other critics and I share. As they assert, my arguments do not require the conclusion that an otherwise amply merited criminal indictment should be scrapped or suspended altogether while the president serves out his term. Indeed, the fact that a sitting president would otherwise be criminally indictable, or the identification of a president as an unindicted co-conspirator, is highly relevant as to whether he should be impeached and, even if not, as to whether he should be reelected.

Both Professors Akhil Amar and Walter Dellinger—and Professor Tribe himself—have suggested that a sitting president might be indicted but not prosecuted. This seems to go a long way to meet my prudential concerns while responding to the ethical points made by critics of my views. It also suggests that some steps must be taken to toll the statutes of limitation that might otherwise preclude a prosecution after the president leaves office.

Certainly I ought to agree that where a presidential candidate has won office through a campaign that committed crimes in order to bring about his election, he should not be permitted to avoid exposure in the present and ultimately avoid prosecution in the future when he leaves office, by taking advantage of the fact that his crimes paid off and he currently enjoys the unique prerogatives of the presidency.

I believe that the Congress just sworn in should not begin its labors by focusing on an impeachment proceeding, and that commencing such an all-consuming preoccupation should await any report produced by the special counsel. Yet it may nevertheless serve our constitutional system well to have Congress close this loophole. The respected columnist Elizabeth Drew has recently written that, “An impeachment process against President Trump now seems inescapable. Unless the president resigns, the pressure by the public on the Democratic leaders to begin an impeachment process next year will only increase.”

Perhaps action on the statute-of-limitations loophole might serve to abate some of the pressure Drew identifies until the public knows more definitively if the president was in fact part of a conspiracy to pervert the course of a presidential election by acting in league with a hostile foreign power, or if he is guilty of making false statement to impede an investigation into this kind of conspiracy—including false statements to the public.

This might give Congress some breathing room to follow the wise counsel of the new speaker of the House: “It’s about the facts and the law, and where that takes you,” Nancy Pelosi said on Jan. 3. “We have to wait and see what happens with the Mueller report. We shouldn’t be impeaching for a political reason, and we shouldn’t avoid impeachment for a political reason.”

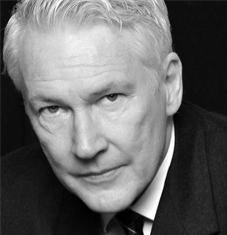

Philip Bobbitt is the Herbert Wechsler Professor of Federal Jurisprudence at Columbia Law School and with Charles L. Black, Jr. the author of “Impeachment: A Handbook” (Yale, 2018).