Is Internet Content Too Engaging?

Editor’s Note: This post is partially based on Curation as Competition, Curation as Vice, by Gerald Adams III and Jane Bambauer.

Social media companies are facing a new flavor of regulation. Across the country, lawmakers and litigators are attacking “addictive design” features like infinite scroll, autoplay videos, and algorithmic feeds. The theory is that these features are design defects under products liability laws.

In the last two years alone, the momentum has been building. Utah passed legislation allowing minors to sue platforms when “excessive use” of curated feeds harms their mental health. California requires companies to identify and reduce "addictive" elements in their products. A coalition of 41 state attorneys general and several school districts have sued Meta over algorithms they claim hurt young users. Even the former Surgeon General wanted warning labels on social media—just like cigarettes and alcohol.

What makes these approaches appealing to regulators is that they seem to dodge First Amendment concerns. By targeting design rather than content, they hope to regulate social media without constitutional roadblocks.

These product defect theories have three major problems. First, state statutes and product liability lawsuits based on the selective display of content may be foreclosed by Section 230 immunity.

Second, they probably run afoul of First Amendment protections. Home feed algorithms are a form of expression that should be protected for the users’ sake, if not the platform’s.

And third, these laws and lawsuits clash with the policy goal of increasing competition in the digital marketplace. The Biden administration pushed to break up “Big Tech” monopolies to create more consumer choice, and the second Trump administration is continuing this mission. But the very features that regulators now condemn as “addictive” are the primary ways that platforms can compete with each other. These conflicting regulatory agendas reveal an incoherence in the popular legal treatments of media platforms, and a misunderstanding of what it means to compete in the digital media economy.

Section 230

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act is the federal law that immunizes platforms from civil liability based on their decisions to host, distribute, or take down user-generated content. Many of the state laws that attempt to regulate social media algorithms will conflict with Section 230 because they create liability for platforms based on their decisions about which third-party content to amplify. Proponents of the laws, like the plaintiffs in the class action claims, believe that content promotion can be distinguished from the decision to host or remove content that receives Section 230 protection. For example, the complaint in Oakland Unified School District v. Meta argues that the claims Meta based on addictive algorithms are not covered by Section 230 because:

[The] Plaintiff is not alleging Defendants are liable for what third parties have said on Defendants’ platforms but, rather, for Defendants’ own conduct. As described above, Defendants affirmatively recommend and promote harmful content to youth, such as pro-anorexia and eating disorder content. Recommendation and promotion of damaging material is not a traditional editorial function and seeking to hold Defendants liable for these actions is not seeking to hold them liable as a publisher or speaker of third party-content.

This does not make a lot of sense under the policy goals of Section 230. The purpose of Section 230 is contested, but it’s usually expected to make sure legal risks won’t cause platforms to over- or under-moderate. First, recommendations do seem like a traditional editorial function (e.g. deciding which stories are “above the fold”) and the ability to upgrade some content and downgrade others is a pragmatic option that allows platforms to boost the posts that are most fitting and hide the posts that are boring or problematic without the harshness of content removals or user suspensions.

So far, most courts have treated amplification and home feeds as a part of the content moderation functions that are protected from suits by Section 230. Several states’ attorneys general and school districts filed claims against Meta that were dismissed if the claim was based on the “timing and clustering of notifications of third-party content in a way that promotes addiction” or based on the “use of algorithms to promote addictive engagement.” But some design defect and public nuisance cases have been allowed to proceed, so the issue is not entirely resolved. This opinion, preserving claims brought against Snapchat from a Section 230 dismissal, will get you up to speed on the statutory interpretation battles.

The First Amendment

Some laws and consumer protection strategies attempt to treat social media as products that are defectively designed. Design defect theories require showing that a good could have been designed in a way that would have been safer while still offering comparable utility and price. But speech is not a typical good, and the First Amendment is likely to provide protection to the producers of websites, content apps, and home feed algorithms. First of all, to the extent that courts understand social media to be analogous to traditional forms of media like books, cases like Winters v. Putnam & Sons, which held that book publishers could not be sued under products liability, seem to completely foreclose design defect theories. Courts may come to view the free speech interests of social media companies differently since they are intermediaries interposing their own decisions and software between the speakers and listeners, but the Supreme Court clearly signaled that social media companies have some First Amendment rights. In Moody v. Netchoice, the Court explained that laws regulating how platforms “organize” or “prioritize” content impede their right to editorial discretion. California’s Age-Appropriate Design Act has been enjoined as a result.

Proponents of social media product defect claims will find hope in Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s concurrence in Moody, where she questioned whether algorithms optimized for profit maximization should receive free speech protection. Sure enough, a federal district court in Florida recently latched onto Justice Barrett’s concurrence while declining to consider the First Amendment application to the AI-generated output of chatbots. But neither Justice Barrett nor the Florida opinion has fully grappled with the First Amendment interests of listeners. After all, social media users have strong, independent rights “to receive the information sought to be communicated.” Personalized content feeds serve listener interests—indeed they may be a necessity to fully realize listener rights in an information-saturated environment. Algorithms help users actively find or passively discover speech that they evidently want to consume from an unmanageable flood of content.

Some commenters recognize that product defect and consumer protection claims are likely to face at least intermediate scrutiny under the First Amendment, but they remain confident that government intervention can meet this test. After all, since the plaintiffs’ theory is that the infinite scroll and content-selection algorithms are addictive, the implication is that the listeners’ autonomy has been overridden, and that the free speech interests are therefore diminished.

I disagree. Courts applying intermediate scrutiny require the government to prove that social harms from speech are “real, not merely conjectural” and that restrictions "alleviate these harms in a direct and material way." The evidence linking social media to mental health problems doesn't clear this bar yet.

Researchers have raised serious concerns that social media and other content platforms hijack the brain, cause addiction, and interrupt social development. In addition to popular accounts of these problems, Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have compiled a library of published peer-reviewed research that presents a large and still-expanding list of possible harms: depression and anxiety, body objectification, compulsive use, and suicidality.

But the research on social media harms actually shows mixed results. A report by the American Psychological Association states that “using social media is not inherently beneficial or harmful to young people.” Meta's internal research that prompted concern about the effect of Instagram on teenage girls actually found that most users reported Instagram either had no impact or made things better. Even the Surgeon General's advisory acknowledges that “we do not yet have enough evidence” for definitive conclusions. While some studies show correlations between social media use and mental health issues, they often lack the research design features that can show that social media use causes mental health decline, and not the other way around.

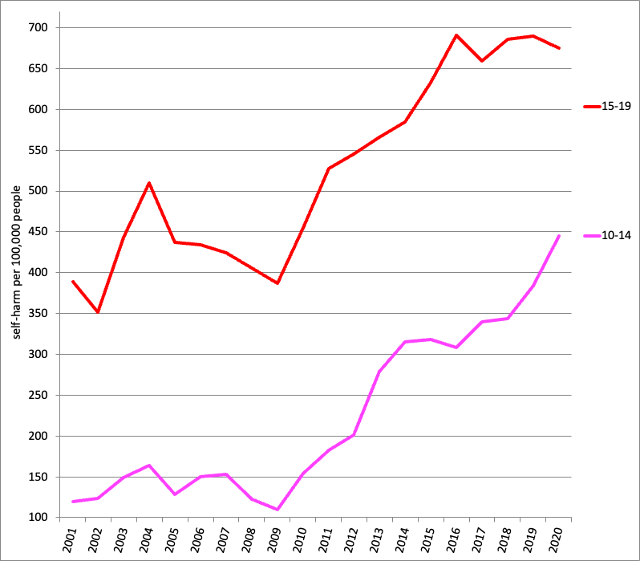

Consider, for example, the evidence that once seemed to me the most compelling. Jean Twenge presents this graph, showing the sharp increase in hospitalizations of female youths due to suicidal ideation, as evidence against the claim that the mental health crisis might be an illusion caused by better reporting:

Figure 1. Trend in U.S. emergency room admissions with a self-harm diagnosis

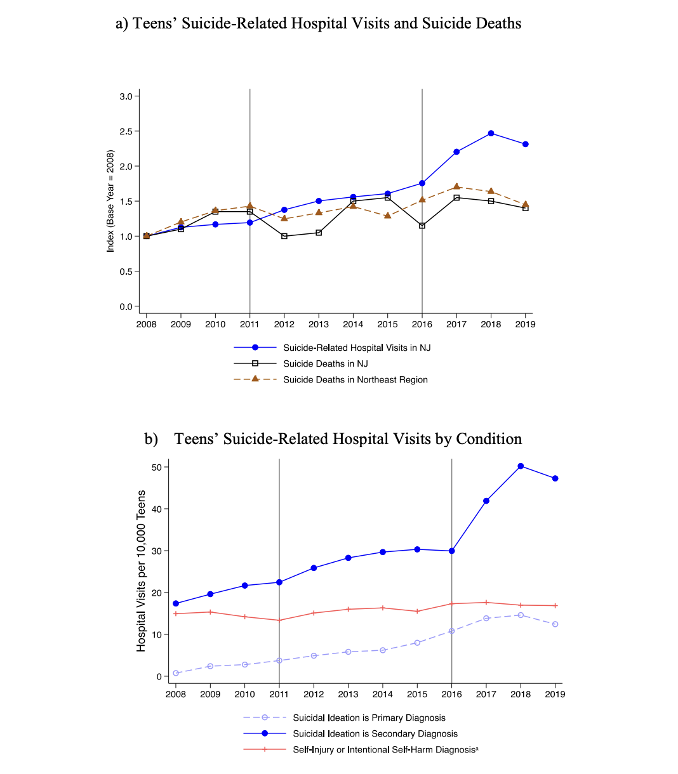

But even putting aside the fact that the trend line starts to spike well before social media had permeated teen culture, the graph may actually prove the skeptics’ point. Analyses of completed suicides and primary diagnoses of intentional self-harm have actually stayed pretty flat, while “suicidal ideation” as secondary diagnoses have risen.

Figure 2. Trend in New Jersey emergency room admissions with a self-harm diagnosis, broken into primary and secondary diagnoses and distinguishing ideation from self-harm action

If courts intend to stay consistent with past Supreme Court rulings, the level of addiction that would be required to overcome First Amendment freedoms would have to be quite compelling. After all, nude dancing, pornography, and fear-mongering propaganda are all protected forms of expression despite their success at siphoning attention away from higher-minded affairs. Perhaps the lawmakers and plaintiffs will have some success regulating social media’s distribution of certain types of harmful media (like pornography or pro-anorexia messages) to young social media users, but attempts to penalize products because they are too entertaining are likely to encounter the same challenges as the ordinance struck down in Schad v. Boroughof Mount Ephraigm that prohibited live entertainment.

When the Supreme Court struck down restrictions on violent video games in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, it reminded Americans that moral panics have accompanied nearly every new speech technology that captured the attention of young people. “Penny dreadful” novels, comic books, radio, television, and videogames have all taken their turn in the barrel as causes of social decline, but in hindsight, none seem to have caused the deleterious effects that were predicted when they were new.

We ought to stay skeptical, even when new technologies seem to be categorically different from what has come before, if the nature of the social risk is that an audience finds a form of expression too persuasive or too engaging. At some point, an AI-enabled technology may emerge that overpowers our cognitive independence (such that it is). Speech products, especially virtual reality, might become so engrossing and disorienting that they will be more similar to psychedelic drugs than movies and books. At that level of compromised self, I can imagine listener interests would diminish or fall away entirely. The line-drawing will be difficult at some point, but we should not fool ourselves into thinking that doom-scrolling is close.

Competition Policy

On top of the constitutional problems, proponents of “addictive design” theories misunderstand the impact that regulation and liability will have on media competition. In a world where content is abundant and attention is scarce, platforms that manage to reach a critical mass of users compete not just on size but also on curation quality. When users have countless options for information and entertainment, the platform that best matches each user to the right content at the right time provides a superior product. This curation function is what users value and what keeps them engaged.

TikTok provides a good example. TikTok didn't overtake established platforms like YouTube by having more users or more content; it succeeded by creating a better algorithm that more effectively curated content to individual preferences. Indeed, Meta proved that home feed algorithms are at the heart of competition: When they switched several thousand Facebook and Instagram users to reverse chronology feeds on an experimental basis, those users got bored, decreased their usage, and dramatically increased their usage of rivals TikTok and YouTube.

The engagement-maximizing features that regulators now condemn—personalized feeds, recommendation algorithms, infinite scroll—are the primary dimensions on which upstart platforms can compete. By finding the most engaging content for the users, the home feed algorithms are platforms’ best attempts to conserve users' most precious resource: their attention. The platform that shows users what they want to see in the most efficient way will win the competition for engagement. Generative AI will begin to compete in roughly the same way, anticipating in advance what type of content the user wants to be summoned or made up. If engagement is regulated away, today’s dominant social media and AI firms will be given the greatest gift a lawmaker could possibly bestow on them: a large, government-created moat.

So, Do We Want Competition?

This brings us to a jarring conclusion: Competition policy and consumer protection are not complementary goals in the platform economy—they're in direct conflict. For years, lawmakers have pursued these objectives simultaneously, assuming they reinforce each other. Tim Wu, who helped shape Biden's antitrust agenda, advocated breaking up “attention merchants” like Meta while simultaneously condemning the very means of competition (data collection) and the ends of competition (engagement maximization).

These contradictions reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of digital media markets. If platforms compete by curating content to maximize engagement, then regulations targeting these features aren't just restricting speech—they're undermining competition itself. Unlike traditional vice industries where age limits or warning labels create only marginal limits on competition, rules against “addictive design” strike at the core of how platforms differentiate themselves. Lawmakers need to confront an uncomfortable truth: In digital media, the cure for one perceived problem may be the disease for another.

-(1).jpg?sfvrsn=a0f57148_5)