Misinformation Studies Meets the Raw Milk Renaissance

A review of National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science” (The National Academies Press, 2025).

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s recent report, “Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science,” landed at an awkward moment: Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a longtime anti-vaccine crank, was going through Senate confirmation hearings to become the secretary of health and human services. The report is written by a deep bench of experts who genuinely understand both the challenge and the stakes. National Academies reports have sought to provide “independent, objective analysis” to address complex problems and inform public policy decisions since 1863. Misinformation about science is one such problem, as challenges ranging from COVID-19 to climate change have made clear.

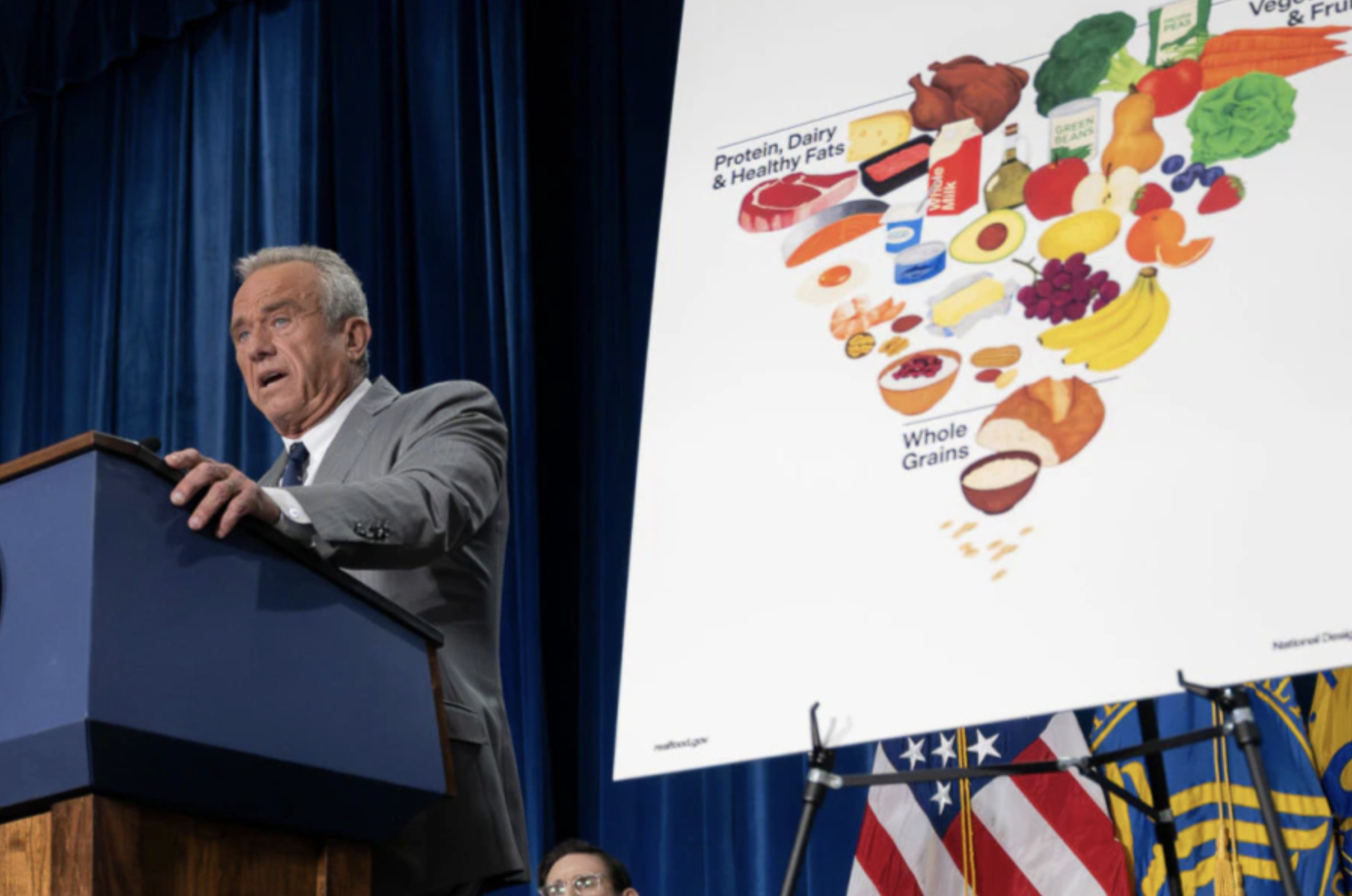

By the time my print copy arrived, Kennedy had been confirmed, the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement had the wheel, and misinformation about science was liberally flowing with the official imprimatur of the U.S. government. Except those producing the false and misleading information called it something else: “Gold standard science.”

The secretary of health and human services released a “MAHA report” on children’s health with AI-hallucinated citations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) rewrote its vaccine safety web page (at Kennedy’s insistence) to imply that vaccines might cause autism. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, whose members had been replaced by anti-vaccine loyalists friendly with Kennedy, chipped away at the childhood vaccine schedule—voting to stop recommending the hepatitis B vaccine at birth and dropping the combined mumps, measles, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine—before a Health and Human Services directive simply bypassed the committee entirely, issuing a directive that moved yet more vaccines out of universal recommendations. Health and Human Services canceled grants to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) because AAP is “woke” and critical of the secretary. Senior officials who refused to play along with all of this were fired or pushed out.

None of these shifts reflected a change in the underlying scientific evidence. They reflected the change in who controls the machinery of the state, including the official channels through which science is communicated. Other scientific bodies have pushed back—the World Health Organization’s Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, for example, responded by releasing a new review of 31 studies published since 2010 showing once again that there is no evidence of a causal link between vaccines and autism—but prominent MAHA, wellness, and right-wing political influencers had already begun touting the CDC’s new language as vindication of their beliefs.

How should we think about what we’re dealing with here—and what lessons can be gleaned from a comprehensive and authoritative National Academies report that was written before this power shift occurred?

The National Academies Report

The National Academies report begins by wading into the definitional wars over the word “misinformation”—a contested term both politicized by those who find facts inconvenient and, at times, overused by academics and political elites to dismiss statements of opinion. “Misinformation about science,” the report says, “is information that asserts or implies claims inconsistent with the weight of accepted scientific evidence at the time.” Disinformation is a subset, spread by actors who know it is false.

Rather than treating misinformation as a failure of individual cognition, the report emphasizes that it is a systems problem. Misinformation about science arises from and circulates through interactions among individuals, communities, institutions, and media. It is exacerbated by social media platform design, by economic incentives that reward speed and sensationalism, and by long-standing inequalities in access to high-quality information. It can originate with corporations, governments, advocacy groups, alternative health media, mainstream journalists, university press offices, or ordinary users. It is especially potent when it comes from sources considered authoritative by many, or when it is amplified by powerful actors.

On the question of the impact of misinformation, the report is appropriately cautious: It notes that there is strong evidence that exposure to misinformation about science produces misbeliefs. People who encounter it may come to hold false beliefs about vaccines, climate, or reproductive health. Yet the report also acknowledges that it is much harder to draw clean causal arrows from those beliefs to subsequent behavior. Most studies of misinformation about science are short term, focused on self-reported intention rather than observed action, and topics skew heavily toward COVID-19 and vaccination. The committee emphasizes what we can say—misinformation contributes to misbeliefs and probably to some harmful choices—without implying that every anti-vaccine meme can be directly linked to a specific action.

And yet, the report notes, the harm is not necessarily distributed evenly. The report foregrounds the idea of “communication inequalities”: Communities that are already disadvantaged often have less access to accurate, culturally relevant, translated science information and more exposure to lower-quality, less scientifically accurate content. On social media, content moderation efforts (which, since the report was released, have declined significantly!) are heavily English-centric. Misinformation about science is a universal vulnerability, but its harms fall hardest on those who already have worse health outcomes and good historical reasons to distrust institutions.

So what are we to do about it?

On remedies, the report methodically walks through the evidence for a menu of individual-level interventions—prebunking, debunking, accuracy prompts, nudges that prompt “evaluative thinking,” reminders to read before sharing, lateral reading tips—that can, in controlled settings, reduce belief in or sharing of misinformation about science. It concludes, correctly, that these interventions (often grouped under the umbrella term “media literacy”) show some promise but tend to have modest effects that weaken over time, and that almost all the evidence comes from experiments that are hard to scale in the wild. The report points to more structural levers of change as well—support for newsrooms, platform transparency, emergency communication capacity in public agencies, legal and regulatory tools—but here the evidence concerning effects is thinner, because almost no one funds careful evaluation of those interventions.

One of the report’s most important sections—frequently underemphasized in the solutions conversation—is the discussion of community-based organizations (CBOs). The committee repeatedly returns to CBOs, including local businesses, faith groups, and media, as “particularly well positioned” to identify information needs in their communities and fill local science information voids. It urges funders and professional societies to invest in these actors and even suggests building an independent consortium to curate and periodically review high-quality science information, with equity and access as central design goals.

As a synthesis of the literature on misinformation about science, the report is admirably clear and careful. It gives policymakers, funders, and researchers a shared vocabulary and a systems map. The authors should be commended for wrangling a significant project and making a complex topic comprehensible.

But the report is calibrated for a world in which institutions such as the CDC and Health and Human Services are mostly part of the solution. We’re in the raw milk renaissance now, and those institutions have been retooled to broadcast anti-science narratives.

Indeed, by the definition the National Academies report offers, the U.S. government itself has become a prominent purveyor of “misinformation about science.”

Where “Misinformation” Falls Short

That recognition makes the report’s framing of “misinformation” feel a bit thin. As a descriptive label for individual “claims inconsistent with the weight of the evidence,” it’s fine. It is useful for coding studies, situating research, and writing grant proposals. (Well, not since January 2026; National Institutes of Health Director Jay Bhattacharya, who postures as an anti-censorship crusader on podcasts, has overseen procedures to screen grants for forbidden terms and canceled grants related to countering misinformation.) But the term flattens the politics out of what MAHA actually is: not just a collection of false claims, but a project that activates and recruits around them—a health-populist movement with the explicit aim of capturing the institutions that define what counts as science and putting its beliefs into practice through policy.

I’ve studied the anti-vaccine movement for over a decade—and organized against it (and RFK Jr.) in California in 2015, helping galvanize support for a legislative effort to strengthen public school vaccine requirements as a pro-vaccine mom. That experience left me convinced that a narrow focus on misinformation and factual claims misses what’s actually driving the movement: deep currents of identity and belonging, distrust of institutions, and the appeal of a story that names villains and offers community. You don’t solve that with better fact sheets.

MAHA has long told a story about a chronic disease “epidemic” caused by corrupt elites, pharmaceutical products, processed food, and vaccines. It blends some real grievances—ultraprocessed food, environmental degradation, legitimate anger at real misconduct by drug companies—with discredited claims about vaccines causing autism, SSRI antidepressants as a conspiratorial plot, and so on. Now, from its foothold in the administration and perch at the helm at Health and Human Services, MAHA launders misinformation through the federal brand. The National Academies report gestures at “competing interests,” “public relations,” and “societal forces” as well as wellness influencers and fringe groups corrupting the information environment, but it does not fully conceptualize health populism as a political project with the explicit aim of redefining what “science” the state will endorse. “Misinformation” is the mobilizing content, not the end state; the false claims help build the army, but outside voices are delegitimized. What MAHA produces, what Children’s Health Defense and the anti-vaccine movement’s influencers and media have long produced, is propaganda: narratives designed to galvanize belief, build identity, and legitimate a political project. The term “misinformation” treats this as a knowledge problem. It’s a power problem.

The report is very cautious when it comes to tackling power politics. It acknowledges governments, corporations, and platforms as potential sources of misinformation, but mostly as if they are just additional accounts in the feed. It does not spend much time on jawboning—politicians leaning on platforms or agencies to change enforcement practices, or to delegitimize the very idea of fact-checking, or facts. It does not spend much time addressing the issue of misinformation about scientists—the types of delegitimization and smear campaigns that climate scientists, vaccine researchers, and others have endured. Creating misinformation about an expert, it turns out, is an effective way to delegitimize their publications and public statements. Disinformation campaigns that incorporate decontextualized FOIAed documents, for example, are used to flood channels with “receipts,” and the resulting pseudo-scandals are leveraged to justify gutting research programs. One of the most significant failures of the past five years has been how slow academic and scientific institutions were to fully internalize just how serious the fracturing of reality and attacks on their legitimacy actually were. They brought fact-checks to a political knife fight, not recognizing that their opponents were serious, coordinated, and often far better at communicating in the present information environment than were their targets.

The National Academies report rightly insists that we have to move beyond methodological individualism. It catalogs communities, institutions, and structural conditions in the information ecosystem as the layers where misinformation about science is both produced and felt. But when it turns to prescriptions, the report slides back toward the familiar: teach individuals to think better, train journalists, write better fact sheets, ask platforms nicely to tweak their designs. The truly structural options—redesigning social media platform incentives, re-architecting information flows—are noted but not developed. That is not the authors’ fault; the literature they are synthesizing is overwhelmingly individual-level. But it does mean that the “systems” rhetoric can feel more like a vibe than a concrete blueprint.

CBOs as Infrastructure, Not Garnish

One of the report’s most promising suggestions, and the one that becomes most important in our networked future, is its emphasis on community-based organizations. In the committee’s report, CBOs, local businesses, faith institutions, and local newsrooms are “particularly well positioned” to identify information needs and fill science information voids because they have durable relationships and trust. In the world the report was written in, these actors were imagined to be helpful complements to federal agencies.

In the world we inhabit today, they are infrastructure for resilience.

Evidence-based influencers and collectives have begun to emerge, building networks to communicate quality information where the majority of people actually spend their time. Some scientist-activist and doctor-influencer types have very effectively leveraged the demonstrably resonant communication styles used by their opposition: Doctor Mike, Your Local Epidemiologist, Michael Mann, to name just a few. Public health officials in a handful of states have begun to form alliances to communicate independently of federal institutional authorities. Public-private partnerships have explored multi-stakeholder collaboration to enable rapid response to viral rumors. These approaches, often understudied by the Academies, are creating what the report is looking for. Funders: This is where we should be experimenting.

Overall, as a synthesis, the National Academies report is rigorous and admirably transparent about what we know and what we don’t. It provides a shared vocabulary and systems map. It highlights the need to focus on community-level and systems-level interventions and calls out the limitations of our current, individually focused evidence base. For agencies, funders, and researchers trying to make sense of an unruly literature, and for readers interested in a deep dive into what we know and don’t know about misinformation about science, it is a valuable document—but one that should be read with an understanding of the connection between what it does not say, and how we got to where we are today.