One County, 650 Migrant Deaths: An Introduction

The sheriff of a rural Texas county granted me access to the death reports of hundreds of people who passed away trekking through his jurisdiction to avoid a Border Patrol checkpoint. Here is their story.

The office of Brooks County Sheriff Urbino “Benny” Martinez’s has a quintessentially South Texas feel. Its wood-paneled walls are adorned with awards, a mounted shotgun and a wooden Texas flag.

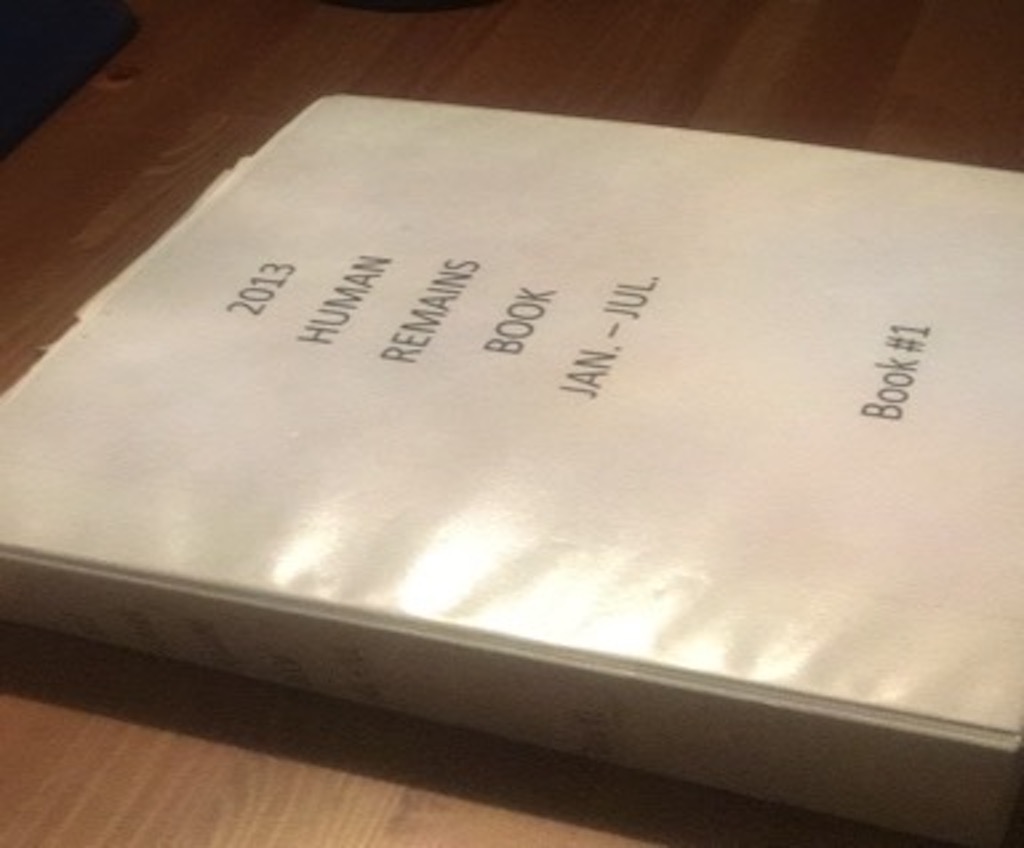

But when I sat down with Sheriff Martinez for the first time a year ago, my attention focused not on the decor but on a white three-ring binder sitting on the sheriff’s desk. The binder was nondescript, but it had a striking label: “Human Remains 2018.”

I had come to Brooks County to learn more about the hundreds of people who die traveling into the United States as they attempt to circumvent the nearby Customs and Border Protection (CBP) checkpoint that polices traffic moving north through this part of Texas. Combined with changing U.S. immigration and border policies, this checkpoint has turned the surrounding ranches into ground zero of a constant humanitarian crisis. For people trying to enter the interior of the United States without immigration papers, there are only two options to successfully move north: try to pass through the checkpoint undetected or hike around it through the dense Texas brush.

Those who choose the latter option risk never making it out alive.

Brooks County is the deadliest county in Texas for migrants trying to enter the United States—and it isn’t even directly along the border. Over the past few years, while American policy focus has lasered in on asylum-seeking Central American families and unaccompanied minors, there is another migration pattern 70 miles north of the border. Here in Brooks County, groups of almost exclusively adult migrants hike remote trails and look to evade the Border Patrol in their bid to enter the United States. Some are caught, and some make it through the county undetected. But at least 650 people have passed away on this Texas ranchland since 2009, only a few hours south of San Antonio and Austin. Each time a body is discovered on a ranch in Brooks County, a death report ends up in Benny Martinez’s office in a white three-ring binder like the one I saw on his desk in August 2018.

Sheriff Martinez and his team are among the first responders called to any discovered bodies in Brooks County. They drive out to the location, photograph and document the scene, and then write up accounts of what they found. These written descriptions contain GPS coordinates of the bodies and the discovering party, along with the body’s belongings, clothing and any identification.

The white binder I saw sitting on the sheriff’s desk held 34 of these files for 2018 (from January through early August). Each file represents a life cut short; each page hints at a story much bigger than just the journey of migration.

As I flipped through the pages, I stopped at a picture of a young woman who had been discovered on March 20, 2018. It wasn’t the kind of image I had expected to find in the binder. The woman wore a black tank top and black sweatpants, and carried a red case containing glasses and makeup. Tucked in the case was also a list of phone numbers written on a white sheet of paper in alphabetical order, with the top number listed as “Abuelita”—a term of endearment for grandmother. According to the Mexican ID card that she had carried with her, she was 28 years old at the time of her death. We were the same age, our birthdays separated by exactly 10 days.

It wouldn’t be the first time I’d have my assumptions challenged by the contents of the 2018 Human Remains binder. Indeed, I was wholly unprepared for what it contained, and the same was true of the similar binders stashed in a filing cabinet in a nearby room, one for each year starting in 2009. I hadn’t expected to see so many women in the case files—certainly not women who carried lipgloss, beaded bracelets and fanny packs. I hadn’t expected to see so many older crossers in their late 50s and 60s, people who were found with reading glasses and who had children and grandchildren already in the United States. I was not expecting so many people who had died trying to get back to families left in the United States.

I also hadn’t expected to be reading love letters, deportation papers and hospital notes found in pockets; looking at wedding rings on left hands and pictures of smiling partners and children tucked into wallets; or analyzing some of the more curious sentimental items that people carried with them, including a bag of pebbles and seashells, two signed baseballs, and a stuffed animal in the shape of a horse. Yet such details—and so many others—filled every page.

During a subsequent visit to Brooks County and Sheriff Martinez’s office in January of this year, I sat once again across the desk from the now fuller 2018 Human Remains binder. Since my previous trip, the total number of case files for the 2018 binder had reached 50. During the previous months, I had thought more about the files stored in those white binders, and I now asked Sheriff Martinez if I could put the files into a database to look for demographic trends. I didn’t expect him to grant me access. But it turned out not to require a hard sell. He agreed to share with me all the binders—and the reports they contain—with only one condition: that I make recommendations for ways to improve his team’s search and rescue and body recovery efforts.

It was a deal.

At the time, I didn’t realize how uncommon an agreement we had forged. This became clear only months later, when I began reaching out to other South Texas counties and realized how few offices even keep these types of files. Too often, these reports are mixed in with other incident reports, with no effort to track trends or numbers. Equally uncommon was the openness of the entire Brooks County Sheriff’s Office. Starting at the top with Sheriff Martinez, the office staff and law enforcement officers didn’t just tolerate the project; they championed it.

With this support, I began documenting each case file, along with my colleague Ellie Ezzell. Sheriff Martinez offered up his desk as our official work space, and we spread the binders across the light-colored wood and got to work. We built a database with 58 variables to capture each case file’s details. We based our inputs on the written descriptions and available death certificates, scouring the photographs for signs of other belongings left out of the case files.

The details of each case are unrelenting in their humanity and tragedy. Each file and each person’s story is an entire world, and the pages reflect everything from determination, to family unity, to violence, to love. In the aggregate, these cases also offer a frontline look into one of the hidden corners of Mexican and Central American migration over the past 10 years. It’s a look both into the human toll of inaccessible legal immigration pathways and current U.S. enforcement strategy that push people into ever more remote areas, and into the people who are making the journey anyway.

The pages also provide a glimpse into how these policies have affected the 7,200 residents of Brooks County. One file notes how a ranch owner discovered a body while putting out hay for her animals. Another rancher found a skull after stepping out onto his porch in the early morning with a cup of coffee and noticing his dog chewing on something, while yet another found a human skull out in his fields while looking for a missing calf. These details highlight how the daily lives of Brooks County residents butt up against immigration and border policies designed in rooms far away from their own.

These 650 cases in the Brooks County Sheriff’s binders tell a story about the men, women and minors who have crossed into Brooks County over the past decade. In the series that follows, I’ll examine their journeys, their lives and the loved ones they left behind. I’ll explore both the larger trends and individual cases, with the hope of shining light on the collective narrative of the people whose lives have ended in Brooks County and the continuing tragedy of immigration through South Texas. I’ll also examine what could be done to make Brooks County less deadly, and what is happening in other nearby counties where migrants are also dying.

But to tell the story of what is going on in Brooks County and who has died on this land, we have to begin at the Falfurrias CBP checkpoint. This lone piece of infrastructure is the powerful, quiet force that sets in motion these 650 cases, rerouting thousands of people traveling north off the highways South Texas and into private ranchland.