On the Special Counsel’s Weird Prosecution of Michael Sussmann

The indictment of Michael Sussmann is far removed from the supposedly grave FBI misconduct Durham was supposed to reveal. It’s also a remarkably weak case.

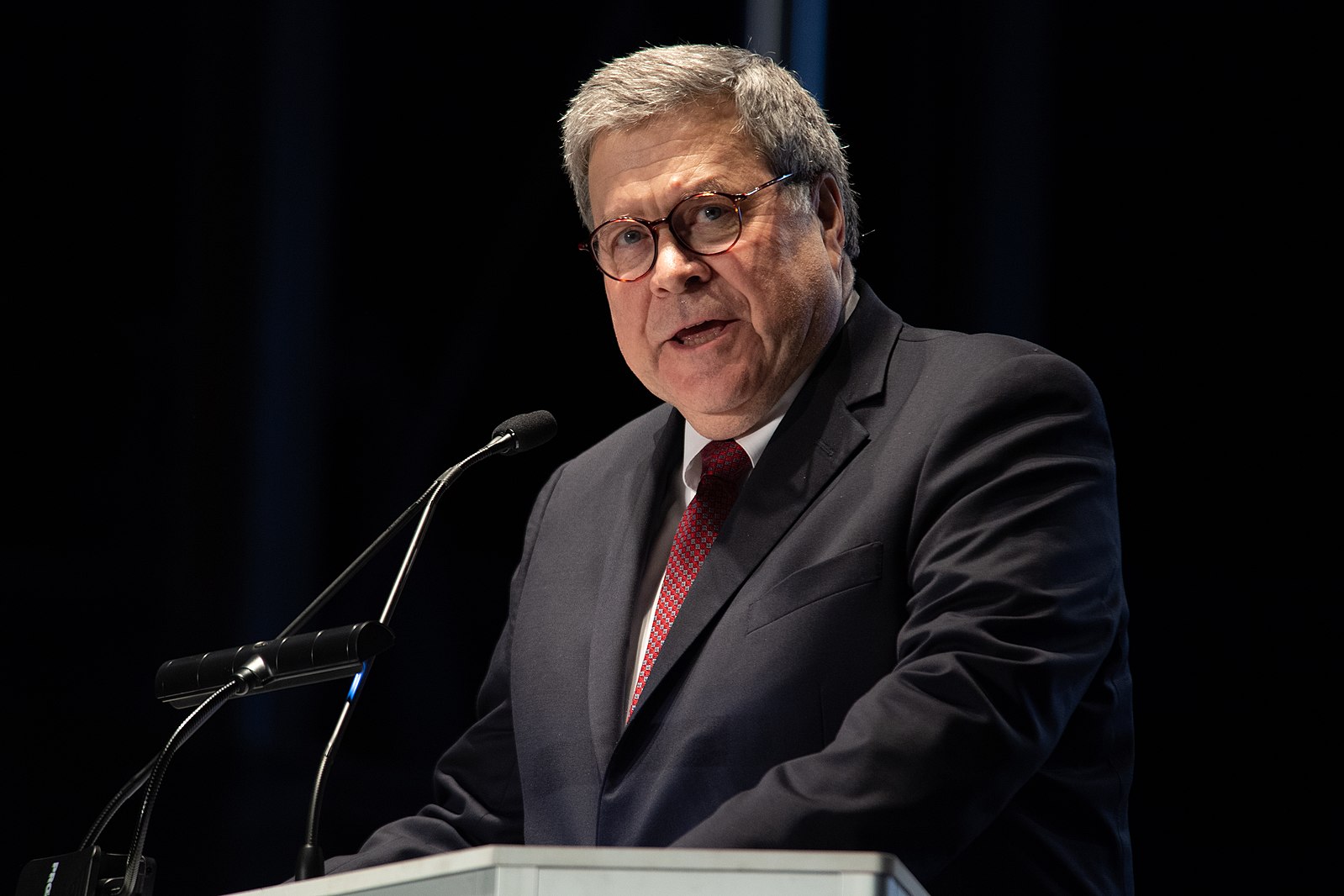

Attorney General William Barr appointed John Durham, lo these increasingly-many years ago, to investigate a supposed scandal inside the FBI: There had been an attempted coup, President Trump alleged, and Barr himself hinted that there had been an effort spuriously to investigate a candidate for president. The FBI counterintelligence investigation of figures surrounding Donald Trump, the attorney general warned darkly, may have begun earlier than the FBI said it did. It may not have been properly predicated. There may have been other agencies involved.

Durham himself at times lent his solid reputation as a career prosecutor to such fantasies. When the Justice Department’s inspector general found that the investigation of L’Affaire Russe had been properly predicated and had, in fact, begun when the FBI always said it had, Durham publicly questioned the judgment. He also has taken a mind-bogglingly long time to complete his as-yet almost-wholly unproductive investigation, which has gone on longer than the Mueller investigation itself, building up expectations among many Trump supporters that Durham was going to deliver the goods.

And until this week, Durham’s investigation had added exactly zero new facts to the public’s understanding of the FBI’s handling of the Russia matters. The only case he had brought—against a low-level FBI lawyer for altering a document in connection with a surveillance application—was entirely derivative of facts developed by the inspector general. Durham had, beyond that one case, issued no findings or reports and had charged nobody with anything. He had merely existed and, by existing, allowed expectations and conspiracy theories to swirl around him.

But now Durham has spoken on his own. He has indicted a cybersecurity lawyer named Michael Sussmann for allegedly making a single false statement in a conversation in 2016 with then-FBI General Counsel Jim Baker. The allegedly false statement concerned not Trump or Russia, but whom Sussmann represented when he brought Baker some information about an alleged electronic connection between the Trump Organization and a Russian bank. (Disclosure: Baker is a personal friend and former colleague at Brookings and Lawfare.)

The indictment is, in other words, far removed from the grave FBI misconduct Durham was supposed to reveal. Very far removed. In fact, it doesn’t describe FBI malfeasance against Trump at all, but portrays the FBI as the victim of agitprop brought to it by outside political operatives. It describes the FBI as diligently running down the leads it had been fed by these operatives and then, well, dropping the matter when it learned they had no merit. The misconduct it portrays is an alleged lie by Sussmann that is, at best, wholly peripheral to the substance of the allegations Durham was supposedly peddling.

Even taken on its own terms, the document is one of the very weakest federal criminal indictments I have ever seen in more than 25 years covering federal investigations and prosecutions. It depends in its entirety on the testimony of a single witness who is on the record, under oath, saying something rather different from what the indictment alleges. The indictment itself, as I’ll explain, also contains a number of facts that tend to undercut its central allegation.

So what is going on here? I believe that the indictment of Michael Sussmann is an effort by Durham to change the subject. Over at National Review, Andrew McCarthy speculates—very likely correctly, in my view—that:

Here is where the prosecutor appears to be going: The Trump-Russia collusion narrative was essentially a fabrication of the Clinton campaign that was peddled to the FBI (among other government agencies) and to the media by agents of the Clinton campaign—particularly, its lawyers at Perkins Coie—who concealed the fact that they were quite intentionally working on the campaign’s behalf, and that they did not actually believe there was much, if anything, to the collusion narrative.

There are a lot of reasons to be skeptical of this effort, which I’ll explain below. But the best way to understand the Sussmann indictment is as pressure on the defendant to help Durham develop this alternative history of the skullduggery of the 2016 campaign, either in his still in-progress report or—as I suspect—in prosecutions of some of the people involved for allegedly defrauding the United States.

Merci, No Coup

Durham was first appointed back in May 2019, not as a special counsel but to conduct what Barr termed a “preliminary review into certain matters related to the 2016 presidential election campaigns.”

“Certain matters” was a coy reference to Barr’s publicly expressed concerns that the FBI had been “spying on a presidential campaign.” The Durham investigation was concerned, at least early on, with what Barr had termed in congressional testimony “the genesis and the conduct of intelligence activities directed at the Trump campaign during 2016.” And Durham himself stated publicly that he doubted the FBI’s claim that the Russia investigation had begun when George Papadopoulos blabbed to an Australian diplomat in London that the Russians had “dirt” on Hillary Clinton in the form of “thousands of emails.” When the Justice Department’s inspector general found the FBI’s account of the origins of the investigation to be true and to properly predicate a counterintelligence investigation, Durham took the extraordinary step of issuing a press release declaring with his investigation ongoing that his “investigation has included developing information from other persons and entities, both in the U.S. and outside of the U.S. Based on the evidence collected to date, and while our investigation is ongoing, last month we advised the Inspector General that we do not agree with some of the report’s conclusions as to predication and how the FBI case was opened.”

It was no wonder that many on the Trumpist right, including Trump himself, looked to Durham to prove the widespread belief that the FBI had been engaged not merely in a complex investigation that included errors and screw-ups but in a corrupt effort to intervene in the political system and delegitimize a candidate for president.

Yet the indictment Durham issued this week against Sussmann suggests not a whiff of improper spying on Trump or his coterie by the FBI. Indeed, it suggests not a whiff of misconduct on the FBI’s part in any respect—though Durham still appears to have his eyes on certain matters within the bureau separately. The FBI, rather, is the supposed victim of Sussman’s alleged crime. Durham is contending that Sussmann—acting as a lawyer for the Hillary Clinton campaign and an unnamed technology executive—lied to the FBI about whom he was representing in the course of an elaborate scheme to get the FBI interested in a false story tying Trump to Russia.

A Speaking-in-Tongues Indictment

The indictment is crafted as a kind of “speaking indictment”—a charging instrument that prosecutors use to tell a larger story to the public. Yet the Sussmann indictment is speaking in tongues. It’s not just that the story it’s telling is not the story of a coup or of FBI malfeasance. It’s that the story doesn’t make a great deal of sense on its own terms.

The body of the indictment has little to do with Sussman’s supposed lie. It is telling the story behind the Alfa Bank server saga—a dead-end thread you might recall from the larger Trump-Russia story—and the efforts by people associated with the Clinton campaign to get it in front of the FBI.

The Alfa Bank story was never a big part of L’Affaire Russe. Yes, there was a flurry of press investigation of it in the month before the election, but major press outlets treated it cautiously, as the gravamen of the allegations—that there was some secret link between Trump and Russia through a Russian—couldn’t be substantiated. Lawfare, for its part, wrote almost nothing about the matter as part of our extensive coverage of Trump-Russia ties. The reason, quite simply, was that the allegations never made a great deal of sense. For those who need a refresher, the basic issue was that some computer researchers noted what the Senate Intelligence Committee later described as “unusual internet activity connecting two servers registered to Alfa Bank, a Russian financial institution, with an email domain associated with the Trump Organization.” The researchers’ hypothesis was that this activity might suggest a secret line of communication between the bank and Trumpworld.

It didn’t, as the FBI later discerned. The whole thing had an innocuous explanation. As the inspector general put it, “The FBI investigated whether there were cyber links between the Trump Organization and Alfa Bank, but had concluded by early February 2017 that there were no such links.”

But the machinations that the Clinton campaign, its lawyers, and a group of unnamed computer security researchers and executives went through to get the matter in front of the FBI and media occupies pages and pages of Durham’s 27-page indictment.

This story is, indeed, a sleazy one, in which a group of private investigators, computer security researchers, tech executives and Clinton campaign lawyers access nonpublic data to try to make a colorable case that the Alfa Bank connection represented something nefarious. They put together some white papers on the subject, displaying a pretty casual relationship with the truth along the way, and they dangled those documents in front of the press and law enforcement. It’s not a pretty picture, but it’s pretty typical of opposition research efforts in high-stakes campaigns. The sleaziness and lack of regard for truth is a good reason to be skeptical and careful about such efforts when they inevitably emerge in public during a campaign, but it’s not especially surprising either. It’s also a good reason for the FBI to vet carefully allegations that show up at its door, rather than immediately accept them as true.

What’s more, all of this material, which constitutes the majority of the indictment, is wholly non-germane to Sussman’s alleged lie. Sussman, after all, is not accused of lying about the substance of the Alfa Bank allegations, the manner in which the information was obtained or researched, or the role he played in preparing any of it. He is accused of lying about only one thing: who his clients were when he approached the FBI with the material in September 2017.

In other words, not only has Durham gone from investigating whether the FBI ran a secret spying operation against the Trump campaign to alleging that it was the victim of crime, but he has used this indictment to tell a mostly-unrelated tale about opposition research by the Clinton campaign and its supporters and lawyers.

The story, however, gets weirder.

Why Does This Lie Matter?

As best as I can tell, little if anything actually turns on the lie Sussmann allegedly told. Durham contends that Sussmann claimed in a meeting with FBI General Counsel Jim Baker that he was “not acting on behalf of any client, which led the FBI General Counsel to understand that Sussmann was convening the allegations as a good citizen and not as an advocate for any client.”

In fact, Durham alleges, Sussmann was representing two clients: the Clinton campaign and a tech executive who was working with the campaign to develop the allegations.

How, you might ask, might Sussmann’s fibbing about the identity of his clients affect anything?

Consider that if Hillary Clinton stood beneath a “Stronger Together” banner and given a press conference announcing the contents of the material that Sussmann delivered, and if Sussmann had then transmitted that material to the FBI on Hillary Clinton campaign letterhead, the FBI still would have had to investigate the matter—the FBI having no more policy against accepting information from political campaigns than from drug dealers, mob bosses and terrorists. It still would have run down the lead, and it still would have found the Alfa Bank allegations to be without merit—just as it did, in fact.

Durham struggles in the text of the indictment itself to explain why Sussman’s lie mattered—which is important in a false statement case because the false statement’s materiality is an element of the offense. (18 U.S.C. § 1001 makes it a crime to “knowingly and willfully ... make[] any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation” in “any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States.”) The question is of sufficient concern to Durham that he seeks to address materiality right up front and at some length—in paragraphs 5-6 of the indictment:

5. SUSSMANN’s lie was material because, among other reasons, SUSSMANN’s false statement misled the FBI General Counsel and other FBI personnel concerning the political nature of his work and deprived the FBI of information that might have permitted it more fully to assess and uncover the origins of the relevant data and technical analysis, including the identities and motivations of SUSSMANN’s clients.

6. Had the FBI uncovered the origins of the relevant data and analysis and as alleged below, it might have learned, among other things that (i) in compiling and analyzing the Russian Bank-1 allegations, Tech Executive-1 had exploited his access to non-public data at multiple Internet companies to conduct opposition research concerning Trump; (ii) in furtherance of these efforts, Tech Executive-1 had enlisted, and was continuing to enlist, the assistance of researchers at a U.S.-based university who were receiving and analyzing Internet data in connection with a pending federal government cybersecurity research contract; and (iii) SUSSMAN, Tech Executive-1, and Law Firm-1 had coordinated, and were continuing to coordinate, with representatives and agents of the Clinton Campaign with regard to the data and written materials that Sussmann gave to the FBI and the media.

The standard of materiality in the D.C. Circuit is a forgiving one for prosecutors: “The test of materiality is whether the statement has a natural tendency to influence, or was capable of influencing, the decision of the tribunal in making a [particular] determination. Proof of actual reliance on the statement is not required; the Government need only make a reasonable showing of its potential effects.” Still, it is not at all clear to me that a jury will find any of Durham’s claims about what the FBI “might have learned” to be persuasive evidence of materiality.

Indeed, Durham’s very next sentence, the one that opens paragraph 7, undermines the notion that Sussmann’s alleged lie mattered. It reads: “The FBI’s investigation of these allegations nevertheless concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the allegations of a secret communications channel with [Alfa Bank].” Durham does not allege that it took the FBI longer to reach this conclusion as a result of Sussmann’s alleged statement about his clients. Nor does he suggest that the bureau devoted excessive energy to the matter because it had been misled as to the apolitical nature of the source. The FBI, rather, received a lead; it ran it down; it dismissed it—just as it would have had the Alfa Bank material shown up wearing Hillary Clinton’s trademark pants suit.

The Evidence Is Weak

But there are deeper problems with the Sussmann indictment. The most important is that the evidence that Sussmann lied at all is weak.

As a preliminary matter, the indictment by its terms concedes that the entire case—notwithstanding its many pages of narrative of the conduct of the Clinton campaign and its agents—hinges on the testimony of a single witness: the former FBI general counsel, Jim Baker. This concession appears on page 18 of the indictment, which describes the Sept. 19, 2016, meeting between Sussmann and Baker at FBI Headquarters where the supposed lie happened. The indictment notably includes the fact that “[n]o one else attended the meeting.”

The result is that the case against Sussmann, for all the pages of detail regarding the development of the Alfa Bank story, is strikingly thin. It consists of only three components:

- First, Baker presumably testified before the grand jury and can be expected to testify at trial that Sussmann told him he was not acting on behalf of any client.

- Second, the contemporaneous notes of Bill Priestap, then the assistant director of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division, appear to corroborate Baker’s memory. “Immediately after the aforementioned ... meeting,” prosecutors write, “the FBI General Counsel spoke with the Assistant Director of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division. During their conversation, the FBI General Counsel conveyed the substance of his meeting with Sussmann. The Assistant Director took contemporaneous handwritten notes which reflect, in substance, the above-referenced statements by SUSSMANN and state in relevant part: ‘Michael Sussman[n] — Atty: [Law Firm-1] — said not doing this for any client’” (emphasis in original).

- Third, Sussmann’s statement to Baker is further corroborated by the fact that he allegedly made the same misrepresentation to another government agency in efforts after the election to peddle the story to that agency. While prosecutors cannot prove that Sussmann lied in September by proving that he later lied in January, the latter incident might be used to show that Sussmann had a pattern and practice of misrepresenting his client interests on this matter.

If this all sounds like thin gruel, the gruel gets a lot thinner when one looks at each of these pieces of evidence in any detail.

Start with Baker, on whose testimony the whole case will ultimately ride. We don’t know what precisely he told the grand jury that gives Durham confidence he can prove his case against Sussmann beyond a reasonable doubt. But we can infer that Baker must be the prosecution’s chief witness, and that his testimony must have implicated Sussmann. There simply is no other way to make a case about a single meeting with only two people present.

Moreover, we do know what Baker told a congressional investigation in a sworn deposition in October 2018. That deposition will give defense lawyers a great deal to work with in responding to the charges against Sussmann.

In that deposition, Baker makes clear that he had a “personal relationship” with Sussmann, on the basis of which he took a meeting with him and accepted the information, about which he was “quite concerned” and which he immediately gave to investigators.

The problem for Durham is that in this deposition, Baker repeatedly disclaims specific memory of whether Sussmann identified his clients. Baker’s congressional deposition takes place over two separate days, a couple of weeks apart, and the matter comes up a few times. He is quite consistent that he does not remember Sussmann mentioning his clients, but he also does not state that Sussmann said he had no client interests—and Baker repeatedly suggests his own memory on the subject may be imperfect. The matter first comes up on Oct. 3, when Baker has the following exchange with Democratic staff of the House Oversight Committee (p. 53):

Q. Okay. So when Mr. Sussman came to you to provide some evidence, you were not specifically aware that he was representing the DNC or the Hillary Clinton campaign at the time?

A. I don’t recall, I don’t recall him specifically saying that at the time.

Baker makes clear there are a bunch of facts about the interaction that he doesn’t remember all that well—which is hardly surprising, given that it was presumably not a meeting he expected to have to testify about years after the fact. He says, for example, that he doesn’t remember whether Sussmann told him in advance what he was coming over to talk about (p. 99) and that he wasn’t sure whether it was Bill Priestap or Pete Strzok to whom he referred the matter, though he thinks it was Priestap and knows he did it “within minutes” (pp. 99-100). He says he does not recall whether the FBI agents conducted a subsequent interview with Sussmann (p. 100). Someone at the FBI told Baker to ask Sussman to reach out to his press contacts to stall the story until the FBI could scrub the data, but Baker says he does not remember specifically which FBI official did that (p. 110).

Importantly, Baker also does not clearly disclaim knowing that Sussmann had a professional relationship with the DNC and the Clinton campaign. Asked by Rep. Jim Jordan whether Baker “knew when Sussmann was giving this information ... that he did extensive work for the DNC and the Clinton campaign,” Baker responded: “I am not sure what I knew about that at the time. I remember hearing about him in connection—when the bureau was trying to deal with the hack and investigating the hack, that my recollection is that Michael was involved in that process to some degree. I didn’t interact with him on that, so I am not sure if I knew that before this meeting or after, but I don’t recall him specifically saying—”

Rep. Mark Meadows at this point cuts Baker off and they have the following exchange:

Meadows: But you said you were friends with him, right?

Baker: Yes, sir.

Meadows: So, I mean, you knew what his career was.

Baker: Generally speaking.

Meadows: And you knew, generally speaking, that he had some involvement with the DNC.

Baker: Yes.

Baker’s follow-up deposition on Oct. 18 is more explicit on the relevant point.

At one point (pp. 122-123), Jordan asks specifically, “And was he representing a client when he brought this information to you? Or just out of the goodness of his heart, someone gave it to him and brought it to you?” This leads to the following exchange:

Baker: [I]n that first interaction, I don’t remember him specifically saying that he was acting on behalf of a particular client.

Jordan: Did you know at the time that he was representing the DNC in the Clinton campaign?

Baker: I can’t remember. I have learned that at some point. I don’t—as I think I said last time, I don’t specifically remember when I learned that. So I don’t know that I had that in my head when he showed up in my office. I just can’t remember.

Jordan: Did you learn that shortly thereafter if you didn’t know it at the time?

Baker: I wish I could give you a better answer. I just don’t remember.

It is hard for me to understand how a criminal case against Sussmann can proceed in the face of this testimony. If Baker gave testimony to the grand jury remotely as equivocal as this, then the claimed facts in the indictment are unsupportable. In this deposition, after all, Baker does not testify that Sussmann had told him he was not representing any client, as the indictment alleges on page 18. Rather, he testified that he did not recall Sussmann mentioning being there on behalf of any client, though he says he may have been generically aware of Sussmann’s relationship with the DNC on cyber matters. If, conversely, Baker gave grand jury testimony significantly more confident than this congressional testimony about Sussmann’s disclaiming any client representation, Sussmann’s lawyers will have a field day on cross-examination exposing the differences and attacking the credibility of Baker’s testimony at trial. Either way, it won’t be good for Durham’s case.

There are problems with the corroborating accounts too. I’m not sure how prosecutors mean to get Priestap’s notes admitted as evidence. Priestap’s testimony, after all, will be hearsay—that is, an account not of what the witness saw happening but of what he heard Baker say about the conversation with Sussmann. But assuming the notes come in, they do not support the idea that Baker and Priestap were entirely naive about whom they were dealing with. The note immediately following the one recording that Sussmann said he was “not doing this for any client,” according to the indictment, reads as follows: “Represents DNC, Clinton Foundation, etc.” That tends to suggest, as Baker testified in 2018, that Baker had at least a generic familiarity with the client list of the person with whom he was dealing.

Even the meeting with the other agency doesn’t cleanly corroborate the allegation that Sussmann lied to Baker. According to the indictment, Sussmann sought a meeting with the general counsel of “Agency 2” after the election, and later met with two officials of the agency and gave them Alfa Bank material. In this meeting, on Feb. 9, 2017, Sussmann allegedly repeated the same lie, saying that while Perkins Coie had the DNC and Hillary Clinton as clients, this work had nothing to do with that.

Oddly, however, for someone who was trying to hide his clients, Sussmann had been candid that he was representing “a client” in his efforts to secure this meeting. In reaching out to a former employee of the agency in question only a week earlier, the indictment says, he clearly acknowledged operating on behalf of the client.

My point here is not to defend Sussmann on the charge of lying. Baker is a person of the highest integrity, and if he told the grand jury that Sussmann told him he was operating on behalf of no client and that Baker felt misled by that, I have no doubt that is an accurate account of his memory. My point, rather, is that a defense lawyer has an enormous amount of grist here to attack. Sussmann is well represented by attorneys at Latham & Watkins. The record is muddy. And a Washington, D.C., jury is not a friendly audience before which to prosecute a lawyer who brought material about Donald Trump to the FBI.

So What Is This Really About?

Nothing I have said so far is news to John Durham. He knows what Baker testified in his deposition. Judging from his defensiveness on materiality, he knows he’s got an issue there too. So what is he up to here?

I think the Sussmann case—particularly given the lengthy and irrelevant verbiage about the efforts of the Clinton campaign, its lawyers, cybersecurity experts and private investigators—is an effort to pressure Sussmann to cooperate with a broader effort to prosecute Clinton-world operatives for an attempt to defraud the FBI on Trump-Russia matters. This effort brings together the so-called Steele dossier material with the Alfa Bank story and various other stories that were, at different times, peddled to the press and the bureau. The bet, I suspect, is that Sussmann will cave and make some kind of deal. At a minimum, I agree with McCarthy that taking the investigation in this direction will give Durham a fair bit to write about in a final report. After all, the Clinton campaign was surely engaged in an extensive opposition research effort, the details of which we can expect to be unflattering given everything that is now publicly known.

But there are two big problems with this approach. The first is that digging dirt on political opponents and trying to interest law enforcement in that dirt is not presumptively a crime. It’s presumptively the ugly normal of political campaigns. In the particular case of Donald Trump, who in fact had extensive connections with Russia about which he was actively lying, it was also a perfectly valid line of opposition research. While one cannot peddle information one knows to be false to the FBI without violating the law, that is not what Durham is alleging here about Sussmann.

More fundamental, however, is the fact that the Russia investigation in the main did not turn on these efforts or flow from them. The Alfa Bank investigation in the bureau went nowhere. The Steele dossier affected only the Carter Page matter, which was only one relatively unimportant thread of the larger Russia investigation. While a bad Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) application is always important, the errors in the Carter Page FISA matter did not affect anything beyond the surveillance of Carter Page.

Indeed, none of what we think of as the fruits of the Russia investigation had anything to do with Clinton-world opposition research efforts. Not the Papadopoulos matter. Not the Michael Flynn investigation. Not the investigation of Paul Manafort and his business relationship with the Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik. Not the indictment of Russian intelligence officers for hacking and dumping Democratic emails—all with the public endorsement of Donald J. Trump. Not the investigation of Roger Stone. And not the indictments of other Russian operatives for social media manipulations. The extensive findings of the Mueller report depend not a whiff on Perkins Coie or Fusion GPS.

Not even if Michael Sussmann lied to Jim Baker about his clients.