State Practice and Armed Confict with Non-State Actors

Nigeria seems to have just added some state practice to the debate about whether and when an armed conflict exists between a state and a terrorist group. On Tuesday, the Nigerian Army’s Chief of Staff instructed his forces to consider themselves to be in an armed conflict with Boko Haram.

Nigeria seems to have just added some state practice to the debate about whether and when an armed conflict exists between a state and a terrorist group. On Tuesday, the Nigerian Army’s Chief of Staff instructed his forces to consider themselves to be in an armed conflict with Boko Haram. The extremist Muslim group, which seeks strict implementation of Islamic law throughout Nigeria, is thought to be behind about a dozen terrorist attacks in Nigeria since 2010. The attacks, mostly in the form of bombings and shootings, have targeted police stations, barracks, markets, churches, and the UN headquarters in Abuja. There are scattered reports about contacts and growing relations between Boko Haram and Al Qaeda in the Magreb (AQIM). However, in recent testimony before the SFRC, the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs noted that the State Department has been careful not to conflate the two groups.

What should we make of this apparent paradigm shift to a non-international armed conflict between Nigeria and Boko Haram? Assuming that the Army Chief of Staff is authorized to make this decision (and that his language was not simply rhetoric), it represents the latest in a line of examples in which a state has assumed a military posture toward a non-state group whose tactics rely heavily on terrorist attacks. The Transitional Federal Government in Somalia is effectively engaged in an armed conflict with al Shabaab (a group that one might consider a terrorist group, an insurgency, or both), and in January 2010 the Yemeni Government declared itself to be in an armed conflict with AQAP.

This development provides another data point in thinking about how severe attacks against a state must be before that state may consider itself to be in an armed conflict with the group orchestrating the attacks. There are a number of factors that bear on the existence of a non-international armed conflict. Many look to the ICTY’s Tadic opinion, which concluded that an armed conflict exists where there is “protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organized armed groups.” Yesterday’s declaration doesn’t mean that Nigeria could not have considered itself to be in an armed conflict before now, but it represents one state’s view that this level of violence (taking into account factors such as its duration, intensity, frequency, types of weapons used, and number of casualties) is sufficient to constitute an armed conflict. Of course, a state's determination about whether it is or is not in an armed conflict is not definitive; whether a particular situation between a set of actors constitutes an armed conflict requires an objective assessment.

Assuming that it is legally possible for a state to be in a NIAC with a terrorist group whose organization and quantum of attacks meet recognized international law standards, the Nigerian Chief of Staff's announcement implicates a related debate. Even if lawful, is it good policy for Nigeria to respond to terrorist attacks using military force rather than law enforcement tools? The United States may take Tuesday’s development as further support for its view that it is both lawful and, in some circumstances, necessary to resort to military force against terrorist groups. States and commentators that object to this approach may view the Nigerian Army’s announcement as a manifestation of the slippery slope problem they have warned about.

Ashley Deeks is the Class of 1948 Professor of Scholarly Research in Law at the University of Virginia Law School and a Faculty Senior Fellow at the Miller Center. She serves on the State Department’s Advisory Committee on International Law. In 2021-22 she worked as the Deputy Legal Advisor at the National Security Council. She graduated from the University of Chicago Law School and clerked on the Third Circuit.

More Articles

-

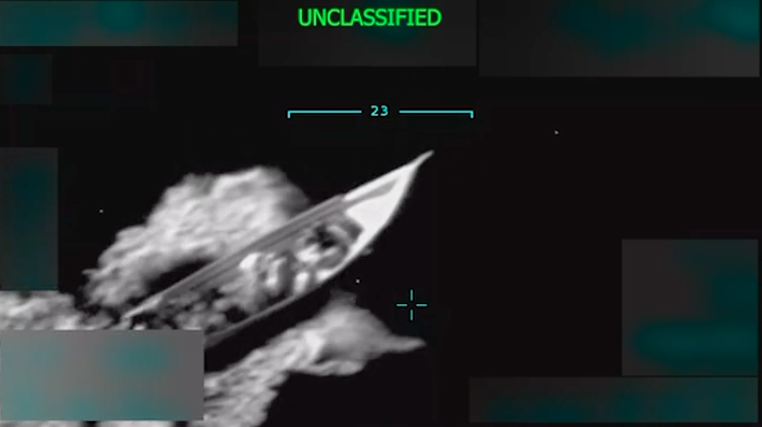

Trump Offers First Legal Justification for Venezuela Boat Strike

The 48-hour War Powers report claims the president acted on the basis of his Article II authority as an act of “self-defense.” -

Did the President’s Strike on Tren de Aragua Violate the Law?

By applying the tools of war to civilians, the Trump administration is entering unprecedented—and deeply problematic—legal territory. -

Lawfare Live: U.S. Military Conducts Lethal Strike on Venezuelan ‘Drug Boat’

Join the Lawfare team at 2:30 pm ET for a discussion of U.S. military activity in the Caribbean.