The Chinese Military Is Built for Politics, Not Fighting Wars

Can China’s military defeat the U.S. military? Think tanks have warned that China’s military forces could prevail against U.S. forces. War games, which claim to simulate how such a conflict could unfold, have generally concluded that Chinese forces could either defeat U.S. forces or inflict such crippling losses that the United States would win (at most) a pyrrhic victory. The finding that China’s military could beat the U.S. military has been replicated so often that it has become conventional wisdom. Senior U.S. military officials, echoing the accepted wisdom, have repeatedly warned that China’s military can beat the U.S. military.

These claims deserve closer scrutiny. In almost every single study, war game, and warning, the hypothetical conflict in question is the same: a clash in the Taiwan Strait. These sources also unanimously regard the quantity and quality of Chinese armaments as the decisive factor. In particular, China’s advanced surface-to-air and anti-ship missiles, with a modest contribution from its aircraft and ships, threaten to obliterate U.S. military ships and aircraft that operate within their range.

Paradoxically, the fact that it is the Chinese military that operates such weapons is almost irrelevant. Any country that owns a large inventory of these weapons could pose the exact same threat to U.S. forces. This point is underscored by reports from weapons experts, which characterize this threat as one of “anti-access, area denial” and acknowledge that any other country in the world that operated such missiles in similar numbers would pose the same threat to U.S. forces.

What makes China a unique threat is not these weapons specifically, but rather its wealth and geography. As the second largest economy in the world with a USD$249 billion defense budget in 2025, China can purchase these weapons in massive numbers. Each missile costs a mere tens of millions of dollars, and China already has thousands of anti-air and anti-ship missiles in its inventory. As for its geographic situation, the country has the most ideal location imaginable for employing such weapons. China’s military could use its large inventory of anti-air and anti-ship missiles to deny U.S. military access to the air and waterspace around Taiwan, an island flash point located just off its coast, that is also thousands of miles away from U.S. shores.

These features make the danger posed by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) significantly different from America’s past most dangerous great power rivals. The threat posed by the German Wehrmacht in World War II, for example, did not stem from the technology of its tanks, aircraft, and ships—all of which were of arguably inferior quality to that of America and its allies, at least in the early part of the war. What made the Nazi war machine so formidable was the size of its military combined with its tactical and operational brilliance, its expert military leadership, the impressive discipline and professionalism of its troops, and the utter ruthlessness of its political leadership.

Most would agree that the Chinese military is not superior to the U.S. military in such intangible but critical factors. Indeed, analysts have concluded that in virtually any other scenario outside the protective envelope of China’s land-based missiles near Taiwan, China’s military forces would probably fall to U.S. military forces. Chinese military forces that operated outside the protection of its land-based anti-access, area denial missiles would, after all, be extremely vulnerable to coordinated attacks by U.S. forces deployed from allied bases. Without the aid of its land-based missiles, Chinese military forces would have to rely on their military leadership, proficiency in executing joint operations, training and knowledge of modern war, and command culture to outfight their American counterparts. In all of those areas, China’s military compares unfavorably to the U.S. military. This fact alone raises serious questions about China’s ability to prevail against the U.S. military.

One could counter that potential defeats of the PLA outside the Taiwan Strait are irrelevant because such a war would unfold entirely around the island. This is almost certainly wrong. History consistently shows that when great powers fight, their wars spread geographically and last a long time. A U.S.-China war would likely unfold around the world, involve contending coalitions, and last many years. China may very well hold an advantage in an opening clash near Taiwan, but its prospects appear doubtful anywhere else. China has no overseas military bases to defend from, other than Djibouti. Thus, PLA forces abroad would have to operate from the sea, making them vulnerable to U.S. submarine attack or strikes by U.S. forces from allied bases. Or PLA forces would have to operate from China’s base in Djibouti or any other military post they may have established. These facilities would likely be few in number, have limited defensive capabilities at best, and would be extremely vulnerable to attack by U.S. forces.

The U.S. defense community risks making the same mistake about China’s military that it has made about past adversaries such as Iraq—vastly inflating their combat potential and exaggerating their ability to outfight the United States and its allies. The error in all of these cases is the assumption that the acquisition of hardware directly translates to increased combat capability. Indeed, these two issues are separate. Nothing is more common throughout the developing world than dictators armed to the teeth with gleaming, advanced hardware. But when it comes to using the hardware in combat, too often the same dictators experience shocking setbacks and humiliating failures. For example, Saddam Hussein’s military was routed in both 1991 and 2003 despite having more troops and tanks than the U.S.-led coalitions, and Vladimir Putin failed to quickly subdue Ukraine when Russia invaded in 2022, despite an apparent overwhelmingly superior military.

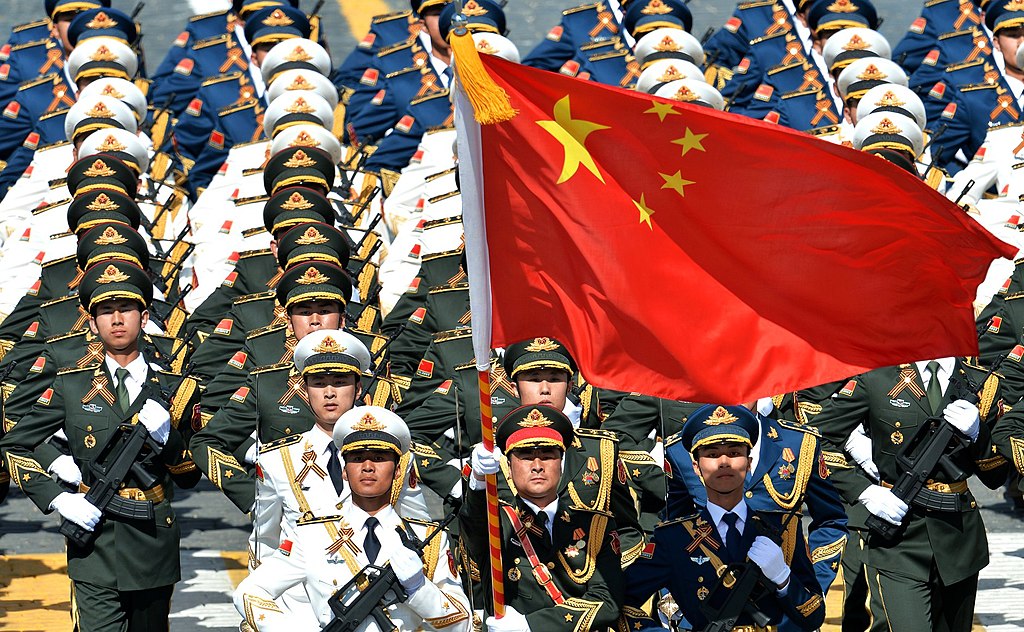

When there are so many militaries equipped with advanced hardware, why do so few of them fight well? The answer is that the vast majority of militaries resemble that of Iraq’s: They are organizationally and operationally optimized to promote domestic and regime security, not fight wars against well-trained professional militaries. These militaries may have modern weapons, but they tend to select commanders based on loyalty, not merit, and the forces are subject to political controls, indoctrination, and surveillance to reduce risks of coups. These militaries may be involved in commercial enterprises to aid the nation’s economic development or supplement meager incomes. Many militaries, ranging from Saudi Arabia to North Korea, hold military parades and lavish exercises to showcase their advanced armaments, instill patriotic pride, and warn potential adversaries. Some militaries in the developing world do fight, but their adversaries tend to be domestic enemies. War between countries remains rare. In 2023, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence estimated that there were approximately 30 intrastate wars, another 30 internationalized intrastate wars, and only five interstate wars. In Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, and Peru, militaries have battled drug cartels. In many countries in the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa, militaries battle separatists, coup plotters, rebels, and other insurgents. Some of these insurgents may be well equipped, but they generally tend to have little professional military training and fight as irregular forces.

All of these tasks can bolster international prestige, help a regime maintain its grip on power, and/or bolster the credibility and appeal of a government. None of them, however, requires the military to be able to be an effective warfighting machine. “Political militaries” that prioritize domestic stability and regime security may be well equipped with impressive hardware, but they are not organizationally and operationally optimized to fight conventionally equipped, well-trained foreign militaries.

A small minority of militaries prioritize warfighting skill. These militaries—of countries such as the United States and Israel—may be called “warfighting militaries.” They tend to share several features in common: They uphold a professional military ethos, favor merit-based promotions, undergo rigorous and realistic training, and prioritize war preparations against well-trained foreign enemies that operate conventional, as opposed to irregular, forces. Warfighting militaries fight well, and their operational proficiency means they can simultaneously handle many of the kinds of non-war missions undertaken by political militaries such as disaster relief, stabilization operations, and counterinsurgency. However, unlike political militaries, warfighting militaries are poorly suited to political missions to ensure regime security. They are likely to resist demands to carry out the types of activities undertaken by some political militaries, such as attacks against their fellow citizens, ideological indoctrination, domestic police duties, or staged events and parades to demonstrate fealty to the top leader. When President Trump ordered the U.S. military to patrol streets in U.S. cities, for example, former U.S. military officials filed a lawsuit against the operations, warning that such missions would harm the U.S. military’s morale. Trump’s deployment of U.S. troops to the border, patrols in U.S. cities, and role in counternarcotics operations has spurred sufficient consternation within the ranks that Secretary Pete Hegseth has had to repeatedly purge the military’s senior ranks.

Like Iraq, Russia, and, frankly, most militaries in the world, the People’s Liberation Army is a political military—not a warfighting one. Every aspect of the PLA has been optimized to uphold Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule. Its mission statement, the so-called historic missions, states that the PLA’s top priority is to “resolutely uphold the leadership of the [CCP] and the socialist system.” This shouldn’t be surprising, given that the PLA is the armed wing of the CCP. The political nature of the Chinese military is also evident in its leadership, structure, and organization, all of which prioritize party control and political loyalty above professional competence. For example, politically trained commissars share authority with commanders; party committees must approve all major command decisions; and military personnel spend up to 40 percent of their training time in political indoctrination, in which soldiers must study speeches and commentaries from CCP press on topics ranging from economic development to Marxist ideology. In short, the PLA’s research, training, operations, and activities all prioritize political work or at least allocate a large amount of time and resources to the cultivation of political loyalty.

To be clear, a military that prioritizes politics does not inherently doom it to battlefield failure. America’s own recent retreat from Afghanistan demonstrates how poorly equipped but zealous troops can prevail against adversaries with superior kit. However, enthusiasm and zeal work best when executed by irregular troops. Insurgents and guerrillas are prime candidates for an effective fighting force motivated by political, ideological, religious, or other ideals. As Martin Van Creveld observed, military inferiority paradoxically provides a strong morale advantage. For a fighting force with inferior weapons and equipment, every battlefield setback simply underscores the adversary’s material advantages, while every victory becomes an energizing affirmation of the cause espoused by the weaker side. Political indoctrination can be an asset, not a liability, for these forces. This is further strengthened by the fact that the technical requirements for irregular combat also are far lower than for conventional combat operations. Rather than coordinated, complex maneuvers involving air, naval, and/or ground forces and strikes with technologically sophisticated, precision-guided munitions enabled by space-based and other sensors, irregular forces rely on simpler tactics and techniques such as ambushes, mines, assassination, and raids. These forces can also use their knowledge of terrain and ability to blend in with the populace for an asymmetric advantage. The most famous military underdogs have employed such methods, including the Viet Cong in the U.S.-Vietnam War, the Taliban in Afghanistan’s war against the Soviet Union, and in China’s own experience, when the Mao-led Red Army defeated the Kuomintang in the Chinese Civil War.

In contrast to irregular forces, conventionally equipped political militaries tend to perform poorly when they fight warfighting armies, however. Time spent on political indoctrination limits troops’ professional knowledge, hampering decision-making. Coup-proofing measures such as over-centralization and divided commands also tend to slow decision-making, reduce battlefield efficiency and agility, and increase the likelihood of disastrous mistakes. The downside to owning a modern military equipped with advanced weaponry is that they are incredibly difficult to use well. Their potential can be fully realized only when backed by an appropriate infrastructure of logistics, institutions, and support capabilities and when operated by professional, highly skilled troops—that is, the kinds of troops found in warfighting militaries.

History provides only a few examples in which ideologically motivated conventional militaries fought well. In World War II, Soviet, German, and Japanese armies combined professional military with ideological training yet fought well. In each case, leaders tended to carefully balance the need for combat effectiveness with the imperative of ensuring political reliability. In other cases, the beneficial effects of political indoctrination on combat skill can be overstated. For example, when the Red Army’s divided command system began to impair its battlefield performance, Joseph Stalin demoted political commissars and instituted a unitary command system. As a result, the Soviets improved their battlefield effectiveness after 1942 and crushed their German adversaries. Similarly, the Wehrmacht’s impressive successes owed far more to the German military’s tradition of combat skill and professionalism than to Nazi ideology. The German army established its battlefield prowess well before the Nazi regime in the ruthless fighting of World War I, after all. During World War II, the Wehrmacht’s elite regular army units tended to fight just as well as the most elite ideologically driven Waffen SS units.

For countries with insecure regimes, realizing the full combat potential of their military forces is even more difficult. Due to their political fragility, such governments tend to regard the military as both a potential threat to and potential asset for perpetuating their rule. To deter rival elites, rulers of such militaries adopt coup-proofing measures such as the division of command, the promotion of loyalists, political indoctrination, and the centralization and/or fragmentation of command and control. Saddam carried out such measures prior to his war with Iran and before the Gulf War and subsequently suffered catastrophic battlefield failures. Similarly, Joseph Stalin purged most of his professional military leadership right before World War II. When the Germans invaded in 1941, the Soviet army lost 2 million men amid numerous disastrous battlefield defeats. These measures can improve a military’s reliability and reduce the potential threat of a coup. However, they invariably come at the cost of reduced combat effectiveness. Indeed, the more a military prioritizes political reliability and loyalty, the worse its combat performance tends to be.

China’s military serves a politically insecure CCP regime. The intractable problems of surging unemployment, a gloomy economic outlook, pervasive corruption, and meager social welfare services has sapped popular support for CCP rule. The vast sums spent on internal repression, which since 2011 has surpassed the defense budget, hint at the government’s fears of domestic unrest. Like other political militaries, the PLA accordingly prioritizes social stability and regime security, posing a serious dilemma for Beijing. Chinese leaders urgently seek a loyal and dependable military to keep the CCP in power. Yet they also hope to build a competent military to deter potential adversaries. A military can excel at one function but not the other. Or the military can attempt a mediocre balance of political and warfighting functions at the same time.

China’s resolution to this dilemma is revealed in its rapid nuclear weapons buildup. Over the past five years, China has doubled its nuclear arsenal, and the U.S. government estimates China will have 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030. As U.S.-China tensions increase, the risk of conflict, although remote, cannot be completely discounted. China’s military might well enjoy a win in an initial clash near Taiwan, but America’s warfighting military would very likely have a tremendous advantage against China’s untested and thoroughly politicized military over the course of a long-term, global war. It is at this point probably futile for the PLA to hope to catch up to the U.S. military as a lethal warfighting machine, especially since the PLA cannot escape the more urgent political duties imposed on it by the Chinese leadership. Therefore, nuclear weapons provide the simplest and most direct means of upping the credibility of China’s military power without forcing painful and difficult changes needed to become a warfighting military such as dismantling political controls and building a command system that favors battlefield effectiveness over political reliability.

Saddam’s sordid demise provides an illuminating example. The lesson is not that Iraq should have built a superior conventional military that could outfight the U.S. military—something that was well beyond Iraq’s capacity and probably beyond the capacity of every other country on the planet. The lesson is that Saddam should have built the nuclear weapons that Washington incorrectly accused him of harboring in the first place. Saddam could have threatened to use nuclear weapons if the U.S. military attacked him. This would have forced the United States to consider retaliating with its own nuclear strikes. The terrifying prospect of an escalating nuclear war in the Middle East would undoubtedly have given policymakers in the United States and its allies in Europe and the Middle East a compelling reason to reconsider invading Iraq.

Other countries have learned this lesson well. North Korea’s Kim Jong Un has maintained his grip on power despite the dilapidated state of his military, thanks to a growing nuclear arsenal. Russia has similarly relied on its nuclear weapons to compensate for the declining credibility of its corrupt and shambolic military. China’s military is expanding, but it remains untested, riven by corruption, and focused on keeping the CCP in power. With nuclear weapons, China, Russia, and North Korea can deter war with the United States without forcing their political militaries to undergo the painful changes necessary to becoming warfighting militaries.

Could things change in the future? How could one tell if, despite its nuclear arsenal, China decided to build a military capable of fighting the U.S. military head on in a large-scale conventional war? The most important and difficult changes would involve dismantling political controls and adopting measures that instead prioritized combat effectiveness. These could include the elimination or demotion of commissars as the Soviets did in World War II. Party committees could be abolished or their authority severely restricted. The PLA could reduce or eliminate political indoctrination to maximize time spent on rigorous, realistic combat training. Promotion criteria might be modified to favor merit instead of political loyalty. Doctrine and command procedures could be modified to encourage initiative, risk-taking, and combat effectiveness at the cost of looser political controls. What’s more, a Chinese military intent on combat excellence would want to test out the effectiveness of such changes and thus probably aim to provoke at least a small-scale clash with a neighbor before taking on the U.S. military. Such changes are not impossible, but they would require huge political risks, the most important of which is the heightened danger that a powerful, capable military with little loyalty to the CCP could turn against the regime itself.

Although war games raise questions about America’s ability to prevail in a fight near Taiwan, such conflict scenarios tell us more about the lethality of modern missile systems than they do about China’s military. Moreover, such war scenarios play to American, not Chinese, strengths. As a warfighting military, the U.S. military will seek ways to prevail on the modern battlefield, no matter how challenging. By contrast, the PLA, as a political military, will in all likelihood favor the avoidance of war with a premier warfighting military if possible.

U.S.-China tensions could well escalate into a conflict some day. If they do, Beijing has little incentive to repeat Saddam’s mistake of risking open battle with the U.S. military. China also has far better options. The U.S. military’s record against conventional military opponents is the envy of the world, but its record in unconventional wars is far less lustrous. Relying on nuclear weapons to deter a conventional war, China could instead fund, arm, and equip adversaries of U.S. allies and partners around the world. This could, in turn, force the United States to drain its resources to aid embattled friends or forswear any help and thereby tear up its network of alliances and partnerships. Given the CCP’s own historical successes with irregular warfare, such an approach to fighting a superior U.S. military could well prove irresistible. China will continue to pose a serious challenge to the United States, but the Chinese military’s ability to defeat the U.S. military on the modern battlefield should not be exaggerated.

.jpg?sfvrsn=104df884_5)