The Situation: Another Day, Another No True Bill

As Bob Dylan once sang, “How many grand juries must reject an indictment before we call it a no true bill?”

The Situation on Monday contemplated the White House’s new National Security Strategy, a subject about which I had an extended conversation yesterday on Lawfare Live: The Now—a conversation which, by the way, proudly featured the most flubbed introduction to anything I have ever given:

My flub, it turned out, was comparatively minor. Because yesterday also saw the Justice Department trying—yet again—to obtain a grand jury indictment of Letitia James and failing—yet again.

As Bob Dylan once warbled, “how many grand juries must reject an indictment before we call it a no true bill?”

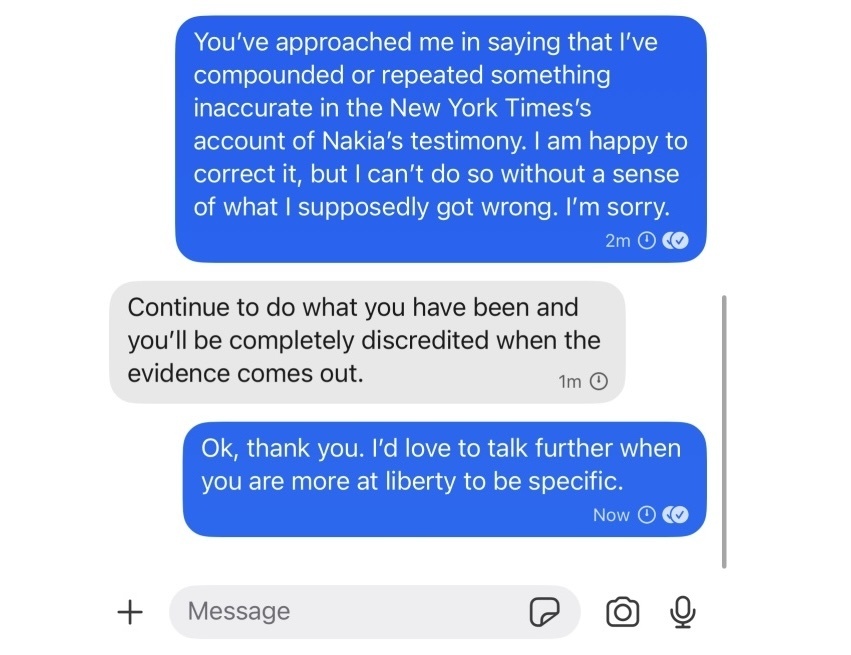

It was only a few weeks ago that Lindsey Halligan—the unlawfully appointed U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of Virginia, who still somehow purports to be running the office despite court rulings declaring her service illegal—was texting my colleague Anna Bower, promising that the evidence in the James case would humiliate Bower when it became public: “Continue to do what you have been and you’ll be completely discredited when the evidence comes out,” Halligan wrote to Bower less than two months ago.

Bower has continued to do what she had been doing, which is to say reporting and asking questions, and the evidence has now come out—to two separate additional grand juries, both of which rejected Halligan’s invitations to re-indict James.

One of Anna Bower and Lindsey Halligan has been completely discredited, and it seems to me that it ain’t Bower.

All of which brings me to a question that has been bothering me about this whole episode: How many strikes does it take before you’re out in the federal prosecutor game?

Okay, yeah, this isn’t baseball, I get it.

But traditionally, the American criminal justice system has not understood this fact to mean that the prosecutor gets an infinite number of swings at the grand jury ball. Rather, the traditional interpretation—and it’s a normative interpretation, not a legal one—has been extremely conservative: A prosecutor should never swing and miss before a grand jury. And if, for some reason, she does, that’s the end of it. She goes away in shame and the putative defendant gets to go on with her life.

Indeed, the reason that our legal culture has all these jokes about grand juries and ham sandwiches is that we expect prosecutors to bat a thousand in the grand jury context. We expect this not because grand juries are pushovers, which we have learned in the last few months they are not, but because federal prosecutors observe certain professional standards before them.

The result of this expectation, which the Justice Department across administrations has nearly always met in modern decades, is that our society has not really had to address the question of how many bites at the apple a prosecutor should get if it simply chooses not to observe professional standards. And what should happen if it keeps swinging.

Well, now we face the question pretty squarely. Halligan and a lawyer she imported from Missouri when none of the Eastern District professionals would work the James case have now brought this case before three separate grand juries. The first time, Halligan obtained an indictment, only to have it thrown out, because, well, she’s not actually lawfully in office at all. To stick with our baseball metaphor, you might say she wasn’t even supposed to be at bat—or on the team at all. The second two times, grand juries rejected her bids for redos. Does she get an infinite number of shots at James before an infinite number of grand juries?

The legal answer to this question is apparently that she does. But the assumptions behind that toleration all seem pretty flawed in the current context.

The first is that we don’t need a rule limiting prosecutorial swings and misses before a grand jury because prosecutors have competing priorities. It’s a busy world of crime out there, after all, and it’s a reasonable hypothesis that prosecutors won’t get so obsessed with any one criminal defendant that they treat the grand jury like batting practice before a pitching machine and just keep swinging.

Reasonable, perhaps, but clearly wrong in the era of the second Trump administration. Even in the first Trump administration, a single strike before a grand jury in the effort to prosecute former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe was enough to bury the case for good. But Halligan is in her “Audience of One Era,” as Taylor Swift once famously labeled it, and there are no competing priorities. She was put in the job to prosecute James Comey and Letitia James, and abject failure on both scores does not have her showing signs of wanting to move on to other things.

Another possibility is that the prosecutor might be limited by her own toleration of the very humiliation she promised Bower. But merely to state this possibility is to reject it—and with a bit of a giggle at that. Let’s just say that Halligan’s toleration for humiliation is robust.

A third possibility is that she might be deterred by the near-certain prospects of failure before a petit jury at trial that serial failures before mere grand juries portends. And again, with a normal prosecutor in normal times this would be—and, indeed, has long been—a fully adequate deterrent. After all, a grand jury operates on a low standard. It indicts based on mere probable cause, based on a mere majority vote, without ever hearing from the defense, and without particular regard for standards of evidence. A petit jury, by contrast, sees a full adversarial trial and then has to convict unanimously based on admissible evidence only after finding of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. If a prosecutor is striking out before multiple grand juries, it follows that her prospects at trial are well nigh hopeless.

There’s a legal element of this point, as well. James had a motion to dismiss pending based on a claim of selective and vindictive prosecution at the time her case was dismissed, because, well, Halligan was not lawfully in office at all.

Every time Halligan takes a swing at a grand jury pitch and wacks herself in the back of the head with her own bat, that motion—should it ever be filed again if some grand jury ever actually indicts—gets stronger. It’s coming now to resemble the motion for vindictive prosecution that Moby Dick might litigate against Captain Ahab. And that fact alone would deter a normal prosecutor from the nth attempt before the grand jury.

But again, when you’re in your Audience of One Era, it doesn’t matter if there are plenty of fish in the sea or if you’re going to look obsessive—and therefore vindictive—to some district judge for focusing on one particular whale halfway around the world to exclusion of every other fish. And it doesn’t matter either if your prospects for success before a jury on the ultimate merits of the case are roughly those of the Pequod on its final journey.

You’re not going to say, as Bob Dylan once put it (for real, this time): “Boys, forget the whale. Look on over yonder. Cut the engines. Change the sail.”

When your boss is Donald Trump and you’re in your Audience of One Era, you never forget the whale.

Never.

And that means you keep swinging at pitches, no matter how many times you miss.

So what is a non-defendant to do when her non-prosecutor behaves like this?

The legal system’s answer, for lack of a better one, is to await exhaustion. I confess I don’t find this a satisfying answer, much less an answer that is likely to restrain the administration in its pursuit of its political foes either in this case or another.

It seems to me the answer has to—one way or another—lie in the supervisory power the courts have over their grand juries. There has to be some point at which the serial presentation of the same weak case before grand juries for purely vindictive reasons constitutes such an abuse of the grand jury process that the court itself has an obligation to intervene, if not to protect the subject of the abuse then to enforce the rules of ethical practice by officers of the court. I don’t know, to be perfectly candid, what such an intervention looks like, whether there is any lawful basis for it, or the mechanism by which the court would even take it on. We are in uncharted territory here. But if I were the chief judge of the Eastern District of Virginia, I would have my eye on the matter.

The Situation continues tomorrow.