Vassals vs. Rivals: The Geopolitical Future of AI Competition

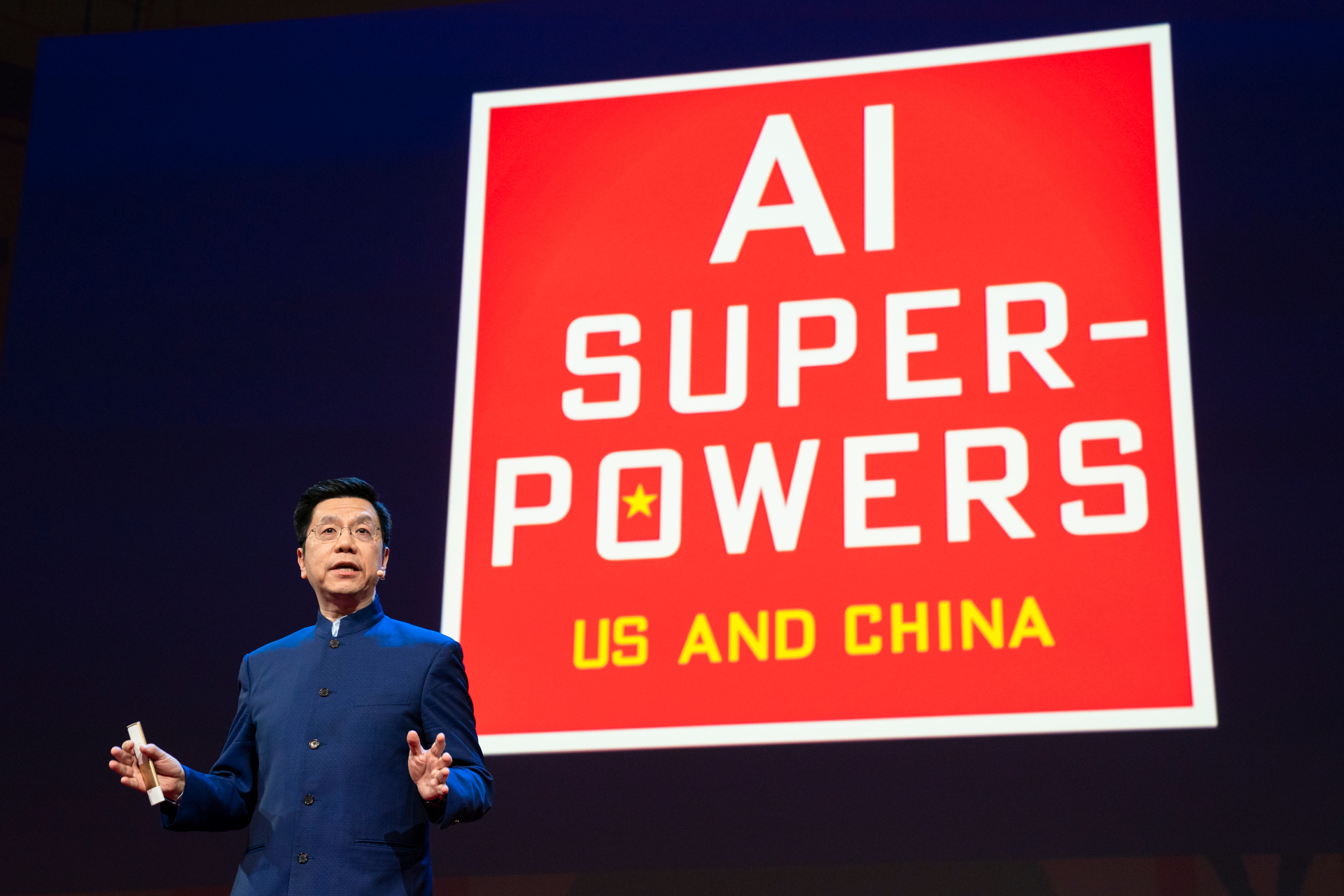

In 2018, Kai-Fu Lee, a Beijing-based technologist, investor, and entrepreneur, predicted a geopolitical future shaped by American and Chinese dominance in artificial intelligence (AI): “[Y]ou might have some countries with no choice but to become a vassal state to the U.S. or China: You got my data, I will do what you want, and you help me feed the poor people.” The Economist characterized Lee’s vision this way: “The world will devolve into a neo-imperial order, in which, if they are to tap into vital applications, other countries will have to become vassal states of one of the AI superpowers.”

Five years later, as large language models—LLMs—like Google’s PaLM 2 and OpenAI’s GPT-4 have begun to proliferate, AI competition has surfaced as a critical part of the broader tech rivalry between the United States and China. Though some analysts echo Lee’s binary view of AI rivalry, the global AI-competitive environment looks less dyadic than the picture he painted in 2018.

Today, there are more nation-state AI competitors than Lee predicted, and a handful of countries are launching new strategies to compete more effectively with the U.S. and China. These government initiatives reach beyond regulating the technology toward a more robust AI industrial strategy. Still, many less AI-ready countries risk falling into Lee’s AI vassal trap—though there are steps they can take to avoid it.

For its part, it is in the U.S.’s national interest to encourage global AI competition and use it as a catalyst for creating a global AI ecosystem that is more open, rule bound, and balanced than it would be in an AI vassal future.

Global AI Competition in 2023

On the surface, the current state of play reflects Lee’s description of a two-way AI race between the U.S. and China. The true nature of AI competition among nation-states, though, is much more complicated and driven by the classic inputs of tech rivalry: talent, capital, infrastructure, data, and software. In 2023, despite the growing trends against global capital, data, and technology flows, none of these catalysts for AI competition is concentrated only in the U.S. and China.

For example, the Global AI Index ranks the U.S. and China first and second in AI implementation, innovation, and investment. But they are not the only countries on the list.

Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Canada round out the top five, and the next five are South Korea, Israel, Germany, Switzerland, and Finland. The Institute for Human-Centered AI at Stanford University (Stanford HAI) produced an AI leadership ranking in 2021 that echoes much of the Global AI Index’s top 10: the U.S., China, India, the U.K., Canada, South Korea, Germany, Australia, Israel, and Singapore, in that order (the countries in italics appear on both top 10 lists).

On a number of measures, the top 10 AI countries are very different from each other. For example, in population size, they range from Singapore, with about 5.5 million people, to China, which has 19 cities with more than 5.5 million residents each. On the other hand, one key commonality among most of the top 10 is that they are open, rule-bound democracies.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) shows a similarly broad range of competition in AI. ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker ranks countries’ competitive advantage based on the impact of their research output. In the subcategory of machine learning, which includes neural networks and deep learning, ASPI ranks China first, followed by the U.S., India, the U.K., South Korea, Germany, Australia, Iran, Canada, and Italy, in that order.

At a high level, AI competition thus appears open to a wide range of countries. Scratching the surface of the Global AI Index reveals not just the openness but also the dynamism of the global AI-competitive environment. For example, India ranks 14th overall but second in AI talent. It doesn’t take much to imagine a world where India moves into one of the top two positions by improving its AI infrastructure, where it ranks 59th, especially given new projects to expand and upgrade the country’s technical infrastructure that have been announced and are underway.

It is also possible that the U.S. and China will separate themselves from the pack, resulting in competition-in-name-only by other countries. For example, ASPI’s tracker shows that the U.S. and China together typically make up about half of the significant research output tracked in AI research. At the same time, the nearest competitor (usually India) ranges from roughly five to seven percent of the academic output tracked in each AI category. On the business front, the Stanford HAI AI Index 2023 Annual Report shows that, of the 1226 newly founded AI companies in 2022, 44 percent were American (receiving $47.4 billion in funding) and 13 percent were Chinese ($13.4 billion). The U.K. was the next closest competitor on a list of 15 countries, at eight percent ($4.4 billion).

Strategies to Stay in the AI Competition

To close the chasm and avoid Lee’s AI vassal future, countries around the world are taking action. More than 60 countries worldwide have developed AI strategies since the late 2010s. Several countries are showing early signs of more aggressive industrial policies as the world is introduced to AI products like ChatGPT and Midjourney. This is perhaps most visible in the efforts by the European Union, Germany, Japan, and others to subsidize the development and production of advanced semiconductors.

Notably, these AI competition policies are separate from—though sometimes related to—efforts to regulate AI in areas like safety, accountability, and transparency. They involve the deployment of capital, technology, and talent to compete, reflecting the recent assessment of French President Emmanuel Macron: “The worst scenario would be a Europe that invests much less than the Americans and the Chinese but starts by creating regulation.”

One way countries are competing in AI is by developing sovereign LLMs, which gives them a deeper understanding of how these models are built, deployed, and leveraged, as well as more influence over AI outside of the regulatory realm.

For example, in March, the Technology Innovation Institute, a research center affiliated with the government of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), announced the Falcon LLM, which reportedly matches the performance of other high-performing LLMs. The U.K. has also considered building a sovereign foundation model, dubbed “BritGPT.” However, in April, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak softened his commitment to the project. Media reports suggest that the Indian government, too, has considered building sovereign AI models.

A second trend has been government support for AI “national champions.” For example, Macron recently announced 40 million euros (about $45 million) in new funding for French AI companies like Paris-based Mistral AI. In June, only four weeks after it was founded, Mistral raised 105 million euros (roughly $113 million) from an investment group that included Bpifrance, a French public-sector investment bank, to compete against OpenAI and other LLMs. This strategy echoes China’s earlier effort to develop Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba as national AI champions.

A third effort underway is the establishment of AI hubs, which are tactically different from each other but share the common goal of attracting AI talent and capital. For example, the UAE open-sourced its Falcon LLM in May. It is offering capital and compute to scientists, researchers, and entrepreneurs who deploy the model for innovative use cases. Open-sourcing Falcon and funding projects that leverage the model may help establish the UAE as an AI leader, attract talent, generate business and strategic opportunities, and improve the model (Meta and other companies that are open-sourcing their own models to one extent or another do so with similar motivations).

The U.K. provides another example of an AI hub. In its case, the plan is to make the U.K. a global hub for AI safety in cooperation with major AI companies like Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic. Though the details are unclear, this effort seems to be aimed at involving the U.K. in the safety component of AI product development. Another example is France’s push to become an AI hub by attracting foreign AI talent through streamlined visa processes to beat other countries to coveted AI talent.

On the infrastructure front, there seems to be a general willingness in most countries to partner with and rely on U.S. cloud companies to train, deploy, and scale LLMs. For several years, U.S. cloud computing companies have been expanding their data centers and broader technical infrastructure footprint throughout the world, sometimes in partnership with local companies (as is the case in France and Germany) and with government support. In the UAE’s sovereign LLM example, Falcon was trained on Amazon Web Services infrastructure, likely in some of the company’s UAE data centers.

As has been the case for several years, however, countries competing in AI will likely seek greater control over foreign infrastructure that supports LLM and other AI workloads. Countries could also move more AI work to government-owned or domestic company-owned infrastructure. For example, France has announced an investment of 500 million euros ($550 million) to increase French and EU computing capacity—including the Jean Zay supercomputer, which is owned by the French government and on which Hugging Face and other organizations trained the Bloom open-source multi-language LLM. The U.K. government has also proposed investing 900 million pounds ($1.2 billion) to build a British supercomputer for AI and quantum-computing advancements.

Given that high-quality data (often in very large amounts) is the fundamental ingredient for an effective LLM, governments are also considering how to use data strategically. The Indian government, for example, has outlined a sovereign AI data strategy. Union Minister of State for Electronics and Information Technology Rajeev Chandrasekhar recently explained the Indian government’s program as one focused on developing bias-free, high-quality, and diverse data sets.

These data sets appear to be designed for use by domestic Indian organizations. They might also be used as a way to raise revenue vis-a-vis foreign AI companies (similar to how Reddit and other companies plan to charge AI companies for access to data for model training). More broadly, curated data sets provided by the Indian government could become a form of soft power—designed to be incorporated by any LLM so that an Indian perspective on language, culture, and other matters is reflected in the model’s output. The French government has discussed moves in this direction as well, focused on investing in AI projects that will use French language data sources to improve model output by, among other things, better reflecting the nuances of the French language.

What Can Less AI-Ready Countries Do?

What happens to countries that are less advanced in tech and less economically developed than those pursuing AI strategies to compete against the U.S. and China? Many less-developed countries of the Global South, for example, are at risk of being left behind and becoming AI vassal states of one or more of the countries succeeding in the AI competition.

These less AI-ready countries may have to play a different game. First, their governments and companies will likely have to be customers (at least in the short term) of foreign AI and integrate the technology into their products, services, and processes. Adoption of foreign AI and developing expertise will be necessary to keep from falling into obsolescence in an AI-driven economy.

Second, these less AI-ready countries might follow India’s lead and look at data—in privacy- and security-sensitive ways—as a differentiator and a means to participate more effectively in the AI competition. For example, developing high-quality national databases that feature language, culture, and other characteristics could be ways to collaborate with other countries on AI, attract AI talent, and generate needed revenue for future investment.

And as open-source AI models and advancements in the development of smaller models progress, these countries might focus on niche areas of AI development where they may achieve a competitive advantage.

The U.S. and other like-minded AI-competitive countries can and should support these efforts with infrastructure, training, and technical assistance.

America’s Leadership Opportunity in an AI-Competitive World

One could conclude that efforts by France, the U.K., India, and others to compete in AI should be seen as detrimental to U.S. interests because stronger global AI competition could reduce an American technological advantage and, thus, American power. However, the diffusion of AI technology and know-how—especially among open, rule-bound, and democratic countries—presents the U.S. with the opportunity to lead a coordinated governance and economic development approach with allies and like-minded partners.

Were the U.S. to hold back other countries attempting to compete in AI, efforts to develop global rules and standards for AI and other digital technologies would become a confrontation between AI haves and have-nots. Many countries would attempt to rein in U.S. AI success by working to create barriers to its digital engagement in the world’s economies.

There is also the risk that, without an open approach that focuses on supporting and partnering with other countries wishing to participate in the AI economy, China would see an opening to build closer ties with U.S. allies and other countries important to U.S. interests.

Finally, AI development outside of the U.S., open-source development generally, and cheaper and faster AI-developing technology together suggest that there may be little the U.S. can do to stop the broad diffusion of current AI technology. At the same time, the global AI competition data shows that the U.S. does not risk losing its leadership position in AI even in a more open and competitive environment.

A U.S. AI policy that is open to global competition and innovation would still require a hands-on approach to various AI challenges and opportunities. For example, the U.S. government would still have an active approach in areas like the use of AI in weapons systems and monitoring and ensuring the safety of frontier models. U.S. policymakers could also work proactively to keep the global AI ecosystem open, steering allies and partners away from the far too common move toward the closed ecosystems of digital sovereignty in the name of strategic autonomy. Beyond that, the current wave of global AI diffusion might prompt policymakers to revisit AI-impacting laws to ensure that they promote openness and collaboration—along with healthy competition—instead of balkanization and division.

The ultimate goal should be digital solidarity: technological self-determination through partnerships and alliances among open, democratic, and rule-bound societies. Given the current technological and geopolitical landscape, this goal could come with an acknowledgment that less democratic countries will need to be part of the solidarity ecosystem for some time and that the balance between partnership and competition will be a tough but necessary one to maintain. Countries in that ecosystem can also ensure that other, less competitive nations are not left behind and are supported in their effort to participate in the AI economy and avoid becoming AI vassal states.

.jpg?sfvrsn=31790602_7)