War and Responsibility: Why the U.S. Doesn’t Have an Imperial Presidency

In an unexpected way, ambition counteracts ambition.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=a6d34b3b_7)

One of the most enduring paradigms in American politics is that of the “imperial presidency,” coined by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in his eponymous book from 1973. The imperial presidency thesis holds that the American executive has accumulated ever-increasing power over time, allowing the executive to bypass the will of Congress. With the Trump administration’s recent rash of executive orders and other unilateral acts, it would seem that the imperial presidency thesis has never been stronger.

While the thesis has been applied to many different areas of both foreign and domestic policy, it is widely held that presidents have much greater power over the former than the latter. Indeed, a related thesis suggests that there is one president but two presidencies: a somewhat constrained presidency in domestic policy, and a much less constrained office in foreign affairs. But even within foreign policy, the “war-making” power has long been singled out specifically as that in which presidential power reaches its maximum. In fact, Schlesinger found this specific power to drive the imperial presidency more broadly, arguing, “The imperial Presidency received its decisive impetus … from foreign policy; above all, from the capture by the Presidency of the most vital of national decisions, the decision to go to war.”

In a newly published piece (“War and Responsibility”) for the American Political Science Review, however, I argue that when it comes to this most core power of the thesis—the war-making power—the imperial presidency falls short. I submit, instead, that the current understanding of the war powers status quo has long been, at best, incomplete, and filled with substantial misunderstanding. In contrast to widespread pessimism toward congressional influence over use of force decisions, I argue that Congress has been exerting considerable constraint on the executive all along; political scientists and legal scholars have just been looking for its influence in the wrong places.

The core of the argument is simple: Presidents do indeed have virtually unlimited discretion in use of military force decisions, but such wide discretion comes with quite considerable political exposure. As is well recognized, it is not difficult for presidents and their lawyers to justify almost any use of force. As Jack Goldsmith has aptly put it for Lawfare, “One person decides.” But this perspective risks overlooking an essential point: Unlimited discretion does not equal unlimited power. Presidents can do whatever they want. But there’s a catch: If they do so—absent a certain level of support expressed by Congress—they are in for a world of hurt if the use of force turns out poorly.

Presidents, in turn, are not fools: They foresee this and are thus deterred from many actions they might otherwise be quite interested in undertaking. These “loss responsibility costs”—and the credible threat of these costs—serve as an invisible hand of sorts, giving lawmakers substantial influence over use of force decisions. This means that lawmakers’ selfish political incentives to avoid use of force votes and to opportunistically attack presidents for failed ventures counterintuitively leads to a socially beneficial outcome: democratic constraint over the use of force.

The Primary Driver of War Powers Behavior: Loss Responsibility Costs

It is widely recognized that on the rare occasion presidents seek formal authorization for the use of military force from Congress, they do so for “political” reasons rather than “legal” ones. As Schlesinger put it, presidents would seek formal approval from Congress “because a resolution, by involving Congress in the takeoff, might incriminate it in a crash landing.” President Lyndon B. Johnson, for example, sought the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution because he knew lawmakers would otherwise “run when the going gets tough,” and he therefore wanted them “tied, bound, and delivered beforehand.” Likewise, President George H.W. Bush opined prior to the Gulf War that lawmakers would “paint their asses white and run with the antelopes” at the first sign of trouble, and hence—in the recollections of his White House counsel—he wanted “these bastards voting with me so that if the thing goes south, they’re with me.” At the same time, it is also broadly realized that lawmakers widely avoid formally voting in favor of the use of force due to a concern of being tainted politically if the intervention then proceeds poorly. Members of Congress want to avoid responsibility.

Hence, the politics of the war powers fundamentally centers on a political hot potato: Who bears the blame if a use of force goes sideways? Presidents seek to implicate lawmakers in the crime, and legislators seek to avoid such culpability. But while these loss responsibility costs are seemingly widely appreciated, their actual implications are rarely fully drawn out. In the aforementioned paper, I use game theory to show that this political posturing between the executive and the legislature implies something quite unexpected: Presidents are constrained significantly by Congress.

Setting up the war powers interaction in game theoretic terms allows one to more easily set out their assumptions of the key pressures and considerations taking place in the war powers space, and then to precisely logically deduce the implications of these assumptions. But understanding the intricacies of game theory is not necessary to comprehend the intuition behind the results: Presidents are vulnerable to loss responsibility costs, and the bigger use of force they undertake, the larger the exposure they face. This gives them great vulnerability when acting unilaterally and effectively incentivizes them to “pull their punches” to limit such exposure. When they have political cover from Congress, however, they are more comfortable using force—and eventually more force. Altogether, this simply means that presidents will undertake larger uses of force only with larger expressions of support from Congress.

For example: Full-scale wars will, de facto, be undertaken only pursuant to formal authorization—the political risk is simply too high to undertake these absent Congress’s formal imprimatur. It does not matter that the White House will claim it has the authority to take such action under the president’s Article II power alone; it is the political risk that deters unilateral large-scale war. Take, for example, Vietnam and Iraq. In both cases, the White House publicly maintained congressional authorization was not necessary (a point supported by executive branch lawyers) but privately saw unilateral entry into major war as politically impossible.

More limited uses of force will be undertaken unilaterally, but really only when pursuant to informal support in Congress:the president is acting not in contradiction to congressional preferences, but pursuant to them. Indeed, lawmakers get to “have their cake and eat it too.” They get the president to intervene but avoid responsibility for the venture. For example, Panama in 1989, the Islamic State in 2014, and Yemen in 2024.

To the extent presidents will act in the face of outright congressional opposition, it will likely be limited to isolated drone strikes, noncombat deployments, mere shows-of-force, and so on. Altogether, these dynamics imply significant constraint on the president, not a lack of it.

This constraint is precisely due to the executive’s exposure to loss responsibility costs—political exposure generated primarily by the threat of opportunistic lawmakers who face strong incentives to attack the executive ex post for any use of force that goes sideways. Hence, the self-interested motives of American lawmakers to be opportunistic and to avoid responsibility whenever possible does not, in fact, lead to an imperial presidency, as frequently alleged. Instead, the political hot-potato of loss responsibility costs yields significant constraint on the president. In an unexpected way, ambition counteracts ambition.

Of course, what works in theory may not work in practice. But history has proved to be quite consistent with these dynamics. The de facto political constraint implied by the deterrent threat of loss responsibility costs is manifested in two ways. First, presidents de facto will avoid entering interventions even remotely approaching full-scale war without formal authorization from Congress. War powers lore often highlights the supposed precedential value of the Korean War, when President Truman entered a war without congressional approval. But—in reality—the lesson executives took from Truman’s unilateral action is that it was political suicide. Second, while it is widely recognized that presidents consistently undertake smaller uses of force unilaterally (again, think Panama in 1989, Libya in 2011, the Islamic State in 2014, Yemen in 2024, and so on), it is rarely appreciated that this is almost always undertaken pursuant to informal congressional support, often in the form of lawmakers’ pressure and urging. It is surprisingly difficult, in contrast, to identify actual combat operations undertaken in the face of congressional opposition.

The Korean War: Legal Precedent but Political Antiprecedent

Regardless of the soaring claims to power made by presidents and their lawyers, American executives are highly averse to entering full-scale wars unilaterally. It is very common to see citations to a supposed Korea war powers precedent, which asserts that presidents are willing and able to enter even full-scale wars without congressional authorization. The problem with this assertion is that presidents after Truman have de facto avoided full-scale wars when they do not have formal authorization in hand—often explicitly pointing to Truman’s experience in Korea. Instead, the Korean War has served for many decades as a strong political antiprecedent.

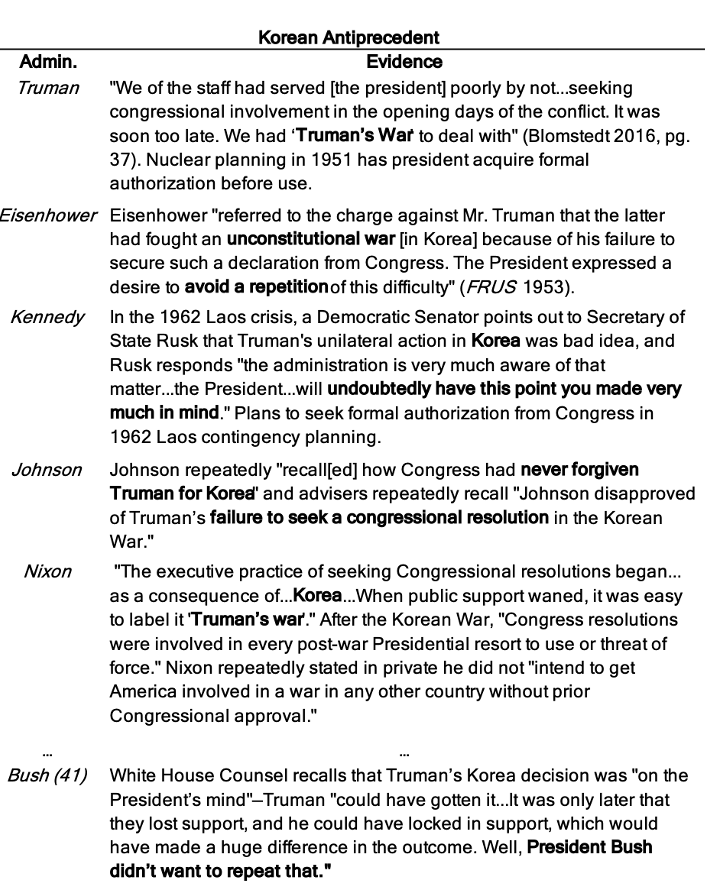

In fact, it is quite clear that administrations subsequent to Truman’s—and even, indeed, the Truman administration itself—came to see the great folly of undertaking a full-scale war unilaterally. It should be recalled that the majority of congressional leaders fully supported Truman acting unilaterally in 1950. The lesson from Korea was that it was highly inadvisable for a president to undertake a full-scale war without formal authorization from Congress. The oft-cited legal precedent was, in reality, strong and explicit political antiprecedent. Figure 1 briefly provides evidence demonstrating this recognition by subsequent administrations quite clearly.

Figure 1. Evidence of Korean war powers anti-precedent.

Since the Korean War, presidents have ventured close to full-scale war only when formal authorization was anticipated. This expands beyond the observation that all major wars after Korea saw a president go to Congress. For example, in examining near-war crises (such as the Cuban missile crisis, the Berlin crisis, or the Taiwan Strait crises), what one actually finds in the evidence is that every time presidents were willing to enter full-scale war, they did so with the assumption they would be acting under formal authorization. At the same time—and in direct contradiction of the assertions of the imperial presidency thesis—there are many instances in which presidents had a strong interest in using military force, but realized authorization from Congress would not be forthcoming, and thus omitted to act. The evidence thus suggests that presidents, de facto, are not willing to enter large, sustained uses of force absent formal authorization from Congress regardless of their broad legal claims to power. Note that in every full-scale war after Korea, the president’s lawyers found the president to have the constitutional power to act unilaterally, and yet every time the president chose against this course.

Smaller, Unilateral Uses of Force: Informal Support in Congress

It is widely appreciated that presidents overwhelmingly use military force unilaterally, although these are consistently “smaller” uses of force. What is much less recognized is that these more limited interventions are nearly always undertaken pursuant to significant informal congressional support—the political risk means that presidents will be reluctant to undertake even these more limited engagements without some backing from lawmakers. Moreover, the reasons these uses of force tend to be undertaken unilaterally is due to the preferences of lawmakers, who often vocally call for the president to intervene but then balk at the prospect of formally voting to authorize the use of force.

Take the counter-Islamic State campaign in 2014. Congress urged intervention against the Islamic State but refused to formally authorize the operation. Republicans assailed the Obama administration for underestimating the danger of the group, with the president infamously calling the group the “JV Team[.]” Then-Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), for example, accused the president of “fiddling while Iraq burns” and called for the president to use American military force to intervene. Pushing for action while avoiding responsibility via a vote was widespread: One Republican representative admitted, “A lot of people would like to stay on the sideline and say, ‘Just bomb the place and tell us about it later,’ … We can denounce it if it goes bad, and praise it if it goes well and ask what took him so long.” One Democratic aide recalled that by pushing for intervention yet avoiding a formal vote, legislators “were in a position where they could shit all over the president … but in no way have to own the campaign.” Former Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes would complain of this typical dynamic: Members of Congress would “press for action but want to avoid any share of the responsibility.”

Hence, in the case of the Islamic State, lawmakers broadly called for intervention but refused to take a formal vote on the matter. The president acted without a specific vote from lawmakers, but this was pursuant to Congress’s preferences, not in contradiction of them. Such a dynamic, moreover, is far from rare—indeed, this tends to far more often than not be what’s going on when the president acts unilaterally.

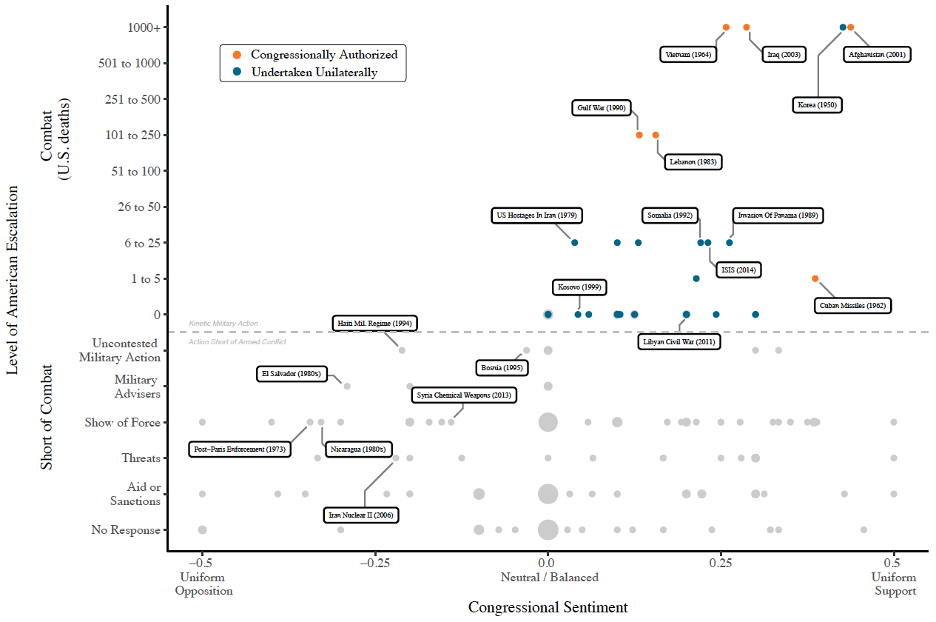

The plot in Figure 2 shows all American foreign policy crises between 1945 and 2022, with the x-axis showing a measure of informal congressional sentiment toward the use of force. This is very similar data to that which I shared on Lawfare a few years ago, making the point that when it comes to informal congressional support for the use of force, the cases are quite consistent with substantial constraint on the president. Even when presidents act unilaterally (the blue dots on the chart below), they almost always do so pursuant to the support and urging of lawmakers.

Figure 2. U.S.-relevant crises 1945-2022, comparing ex ante congressional support for use of force toward escalation level reached.

At the same time, there are episodes in every presidency in which uses of force were seen as “impossible” due to opposition in Congress. Altogether, these dynamics do not suggest an imperial presidency. Again, they suggest an American executive considerably constrained by Congress.

What, then, is one to make of Trump’s recent strike against Iran? It is clear that the politics of loss responsibility costs were at play—one need not look any further than House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries’ first statement after the strike: “Donald Trump shoulders complete and total responsibility for any adverse consequences that flow from his unilateral military action.” One possibility is that Trump is an exceptional president, less politically constrained and deterred than his predecessors. While theoretically possible, there are strong reasons to suspect even the most seemingly unconcerned presidents care about avoiding military disaster, however—for example, a desire to pass a Big Beautiful Bill (a much more difficult task after foreign policy failure), or maintain slim congressional majorities in the next midterm election. Another possibility is that the White House determined the strike to be low risk, given that preceding Israeli actions had demonstrated the total diminution of Iranian military capabilities. Under such circumstances, a president would anticipate quite low exposure to loss responsibility costs and proceed with little hesitation. This is consistent with the theory presented.

Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, recent analyses focused on the legal aspects of the strike risk greatly exaggerating opposition in Congress toward strong action against Iran. Republicans, after all, enjoy unified government at the moment, and GOP lawmakers have long pushed for a tough stand against Tehran. Support among Democrats, moreover, is often overlooked: fully three-quarters of House Democrats joined virtually all Republicans in supporting a 2023 measure declaring it to be the policy of the United States “to use all means necessary to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon.” It was only days before the strike that Senator John Fetterman called for the use of American bunker-busters against Iran’s nuclear sites, and the highest ranking Democrat, Chuck Schumer, had charged the president with being a TACO for failing to take a strong enough stand against Tehran. The episode requires deeper analysis, but opposition to the strikes expressed by progressive Democrats and a few isolated Republicans should not be assumed to represent opposition among lawmakers more broadly. Indeed, this would run directly counter to an extensive literature highlighting the support presidents maintain in the legislature when holding majorities in both houses. Trump is no exception.

Ambition Counteracting Ambition

In summary, the data is consistent with substantial restraint on the president by Congress. True war is undertaken only pursuant to formal authorization from Congress, and smaller uses of force are almost always undertaken unilaterally pursuant to lawmaker preferences (not in contradiction of them, as is often assumed).

Commentary on the war powers status quo is virtually all negative, frequently asserting that there is a wide and growing “imbalance of power” between the branches. It has long been asserted that there has been an “erosion” or “atrophy” of congressional influence in use of military force decisions. Specifically, a common diagnosis of the problem is that lawmakers avoid voting on interventions and “say nothing if the military action succeeds, but...blame the president if it fails.” This, for decades, has led to calls for Congress to “reclaim” its war powers. (John Hart Ely would characterize this prescription as similar to “a halftime pep-talk imploring [Congress] to pull up its socks and reclaim its rightful authority.”) In short, the standard diagnosis has been that the selfish political incentives of lawmakers leads to a lack of congressional influence in the context of the use of military force. Things would be better if lawmakers were angels, not self-interested politicians.

Despite this common diagnosis of the problem, in a strange way it deeply contradicts one of the key insights made by the Founding Fathers two and a half centuries ago. The framers of our government were clear eyed about the system they were setting up—as Federalist #51 would put it, a government of self-interested “men,” not “angels.” The key insight was that a stable government would be made by working with the “personal motives” of politicians, not against them—“ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

It is abundantly clear that the war powers are not working in the specific way likely envisioned by the framers—that is, that uses of force other than true self-defense would be formally approved by Congress. But, ironically, the broader aim of Federalist #51 operates surprisingly effectively even today. Congress’s self-interested political incentives to avoid responsibility and to opportunistically attack the president yield the executive’s exposure to loss responsibility costs. It is the threat of these costs that incentivizes presidents to undertake full-scale war only with legal authorization from Congress, and to closely consider congressional sentiment when acting without it. Hence, the selfish political incentives of lawmakers is not leading to a lack of congressional influence; it is the conduit of great congressional influence. Ambition counteracts ambition, just as the framers intended.

.jpg?sfvrsn=cbb26fe8_9)