What’s Going on at the IRS?

Breaking down the reduction in tax workforce, DOGE’s attempts to access sensitive data, and the politicization and erosion of agency independence at the IRS

According to a recent report from the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, the Internal Revenue Service has lost nearly a third of its revenue agents in only two months. Since the start of the second Trump administration, the IRS has seen massive and unprecedented workforce reductions, the rapid erosion of long-standing data security and privacy protections, and the shift of decision-making power from civil servants to political appointees.

Similar actions are underway across the federal government—but because the IRS raises about 96 percent of all federal revenue, these cuts to the tax agency threaten the capacity of the U.S. government as a whole. The potential damage to federal revenue has been estimated in the hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars over the decade to come.

It might seem surprising that the United States would see a sharp decline in its fiscal capacity as the governing regime becomes less democratic. But, despite the trope that taxation is tyranny, the historical pattern is the reverse. It is representative legislatures, not tyrants, that are good at raising revenue, and it is authoritarians who preside over tax systems that are at once hollow and politicized. The undermining of independent nonpartisan tax administration is an integral component of rising autocracy.

Reductions in Tax Workforce

To date, the IRS has seen at least an 11 percent reduction in its workforce, including the more than 4,000 IRS employees who accepted the deferred resignation program first proposed in the Jan. 28 “fork in the road” email, and the mass firing of over 7,000 probationary employees (an action that has been contested in court but is currently being allowed to move forward).

The cuts have affected IRS offices in every state, with the largest proportional cuts in Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, and Mississippi, where more than a fifth of employees have been terminated. In one Kansas City office, employees have been informed of mandatory full-day overtime on upcoming Saturdays to process tax returns.

The magnitude of these staff reductions is without comparison in the modern history of the IRS. The nadir of the IRS’s effectiveness came in the late 2010s, when chronic underfunding forced the agency to reduce its workforce by an average of 2 percent annually, about one-sixth of the reduction seen so far this year. And the cuts are still coming. Leaked information suggests that administration officials are aiming to reduce the agency’s workforce by 25, 40, or 50 percent in total. Roughly 20,000 IRS employees have reportedly applied for the second round of deferred resignation, offered by the Treasury Department in April; if approved, these separations, plus the terminations that have already occurred, would represent almost one-third of the agency’s workforce.

In addition to dismantling the IRS’s civil rights and anti-discrimination functions, the Trump administration is seeking a weaker tax enforcement system. Under one plan disclosed in March, taxpayer services were slated to see an 8 percent decline in workforce, while compliance was due to be cut by 22 percent by mid-May. Workforce cuts have been particularly severe in the portions of the IRS that enforce tax law for the highest earners. The IRS office investigating pass-through entities, an abuse-prone business structure given preferential treatment in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, had lost 27 percent of its workforce by late March. The Global High Wealth unit, which investigates the personal and business taxes of the very richest people, was until recently slated for major expansion. It has instead lost 38 percent of its staff. The staffing reductions have interrupted ongoing audits on high earners, many of which will likely expire without reaching their conclusion.

At the same time, the administration is attempting to redirect law enforcement from white-collar crime to immigration. In February, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem asked Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to redirect some of the more than 2,000 officers in the IRS’s criminal investigations division, which focuses on financial crimes like fraud and money laundering, to border enforcement. Some IRS employees have been deputized to work on immigration, but it is unclear how many. The Department of Justice also sought to dissolve its tax division but retreated from that plan after widespread criticism from officials and tax law experts. The office’s former head, a 40-year Justice Department veteran, resigned rather than accept reassignment to the new “sanctuary cities enforcement working group.”

The dismantling of the tax enforcement system will likely result in a substantial rise in tax evasion at the top. Most of the annual “tax gap”—the difference between tax revenue owed and tax revenue paid voluntarily and on time, an estimated $700 billion in 2022—is due to underreporting of income by high-earners. More than a quarter of income underreporting comes from the top 1 percent of tax filers. The tax gap grew, not coincidentally, over the decades when the IRS was severely underfunded. In the 2010s, the audit rate for those earning a million dollars or more a year fell by more than 70 percent.

We may also see more audits for lower income people. Conservatives in Congress have long pushed the IRS to root out supposed fraud in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). By 2018, EITC recipients, typically earning $20,000 or less annually, were being audited at rates comparable to those earning upward of half a million dollars a year. These audits tend to be conducted by paper notices, a process that is easy to implement with a small undertrained staff.

Attempts to Access to Sensitive IRS Data

As their initiatives have hollowed out the IRS workforce, Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has moved rapidly and secretively to consolidate control over the immense stores of personal data housed within the IRS, undermining long-standing legal protections for taxpayers’ privacy. This accrual of surveillance and policing power threatens Americans’ civil, political, and economic liberties.

In mid-February, DOGE sought access to the IRS’s Integrated Data Retrieval System (IDRS), which includes names, addresses, ID numbers, and bank information for U.S. tax filers. These demands were the equivalent, according to former IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel, of a newly hired custodian at a bank demanding “the key to every safe deposit box in the vault.” Given the highly sensitive nature of the data, this system is strictly limited to those for whom access is job-essential and—unlike the Treasury payments system operated by the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, to which DOGE at one point had read-write access—DOGE’s IDRS access was limited to anonymized data.

Over the following weeks, however, DOGE continued to push for greater access to IRS systems, at one point seeking personally identifiable tax information to investigate student loan and SNAP recipients. In March, the agency announced that 48 of the IRS’s senior information technology executives would be put on leave. Then, in early April, it was reported that DOGE was holding a “hackathon” at the IRS to kick off a month-long project to build a “mega API” that would allow for easier data exchange between agencies. It is not entirely clear who participated in this “very unstructured” endeavor to rewrite the systems that contain and protect Americans’ tax data. “It’s basically an open door controlled by Musk for all Americans’ most sensitive information with none of the rules that normally secure that data,” one IRS employee told Wired. Records from the IRS and the Social Security Administration are reportedly being combined with biometric data and information from some state voter files in a central repository housed within U.S. Customs and Immigration.

These events would be worrying under any circumstance but are especially so in the context of mistakes at the IRS and reports of data abuse at other agencies. In the lead-up to Tax Day, the IRS website displayed a multitude of errors, which had appeared soon after DOGE publicly celebrated making revisions to the site. At the Social Security Administration, DOGE affiliates demanded that thousands of living immigrants be added to the “death master file” and surreptitiously extracted potentially sensitive data from the National Labor Relations Board. At least seven lawsuits have been filed regarding the access of DOGE to the American public’s personally identifiable data at Treasury and at other agencies.

The Trump administration has been clear in its intention to use tax data for deportations. As early as February, the Department of Homeland Security sought a data-sharing agreement with the IRS. The IRS originally rejected the proposal; the agency has long protected the tax data of undocumented people, who are legally obligated to pay taxes like all other U.S. workers. Since 1996, the IRS has provided Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers, or ITINs, to undocumented workers, who are estimated to have paid $66 billion in federal taxes in 2023. “The IRS has strong processes in place to protect the confidentiality of taxpayer information, and this includes information related to tax returns filed using ITINs,” the IRS said in 2017.

Section 6103 of the Internal Revenue Code tightly defines the contexts in which individuals’ IRS data can be disclosed or even inspected. Section 6103 allows the IRS to share tax information with law enforcement agencies for “investigation and prosecution of non-tax criminal laws,” but many immigration violations are civil offenses, not criminal ones. Moreover, 6103 enumerates specific and very narrow circumstances in which tax data can be used to locate people, and these do not include a provision for immigration enforcement. Penalties for violating 6103 can include monetary damages and prison terms.

Nonetheless, Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the IRS entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) in early April. Tax and privacy law experts have criticized the MOU’s lack of safeguards and described it as likely unlawful; immigrant advocacy groups are seeking to block the agreement in Centro de Trabajadores Unidos v. Bessent. In February, news reports suggested 700,000 people would be targeted via this data sharing; more recently, the figure has risen to as many as 7 million people. This latter figure, the NYU Tax Law Center has noted, is far higher than the number of immigrants currently facing final deportation orders and is particularly concerning given the illegal deportations that have already occurred under the Trump administration. The signing of the MOU provoked the resignation of acting IRS Commissioner Melanie Krause, the third commissioner to resign since January.

This and other high-level departures linked to the Trump administration’s data-sharing demands indicate the seriousness of the privacy issues involved. They also mean that the implementation of the MOU will likely not receive appropriate levels of oversight. Asked recently about whether the memorandum is in compliance with IRS disclosure rules, former Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson said, “In my opinion, it’s not. And I think that’s what’s led to many people resigning, including, let me note, the chief counsel expert on 6103, which means your bulwark is gone.”

Politicization and the Erosion of IRS Independence

As the Trump administration continues to erode the IRS’s independent and nonpartisan civil service, the agency has also begun a process of politicization that will give more control of tax administration to political appointees and open the door to abuse of the tax system for political ends.

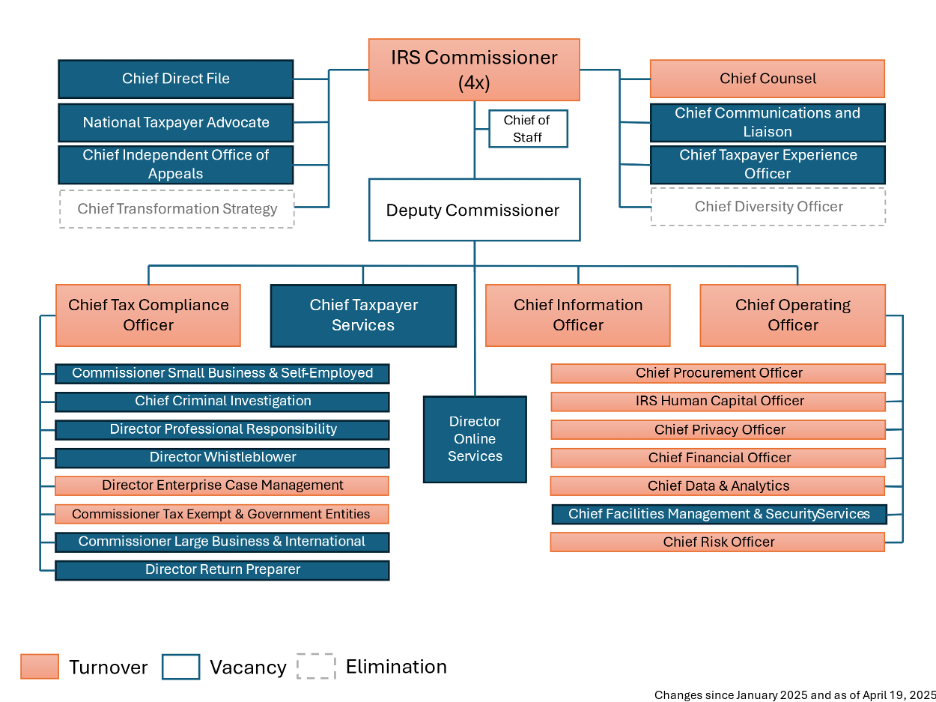

Figure 1 summarizes the loss of agency leadership between Jan. 20 and April 19. Of the 18 senior leadership positions that have seen turnover, only two—the IRS commissioner and the chief counsel—are Senate-confirmed political appointees. The IRS commissioner has a five-year appointment—a number intentionally greater than a single White House term in order to reinforce a culture of nonpartisanship. This year, however, IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel resigned on Jan. 20, the day the Biden administration ended. In the following weeks, two consecutive acting IRS commissioners resigned. Other departures include the chief risk officer, the chief privacy officer, the chief financial officer, and the chief information officer. (The head of the Direct File program remains on the IRS organizational chart, but news reports after Tax Day suggest that this well-regarded initiative to provide free, public tax preparation will be shut down.)

In addition to the resignations over privacy issues, there were also high-level departures over the firing of probationary workers. The IRS human capital officer attested that she was placed on leave over the concerns she raised. Joseph Rillotta, counselor to the IRS commissioner, characterized the government’s claim that firings were due to employees’ performance as “anticipatory fraud,” and then resigned.

Figure 1. Recent changes in IRS leadership.

The fourth person to hold the IRS commissioner position this year was Gary Shapley. Shapley, until recently a mid-level IRS agent, does not have the typical qualifications for IRS commissioner but had received praise in conservative media circles for his 2023 testimony that Hunter Biden’s tax case was being slow-walked by the agency. Before being made acting IRS commissioner, Shapley had already been promoted to deputy chief of the IRS’s criminal investigations and to a new advisory role at Treasury, connecting the department’s top political appointees directly to tax investigations.

Within days of his appointment as acting IRS commissioner, however, President Trump removed Shapley, an apparent casualty of conflict between Treasury Secretary Bessent and Elon Musk. The acting IRS commissioner is now Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Michael Faulkender, who served in the first Trump administration and as chief economist for the Trump-aligned America First Policy Institute.

The trend is clear: the decline of independent civil service and the rise of partisan loyalism at the top of the tax agency. Increasing the political control of the IRS was an explicit goal of the Heritage Foundation’s presidential transition playbook known as “Project 2025,” which called for a drastic increase in presidential appointees at the IRS, including appointees “not subject to Senate confirmation.” The politicization of the tax agency will likely accelerate with the recent revival of “Schedule F,” a regulatory change first proposed at the end of the first Trump administration that would remove civil service protections from about 50,000 federal employees. As political scientist Don Moynihan has noted, politicization of the civil service encourages corruption and extremism in government.

Remaining career staff may also be under new pressure for ideological conformity. The American Accountability Foundation, a small conservative outlet associated with the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, sent a dossier to Treasury Secretary Bessent purporting to show, based on their registration as Democrats, campaign contributions, or social media presence, the liberal leanings of certain high-level career IRS officials. One public servant, for example, was deemed to have “seemingly knocked President Trump” by reposting a 2020 election night tweet from actor George Takei that refers to “the spirits of John Lewis, Ruth Bader Ginsberg and John McCain.”

Greater control over the IRS will likely make it easier for President Trump to bring tax enforcement to bear on those perceived as enemies, an aspiration in his first term. The Trump administration is now trying to revoke the tax-exempt status of Harvard after the university refused to accede to demands for control over curriculum, hiring, and admissions. Harvard may be the front line of a broader challenge to the tax-exempt status of nonprofits disfavored by the administration—an effort reportedly led by Shapley and acting chief counsel Andrew De Mello, who was promoted after the previous counsel raised objections to DOGE’s data handling and was removed.

At least one example has already come to light of potential political interference in an ongoing tax enforcement case. This March, a Trump official wrote to the IRS asking about whether “a high-profile friend of the President” (Mike Lindell, the CEO of MyPillow) had been “inappropriately targeted” for an audit.

To obstruct an IRS officer’s work is, as one might imagine, illegal. There are also explicit prohibitions on interference with tax investigations by the president and many executive branch officials—a reform instituted after the revelations of the Nixon tapes, in which the president can be heard listing his criteria for a new tax commissioner:

I want to be sure he is a ruthless son of a b----, that he will do what he’s told, that every income tax return I want to see I see, that he will go after our enemies and not go after our friends.

Nixon’s efforts to pressure the IRS featured prominently in the case for his impeachment. The articles adopted by the House Judiciary Committee in July 1974 refer to both seeking “confidential information contained in income tax returns for purposes not authorized by law” and causing “income tax audits or other income tax investigations to be initiated or conducted in a discriminatory manner.”

The Trump administration’s actions are, as former IRS Commissioner John Koskinen has said, “moving back toward the Nixon ‘enemies list’.” They are also a move toward the kind of tax enforcement found in contemporary autocratic regimes like Hungary and Turkey: intended to chill dissent and undermine opposition. Those audits do not need to find wrongdoing to be successful. “It’s more about keeping us busy rather than shutting us down,” as one Hungarian anti-corruption activist put it.

Tax Capacity and Democracy

Taken together, the Trump administration’s attacks on the IRS will likely cost the United States hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars. As seven former IRS commissioners wrote in a joint op-ed in the New York Times in late February, slashing the IRS is like taking “an ax to accounts receivable, the part of an organization responsible for collecting revenue.” An estimate from the Yale Budget Lab finds that, if the most extreme of the proposed workforce cuts go through, “net forgone revenue could rise by $2.4 trillion over 10 years.”

Estimates of revenue loss from the workforce cuts are probably a floor rather than a ceiling. Americans have traditionally had exceptionally high “tax morale” by international standards: Despite our annual grumbling, there is a strong and long-standing popular commitment in the United States to the civic responsibility of taxpaying. But if it becomes clear that taxpaying by the wealthy has become functionally optional, it will erode mass tax compliance. The widespread perception (or reality) that taxpayers’ data is being misused could also do untold damage. These effects are unlikely to be linear, but it is very difficult to predict the tipping point from a norm of compliance to a norm of evasion.

The revenue raised by the IRS is a prerequisite for all federal action. For all Trump’s bluster about an “External Revenue Service,” tariffs simply cannot raise enough revenue to replace internal taxation. In fact, the unstable tariff regime currently being imposed is raising borrowing costs, making more expensive the debt upon which federal spending has long relied. Thus the damage being done to the IRS this year represents a de facto cut to the entire federal government. As the British statesman Edmund Burke once said, the “revenue of the state is the state.”

And this might seem to be a puzzle. As the Trump administration moves to consolidate its power, why would it undermine the agency that funds its endeavors?

If we look at the longer scope of American history, the co-occurrence of democratic erosion and a decline in tax capacity comes as no surprise at all. The people who have sought to undermine the U.S. government’s fiscal capacity have consistently been America’s anti-democratic forces. Like the three-fifths clause that distorted representation, the tax limitations in the U.S. Constitution were intended to protect slavery. Slaveholders feared that even a government chosen only by propertied white men might use the tax power to bring about abolition. Similarly, the Jim Crow governments of the American South developed supermajority requirements to prevent the taxation of property, a policy that worked hand in hand with voter suppression: Even if the biracial working-class majority somehow regained power, they would still not be able to tax the rich. Undermining tax administration is a standard component of reactionary politics in America.

Why? Taxation and representation are not just linked in a slogan; they develop together. When people see their government as legitimate and have a say in how public money is raised and spent, they are more willing to contribute. The need for tax revenue also encourages governments to be responsive to the citizenry. Thus the highest-tax countries in the world also rank at the top of global democracy indices. Autocracies have less effective tax regimes, in part because their residents have lower tax morale. But autocrats also do not want an effective tax system, because taxation provokes demands for representation. They prefer to rely on tributes, and on the fees and fines they can extract from a corrupted justice system.

It is too early to judge how, or whether, the United States will reverse its current autocratic trajectory. But we should recognize that the lurch toward a personalist, strongman government is reinforced by the destruction of an independent civil service, and particularly the destruction of the independent, nonpartisan tax service.

.png?sfvrsn=48e6afb0_5)