Avoiding Post-Election Chaos: Wilson vs. Hughes, 1916

President Trump’s recent refusals to commit to a peaceful transfer of power have called to mind historical contrasts.

The prospect of a contested presidential election, including premature claims of victory—or worse, one in which President Trump deliberately foils a clear outcome against him—rightly has people worried. It’s a reminder that some structural aspects of the U.S. presidential election system, like its decentralization and long transition period between election and inauguration, can be major liabilities. It’s also a reminder of how much the system depends on candidates’ commitment to certain principles and to the system itself.

Trump’s recent behavior and rhetoric have called to mind historical contrasts. A few weeks ago, for example, his talk of postponing the election drew attention to the 1864 election—held on time amidst the Civil War—and to President Lincoln’s “Blind Memorandum.” Lincoln expected he might lose that most critical election, and six weeks before the vote, he described in a sealed document the momentous obligations before him:

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards. — A. Lincoln

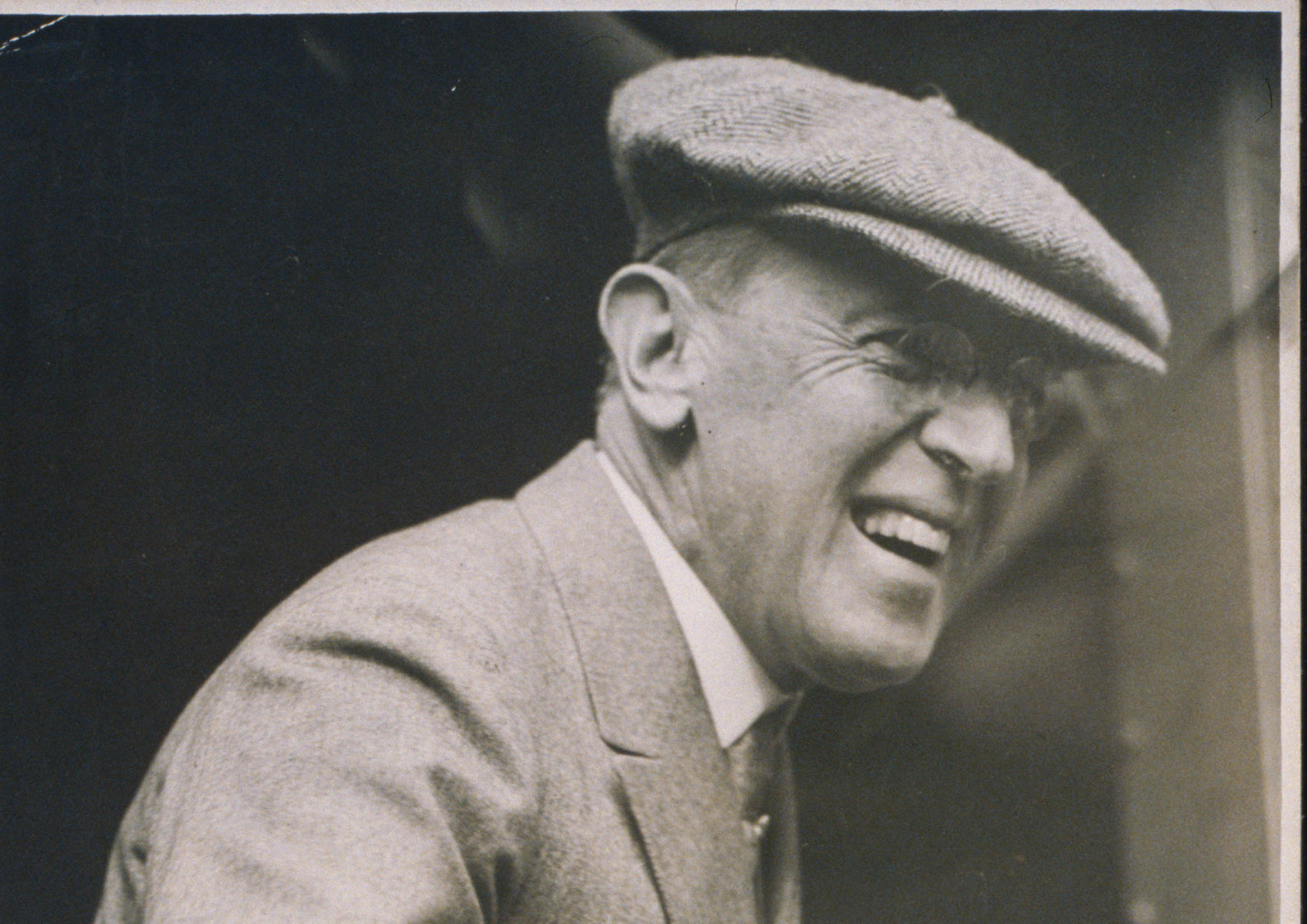

The statesmanship of the 1916 election likewise offers a remarkable contrast to where the country is today—and is also a vivid reminder of transition period perils. The 1916 election pitted incumbent Democrat Woodrow Wilson against Republican Charles Evans Hughes, who had stepped down from the Supreme Court to run.

That election occurred at a dire moment for American national defense, when the vortex of Europe’s great war threatened to pull in a poorly prepared United States. Yet both candidates displayed a willingness to work with their opponent for the good of the country under potentially dangerous circumstances.

Election Day, Nov. 7, 1916, looked like a Hughes win. Early returns on Tuesday were breaking his way. Hughes biographer Merlo J. Pusey describes the scene that night: “As the [Hughes] family ate dinner, friends repeatedly burst into their suite to overwhelm them with good news, and an avalanche of favorable bulletins descended upon their table. The World and several other New York newspapers conceded Hughes’s election. Reporters begged for a statement …. Times Square flashed the news of a great Hughes victory to a crowd estimated at a hundred thousand.” Supporters and some advisers pleaded with Hughes to declare victory.

Hughes, ever cautious, replied: “If I have been elected President, it is because the people of this country think that I’ll keep my shirt on in an emergency. I’ll start right now by not yielding to this demand when I am not positive that I have been elected.” Hughes took nothing for granted, and he would have regarded election-night political gamesmanship as beneath the presidential office.

Hughes, of course, was right to be cautious, but he wouldn’t know just how right for several days. Slowly, over the course of that week, returns increasingly pointed toward Wilson’s reelection. It was not until that Friday that enough tallies came in from rural California to suggest that Wilson had won the state—and therefore the Electoral College victory. (Ultimately, when the ballots were fully counted, Wilson won that key state by fewer than 4,000 votes.)

Some Republican officials smelled something foul and started alleging possible fraud. Hughes would not have it, and he shut down those rumors. “Hughes Silences Hasty Fraud Cry” ran the page-one headline in Saturday’s New York Times, which reported: “Mr. Hughes declared that in the absence of absolute proof of fraud no such cry should be raised to becloud the title of the next President of the United States.” That is a line that the current Republican leadership should embrace.

The 1916 election took a long time to sort out, at a perilous moment for the United States. By Nov. 22, enough counts were finally completed and checked that Hughes telegrammed Wilson a gracious concession.

There’s no way to know for sure whether Wilson would have followed through, but if Hughes had won, Wilson planned for a stunning move. He took steps to possibly hand off the presidency early, fearing that a long transition period before Inauguration Day—which at the time was in early March—would be too dangerous given the precariousness of American war diplomacy.

In his early life as a scholar, Wilson had written about the structural defects of the U.S. constitutional system for managing crises. So it should be no surprise that he thought about them as president. What is surprising are the actions he planned. Assuming that they went along with this move, in the interim between Hughes’s election and inauguration, Wilson would appoint Hughes to replace Robert Lansing as his secretary of state. Once Hughes was in that office, Wilson and Vice President Thomas Marshall would resign, whereupon, according to succession rules at the time, Hughes would become president early.

Lansing revealed the plan in his memoirs two decades later. Thanks to Wilson historian Arthur Link, the letter Wilson wrote to Lansing, dated and wax-sealed two days before the election, is available here. In it, Wilson laid out the dilemma as he saw it:

Again and again the question has arisen in my mind, What would it be my duty to do were Mr. Hughes to be elected? Four months would elapse before he could take charge of the affairs of the government, and during those four months I would be without such moral backing from the nation as would be necessary to steady and control our relations with other governments. I would be known to be the rejected, not the accredited, spokesman of the country; and yet the accredited spokesman would be without legal authority to speak for the nation. Such a situation would be fraught with the gravest dangers.

After explaining the plan to hand over the presidential reins early, Wilson further explained why current foreign policy circumstances made it necessary:

All my life long I have advocated some such responsible government for the United States as other constitutional systems afford as of course, and as such action on my part would inaugurate, at least by example. … Here is the remedy, at any rate so far as the Executive is concerned. In ordinary times it would perhaps not be necessary to apply it. But it seems to me that in the existing circumstances it would be imperatively necessary. The choice of policy in respect of our foreign relations rests with the Executive. No such critical circumstances in regard to our foreign policy have ever before existed.

Wilson therefore concluded: “It would be my duty to step aside so that there would be no doubt in any quarter how that policy was to be directed, towards what objects and by what means. I would have no right to risk the peace of the nation by remaining in office after I had lost my authority.”

It’s impossible to say how Hughes would have responded to this plan. Most Wilson biographies discuss the episode, and Wilson’s election-night expectations of a loss, only in passing—though biographer Scott Berg concludes that Wilson “fully intended to act upon it, if necessary.” I have my doubts, and I think Wilson greatly overstates the risks and claims of necessity. But the mere possibility of the move and Wilson’s logic are astonishing. (Perhaps weird things happen when the U.S. elects a professor-president.)

In 1916, the general dilemma of lame-duck foreign policy was getting worse, as the United States took on a greater place in the world and 20th-century technology accelerated the pace of diplomacy. Those trends continued steeply. The 20th Amendment, added in the early 1930s, mitigated them somewhat by moving up inauguration to January and thus shortening the transition period. But the United States still has an abnormally long leadership transition compared to other major democracies. Plans like Wilson’s seem inconceivable today.

So what is the patch for this constitutional bug? Statutes like the Logan Act and the Presidential Transition Act are of limited help. The U.S. has amended the Constitution’s timing and structure for presidential transitions before, and Americans could do so again. Barring a catastrophe, though, that is implausible anytime soon.

In the absence of legal fixes, mitigating problems of messy transitions and averting disastrous foreign policy hand-offs requires candidates’ commitment to certain principles. One is genuinely close cooperation between the outgoing and incoming national security teams, including assistance and vital information from the outgoing to the incoming one. Another is the one-president-at-a-time ethic. A third is balancing legacy-building with avoiding lurches; it is one thing to try to lock in policies and another to create new crises. In a recent essay, Tim Naftali writes that modern-era presidential transitions have hit many foreign policy snags when these principles are not abided, especially as outgoing incumbents pursue last-chance moves and presidents-elect seek an early start.

Should Biden win the election, the current political rancor will make this transition more difficult than any past such periods I can think of. Based on what I have seen from President Trump so far, I have grave doubts that he will provide needed leadership on the first principle or abide by the third.