Gabriella Blum on Spiders and "Invisible Threats"

Gabriella Blum has a new essay out entitled, "Invisible Threats." Part of the Emerging Threats series of the Hoover Institution's Koret-Taube Task Force on National Security and Law (of which Jack, Ken, Matt, and I am are all member), the paper is actually part of a larger project Gabby and I are working on involving technology proliferation, security, and privacy.

Gabriella Blum has a new essay out entitled, "Invisible Threats." Part of the Emerging Threats series of the Hoover Institution's Koret-Taube Task Force on National Security and Law (of which Jack, Ken, Matt, and I am are all member), the paper is actually part of a larger project Gabby and I are working on involving technology proliferation, security, and privacy. It might be a little self-serving for me to recommend it highly, but I nonetheless recommend it highly. It opens with creepy aplomb:

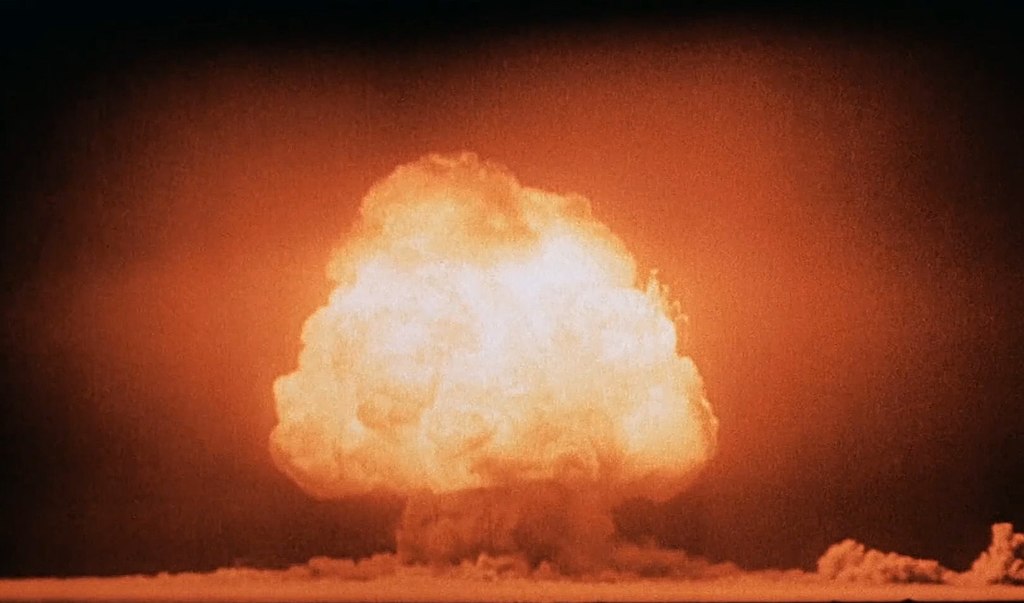

You walk into your shower and find a spider. You are not an arachnologist. You do, however, know that any one of the four following options is possible: a. The spider is real and harmless. b. The spider is real and venomous. c. Your next-door neighbor, who dislikes your noisy dog, has turned her personal surveillance spider (purchased from “Drones ‘R Us” for $49.95) loose and is monitoring it on her iPhone from her seat at a sports bar downtown. The pictures of you, undressed, are now being relayed on several screens during the break of an NFL game, to the mirth of the entire neighborhood. d. Your business competitor has sent his drone assassin spider, which he purchased from a bankrupt military contractor, to take you out. Upon spotting you with its sensors, and before you have any time to weigh your options, the spider shoots an infinitesimal needle into a vein in your left leg and takes a blood sample. As you beat a retreat out of the shower, your blood sample is being run on your competitor’s smartphone for a DNA match. The match is made against a DNA sample of you that is already on file at EVER.com (Everything about Everybody), an international DNA database (with access available for $179.99). Once the match is confirmed (a matter of seconds), the assassin spider outruns you with incredible speed into your bedroom, pausing only long enough to dart another needle, this time containing a lethal dose of a synthetically produced, undetectable poison, into your bloodstream. Your assassin, who is on a summer vacation in Provence, then withdraws his spider under the crack of your bedroom door and out of the house and presses its self-destruct button. No trace of the spider or the poison it carried will ever be found by law enforcement authorities. This is the future. According to some uncertain estimates, insect-sized drones will become operational by 2030. These drones will be able to not only conduct surveillance, but to act on it with lethal effect. Over time, it is likely that miniaturized weapons platforms will evolve to be able to carry not merely the quantum of lethal material needed to execute individuals, but also weapons of mass destruction sufficient to kill thousands. Political scientist James Fearon has even speculated that at some more distant point in time, individuals will be able to carry something akin to a nuclear device in their pockets. Assessing the full potential of technology as it expands (and shrinks) requires a scientific expertise beyond my ken. The spider in the shower is merely an inkling of what probably lies in store. But even a cursory glance at ongoing projects tells us that the mind-bending speed at which robotics and nanobotics are developing means that a whole range of weapons is growing smaller, cheaper, and easier to produce, operate, and deploy from great distances. If the mis-en-scene above seems unduly alarmist or too futuristic, consider the following: Drones the size of a cereal box are already widely available, can be controlled by an untrained user with an iPhone, cost roughly $300, and come equipped with cameras. Palm-sized drones are commercially available as toys (such as the Hexbug), although they are not quite insect-sized and their sensory input is limited to primitive perception of light and sound. True minidrones are still in the developmental stages, but the technology is progressing quickly. The technological challenges seem to be not in making the minidrones fly, but in making them do so for long periods of time while also carrying some payload (surveillance or lethal capacity). The flagship effort in this area appears to be the Micro Autonomous Systems and Technology (MAST) Collaborative Technological Alliance, which is funded by the U.S. Army and led by BAE Systems and U.C. Berkeley, among others. The Alliance’s most recent creations are the Octoroach and the BOLT (Bipedal Ornithopter for Locomotion Transitioning). The Octoroach is an extremely small robot with a camera and radio transmitter that can cover up to 100 meters on the ground, and the BOLT is a winged robot designed to increase speed and range on the ground. Scientists at Cornell University, meanwhile, recently developed a hand-sized drone that uses flapping wings to hover in flight, although its stability is still quite limited and battery weight remains a problem. A highly significant element of the Cornell effort, however, is that the wing components were made with a 3-D printer. This heralds a not-too-distant future in which a person at home can simply download the design of a drone, print many of the component parts, assemble them with a camera, transmitter, battery, etc., and build themselves a fully functioning, insect-sized surveillance drone. Crawling minidrones have clearly passed the feasibility threshold and merely await improvements in range and speed to attain utility on the battlefield and viability in the private sector. Swarms of minidrones are also being developed to operate with a unified goal in diffuse command and control structures. Robotics researchers at the University of Pennsylvania recently released a video of what they call “nano quadrotors”—flying mini-helicopter robots that engage in complex movements and pattern formation. A still more futuristic technology is that of nanobots or nanodrones. The technology for manufacturing microscopic robots has been around for a few years, but recent research has advanced to the point of microscopic robots that can assemble themselves and even perform basic tasks. The robotics industry, both governmental and private, is also exerting great efforts to enhance the autonomous capabilities of robots, that is, to be able to program a robot to perform complex tasks with only a few initial commands and no continuous control. Human testing for a microrobot that can be injected into the eye to perform certain surgical tasks is now on the horizon. Similar developments have been made toward nanobots that will clear blocked arteries and perform other procedures. Now, situate the robotics technology alongside other technological and scientific advancements—the Internet, telecommunications, and biological engineering—all of which empower individuals to do both good and terrible things to others. From here, it is not hard to conceptualize a world rife with miniature, possibly molecule-sized, means of inflicting harm on others, from great distances and under clandestine conditions. When invisible remote weapons become ubiquitous, neither national boundaries nor the lock on our front door will guarantee us an effective line of defense. As the means to inflict violence from afar become more widely available, both individual threat and individual vulnerability increase to a hitherto unknown degree. When the risk of being detected or held accountable diminishes, inhibitions regarding violence decrease. Whether political or criminal, violence of every kind becomes easier to inflict and harder to prevent or account for. Ultimately, modern technology makes individuals at once vulnerable and threatening to all other individuals to unprecedented degrees: we are all vulnerable—and all menacing. In this essay I take on some of the possible ramifications of these technological advances for the potential incidence of violence and its future effects on the existing legal and political order. I first consider the special features of new weapons technologies that, in my mind, are likely to make violence more possible and more attractive; these are proliferation, remoteness, and concealment. All in all, I argue that technology has found a way to create “perfect weapons”—altogether distant, invisible, and untraceable, essentially generating a more leveled playing field among individuals, groups, and states. I then reflect on the implications of this development for the traditional legal and political categories—national and international, private and public, citizen and alien, war and crime—that still serve as the basis for much of existing regulation of violence, and argue that these juxtapositions are becoming increasingly vague and inapplicable as rationales for regulation of new threats. Finally, I venture to imagine some broader themes of the future defense against the threat of new weapons, both on the international level (a move to global policing) and on the domestic level (privatization of defense). I argue that as threats increasingly ignore conventional boundaries or nationalities and become more individualized, the traditional division of labor between government and citizens and between domestic and international becomes impractical. National defense will require a different mix of unilateralism and international cooperation. Personal defense will have to rely more on diffuse, private, person-to-person mechanisms of protection, as well as concede more power to the government. The very concept of state sovereignty—what it means domestically and what it means externally—would have to be reimagined, given the new strategic environment.The paper joins earlier contributions in the series from Shane Harris, Paul Rosenzweig, and Jeremy and Ariel Rabkin.

Benjamin Wittes is editor in chief of Lawfare and a Senior Fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution. He is the author of several books.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=7aa9b087_9)

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)